Leprosy in Karachi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dispositifs of (Dis)Order: Gangs, Governmentality and the Policing of Lyari, Pakistan Adeem Suhail

Dispositifs of (Dis)Order: Gangs, governmentality and the policing of Lyari, Pakistan Adeem Suhail Abstract: At a moment when the violence of policing has found its locus in the bureaucratic institutions of ‘the police’, anthropology offers a more expansive idea of policing as a social function, articulated through multiple social forms, and crucial to hierarchical orders. This article draws on the idea of the dispositif to offer a processual model for understanding how non-state violence abets the maintenance of social order. Exploring the limits of biopolitics and drawing on ethnographic evidence, it uses the case of gang activity in Lyari, Pakistan, to show how gangsters maintained, rather than disrupt, the dominant social order in the city. Furthermore, it shows that those who challenged the inherently violent and exploitative order implemented by the gangs and the city's political elite were prime targets of public violence wielded by law and outlaw working together as a dispositif. Introduction The policeman who collected him from the recycling depot did not offer any explanations which made Babu Maheshwari apprehensive. Things became clearer when a few blocks away they arrived at the drainage nala. Babu saw the boy floating face-down in the murky waters amidst the thick sludge of excreta, plastics, chemicals, and once-desired objects that form Karachi’s daily discharge. This mundanely repugnant ecology had claimed and begun consuming the boy. Babu, a veteran municipal waste worker hailing from the ex-untouchable Dalit communities of coastal Sind, was brung, once more, to be the instrument that reclaimed the body, as a once-desired object, now discarded by city into its rivers of shit. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Central-Karachi

Central-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 1-Kalyana 408130186 GBELS - Elementary Elementary Boys 20,253 4,051 16,202 4,051 4,051 16,202 64,808 16,202 81,010 2 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130163 GBLSS - 11-G NEW KARACHI Middle Boys 24,147 4,829 19,318 4,829 4,829 19,318 77,271 19,318 96,589 3 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130167 GBLSS - MEHDI Middle Boys 11,758 2,352 9,406 2,352 2,352 9,406 37,625 9,406 47,031 4 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130176 GBELS - MATHODIST Elementary Boys 20,492 4,098 12,295 8,197 4,098 16,394 65,576 16,394 81,970 5 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 6-Hakim Ahsan 408130205 GBELS - PIXY DALE 2 Registred as a Seconda Elementary Girls 61,338 12,268 49,070 12,268 12,268 49,070 196,281 49,070 245,351 6 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 9-Khameeso Goth 408130174 GBLSS - KHAMISO GOTH Middle Mixed 6,962 1,392 5,569 1,392 1,392 5,569 22,278 5,569 27,847 7 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130160 GBLSS - FARZANA Middle Boys 11,678 2,336 9,342 2,336 2,336 9,342 37,369 9,342 46,711 8 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130166 GBLSS - 5/J Middle Boys 28,064 5,613 16,838 11,226 5,613 22,451 89,804 22,451 112,256 9 Central Karachi New Karachi -

TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-E - Faisal

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Karachi TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-e - Faisal. 0316-9992201 2 Karachi TCS Office Main Head 101-104 CAA Club Road Near Hajj Tarminal - 3 0316-9992202 3 Karachi TCS Office Malir Cantt Shop#180 S-13 Cantt Bazar, Malir Cantonement, Karachi 0316-9992204 4 Karachi TCS Office Malir Court Shop # G-14 Al Raza Sq. New Malir City Near Malir Court 0316-9992207 Shop # 3Haq Baho shopping Center Gulshan e Hadeed Ph.1 Gulshan e 5 Karachi TCS Office Gulshan-E-Hadeed 0316-9992213 Hadeed 6 Karachi TCS Office Korangi No. 4 Shop # 10, Abbasi Fair Trade Centre, Korangi # 4 Opp. KMC Zoo 0316-9992215 7 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN Chowrangi Shop A 1/30, block No 5. Haider plaza gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi 0316-9992230 8 Karachi TCS Office GULISTAN-E-JOHAR Shop # Saima Classic Rashid Minas Road Near Johar More 0316-9992231 9 Karachi TCS Office HYDRI Shop # B-13, Al Bohran Circle, Block-B, North Nazimabad. 0316-9992232 10 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN-E-IQBAL Shop # 06, Plot # B-74 Shelzon Center BI.15 Opp. Usmania Restrent 0316-9992234 11 Karachi TCS Office ORANGI TOWN Banaras Town, Sector 8, Orangi Town Karachi Opp. Banaras Town Masjid 0316-9992236 12 Karachi TCS Office S.I.T.E Shop # 5, SITE Shopping Centre, Manghopir Rd. Opp. MCB SITE Br. 0316-9992237 13 Karachi TCS Office NIPA CHOWRANGI Shop # A -8 KDA Overseas apartment 0316-9992241 S 5 Noman Arcade Bl. 14 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Near Mashriq Centre Sir 14 Karachi TCS Office Mashriq Center 0316-9992250 suleman shah Rd. -

Life and Death in Lyari

Life and Death in Lyari The beaches and boardwalk at Clifton Beach A Further partition in Pakistan's port city of Karachi By FATIMA BHUTTO Published : 1 March 2010 1. KARACHI IS MY CITY, my home, but I was seven years old the first time I set foot on its soil. I was boarded onto a Pakistan International Airlines plane by my father from our exile home in Syria, and told I would be seated next to an old Sindhi woman who would look after me should I need anything. We never said a word to each other, the old Sindhi woman and I. She smiled at me nervously from time to time, and I grimaced back. I was anxious. It was my first time flying alone, my first time going home. Sometime after midnight the crew of PIA stewardesses, clad in deep green shalwar kameez with their pastel flowered dupattas neatly pinned across their shoulders, filed out along the aisles holding a cake and singing Happy Birthday to a Very Important Passenger. Everyone on board clapped and waited patiently for a piece of birthday cake. I didn't sleep a wink that night. My grandmother, Joonam as I called her in her native Farsi, picked me up that bright December morning at Karachi's Jinnah airport. At the time, it looked like a small bus shed. Cement walls, grey and unpainted, dirty tiled floors and creaking baggage belts, badly needing to be oiled. In the city, palm trees that bore coconuts, not the dates our palms carried in Damascus, lined the wide streets. -

Sindh Government Hospital Liaquatabad, Karachi Basis

SINDH GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL LIAQUATABAD KARACHI. TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF FOR THE YEAR 2015-16 PURCHASE OF MEDICINES & LABORATORY KITS/CEHEMICALS 15 % / MEDICAL GASES/ DIET / MISCELLANEOUS ARTICLES REPAIR OF FURNITURE/TRANSPORT/ MACHINERY & EQUIPMENTS. SCHEDULE OF REQUIREMENTS & PRICES FOR THE CURRENT FINANCIAL YEAR 2015-16 TIME OF SALE FROM: Date of Publishing TIME OF OPENING TENDER: 31ST August, 2015 at 12:00 Noon Offer will remain open for 60 days from the date of opening. The tenders shall quote their prices inclusive of all duties/taxes/octori/transportation etc and all other expenses on free delivery to consignee’s end at Sindh Government Hospital Liaquatabad, Karachi basis. Price should be quoted in figures and words both, failing which the offer will be ignored. S# Nomenclature/Product Quantity Rate Amount Name Demanded Delivery Period: within 15 days Validity TILL 30 JUNE, 2016 1 The tender shall be submitted with all documents in sealed envelopes, with sealing wax. The envelope must contain tender enquiry number on the top.; the name of the manufacturer and the supplier should be affixed on the face of every envelope at the left side. 2 Tender must be filled in Blue or Black ink in the column provided/on separate letter head duly signed. 3 The tender must be free from erasing, cutting and over writing. In case of erasing, cutting and over writing authorized person should initial it. 4 The rates of each item should be written in figures as well as in words. Arithmetical errors will be rectified on there basis, if there is discrepancy between the unit price and the total price that is obtained by multiplying the unit price and the quantity, the unit price shall prevail and the total price shall corrected. -

Public and Private Control and Contestation of Public Space Amid Violent Conflict in Karachi

Public and private control and contestation of public space amid violent conflict in Karachi Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan Working Paper Urban Keywords: November 2015 Urban development, violence, public space, conflict, Karachi About the authors Published by IIED, November 2015 Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Noman Ahmed: Professor and Chairman, Department of Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan. 2015. Architecture and Planning at NED University of Engineering Public and private control and contestation of public space amid and Technology in Karachi. Email – [email protected] violent conflict in Karachi. IIED Working Paper. IIED, London. Bushra Owais Siddiqui: Young architect in private practice in http://pubs.iied.org/10752IIED Karachi. Email – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-78431-258-9 Dure Shahwar Khalil: Young architect in private practice in Karachi. Email – [email protected] Printed on recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Sana Tajuddin: Lecturer and Coordinator of Development Studies Programme at NED University, Karachi. Email – sana_ [email protected] Donald Brown: IIED Consultant. Email – donaldrmbrown@gmail. com Gordon McGranahan: Principal Researcher, Human Settlements Group, IIED. Email – [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements Group The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of Africa, Asia -

Research Paper Groundwater Quality Assessment Using Water Quality Index

Academia Journal of Environmental Science 5(6): 095-101, June 2017 DOI: 10.15413/ajes.2017.0113 ISSN: ISSN 2315-778X ©2017 Academia Publishing Research Paper Groundwater quality assessment using water quality index (WQI) in Liaquatabad Town, Karachi, Pakistan Accepted 22nd June, 2017 ABSTRACT The aim of the present study is to evaluate the groundwater quality of Liaquatabad Town using water quality index (WQI) measured through physico- chemical parameters. For this purpose, groundwater samples (n = 31) were randomly collected through boring wells from various sites of study area. Data revealed that TDS content of groundwater is very high (mean: 1045.55 mg/L) which is double the WHO limit for drinking purpose. Elevated concentrations of Ca, Na, Cl, and HCO3 is reported in 85, 33, 40 and 70% wells respectively, which exceeded the corresponding WHO guideline for drinking purpose. Very high concentration of these major ions (Ca, Na, Cl, and HCO3) is indicative of sewage Adnan Khan* and Yusra Rehman mixing with groundwater in Liaquatabad. The calculated value of water quality index (WQI = 66.1) shows that groundwater in Liaquatabad town is not suitable Department of Geology, University of for drinking purpose but can be used for industrial and irrigation purpose. Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan. *Corresponding author. Email: Keywords: Groundwater quality, physio-chemical parameters, water quality [email protected]. index, Liaquatabad town. INTRODUCTION Water is an essential component of all forms of life; no the modern civilization, industrialization, urbanization, organism can survive without water. Daily demand of increase in population and improper waste management drinking water of a man is normally 7% of his body weight are agents of degradation of groundwater quality (Iqbal and Gupta, 2009) but this water can become a threat (Agarwal, 2009). -

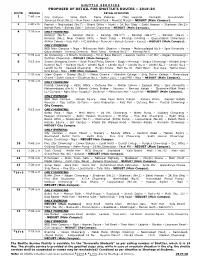

Shuttle Route

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

Appendix 4-1 Desirable Plan for Station Plaza Proposed in SAPROF-I Desirable Plaza Plans at Each Station Are Shown in the Following Figures with Satellite Images

APPENDIX 4-1 Desirable Plan for Station Plaza Proposed in SAPROF-I Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final Report Appendix 4-1 Desirable Plan for Station Plaza Proposed in SAPROF-I Desirable plaza plans at each station are shown in the following figures with satellite images. (1) Drigh Road Station Structure Station Plaza (2) Johar Source: SAPROF-I Figure 1 Desirable Station Plaza Plan (1/12) APP4-1-1 Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final Report (3) Alladin Park Station Structure Station Plaza (4) Nipa Source: SAPROF-I Figure 2 Desirable Station Plaza Plan (2/12) APP4-1-2 Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final Report (5) Gilani Station Structure Station Plaza (6) Yasinabad Source: SAPROF-I Figure 3 Desirable Station Plaza Plan (3/12) APP4-1-3 Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final Report (7) Liaquatabad Station Structure Station Plaza (8) North Nazimabad Source: SAPROF-I Figure 4 Desirable Station Plaza Plan (4/12) APP4-1-4 Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final Report (9) Orangi Station Structure Station Plaza (10) HBL Source: SAPROF-I Figure 5 Desirable Station Plaza Plan (5/12) APP4-1-5 Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final Report (11) Manghopir Station Structure Station Plaza (12) SITE Source: SAPROF-I Figure 6 Desirable Station Plaza Plan (6/12) APP4-1-6 Preparatory Survey (II) on Karachi Circular Railway Revival Project Final -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study.