Evaluation of the American Automobile Labeling Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Police Department

Mobile Police Department Impound Yard Vehicle Auction 1251 Virginia Street, Lot B December 14, 2010 Registration @ 8:00am Bidding to start @ 9:00am All cars to be sold in "As is Condition" Cash, Credit Cards or Debit Cards Only! NO CHECKS Pre-registration available one week prior to auction. 1996 BUICK CENTURY 1G4AG55MXT6437476 1994 BUICK CENTURY 3G4AG55MXRS605587 1992 BUICK LESABRE 1G4HR53L4NH415130 1992 BUICK REGAL 2G4WB54L5N1447579 1992 BUICK REGAL CUS 2G4WB54T5N1467850 1993 BUICK PARK AVENUE 1G4CW53L7P1625865 1992 BUICK ROADMASTER 1G4BN5377NR449092 2000 CADILLAC DEVILLE 1G6KD54Y3YU293555 1995 CADILLAC DEVILLE 1G6KD52B3SU241252 1976 CADILLAC DEVILLE 6D49S6Q276445 1987 CHEVROLET ASTRO VAN 1GNDM15Z8HB117724 2000 CHEVROLET BLAZER 1GNCS13W8Y2311373 1995 CHEVROLET BLAZER 1GNDT13W5S2158105 1991 CHEVROLET CAPRICE 1G1BL53E1MR113860 1997 CHEVROLET CAVALIER 1G1JC1242VM134535 1994 CHEVROLET CAVALIER 1G1JC1446R7345352 1997 CHEVROLET GEO PRIZM 1Y1SK5268VZ453217 1984 CHEVROLET IMPALA 1G1AL69H8EX116920 1979 CHEVROLET MALIBU 1W35M9D515918 1996 CHEVROLET S10 1GCCS1442V8118800 1994 CHEVROLET S10 1GCCS19Z9R8223604 1994 CHEVROLET S10 4X2 1GCCS14Z9R8119962 1995 CHEVROLET VAN 1GCDG15HXSF128358 1997 CHRYSLER TOWN & CO 1C4GP64L6VB399042 1993 DODGE CARAVAN 2B4GH45R4PR339329 2000 FORD CROWN VIC 2FAFP71W6YX128036 1997 FORD CROWN VIC 2FALP73W0VX203888 1999 FORD ESCORT 1FAFP13P8XW200769 1997 FORD EXPLORER 1FMDU32E1VUA15991 1996 FORD EXPLORER 1FMCU22X2TUC75725 1996 FORD EXPLORER 1FMDU34X6TUA75020 1992 FORD EXPLORER 1FMDU32X1NUB26817 1995 FORD F150 1FTEX15N6SKB19593 -

North America Sales History and Forecast

North America sales history and forecast 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 U.S. car 131,559 153,658 162,703 172,505 166,848 170,794 172,594 195,026 211,172 Canada car 7,701 8,922 9,182 9,900 10,903 10,895 10,872 13,956 13,423 Mexico car 1,944 2,442 3,995 5,219 4,573 4,990 6,468 7,680 8,189 North America car 141,204 165,022 175,880 187,624 182,324 186,679 189,934 216,662 232,784 U.S. truck – 1,312 26,720 40,622 34,021 37,789 68,611 66,613 67,151 Canada. truck – 89 1,840 2,802 3,072 2,857 5,102 5,142 4,909 Mexico truck 115 233 213 897 982 989 928 890 983 North America truck 115 1,634 28,773 44,321 38,075 41,635 74,641 72,645 73,043 BMW 141,319 166,656 204,653 231,945 220,399 228,314 264,575 289,307 305,827 U.S. car 739,217 – – – – – – – – Canada car 86,148 – – – – – – – – Mexico car 47,176 – – – – – – – – North America car 872,541 – – – – – – – – U.S. truck 1,770,794 – – – – – – – – Canada truck 183,048 – – – – – – – – Mexico truck 45,123 – – – – – – – – North America truck 1,998,965 – – – – – – – – CHRYSLER CORP. 2,871,506 – – – – – – – – U.S. car – 889,506 894,219 863,043 739,430 744,526 751,850 775,084 796,545 Canada car – 92,064 89,163 76,691 83,291 80,243 79,625 84,883 88,430 Mexico car 52,058 65,957 86,948 78,504 86,942 87,746 91,957 97,751 North America car – 1,033,628 1,049,339 1,026,682 901,225 911,711 919,221 951,924 982,726 U.S. -

Automobile Industry: SUV Category

Name: Loveesh Bhatt MMS-Marketing , 20 Automobile Industry: SUV Category Leader : Mahindra and Mahindra M&M with their recent launches have made it to the number one position in the SUV category in Indian market. M&M have been very precise and accurate in understanding the customer’s needs and what customer wants from a SUV. Since its launch of Scorpio, M&M have been consistent in their sales record. M&M have been strong internationally as well. Mahindra & Mahindra is a major automobile manufacturer of utility vehicles, passenger cars, pickups, commercial vehicles, and two wheelers in various countries. Its tractors are sold on six continents. It has acquired plants in China[10] and the United Kingdom,[11] and has three assembly plants in the USA. M&M has partnerships with international companies like Renault SA, France[12] and International Truck and Engine Corporation, USA. At the 2008 Delhi Auto Show, Mahindra executives said the company is pursuing an aggressive product expansion program that would see the launch of several new platforms and vehicles over the next three years, including an entry-level SUV designed to seat five passengers and powered by a small turbodiesel engine.[19] True to their word, Mahindra & Mahindra launched the Mahindra Xylo in January 2009, and as of June 2009, the Xylo has sold over 15000 units.[20] Also in early 2008, Mahindra commenced its first overseas CKD operations with the launch of the Mahindra Scorpio in Egypt,[21] in partnership with the Bavarian Auto Group. This was soon followed by assembly facilities in Brazil. -

'18-'13 Af5220 Ca11450 A46297 49073 Ma10004

stockcode application CHAMP FRAM PERFORMAX PUROLATOR WIX MA10003 NISSAN ALTIMA 2.5L '18-'13 AF5220 CA11450 A46297 49073 MA10004 ACURA RDX '13-'18 AF5218 CA11413 A36276 49211 MA10005 HONDA ACCORD '17-'13 2.4L, ACURA TLX 2.4 '19-15 AF5222 CA11476 PA-600 A26282 49750 MA10006 HONDA ACCORD '17-'13 3.5L, ACURA TLX 3.5L '19-15 AF5223 CA11477 PA-601 A26283 49760 MA10007 HYUNDAI SANTA FE SPORT '19-'13 AF5224 CA11500 A36320 49670 MA10014 PRIUS, PRIUS C '19-'12 AF5216 CA11426 WA10000 MA10015 CHEVROLET MALIBU, IMPALA '19-'13 2.5L AF3174 CA11251 PA-603 A46279 WA10254 MA10016 CADILLAC XTS '17-'13; CHEVROLET IMPALA '19-'18 AF3176 WA10039 MA10017 DODGE DART '15-'13 AF5219 CA11431 A26281 A26281 WA10008 MA10018 INFINITI M35h '12, Q70 '18-14 MA10019 HONDA CR-V '14-'12 AF5210 CA11258 A36274 49630 MA10025 NISSAN VERSA 1.6L '19-'12 AF5207 CA11215 PA-598 A16202 49038 MA10175 VW JETTA 2.0L NAT. ASP. (CBPA) '17-'11 AF3611 CA9800 49013 MA10178 LAND ROVER LR4, RANGE ROVER 5.0L '18-'10 CA11062 49593 MA10181 CHEVROLET MALIBU 2.0L TURBO '15-'13 (BUICK REGAL) AF3174 CA11251 A46279 WA10253 MA10182 VOLKSWAGEN JETTA HYBRID '17-13, AUDI A3 1.4L '18 AF3619 A93619 WA10072 MA10183 AUDI RS5 '13 MA10184 LAND ROVER LR2, RANGE ROVER EVOQUE '17-'13 AF3615 CA11485 WA10007 MA10187 CHEVROLET SPARK '13 AF5221 CA11469 A26277 49264 CADILLAC ATS '18-'13 (2L, 2.5L, 3.6L) CHEVROLET CAMARO MA10188 '19-'16 AF3178 CA11494 A58153 49830 MA10190 BMW 2-,3-,4-SERIES 2.0L TURBO GAS '18-'12 CA11305 A93618 WA10005 MA10215 BUICK ENCORE '18-'13; CHEVROLET TRAX '19 AF3184 CA11501 A26319 WA10255 MA10216 -

1 Fundamental Car Groups, 1981-2011

FUNDAMENTAL CAR GROUPS, 1981-2011 (Shared Body Platforms) 1. The first line of the definition assigns a five-digit number to the car group; the first two digits indicate the manufacturer, based on FARS codes (1=AMC, 6=Chrysler, 12=Ford, 18=GM, etc.); the last three digits are sequential and generally chronological for that manufacturer. 2. The second line assigns a name to the car group and gives the limits of the range of model years for the various make-models in the car group. Car groups are often named after the largest selling make-model with that body platform and/or the wheelbase of that platform (to the nearest inch). 3. The third line shows the wheelbase of the cars in that group, as derived from "New Car Specifications" in Automotive News or Ward’s Automotive Yearbook. 4. The remaining lines list the specific make-models included in the car group, including a five-digit make-model code, the make-model name (plus additional specifications such as "4-door" if not every car of that make-model is in that car group during the specified time period), a range of model years, and the VIN characters that identify specifically which cars belong to this car group (V3 is the 3rd character of the VIN, V34 is the 3rd and 4th character, etc.). American Motors Car Groups Car group 1008 AMC Gremlin/Spirit, 1981-1983 Wheelbase 96 1008 AMC Spirit 1981-1983 V6=4 V3=M Car group 1009 AMC Hornet/Concord, 1981-1983 Wheelbase 108 1007 AMC Concord, 1981-1983 V6=0 Car group 1011 AMC Eagle, 1981-1988 Wheelbase 109.3 1009 AMC Eagle, 1981-1988 V6=3 Car group 1012 AMC SX4, 1981-1983 Wheelbase 97.2 1010 AMC SX4/Kammback, 1981-1983 V6=5 1 Chrysler Corp. -

Increased Automobile Fuel Efficiency and Synthetic Fuels: Alternatives for Reducing Oil Imports

Increased Automobile Fuel Efficiency and Synthetic Fuels: Alternatives for Reducing Oil Imports September 1982 NTIS order #PB83-126094 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 82-600603 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This report presents the findings of an assessment requested by the Senate Com- mittee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. The study assesses and compares increased automobile fuel efficiency and synthetic fuels production with respect to their potential to reduce conventional oil consumption, and their costs and impacts. Con- servation and fuel switching as a means of reducing stationary oil uses are also con- sidered, but in considerably less detail, in order to enable estimates of plausible future oil imports. We are grateful for the assistance of the project advisory panels and the many other people who provided advice, information, and reviews. It should be understood, how- ever, that OTA assumes full responsibility for this report, which does not necessarily represent the views of individual members of the advisory panels. Director Automobile Fuel Efficiency Advisory Panel Michael J. Rabins, Chairman Wayne State University Maudine R. Cooper* John B. Heywood National Urban League, Inc. Massachusetts Institute of Technology John Ferron John Holden National Automobile Dealers Association Ford Motor Co. Donald Friedman Maryann N. Keller Minicar, Inc. Paine, Webber, Mitchell, & Hutchins Herbert Fuhrman Paul Larsen National Institute for GMC Truck and Coach Division Automobile Service Excellence Robert D. Nell James M. Gill Consumers Union The Ethyl Corp. Kenneth Orski R. Eugene Goodson** German Marshall Fund of the United States Hoover Universal, Inc. -

Trends in the Static Stability Factor of Passenger Cars, Light Trucks, and Vans

DOT HS 809 868 June 2005 NHTSA Technical Report Trends in the Static Stability Factor of Passenger Cars, Light Trucks, and Vans This document is available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear only because they are considered essential to the object of this report. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. DOT HS 809 868 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date June 2005 Trends in the Static Stability Factor of Passenger Cars, Light Trucks, and Vans 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Marie C. Walz 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Office of Regulatory Analysis and Evaluation Planning, Evaluation and Budget 11. Contract or Grant No. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Washington, DC 20590 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Department of Transportation NHTSA Technical Report National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract Rollover crashes kill more than 10,000 occupants of passenger vehicles each year. As part of its mission to reduce fatalities and injuries, since model year 2001 NHTSA has included rollover information as part of its NCAP ratings. One of the primary means of assessing rollover risk is the static stability factor (SSF), a measurement of a vehicle’s resistance to rollover. The higher the SSF, the lower the rollover risk. -

2003 Chevrolet Venture

2003 CHEVY VENTURE 2003 CHEVY VENTURE FEATURES: CHEVY VENTURE ■ 185-hp, 3400 V6 engine ■ Air conditioning and Solar-Ray glass FAMILY-FRIENDLY ■ Available seating plans for up to eight passengers (LS and Warner Bros. models) FUN TRAVELER. ■ Up to 140.7 cu. ft. of cargo space (extended wheelbase models) ■ Four-wheel ABS (optional on Value Van and Plus Van) Wherever you’re going, Chevy Venture makes travel fun for everybody. And you can be sure there’s a Venture exactly right for your family, thanks to a wide range of models and seating plans. Depending on the model, you can opt for dual power sliding side doors, a third-row stowable seat, and Versatrak — a versatile, all-wheel-drive traction system. You’ll love the response of the standard V6 engine (with the highest highway MPG in its class*) and you’ll feel secure knowing that Venture surrounds you and your passengers with a comprehensive safety package. Chevy Venture. It’s the perfect fit for your family’s travel adventures. *Estimated MPG 19 city, 26 highway (front-wheel-drive models), 18 city, 24 highway (all-wheel-drive models). Based on front-wheel-drive and all- Venture Warner Bros. Edition all-wheel-drive model in Galaxy Silver Metallic. wheel-drive minivans using 2002 competitive information. 2003 Venture mileage estimates based on GM testing. Official EPA estimates not yet available. 0 2 WARNER BROS. EDITION THE MAIN ATTRACTION. Take the show on the road with the Venture Warner Bros. Edition with entertainment features that will have you inventing reasons for going places. -

Assembly Guide for Plastic Mounting Kits for 1982-2004 Ford, GM and Mopar Vehicles

Assembly Guide for Plastic Mounting Kits for 1982-2004 Ford, GM and Mopar Vehicles The information enclosed in this installation manual is to be used as a guide to assist you during the process of installation. This guide does not cover every installation possibility, vehicle, or every aspect of the installation process. Retro Manufacturing, LLC, RetroSound®, or its subsidiaries, assume no responsibility for any installation. This manual may be updated from time to time. Please check our website for the latest updates: retrosound.com. 1 2 3 4 ZONE REV. DESCRIPTION DATE ISSUE BY C B A ITEM PART NO. PART NAME QTY. MATERIAL SPEC. MODEL NAME MATERIAL/COLOR MODEL NO. CAVITY QTY. UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED DRAWN DATE 1, REMOVE ALL BURRS & SHARP CORNERS. 2, ALL DIMENSION ARE IN MILLIMETER ( ) mm APPD. DATE 3, TOLERANCE ARE LINEAR : .X ± 0.1 TOOL NO. .XX ± 0.05 DWG. FILE SHT. ANGULAR : ± 0.25° SCALE REV. GM, Ford and Mopar Plastic Mounting Kit Assembly Guide Table of Contents (GM Applications) BUICK CHEVROLET (cont.) Century 1982-96*........................7 Suburban 1989-91*.....................9 Electra 1984-94*.........................7 Suburban 1995-02......................10 Estate wagon 1984-94*.............. 7 Tahoe 1995-02............................10 LeSabre 1984-94*.......................7 Van (full) 1988-95........................13 Park Ave. 1984-94*.....................7 Venture 1997-99.........................15 Reatta 1990-91*..........................7 GMC Regal 1984-87*...........................7 Jimmy (full) 1989-91*..................9 Riviera 1983-85*.........................7 Jimmy 1998-02...........................10 Riviera 1990-95*.........................7 S15 Jimmy 1982-85....................17 Roadmaster 1991-94..................8 S15 Jimmy 1986-94....................18 Skyhawk 1982-89*......................9 S15 Pickup 1982-85....................17 Skylark 1983-85*.........................9 S15 Pickup 1986-93....................18 Skylark 1987-89*.........................9 Safari 1985-89........................... -

2004 Chevrolet Venture Owner Manual M

2004 Chevrolet Venture Owner Manual M Seats and Restraint Systems ........................... 1-1 Driver Information Center (DIC) .................. 3-57 Front Seats ............................................... 1-3 Audio System(s) ....................................... 3-60 Rear Seats ............................................... 1-6 Driving Your Vehicle ....................................... 4-1 Safety Belts ............................................. 1-30 Your Driving, the Road, and Your Vehicle ..... 4-2 Child Restraints ....................................... 1-57 Towing ................................................... 4-33 Air Bag Systems ...................................... 1-94 Service and Appearance Care .......................... 5-1 Restraint System Check .......................... 1-103 Service ..................................................... 5-3 Features and Controls ..................................... 2-1 Fuel ......................................................... 5-4 Keys ........................................................ 2-3 Checking Things Under the Hood ................. 5-9 Doors and Locks ....................................... 2-9 All-Wheel Drive ........................................ 5-51 Windows ................................................. 2-24 Bulb Replacement .................................... 5-52 Theft-Deterrent Systems ............................ 2-27 Windshield Wiper Blade Replacement ......... 5-59 Starting and Operating Your Vehicle ........... 2-32 Tires ..................................................... -

IVIC Notifications

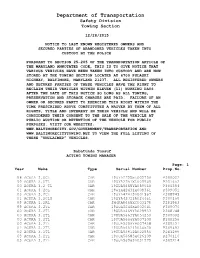

Department of Transportation Safety Division Towing Section 12/28/2015 NOTICE TO LAST KNOWN REGISTERED OWNERS AND SECURED PARTIES OF ABANDONED VEHICLES TAKEN INTO CUSTODY BY THE POLICE PURSUANT TO SECTION 25-205 OF THE TRANSPORTATION ARTICLE OF THE MARYLAND ANNOTATED CODE, THIS IS TO GIVE NOTICE THAT VARIOUS VEHICLES HAVE BEEN TAKEN INTO CUSTODY AND ARE NOW STORED AT THE TOWING SECTION LOCATED AT 6700 PULASKI HIGHWAY, BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 21237. ALL REGISTERED OWNERS AND SECURED PARTIES OF THESE VEHICLES HAVE THE RIGHT TO RECLAIM THEIR VEHICLES WITHIN ELEVEN (11) WORKING DAYS AFTER THE DATE OF THIS NOTICE SO LONG AS ALL TOWING, PRESERVATION AND STORAGE CHARGES ARE PAID. FAILURE OF AN OWNER OR SECURED PARTY TO EXERCISE THIS RIGHT WITHIN THE TIME PRESCRIBED ABOVE CONSTITUTES A WAIVER BY THEM OF ALL RIGHTS, TITLE AND INTEREST IN THEIR VEHICLE AND WILL BE CONSIDERED THEIR CONSENT TO THE SALE OF THE VEHICLE AT PUBLIC AUCTION OR RETENTION OF THE VEHICLE FOR PUBLIC PURPOSES. VISIT OUR WEBSITES: WWW.BALTIMORECITY.GOV/GOVERNMENT/TRANSPORTATION AND WWW.BALTIMORECITYTOWING.NET TO VIEW THE FULL LISTING OF THESE “UNCLAIMED” VEHICLES. Babatunde Yussuf ACTING TOWING MANAGER Page: 1 Year Make Type Serial Number Prop.No. 98 ACURA 3.0CL CAR 19UYA2255WL005756 P309032 99 ACURA 3.0TL CAR 19UYA2251XL009949 P297652 00 ACURA 3.2 TL CAR 19UUA5665YA059060 P306354 01 ACURA 3.2CL CAR 19UYA42431A009361 P309051 03 ACURA 3.2CL CAR 19UYA42413A001567 P308945 01 ACURA 3.2CLS CAR 19UYA42721A024461 P309159 99 ACURA 3.2RL CAR JH4KA9665XC003179 P291963 99 ACURA 3.2TL CAR 19UUA5646XA002041 -

Europe Swings Toward Suvs, Minivans Fragmenting Market Sedans and Station Wagons – Fell Automakers Did Slightly Better Than Cent

AN.040209.18&19.qxd 06.02.2004 13:25 Uhr Page 18 ◆ 18 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE FEBRUARY 9, 2004 ◆ MARKET ANALYSIS BY SEGMENT Europe swings toward SUVs, minivans Fragmenting market sedans and station wagons – fell automakers did slightly better than cent. The only new product in an cent because of declining sales for 656,000 units or 5.5 percent. mass-market automakers. Volume otherwise aging arena, the Fiat the Honda HR-V and Mitsubishi favors the non-typical But automakers boosted sales of brands lost close to 2 percent of vol- Panda, was on sale for only four Pajero Pinin. over familiar sedans unconventional vehicles – coupes, ume last year, compared to 0.9 per- months of the year. In terms of brands leading the roadsters, minivans, sport-utility cent for luxury marques. European buyers seem to pro- most segments, Renault is the win- LUCA CIFERRI vehicles exotic cars and multi- Traditional European-brand gressively walk away from large ner with four. Its Twingo leads the spaces such as the Citroen Berlingo automakers dominate the tradi- sedans, down 20.3 percent for the minicar segment, but Renault also AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE – by 16.8 percent last year to nearly tional car, minivan and premium volume makers and off 11.1 percent leads three other segments that it 3 million units. segments, but Asian brands control in the upper-premium segment. created: compact minivan, Scenic; TURIN – Automakers sold 428,000 These non-traditional vehicle cat- virtually all the top spots in small, large minivan, Espace; and multi- more specialty vehicles last year in egories, some of which barely compact and large SUV segments.