Traditional Rights and Freedoms— Encroachments by Commonwealth Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Analysis of the Law Surrounding 'One Punch' Killings

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS Critical analysis of the law surrounding "one punch" killings Burgess, Craig Award date: 2016 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE LAW SURROUNDING ‘ONE PUNCH’ KILLINGS AUGUST 1, 2016 CRAIG NEILSON BURGESS Abstract This thesis investigates the modern day tragedy of needless loss of life through so-called ‘one punch’ killings. Research has identified more than 90 deaths attributed to so-called ‘one punch’ assaults in Australia between 2000 and 2012. This thesis takes a critical examination of recent legislative moves in Australia and in some overseas jurisdictions that tighten the liability of offenders and the trend of concentrating on the consequences of the crime rather than looking towards the criminality of the offender. It also examines the efficacy of introducing new offences that abolish the test of foresight regarding the outcome of a fatal assault, in order to deal with the problem of mainly alcohol-fuelled violence. The thesis then considers whether there is a justifiable reason to amend the law and whether or not the range of existing offences which already carry high maxima, more fairly and justly labels the crime for the benefit of the offender, the victim and the community. -

Crimes Legislation Amendment (Economic Disruption) Bill 2020

Crimes Legislation Amendment (Economic Disruption) Bill 2020 Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee 16 October 2020 Telephone +61 2 6246 3788 • Fax +61 2 6248 0639 Email [email protected] GPO Box 1989, Canberra ACT 2601, DX 5719 Canberra 19 Torrens St Braddon ACT 2612 Law Council of Australia Limited ABN 85 005 260 622 www.lawcouncil.asn.au Table of Contents About the Law Council of Australia ............................................................................... 3 Acknowledgement .......................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 5 Overview of proposed amendments.............................................................................. 6 Money laundering offences (Schedule 1) ...................................................................... 6 New ‘tiers’ of offences for high-value money laundering............................................. 6 Proof of predicate offences ........................................................................................ 6 Fault elements for attempt offences in relation to Division 400 ................................... 8 Definition of ‘deals with’ in relation to money or property ............................................ 8 Partial defence of ‘mistake of fact as to value’ ........................................................... 9 Obligations in covert investigations (Schedule -

Macquarie a Smart Investment

Macquarie a smart investment Macquarie is Australia’s best modern university, so you’ll graduate with an internationally respected degree We adopt a real-world approach to learning, so our graduates are highly sought-after. CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for graduate recruitment Our campus is surrounded by leading multinational companies, giving you unparalleled access to internships and greater exposure to the Australian job market You will love the park-like campus for quiet study or catching up with friends among the lush green surrounds Investments of more than AU$1 billion in facilities and infrastructure ensure you have access to the best technology and facilities Our friendly, welcoming campus community is home to students from over 100 countries 2 MacquarIE UNIVERSIty Contents FACULTY OF ARTS 5 Media and creative arts 6 Security and intelligence 8 Society, history and culture 10 Macquarie Law School 14 FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND EcoNOMIcs 17 Business 18 MACQUARIE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 22 FACULTY OF HumaN SCIENCEs 23 Education and teaching 24 Health sciences 29 Linguistics, translating and interpreting 32 Psychology 35 MEDICINE AND SURGERY 38 FACULTY OF SCIENCE 39 Engineering and information technology 40 Environment 42 Science 47 Higher degree research at Macquarie 50 How to apply: your future starts here 52 English language requirements 54 This is just the beginning: discover more 55 This document has been prepared by the The University reserves the right to vary Marketing Unit, Macquarie University. The or withdraw any general information; any information in this document is correct at course(s) and/or unit(s); its fees and/or time of publication (July 2013) but may the mode or time of offering its course(s) no longer be current at the time you refer and unit(s) without notice. -

Final Submission to the NSW Law Reform Commission's Review Of

Final Submission to the NSW Law Reform Commission’s Review of Consent and Knowledge of Consent in Relation to Sexual Assault Offences Andrew Dyer* 1 February 2019 Introduction 1. In this submission, I respond to most of the questions posed by the New South Wales Law Reform Commission (NSWLRC) in its recent Consultation Paper1 regarding s 61HA of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) and related issues. It must be noted immediately, however, that on 1 December 2018 the Criminal Legislation Amendment (Child Sexual Abuse) Act 2018 came into force. This means that s 61HA no longer deals with consent and knowledge of non-consent for the purposes of the sexual assault offences for which the Crimes Act provides. Because s 61HE now regulates such matters (indeed, as the Consultation Paper notes,2 s 61HE applies also to the new sexual touching and sexual act offences created by ss 61KC, 61KD, 61KE and 61KF of the Act), I will refer in this submission to the terms of this new section when making recommendations for reform. 2. Consistently with the views that I expressed in my preliminary submission to this Review, no radical changes should be made to s 61HE.3 However, after reading the Consultation Paper and many of the preliminary submissions, and after considering the terms of the new section, I do accept that it is desirable to make certain alterations to that section in addition to the one that I advocated in my initial submission.4 It is possible that few of the changes to s 61HE that I argue for here would alter the law in this area; however, in my submission, they would clarify the scope of s 61HE – and the manner in which it operates. -

High Court of Australia

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA GLEESON CJ, GUMMOW, KIRBY, HAYNE, HEYDON, CRENNAN AND KIEFEL JJ THE QUEEN APPELLANT AND WEI TANG RESPONDENT The Queen v Tang [2008] HCA 39 28 August 2008 M5/2008 ORDER 1. Appeal allowed. 2. Special leave to cross-appeal on the first and second grounds in the proposed notice of cross-appeal granted. Cross-appeal on those grounds treated as instituted, heard instanter, and dismissed. 3. Special leave to cross-appeal on the third ground in the proposed notice of cross-appeal refused. 4. Set aside orders 3, 4 and 5 of the orders of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria made on 29 June 2007 and, in their place, order that the appeal to that Court against conviction be dismissed. 5. The appellant to pay the respondent's costs of the application for special leave to appeal and of the appeal to this Court. 6. Remit the matter to the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria for that Court's consideration of the application for leave to appeal against sentence. On appeal from the Supreme Court of Victoria 2. Representation W J Abraham QC with R R Davis for the appellant (instructed by Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth)) N J Young QC with M J Croucher and K L Walker for the respondent (instructed by Slades & Parsons Solicitors) Interveners D M J Bennett QC, Solicitor-General of the Commonwealth with S P Donaghue intervening on behalf of the Attorney-General of the Commonwealth (instructed by Australian Government Solicitor) B W Walker SC with R Graycar intervening on behalf of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (instructed by Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission) Notice: This copy of the Court's Reasons for Judgment is subject to formal revision prior to publication in the Commonwealth Law Reports. -

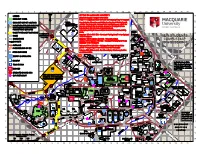

Campus Map New Students 2016 Session 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 A A B B C C D D NEW STUDENTS E CAMPUS MAP E 2016 SESSION 1 F F G G H H J J BIKE K HUB K L L BIKE HUB M M N N O O P BIKE P HUB Q Q R R S S T T U U V V W W 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 LOCATION GUIDE Telephone Switchboard: +61 2 9850 7111 General Email: [email protected] Web Site: mq.edu.au LOCATION BUILDING REF Cognitive Science S2.6 T14 ART GALLERY & MUSEUMS Graduation Unit C8A L3 N18 Emergency & First C1A S17 Institute of Early Childhood X5B L3 N10 Art Gallery E11A L1 H20 Higher Degree Research C5C L3 O17 Aid 9850 9999 Office Linguistics C5A L5 P16 Australian History Museum W6A 126 O12 Security & C1A S17 Hospital & Allied Health F8A L27 Psychology C3A L5 Q16 Biological Sciences Museum E8B L23 services Information Learning & Teaching Centre C3B P17 Student Connect C7A N15 School of Education C3A L8 Q16 Herbarium E8C L1 M23 Library C3C Q17 Macquarie E-Learning W6B 152 N12 IEC Art Collection X5B N10 Centre of Excellence Macquarie International E3A Q20 FACULTY OF ARTS W6A L1 O12 Lachlan Macquarie Room C3C Q17 Macquarie ICT C5B L0 O16 Arts Student Centre W6A L1 O12 Medical Centre & Clinic F10A L3 K26 Innovations Centre Museum of Ancient Cultures X5B 331 N10 Macquarie University X5A O9 METS (Macquarie F9B K24 Sporting Hall of Fame W10A J12 Engineering Technical Ancient History W6A 540 O12 Special Education Museum Services) Anthropology W6A 615 O12 MUSRA C10A L1 K17 FACULTY OF MEDICINE & HEALTH SCIENCES English -

Undergraduate Courses2020

Undergraduate courses 2020 When your potential is multiplied by a university built for collaboration, anything can be achieved. That’s YOU to the power of us At Macquarie, we have discovered the human equation for success. By knocking down the walls between departments, and uniting the powerhouses of research and industry, human collaboration can flourish. This is the exponential power of our collective, where potential is multiplied by a campus and curriculum designed to foster collaboration for the benefit of everyone. Because we believe when we all work together, we multiply our ability to achieve remarkable things. That’s YOU to the power of us 4 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 5 Contents MACQUARIE AT A GLANCE 6 MAKE YOUR DREAM CAREER A REALITY 10 PACE (PROFESSIONAL AND 12 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT) GLOBAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAM 14 STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAM 16 GLOBAL LEADERS ON THE DOORSTEP 20 OUR CAMPUS 22 SUPPORT, SERVICES AND FLEXIBILITY 24 STUDENT ACCOMMODATION 26 MACQUARIE ENTRY 30 ADJUSTMENT FACTORS 32 CASH IN WITH A SCHOLARSHIP 34 WHAT CAN I STUDY? 36 FEES AND OTHER COSTS 40 HOW TO APPLY 41 LEARN THE LINGO 42 COURSES MADE BY (YOU)us 44 2019 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 106 Questions? Ask us anything … FUTURE STUDENTS Degrees, entry requirements, fees and general enquiries: • chat live by clicking on the chat icon on any degree page • ask us a question at [email protected] • call us on (02) 9850 6767. 6 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 3 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 3 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Macquarie University at a Glance

Macquarie University at a glance CRICOS Number 00002J Macquarie at a glance • Established in 1964 • 1300 academic staff • 39,600 students • 9,000 international students • Top 2 per cent of universities globally • 156,000 alumni in more than 140 countries • Among the top 10 universities in Australia • Among the top 40 universities in Asia-Pacific CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for their graduate recruitment 2012 Global Employability Survey CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for their graduate recruitment 2012 Global Employability Survey Located 15 kms from the Sydney CBD Located 15 kms from the Sydney CBD Sydney is one of the 10 best cities in the world to live in The Economist Global Liveability Report, 2012 Living in Sydney MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY Find out why Enjoy Sydney’s the koalas and fantastic kangaroos at shopping, some Taronga Zoo of which is located have some right next to the of the most University in the amazing views Macquarie Centre in the world shopping complex Take a day trip Relax and to the world unwind on one heritage listed of Sydney’s Blue Mountains, 100 beaches, only 90 minutes including the away from world-famous Macquarie Bondi Beach Rankings and ratings MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY • has 5 QS stars in teaching, employability, research, internationalisation, facilities, innovation, access and specialist subjects • is ranked in the top 2% of universities globally • is among the top 10 universities in Australia • is among the top 40 universities in Asia-Pacific -

The Comparative Distinctiveness of Equity

(2016) 2(2) CJCCL 403 The Comparative Distinctiveness of Equity Justice Mark Leeming Judge of Appeal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales* 2016 CanLIIDocs 51 Comparative law is difficult and controversial. One reason for the difficulty is the complexity of legal systems and the need for more than a merely superficial knowledge of the foreign legal system in order to profit from recourse to it. One way in which it is controversial is that it has been suggested that the use of comparative law conceals the reasons for decisions reached on other grounds. This paper maintains that equity is distinctive, and that one of the ways in which equity is different from other bodies of law is that there is greater scope for the development of equitable principle by reference to foreign jurisdictions. That difference is a product of equity’s distinctive history, underlying themes and approach to law-making. Those matters are illustrated by a series of recent examples drawn from appellate courts throughout the Commonwealth. * I am grateful for the assistance provided by Kate Lindeman and Hannah Vieira in the preparation of this article. All errors are mine. 404 Leeming, The Comparative Distinctiveness of Equity I. Introduction II. The Problem of Generality III. The Use of Foreign Equity Decisions IV. The Variegated Common Law of the Commonwealth V. Three Examples of Equitable Principle in Ultimate Appellate Courts A. Barnes v Addy: Liability for Knowing Assistance in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom B. Qualifications to the Rule in Saunders v Vautier C. Judicial Advice 2016 CanLIIDocs 51 VI. -

Undergraduate Courses2022

Undergraduate courses 2022 When your potential is multiplied by a university built for collaboration, anything can be achieved. That’s YOU to the power of us 2 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2022 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2022 3 At Macquarie, we have discovered the human equation for success. By knocking down the walls between departments, and uniting the powerhouses of research and industry, human collaboration can flourish. This is the exponential power of our collective, where potential is multiplied by a campus and curriculum designed to foster collaboration for the benefit of everyone. Because we believe when we all work together, we multiply our ability to achieve remarkable things. That’s YOU to the power of us Why Macquarie? DEGREES CO-DESIGNED WITH INDUSTRY Many of our degrees are co-designed with industry. This means they’re shaped by the latest industry trends and adjusted to respond to the real-time needs of industry. DEGREES WITH IN-BUILT INTERNSHIPS Practical experience is built into all of our degrees. So when you graduate, you’ll have the knowledge and skills you’ll need to meet the current and future challenges of your chosen profession. PERSONALISED DEGREES All universities offer double degrees, but we let you personalise your double degree by choosing the combination you consider will best kick-start your career. CAREER AND EMPLOYMENT SERVICE We can help you prepare a résumé, identify job opportunities, and connect you with employers and industry partners through our unique recruitment service. MULTIMODE STUDY As a Macquarie student, you have the option to undertake your degree on campus or online – or a combination of both. -

5281 Bar News Winter 07.Indd

CONTENTS 2 Editor’s note 3 President’s column 5 Opinion The central role of the jury 7 Recent developments 12 Address 2007 Sir Maurice Byers Lecture 34 Features: Mediation and the Bar Effective representation at mediation Should the New South Wales Bar remain agnostic to mediation? Constructive mediation A mediation miscellany 66 Readers 01/2007 82 Obituaries Nicholas Gye 44 Practice 67 Muse Daniel Edmund Horton QC Observations on a fused profession: the Herbert Smith Advocacy Unit A paler shade of white Russell Francis Wilkins Some perspectives on US litigation Max Beerbohm’s Dulcedo Judiciorum 88 Bullfry Anything to disclose? 72 Personalia 90 Books 56 Legal history The Hon Justice Kenneth Handley AO Interpreting Statutes Supreme Court judges of the 1940s The Hon Justice John Bryson Principles of Federal Criminal Law State Constitutional Landmarks 62 Bar Art 77 Appointments The Hon Justice Ian Harrison 94 Bar sports 63 Great Bar Boat Race The Hon Justice Elizabeth Fullerton NSW v Queensland Bar Recent District Court appointments The Hon Justice David Hammerschlag 64 Bench and Bar Dinner 96 Coombs on Cuisine barTHE JOURNAL OF THEnews NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2007 Bar News Editorial Committee Design and production Contributions are welcome and Andrew Bell SC (editor) Weavers Design Group should be addressed to the editor, Keith Chapple SC www.weavers.com.au Andrew Bell SC Eleventh Floor Gregory Nell SC Advertising John Mancy Wentworth Selborne Chambers To advertise in Bar News visit Arthur Moses 180 Phillip Street, www.weavers.com.au/barnews Chris O’Donnell Sydney 2000. or contact John Weaver at Carol Webster DX 377 Sydney Weavers Design Group Richard Beasley at [email protected] or David Ash (c) 2007 New South Wales Bar Association phone (02) 9299 4444 Michael Kearney This work is copyright.