Essay by Senator Tom Cotton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack's Costume from the Episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H

Jack's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 572 Jack's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H... 300 Jack's suit from "There's No Place Like Home, Part 1" 200 573 Jack's suit from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 950 Home... 300 200 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown" 574 - 800 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown." Jack's bl... 300 200 Jack's Season Four costume 575 - 850 Jack's Season Four costume. Jack's gray pants, stripe... 300 200 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume 576 - 1,400 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume. Jack's white lab... 300 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs 200 577 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs. Jack's DHARMA - 1,300 scrub... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 578 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 1,100 H... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 579 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 900 H... 300 Kate's black dress from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 580 Kate's black dress from the episode, "There's No Place - 950 Li... 300 200 Kate's Season Four costume 581 - 950 Kate's Season Four costume. Kate's dark gray pants, d... 300 200 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown" 582 - 900 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown." K... 300 200 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist 583 - 5,000 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist." Kat.. -

Bwdal Section This Wee -'*&>

ST. JOHNS-An 11-year-old Pewamo- St. Johns area entries in the nine-year Droste also won a $500 savings bond Westphalia area schoolboy won the ninth Clinton Derby history. Westphalia area for topping the other 77 gravity-race running of the Clinton County Soap Box entries have dominated the event during drivers. Derby Sunday, Tony Droste, R-2, Fowler, the past several years. topped the 78-car field and won a bid Names were drawn during the program The Derby Day opened Sunday after naming the 10 lucky boys who will be at national fame by being eligible for the noon with a huge parade through down able to attend the national finals. World Championship race at Akron, Ohio, town St. Johns. The race was officially They are Ricky Hanses, Leonard Lewis, later this summer. started with the ceremonial running of Kurt Black, Pete Soliz, Randy Sonier, GU Weber, 14, of Pewamo came in second last year's winner Roy Fedewa, Once Roy Bill Wager, Rick Atkinson, Jim Light, Tragic accident fakes in the Sunday afternoon race and third spot crossed the finish line the races were practice periods conducted in Rochester, was taken by Robert Neveau, 14, of Lansing, on. Gifts and awards were also given to Other top finishers were Paul Wood, 14, During an awards program at Rodney the other top 14 winners at the program. life of Fowler boy of St Johns; Marc Hufnagel, 15, of St. B. Wilson Junior High School after it was Johns; Jeff Paradise, 12, of St, Johns; all over, Droste earned a big kiss from F O W L E R—Rodney Allen Rademacher, Ralph Witgen, 13, of Westphalia; Joe Fern- Ginger Ann Meyer, 1970 Miss Michigan. -

From William Golding's Lord of the Flies to ABC's LOST. By

Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou A dissertation to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki September 2013 Humanity Square One: From William Golding’s Lord of the Flies to ABC’s LOST. by Antonia Iliadou Has been approved September 2013 APPROVED: _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ Supervisory Committee ACCEPTED: _______________ Department Chairperson Iliadou 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................1 ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: William Golding’s Lord of the Flies: Analysis and Contextualization ..............1 1.1. a. Lord of the Flies in an age of ambiguity: The position of Golding’s novel in the Post War United States...........................................................................................................2 1.1. b. The Impact of Golding’s Lord of the Flies on its Readers........................................14 1.2. “… The picture of man, at once heroic and sick”: The Depiction -

WILLIAM FAULKNER, Shall Not Perish

WILLIAM FAULKNER Shall Not Perish WHEN THE MESSAGE came about Pete, Father and I had already gone to the field. Mother got it out of the mailbox after we left and brought it down to the fence, and she already knew beforehand what it was because she didn't even have on her sunbonnet, so she must have been watching from the kitchen window when the carrier drove up. And I already knew what was in it too. Because she didn't speak. She just stood at the fence with the little pale envelope that didn't even need a stamp on it in her hand, and it was me that hollered at Father, from further away across the field than he was, so that he reached the fence first where Mother waited even though I was already running. "I know what it is," Mother said. "But can't open it. Open it." "No it ain't!" I hollered, running. "No it ain't!" Then I was hollering, "No, Pete! No, Pete!" Then I was hollering, "God damn them Japs! God damn them Japs!" and then I was the one Father had to grab and hold, trying to hold me, having to wrastle with me like I was another man instead of just nine. And that was all. One day there was Pearl Harbor. And the next week Pete went to Memphis, to join the army and go there and help them; and one morning Mother stood at the field fence with a little scrap of paper not even big enough to start a fire with, that didn't even need a stamp on the envelope, saying, A ship was. -

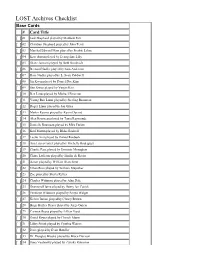

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

Precinct 2 Crime Rate Drops Sharply District Director of Athletics, Has Died

Voice of Community-Minded People since 1976 December 12, 2013 Email: [email protected] www.southbeltleader.com Vol. 38, No. 45 Linda Stephens dies Linda Stephens, wife of Mike Stephens, former Dobie High School varsity football head coach and Pasadena Independent School Precinct 2 crime rate drops sharply District director of athletics, has died. The 65-year-old Stephens, who had battled The local contract patrol of the Harris Coun- year. was 15 – nearly twice the number. of reported criminal mischief cases was eight lupus for the past 20 years or so, died from ty Precinct 2 Constable’s offi ce has reported a The total number of home burglaries report- As with this year, three of those took place in (three in apartment complexes) compared to last complications of the illness Dec. 9 near the marked decrease in area crime for the past month ed for November through early December was apartment complexes, and one arrest was made. year’s 14 (two in apartment complexes) – a de- Stephens’ home in Willow Park, Texas. when compared to last year’s fi gures. eight, three of which took place in apartment There was only one vehicle burglary reported crease of nearly 50 percent. Born on Oct. 28, 1948, Linda wed Mike in According to Sgt. Mike Kritzler, the three complexes. this year between November and early Decem- December’s statistics got off to a bad start 1972. While Mike made various head coach- most frequent crimes this time of year are home At press time, one arrest had been made. ber. -

Armed Forces Day 2002

Memorial Day 2019 (Greetings) In quiet services across our country today, we come together as a nation to remember those lost in the clash of battle; the thunder of bombs, the roar of tanks, the rumbling of airplanes flying overhead and the scream of artillery shells. This Memorial Day, we come together to appreciate the freedom that we enjoy today as we honor the sacrifices that paid for it. As we enjoy living in the land of the free, and the home of the brave, we must continue to remind Americans that there is no freedom without bravery, and those we honor today were brave when it counted the most. Amid the war-torn decades we’ve endured, we can take great pride in these heroes … these men and women who believe they were just doing their duty. They had strength when the situation demanded it; determination when everything felt lost; and devotion, courage and patriotism when others looked to them for guidance. No one ordered them to practice the most basic of human ideals … they did it because they were Americans and because we live in a nation worth defending. Generation after generation, our nation has been lucky enough to have service members who continue to believe 2 | Page that freedom is worth fighting for and, if necessary, dying for. In cemeteries across America and around the world today, people will pause to spread flowers on the graves of those lost in war. But today … Memorial Day … isn’t about the number killed, it’s not about the sorrow we feel at their loss, and it’s not about mourning; what it is about was best expressed by General George S. -

Estancia News-Herald, 05-16-1918 J

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Estancia News, 1904-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 5-16-1918 Estancia News-Herald, 05-16-1918 J. A. Constant Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/estancia_news Recommended Citation Constant, J. A.. "Estancia News-Herald, 05-16-1918." (1918). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/estancia_news/322 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Estancia News, 1904-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTANCIA NEWS-HERAL- D Noi EütabH!iclt9(H Estancia, Torrance County, May 16, 1918 H irsld ÜBtHbllehed i08 New Mexico, Thursday, Volume XIV No. 30 THEM ORITUARY SOLDIERS GALLED GIVE . Help Us Support GOOD SENDOFF Again the ebon enemy, whose Following is a list of the men presence is never welcome and called by the local board to leave of Es- whose visits we so much dread, To the Patriotic citizens has for training camp on May 25. tancia: Notwithstanding that crowded himself into our The Greatest Mother in the World They will go to Camp Cody, largest, prettiest midst, taken the wife and moth- we have the er from a happy home, New Mexico. and best town in the county leaving Wil- - proven by the husband and children noth Robert Cullom Thomas, which has been the ing lard, quota that was given us for the but memories and the vacant Carlos Gomez, Mountainair. Liberty Loan which we chair. -

May Eagle-Color For

Inside Veteran SMDC- Deployed pilot reflects on RDA gets has North The Kwajalein new Alabama service, boss, roots, Eagle page 10 page 4 page 13 The Eagle United States Army Space and Missile Defense Command Volume 11, Number 5, May 2004 Army major joins class of astronaut candidates PETERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Colo. — Another soldier joined the ranks of NASA astronauts and the Army Astronaut Detachment May 6. Maj. Robert S. Kimbrough is among 14 individuals — three Japanese, four military and seven civilians — who were announced as the 2004 class of astronaut candidates during Space Day celebration at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va. “Service to this nation has always been important to me,” Maj. Shane Kimbrough said Kimbrough, who has been a space operations officer at the detachment since 2002. “The benefits to society as a result of NASA’s discoveries are phenomenal. That’s what motivated me to want to work here. I’m very honored and happy to represent the Army in this capacity.” The detachment — an element of the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command in Colorado Springs, Colo., — includes six active-duty Army astronauts and is located at the Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas. Three of these Army astronauts have already flown aboard space shuttle missions. “Those Army Astronauts who have gone Photo by Jan Waddell before me are obviously outstanding — so I’ve got big shoes to fill, but I’m just Celebrating Earth Day honored to be associated with this right now,” said the 36-year old Army pilot. -

Finding Dimensions for Queries∗

Finding Dimensions for Queries∗ Zhicheng Dou1, Sha Hu2, Yulong Luo3, Ruihua Song1, and Ji-Rong Wen1 1Microsoft Research Asia; 2Renmin University of China; 3Shanghai Jiaotong University 1{zhichdou, rsong, jrwen}@microsoft.com; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT dimensions cover the knowledge about watches in five unique We address the problem of finding multiple groups of words aspects, including brands, gender categories, supporting fea- or phrases that explain the underlying query facets, which tures, styles, and colors. The query “visit Beijing” has a di- we refer to as query dimensions. We assume that the impor- mension about popular resorts in Beijing (tiananmen square, tant aspects of a query are usually presented and repeated in forbidden city, summer palace, ...) and a dimension on sev- the query’s top retrieved documents in the style of lists, and eral travel related topics (attractions, shopping, dining, ...). query dimensions can be mined out by aggregating these sig- Query dimensions provide interesting and useful knowl- nificant lists. Experimental results show that a large number edge about a query and thus can be used to improve search of lists do exist in the top results, and query dimensions gen- experiences in many ways. First, we can display query di- erated by grouping these lists are useful for users to learn mensions together with the original search results in an ap- interesting knowledge about the queries. propriate way. Thus, users can understand some important facets of a query without browsing tens of pages. For ex- ample, a user could learn different brands and categories of Categories and Subject Descriptors watches. -

美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 the Vocabulary Coverage in American

國立臺灣師範大學英語學系 碩 士 論 文 Master’s Thesis Department of English National Taiwan Normal University 美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 The Vocabulary Coverage in American Television Programs A Corpus-Based Study 指導教授:陳 浩 然 Advisor: Dr. Hao-Jan Chen 研 究 生:周 揚 亭 Yang-Ting Chou 中 華 民 國一百零三年七月 July, 2014 國 立 英 臺 語 灣 師 學 範 系 大 學 103 碩 士 論 文 美 國 影 集 的 字 彙 涵 蓋 量 語 料 庫 分 析 周 揚 亭 中文摘要 身在英語被視為外國語文的環境中,英語學習者很難擁有豐富的目標語言環 境。電視影集因結合語言閱讀與聽力,對英語學習者來說是一種充滿動機的學習 資源,然而少有研究將電視影集視為道地的語言學習教材。許多研究指出媒體素 材有很大的潛力能激發字彙學習,研究者很好奇學習者要學習多少字彙量才能理 解電視影集的內容。 本研究探討理解道地的美國電視影集需要多少字彙涵蓋量 (vocabulary coverage)。研究主要目的為:(1)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,分別需要 英國國家語料庫彙編而成的字族表(the BNC word lists)和匯編英國國家語料庫 (BNC)與美國當代英語語料庫(COCA)的字族表多少的字彙量;(2)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,不同的電視影集類型需要的字彙量;(3)分析出現在美國 影集卻未列在字族表的字彙,並比較兩個字族表(the BNC word lists and the BNC/COCA word lists)的異同。 研究者蒐集六十部美國影集,包含 7,279 集,31,323,019 字,並運用 Range 分析理解美國影集需要分別兩個字族表的字彙量。透過語料庫的分析,本研究進 一步比較兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。 研究結果顯示,加上專有名詞(proper nouns)和邊際詞彙(marginal words),英 國國家語料庫字族表需 2,000 至 7,000 字族(word family),以達到 95%的字彙涵 蓋量;至於英國國家語料庫加上美國當代英語語料庫則需 2,000 至 6,000 字族。 i 若須達到 98%的字彙涵蓋量,兩個字族表都需要 5,000 以上的字族。 第二,有研究表示,適當的文本理解需要 95%的字彙涵蓋量 (Laufer, 1989; Rodgers & Webb, 2011; Webb, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Webb & Rodgers, 2010a, 2010b),為達 95%的字彙涵蓋量,本研究指出連續劇情類(serial drama)和連續超 自然劇情類(serial supernatural drama)需要的字彙量最少;程序類(procedurals)和連 續醫學劇情類(serial medical drama)最具有挑戰性,因為所需的字彙量最多;而情 境喜劇(sitcoms)所需的字彙量差異最大。 第三,美國影集內出現卻未列在字族表的字會大致上可分為四種:(1)專有 名詞;(2)邊際詞彙;(3)顯而易見的混合字(compounds);(4)縮寫。這兩個字族表 基本上包含完整的字彙,但是本研究顯示語言字彙不斷的更新,新的造字像是臉 書(Facebook)並沒有被列在字族表。 本研究也整理出兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。為達 95%字彙涵 蓋量,英國國家語料庫的 4,000 字族加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識才足夠;而 英國國家語料庫合併美國當代英語語料庫加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識只需 3,000 字族即可達到 95%字彙涵蓋量。另外,為達 98%字彙涵蓋量,兩個語料庫 合併的字族表加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識需要 10,000 字族;英國國家語料 庫字族表則無法提供足以理解 98%美國影集的字彙量。 本研究結果顯示,為了能夠適當的理解美國影集內容,3,000 字族加上專有 名詞和邊際詞彙的知識是必要的。字彙涵蓋量為理解美國影集的重要指標之一, ii 而且字彙涵蓋量能協助挑選適合學習者的教材,以達到更有效的電視影集語言教 學。 關鍵字:字彙涵蓋量、語料庫分析、第二語言字彙學習、美國電視影集 iii ABSTRACT In EFL context, learners of English are hardly exposed to ample language input. -

Common Valor

Common Valor Part II By Leif HerrGesell, Town Historian Men from all walks of life and trades responded to the call for men to serve in the Union Armies of the Civil War. Enlisting in Regiments raised in their local cities and towns, boys barely 18, middle aged farmers and everyone in between volunteered to serve the cause of Union and ultimately to abolish once and for all, legalized, human chattel slavery. In part one of this article we introduced the causes and conditions that lead three young men, from the southern boundary of Canandaigua with South Bristol, to enlist in the Union Army. Charles Housel and his cousin Chas. Sanford from the hamlet of Academy enlisted in 1862 and Joseph Housel Jr., younger brother of Charles, joined them in1864. Joe Housel, Sanford and a neighbor, Gould Benedict all served in the 4th NY Heavy Artillery, Charles Housel was a sergeant in the 148th NY Volunteer Infantry. The Housel/Sanford family was patriotic, as so many post-colonial families were. Grandfather Jasper was already nearing middle age when he had served in The War of 1812. Certainly stories of the Revolution and the War of 1812 were told in the fields while taking lunch under the nooning tree and at the hearth in the evening. In school children were educated in the deeds of their recent ancestors in founding and guarding a new nation. Chas. Sanford, Joseph Housel Jr. and elder brother Charles, surely understood in their minds that it was their duty to preserve the Union of States that their grandfathers had protected, and to end the tyranny of slavery.