Time for Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-House. March 20

'1718 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. MARCH 20, By Mr. HILL: The petitions of W. Wrede and 100 others, of F. CHANGES OF REFERENCES. Duok and 100 others, of John Mason and others, of J. W. Berry and Changes of references of petitions were made, under the rule, as 100 others, citizens of Defiance and Williams Counties, and of Cas follows: per Kahl and 100 others, citizens of the sixth district of Ohio, soldiers The petition of W. B. Wellgwood, vice-chancellor of the National of the United States Army, engaged in the late war, for the early University-from the Committee on Appropriations to the Commit passage of a law providing for the payment of the difference between tee on Education and Labor. the value of the greenbacks, in which they were paid for their serv The petitions of Eban B. Grant and others; of Bernard McCormick ices, and the value of gold at the time of payment-to the Commit and 6 other~ of C. J. Poore and 122 others, citizens of Michigan; of tee on Military Affairs. citizens of l.Jolville, Washington Territory, and of citizens of Wash 1 By Mr. JOSEPH J. MARTIN: The petition of the publisher of the ington Territory-from the Committee on Appropriations to the Com Falcon, Elizabeth City, North Carolina, that materials used in mak mittee on ~tary Affairs. ing paper be placed on the free µst, and for the reduction of the duty on printing-paper-to the Committee on Ways and Means. By Mr. McKENZIE: The petitions of J.M. Nicholls and Charles W. -

ANALYSIS the Official UK Singles & Albums Charts Are Compiled by the Official Charts Company, Based on a Sample of More Than 15,000 Physical and Digital Outlets

ANALYSIS The Official UK Singles & Albums Charts are compiled by the Official Charts Company, based on a sample of more than 15,000 physical and digital outlets. They count actual sales and audio streams from last Friday to Thursday, based on sales of downloads, CDs, vinyl and other physical formats and audio streams weighted using SEA2 methodology. Highway to hell: Lewis Capaldi returns to top spot with debut album Q BY ALAN JONES ethroned by Bruce Springsteen last week, and trailing Will Young for much of the latest frame, Lewis DCapaldi edged past the latter to return to No.1. The Scot’s debut, Divinely Uninspired To A Hellish Extent, bounces 3-1 to secure its fifth week at the summit, although its sales are off 21.00% week-on-week to 19,003 (including 11,085 from sales-equivalent streams) its lowest haul yet. Denied his fifth No.1 album at the death, Will Young’s seventh studio set, Lexicon, opens at No.2 on sales of 16,706 copies. He thus remains tied with Cheryl (two solo, two with Girls Aloud), One Direction and Olly Murs as the reality TV graduates with most No.1 albums. Lexicon is No.1 on both physical sales (11,752) and paid-for downloads (4,274), being No.1 let down only by streaming. Recording Young’s lowest first week sale for a studio album yet, it is the successor to 85% Proof, which previously held that record with 21,320, but which Lewis Capaldi - Divinely Uninspired To A Hellish Extent (Virgin EMI) nevertheless opened at No.1 in 2015, and has sold 96,356 copies. -

Photosystem Ii Reactions in Thylakoid Membranes

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. I.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

Cofactors on the Donor Side of Photosystem II Investigated with EPR Techniques

Cofactors on the Donor Side of Photosystem II Investigated with EPR Techniques vorgelegt von Diplom-Chemiker Michael Kammel aus Laage von der Fakult¨at II -Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften- der Technischen Universit¨at Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften - Dr. rer. nat. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Martin Lerch Berichter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Lubitz Berichter: Prof. Dr. Robert Bittl Tag der mundlic¨ hen Prufung:¨ 23.06.2003 Berlin 2003 D 83 Zusammenfassung Michael Kammel: Cofactors on the Donor Side of Photosystem II investigated with EPR techniques Dem Photosystem II, mit dessen Hilfe es h¨oheren Pflanzen und Cyanobakterien gelingt, Wasser zu oxidieren, wird seit Jahrzehnten die Aufmerksamkeit der Forscher vieler Fachgebiete zuteil. Die Kofaktoren im Photosystem II durchlaufen im Rahmen der lichtinduzierten Ladungstren- nung paramagnetische Zust¨ande. Diese k¨onnen mit den Techniken der Elektronen-paramagne- tischen Resonanz erfasst werden. Dies erlaubt Aussagen ub¨ er Kinetik und Mechanismen der Ladungstrennungsreaktionen, sowie ub¨ er Ort und Orientierung der daran beteiligten Kofak- toren. Der erste Teil der Arbeit befasst sich mit dem Beginn der lichtinduzierten Ladungstrennung. Durch eine Blockade des prim¨aren Elektronentransfers war es m¨oglich, eine Rekombination am Ort der ursprunglic¨ hen Ladungstrennung zu induzieren. Es entsteht ein Triplettzustand, welcher sich mit zeitaufgel¨oster EPR detektieren l¨asst. Durch die Verwendung von Kristallen des PS II und der orientierungsabh¨angigen Messung des EPR-Signals konnte der Ort der Rekombination ermittelt werden und Aussagen ub¨ er die Ladungstrennung gemacht werden. Der zweite Teil ist der redoxaktiven Aminos¨aure YD des die Kofaktoren umgebenden Pro- teingerustes¨ gewidmet. Sie liegt im Photosystem als metastabiles Radikal vor. -

Hot Chip Confirmados No Nos Alive'19

COMUNICADO DE IMPRENSA 22 / 01 / 2019 NOS apresenta dia 11 de julho no Palco Sagres HOT CHIP CONFIRMADOS NO NOS ALIVE'19 Hot Chip são a mais recente confirmação para dia 11 de julho do NOS Alive’19. Os britânicos sobem ao Palco Sagres no primeiro dia do festival, juntando-se assim aos já anunciados Jorja Smith, Robyn, Sharon Van Etten, Xavier Rudd e Emicida. A banda, formada em Londres por Alexis Taylor, Joe Goddard, Owen Clarke, Felix Martin e Al Doyle, é considerada uma das mais distintas e inovadoras das últimas duas décadas pelo facto de ter começado a combinar dance music e indie no início dos anos 2000. Hoje, conta com seis álbuns editados no seu repertório: “Coming on Strong” (2004), “The Warning” (2006), “Made in the Dark” (2008), “One Life Stand” (2010), “In Our Heads” (2012) e “Why Make Sense?” (2015). Os Hot Chip começaram desde cedo a chamar a atenção da crítica e do público. No entanto, foi em 2006, com o disco “The Warning”, que ganharam alcance mundial com a nomeação nos Mercury Music Prize, na categoria de Melhor Álbum, tendo o tema “Over and Over" sido ainda considerado o melhor single de 2006, pela conceituada revista de música NME. Já em 2009, “Ready For the Floor”, música integrante do álbum “Made In The Dark”, recebeu uma nomeação para os Grammy Awards na categoria de Best Dance Recording. Hot Chip vão percorrer os temas de 19 anos de carreira dia 11 de julho, no Palco Sagres do NOS Alive’19. Artistas confirmados: Bob Moses (Club Set), Bon Iver, Cut Copy, Curadoria Bridgetown (Carla Prata, Dillaz, DJ Dadda, Nubai Soundsystem, Plutonio, Saint Jhn, Trace Nova e Lé Vie), Emicida, H.E.R, Hot Chip, IDLES, Izal, Jorja Smith, Ornatos Violeta, Pip Blom, Robyn, RY X, Sharon Van Etten, Tash Sultana, The Chemical Brothers, The Cure, The Smashing Pumpkins, Vetusta Morla, Thom Yorke, Vampire Weekend, Vetusta Morla, Weezer e Xavier Rudd. -

Issue 151.Pmd

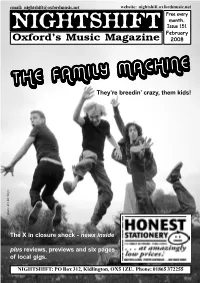

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 151 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2008 THETHE FAMILYFAMILYThey’re MACHINEMACHINEbreedin’ crazy, them kids! Rawlings photo:Alex The X in closure shock - news inside plus reviews, previews and six pages of local gigs. NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE X, in Cowley, has closed down after The Performing Rights Society (PRS) moved to have landlady Al declared bankrupt in a court hearing. Al had been in dispute with the PRS over payments due to for gigs held at the venue but had already paid the majority of the amount owed. The move to have her declared bankrupt came out of a court session on Thursday 17th January with immediate effect. As such the X was forced EELS return to Oxford for the first time in seven years when they play to close down that day and will remain shut until such time as its owners, at the New Theatre on Sunday 23rd March. The band are touring in the Punch, install a new manager. As leaseholder on the pub, All is no longer UK to promote a new Best Of Compilation, `Meet The Eels’ as well as allowed to continue trading and will undoubtedly lose her lease as a a rarities compilation, `Useless Trinkets’. Tickets for the show, priced consequence. £20, are on sale now from Ticketmaster on 0844 847 1505. Tickets Since taking over the X in 2002 Al has transformed a formerly run-down are also on sale now for Chris Rea on Sunday 30th March and James pub into one of the best small live music venues in Oxford, mainly on Saturday 19th April. -

February 2008 Pages 6-12, Minus 10

6 HIGH TIDE February 14, 2008 STUDENT FOCUS February 14, 2008 HIGH TIDE 7 Single and Don’t be Cliche this Loving It... That Lovin Feeling By Sarah Wright Valentine’s Day Staff Writer By Anton Swain-Gill Staff Writer Valentine’s Day is a day for couples to share their love, buy candy, and give into the Hallmark industry. This is why single ove. L . Valentine’s day is a wonderful holiday people should replace Valentine’s Day with singles day on y We th . h that celebrates love and lovers. You have February 14 . There are many things single people can W H e the chance to woo a new love, or tell your do on Valentine’s Day and still have fun. a W signifi cant other how much you appreciate t them. However, Valentine’s Day has become While most people will be sitting at e incredibly cliche, and if the same old roses home eating the and expensive dinner come to mind, here are Rock chocolate they got from . a few alternative ideas to make this holiday y By Angie Rosal-White Valentine s Day By Lena Rothstein out of the ordinary. their valentine or out on a ’ Staff Writer Editor-In-Chief big dinner date, one can opt h . Climbingto exercise with a friend To many people, Valentine’s Day can be expressed through a box of chocolates, Every year when February 14th rolls around, Americans in a fun way. Take a This year, we a dozen roses, or simply a homemade greeting card. -

The Obsession ++ Confession Issue Issue 5

THE OBSESSION ++ CONFESSION ISSUE #5 / 2012 $9.99US $9.99CAN SHIRLEY MANSON / SANTIGOLD / BEACH HOUSE SPIRITUALIZED / MARINA & THE DIAMONDS / GOTYE GABRIEL MANN / M.WARD ++MORE ISSUE 5 SO WHAT IF PAGES 8 - 19 READ THE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR MEET THE CONTRIBUTORS YOU CANNOT HIDE. I CAN’T STOP THINKING ABOUT PAGES 20 - 57 SANTIGOLD BEACH HOUSE MARINA AND THE DIAMONDS SHIRLEY MANSON SPIRITUALIZED GABRIEL MANN ALEXANDRA BRECKENRIDGE GOTYE BRADLEY SOILEAU I TOLD MY GIRLS HE COULD GET IT WANTING TO LIKE BE WITH YOU (WITH YOU) PAGES 58-83 NICK WATERHOUSE LISSY TRULLIE SAMANTHA RONSON MIIKE SNOW TYLER BLACKBURN M.WARD SHANE WEST INDIA DE BEAUFORT THE TING TINGS OF MONTREAL SILVERSUN PICKUPS HOT CHIP R.I.P TO THE GIRL YOU USED TO KNOW EVERYONE THINKS YOU’RE FUCKING HOT i know you want to find out about this PAGES 84- 109 ALEX PRAGER DESIGNER OBSESSIONS +CONFESSIONS IN GOD WE TRUST PEOPLE WE LIKE STOLEN GIRLFRIENDS CLUB CONFESSIONS OF A BUNNY LOVER DIRTY SECRETS QUIZ STAFF OBSESSIONS AND CONFESSIONS ON THE STREET SUNGLASSES STOPPING THE WORLD AND MELTING WITH YOU SERIOUSLY DUDE Sweater, THE REFORMATION. Dress, SAVANT. Leggings, IRO. P 110-11 HONEY BUNNY I AM ERICA KANE CONTRIBUTORS Koko Ntuen Editor-In-Chief + Publisher MICHAEL DONOVAN Polly Brown Michael Donovan has found a strong underground following Guest Art Director for being the harbinger of the Post Bourgeois art movement. Mixing fashion and fine art, his distinguishable raucous and raw style mixed with his aggressive nature has been applied to Heather Seidler work for Bullet, Wonderland, Lovecat and many others while Editorial + Music Director his more conservative and exciting observant work has been applied to clients including The Pierre Hotel, MAGIC/Project, Reed Smith, Marie Claire Turkey, and others. -

Irmin Schmidt (Can) and Kumo (Aka Jono Podmore): London, March 4, 2008 (Peter Guy: Getintothis) 14.04.08 16:48

Irmin Schmidt (Can) and Kumo (aka Jono Podmore): London, March 4, 2008 (Peter Guy: Getintothis) 14.04.08 16:48 www.workshoplive.com Feedback - Ads by Google Ads by Google Police Tour Comedy Festival Schweiz Tour Rem London « icLiverpool Homes Jobs Merseyside Motors Grab my RSS feed Add to: Google, MyYahoo, Bloglines, My AOL Search the site Search here... Go Grab my RSS feed | (What's this?) Profile... Latest Posts... Categories Irmin Schmidt (Can) and Kumo (aka Jono Podmore): Albums of the Week London, March 4, 2008 Banter Tags: Axolotl Eyes Can Cologne Flies Future Days Guys & Choirs Irmin Schmidt Jono End of Year Review Podmore krautrock Kumo Liverpool Liverpool Daily Post Masters of Confusion Tago Mago Guest Slot Peter Guy discovered music late. Posted by Peter Guy on March 12, 2008 2:00 AM | Permalink Introducing Since then he's been making up for it. With a collection to rival a small record Labels of Love shop and a gig diary fit for any addled groupie, music is is his religion. Listening Post: Sometimes he dreams of having Liam, Unsigned Scene with Prince and Jimmy Page round for tea Matt Eland but most of the time he can be found Louden Up - Live writing and designing the Daily Post's sports pages. Getintothis is his guide reviews to music, which he hopes you’ll On Track contribute to. On it Tag cloud... Pop Life 101 Tambourines 13 Blues For Thirteen Reel Music Moons 19 2007 2007 Nationwide Anyone who is serious about music, seriously loves Can. Mercury Music Prize 2008 2ManyDJs As The Rough Guide to Rock states: 'There is a significant lobby among rock Shuffle: Spins from the 3121 3rd Degree Festival 45:33 4AD 6 fans - and probably an even stronger one among musicians - that Can were the headphone jukebox of 1 thing 65daysofstatic A Hawk and a greatest band ever. -

Fullerton Bank Robbed Coffee Shop by Donald C

Vol. 87 Issue 8 February 18, 2010 Long Beach to hold comic convention Saturday The Long Beach convention center will host a comic expo Feb. 20, which will feature over 50 entertainment and comic book professionals. THURSDAY NEWS, Page 3 Insensitive to show Olympic luge athlete’s death? OPINION, Page 4 Titan hockey forward heavy hitter on the ice SPORTS, Page 8 The Student Voice of California State University, Fullerton Fullerton bank robbed Coffee shop BY DONALD C. STEFANOVICH The note demanded cash and and has a tattoo on the left side Daily Titan News Editor claimed the suspect had a gun, of his neck and another intricate AND JULIANA CAMPBELL according to police. tattoo on his left calf. survives amidst Daily Titan Staff Writer The suspect, described as Employees of nearby busi- [email protected] a Caucasian male in his early nesses claimed not to have seen 30s and approximately 5 feet 6 anything unusual. Wachovia The Wachovia Bank, located inches tall with a medium build, Bank officials refused to com- Fullerton bars at 1901 N. Euclid in Fullerton, thanked the teller after receiving ment. was robbed by an unidentified an undisclosed amount of mon- Police are asking for the pub- male Wednesday. ey, Goodrich said. lic’s help in identifying the sus- According to Fullerton Po- He walked out the north pect. lice Sgt. Andrew Goodrich, door of the bank and was last Anyone with information the suspect entered the bank seen running north through the about the incident is asked to PHOTO COURTESY FULLERTON POLICE DEPARTMENT and handed a note to the teller parking lot. -

Reason in Religion George Santayana

The Life of Reason: Reason in Religion George Santayana Based on the texts originally published in 1905. The Santayana Edition www.iupui.edu/~santedit/sant/ REASON IN RELIGION CHAPTER I HOW RELIGION MAY BE AN EMBODIMENT OF REASON Experience has repeatedly confirmed that well-known maxim of Bacon’s, that “a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism, but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion.” In every age the most comprehensive thinkers have found in Religion certainly the religion of their timeReligion and country and Reason something they could significant. accept, interpreting and illustrating that religion so as to give it depth and universal application. Even the heretics and atheists, if they have had profundity, turn out after a while to be forerunners of some new orthodoxy. What they rebel against is a religion alien to their nature; they are atheists only by accident, and relatively to a convention which inwardly offends them, but they yearn mightily in their own souls after the religious acceptance of a world interpreted in their own fashion. So it appears in the end that their atheism and loud protestation were in fact the hastier part of their thought, since what emboldened them to deny the poor world’s faith was that they were too impatient to understand it. Indeed, the enlighten- ment common to young wits and worm-eaten old satirists, who plume themselves on detecting the scientific ineptitude of religion—something which the blindest half see—is not nearly enlightened enough: it points to notorious facts incompatible with religious tenets literally taken, but it leaves unexplored the habits of thought from which those tenets sprang, their original meaning, and their true function.