Rubens Met.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

Madness and Gender in Late-Medieval English Literature

Durham E-Theses Madness and Gender in Late-Medieval English Literature JOSE, LAURA How to cite: JOSE, LAURA (2010) Madness and Gender in Late-Medieval English Literature, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/217/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 1 Laura Jose “Madness and Gender in Late-Medieval Literature” This thesis discusses presentations of madness in medieval literature, and the ways in which these presentations are affected by (and effect) ideas of gender. It includes a discussion of madness as it is commonly presented in classical literature and medical texts, as well as an examination of demonic possession (which shares many of the same characteristics of madness) in medieval exempla. These chapters are followed by a detailed look at the uses of madness in Malory‟s Morte Darthur, Gower‟s Confessio Amantis, and in two autobiographical accounts of madness, the Book of Margery Kempe and Hoccleve‟s Series. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

The Abuse of Patriarchal Power in Rome: the Rape Narratives of Ovid’S Metamorphoses

The Abuse of Patriarchal Power in Rome: The Rape Narratives of Ovid’s Metamorphoses A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Classics By K. Tinkler Classics Department University of Canterbury 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Abstract……………….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER ONE: Gender in Rome………………………………………………………………………………………. 12 A Woman’s Place in a Man’s World: Patriarchy in Rome…………………………………………………… 12 Lucretia’s Legacy: The Cultural Template of the Raped Woman……………………………………….. 18 The Intimacy of Rape: The Body of a Woman in Antiquity…………………………………………………. 22 CHAPTER TWO: Rape in the Metamorphoses…………………………………………………………………… 29 The Rape Stories of the Metamorphoses………………………………………………………………………….. 29 The Characteristics of Ovid’s Perpetrators………………………………………………………………………… 30 Gods and Non-Human Perpetrators………………………………………………………………………………….. 34 The Characteristics of Ovid’s Victims…………………………………………………………………………………. 40 The Rape of Philomela………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 44 The Male Gaze………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 48 CHAPTER THREE: The Aftermath of Rape…………………………………………………………………………. 55 The Non-Metamorphic Consequences………………………………………………………………………………. 55 The Psychological Effect on the Victim……………………………………………………………………………… 60 The Eternal Link between the Victim and the Rapist…………………………………………………………. 63 The Second Rape: The Goddesses’ Wrath…………………………………………………………………………. -

TSJCL Mythology

CONTEST CODE: 09 2012 TEXAS STATE JUNIOR CLASSICAL LEAGUE MYTHOLOGY TEST DIRECTIONS: Please mark the letter of the correct answer on your scantron answer sheet. 1. The myrtle and the dove are her symbols (A) Amphitrite (B) Aphrodite (C) Artemis (D) Athena 2. His wife left him and ran off to Troy with Paris; he was not happy about it and got some help (A) Agamemnon (B) Diomedes (C) Menelaus (D) Odysseus 3. This deity was the only one who worked; god of the Forge and Blacksmiths (A) Apollo (B) Hephaestus (C) Mercury (D) Neptune 4. He went searching for a bride and found Persephone (A) Aeacus (B) Hades (C) Poseidon (D) Vulcan 5. Half man, half goat, he was the patron of shepherds (A) Aeolus (B) Morpheus (C) Pan (D) Triton 6. He attempted to win the contest as Patron of Athens, but lost to Athena (A) Apollo (B) Hephaestus (C) Hermes (D) Poseidon 7. He performs Twelve Labors for his cousin as penance for crimes committed while mad (A) Aegeus (B) Heracles (C) Jason (D) Theseus 8. As punishment for opposing Zeus, he holds the Heavens on his shoulders (A) Atlas (B) Epimetheus (C) Oceanus (D) Prometheus 9. Son of Zeus, king of Crete, he ordered the Labyrinth built to house the Minotaur (A) Alpheus (B) Enipeus (C) Minos (D) Peleus 10. This wise centaur taught many heroes, including Achilles (A) Chiron (B) Eurytion (C) Nessus (D) Pholus 11. She was the Muse of Comedy (A) Amphitrite (B) Euphrosyne (C) Macaria (D) Thalia 12. She rode a white bull from her homeland to Crete and bore Zeus three sons (A) Danae (B) Europa (C) Leda (D) Semele 13. -

Homeric Catalogues Between Tradition and Invention

31 DOI:10.34616/QO.2019.4.31.54 Quaestiones Oralitatis IV (2018/2019) Isabella Nova Università Cattolica di Milano [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-7880-4856 HOMERIC CATALOGUES BETWEEN TRADITION AND INVENTION Abstract This contribution aims at showing how a traditional list of names could be varied by poets with the addition of new ones sharing the same features, with a special focus on the Nereids’ names. A compari- son between the catalogue of Nereids in the Iliad (XVIII 39–49) and the one in the Theogony (Theog. 243–264) shows that whilst some names are traditional and some others seem to be invented ad hoc, they all convey relaxing images (sea, nature, beauty, or gifts for sailors). This list of names did not become a fixed one in later times either: inscriptions on vase-paintings of the 5th century preserve names different than the epic ones. Even Apollodorus (I 2, 7) gives a catalogue of Nereids derived partly from the Iliad and partly from the Theogony, with the addition of some names belonging to another group of deities (the Oceanids) and other forms unattested elsewhere but with the same features of the epic ones. A further comparison between a catalogue of Nymphs in the Georgics (IV 333–356) and its reception in the work of Higynus proves that adding new names to a traditional list is a feature not only of oral epic poetry, but also of catalogues composed in a literate culture. Keywords: Homer, Iliad, Hesiod, Theogony, Apollodorus, Virgil, Hyginus, reception of Homer, vase-paintings, catalogues, Nereids, speaking-names, oral culture, orality 32 Isabella Nova This paper will consider the ancient lists of the Nereids’ names, making a comparison between catalogues in epic po- etry, which were orally composed, and their reception in clas- sical times. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Order Number 8726644 The relationship of love and death: Metaphor as a unifying device in the Elegies of Propertius Gruber, John Charles, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Gruber, John Charles. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zecb Rd. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

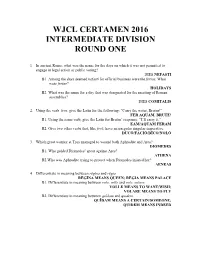

Wjcl Certamen 2016 Intermediate Division Round One

WJCL CERTAMEN 2016 INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. In ancient Rome, what was the name for the days on which it was not permitted to engage in legal action or public voting? DIES NEFASTI B1. Among the days deemed nefasti for official business were the feriae. What were feriae? HOLIDAYS B2. What was the name for a day that was designated for the meeting of Roman assemblies? DIES COMITALIS 2. Using the verb fero, give the Latin for the following: “Carry the water, Brutus!” FER AQUAM, BRUTE! B1. Using the same verb, give the Latin for Brutus’ response: “I’ll carry it.” EAM/AQUAM FERAM B2. Give two other verbs that, like ferō, have an irregular singular imperative. DUCŌ/FACIŌ/DĪCO/NOLŌ 3. Which great warrior at Troy managed to wound both Aphrodite and Ares? DIOMEDES B1. Who guided Diomedes’ spear against Ares? ATHENA B2.Who was Aphrodite trying to protect when Diomedes injured her? AENEAS 4. Differentiate in meaning between rēgīna and rēgia. RĒGĪNA MEANS QUEEN; RĒGIA MEANS PALACE B1. Differentiate in meaning between volo, velle and volo, volare. VOLLE MEANS TO WANT/WISH; VOLARE MEANS TO FLY B2. Differentiate in meaning between quīdam and quidem. QUĪDAM MEANS A CERTAIN/SOMEONE; QUIDEM MEANS INDEED 5. Translate the following sentence into Latin: “I was sleeping under the tree.” DORMIĒBAM SUB ARBORE B1. Translate the following sentence into Latin: “Who spoke before you?” QUIS ANTE TĒ DĪXIT/DICĒBAT B2. Translate the following sentence into Latin using a participle: “I hear you singing.” AUDIŌ TĒ CANENTEM/CANTANTEM 6. At which battle of 202 BCE did Scipio Africanus achieve final victory over Hannibal, bringing an end to the Second Punic War? ZAMA B1. -

Spices in Greek Mythology Marcel Detienne

EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE HUMAN SCIENCES General Editor: John Mepham This is a new series of translations of important and influential works of European thought in the fields of philosophy and the human sciences. Other titles in the series: Sartre and Marxism Pietro Chiodi Society Against Nature Serge Moscovici SPICES IN GREEK The Human History of Nature MYTHOLOGY Serge Moscovici Galileo Studies Alexandre Koyrt MARCEL DETIENNE Translated from the French by JANET LLOYD With an introduction by J. -P. VERNANT Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, Contents New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex Copyright O 1972 in France as Les jardins d'Adonis by Gallimard Edition; English translation by Janet Lloyd 0 1977 by the Harvester Press, Limitcd. Afterword to the 1985 printing of the French edition is copyright 0 1985 Gallirnard, and is translated into English for Princeton University Press by Froma I. Zeitlin. Afterword translation Introdu~tzonby Jean-Plerre Vernant vii Q 1994 Princeton University Press. This publication is by arrangements with Editions Gallimard and Simon & Schuster, Ltd. Translator's Note xli All Rights Reserved Foreword 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chapter 1 The Perfumes of Arabia Detienne, Marcel. [Jardins d'Adonis. English] Chapter 2 The Spice Ox The gardens of Adonis: spices in Greek mythology I Marcel Chapter 3 From Myrrh to Lettuce Detienne; translated from the French by Janet Lloyd; with an introduction by 1.-P. Vernant. Chapter 4 The Misfortunes of Mint p. cm.-(Mythos: the PrincetoniBollingen series in world mythology) Chapter 5 The Seed of Adonis Originally published: Hassocks: Harvester Press, 1977. -

Tooke's Pantheon of the Heathen Gods and Illustrious Heroes

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com -- - __ |- · |- |- |- |-|--. -:|-· |.…….….….….---- |-· |-|- ·|- ·· · · |-··|- |- |-· |-- |-· |- |- .|- ·|-|-|- | | . .|-|- |- ·-|- · - |×· . |(-)|-|- |- |-|- |- ſ. |- ·-|- |- |-|-|-|- · . · ·|× ·· |-|× |-|-|- · -· |-- |-|- |- |- . |- |- |- -|- |- |- · |- · |- ·-. |- |- ·|- |- |-|-|- ·|- ·· : - · |- ··|-|- |-·|- |- ·|-· |-|- |- |- |- · |- |- |-· |- · ·|-- |-· ·|- |- | .|- |- |- |- |- ·|- · |- |-|- ----· | .|- : · |-|- -- · _ |-├. |- ---- ·:·| |- ·|- |-·|- .- . |-· -.-|-|- |- |- |-- · ·-· )·---- · ·-·|-----· · |-|------ - |- --------|- . | _|- - . -- |-|- . .- -- | _ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARY - º \ , º, y " . * , an TookE's PANTHEON ... , - 2. * , , *... * * * * - , , , , r . of ºpe > * > 2 -> • * * * * * > > → * HEATHEN Gods 3 2 * AND I L II, U S T R I O U S HE R O E. S. REVISED FOR * A CLASSICAL COURSE OF EDUCATION, AND ADAPTED FOR THE USE OF STUDENTS OF EVERY AGE AND OF EITHER SEX. illustrateD WITH ENGRAVINGS FROM NEW AND ORIGINAL DESIGrºg. * º * - * -- B. A. L TIM OR E: PUBLISHED BY WILLIAM & JOSEPH NEAL. 1838, - DISTRICT OF MARYLAND, ss. - BE IT REMEMBERED, that on this fifth day of May, in the forty-first year of the Independence of the United States of America, Edward J. Coale and Nathaniel G. Maxwell, of the said district, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as proprietors in the words -

The Metamorphic Tragedy of Anthony and Cleopatra AN1HONY MIILER

SYDNEY STUDIES The Metamorphic Tragedy of Anthony and Cleopatra AN1HONY MIILER When he turned the pages of Plutarch, his principal historical source for Anthony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare was confronted with the values of a sober ethical arbiter. Plutarch treats Anthony's tragic fall as the consequence of his subservience to fleshly pleasure. Such pleasure is a 'pestilent plague and mischief', a 'sweet poison'. It makes mature manhood regress to childishness: Anthony 'spent and lost in childish sports (as a man might say) and idle pastimes, the most precious thing a man can spend, ... and that is, time'. Even more shamefully, it makes courageous manhood descend to cowardliness. By his flight at the battle ofActium, Anthony 'had not only lost the courage and heart ofan Emperor, but also ofa valiant man.... In the end, as Paris fled from the battle and went to hide himself in Helen's arms, even so did he in Cleopatra's arms'.l Yet Shakespeare's management of his tragedy, like his understanding of Roman history in general, is not circumscribed by Plutarch. There are indications that Shakespeare looked far afield to furnish his play with quite minor details, such as Anthony's account ofEgyptian farming practices, which apparently derives from Pliny or from the Renaissance historian of Africa, Johannes Leo. The play's treatment of the historical significance of Augustus Caesar's victory over Anthony and Cleopatra derives not only from Plutarch, but from the Augustan poets Horace and VirgiI.2 In dramatizing the tragedy ofAnthony, and in amplifying it with the tragedy of Cleopatra, Shakespeare voices not only Plutarchan censoriousness. -

HESIOD in OVID: the METAMORPHOSIS of the CATALOGUE of WOMEN a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Co

HESIOD IN OVID: THE METAMORPHOSIS OF THE CATALOGUE OF WOMEN A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ioannis V. Ziogas February 2010 © 2010 Ioannis V. Ziogas HESIOD IN OVID: THE METAMORPHOSIS OF THE CATALOGUE OF WOMEN Ioannis V. Ziogas, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2010 The subject of my dissertation is Ovid's intertextual engagement with the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women (aka the Ehoiai). I examine the Hesiodic character of Ovid’s work, focusing mainly on the Metamorphoses and Heroides 16-17. The Metamorphoses begins with Chaos and moves on to the loves of the gods, reiterating the transition from the Theogony to the Catalogue. Divine passions for beautiful maidens constitute a recurring motif in the Metamorphoses, establishing the importance of the erotic element in Ovid’s hexameter poem and referring to the main topic of the Ehoiai (fr. 1.1-5 M-W). The first five books of Ovid’s epic follow the descendants of the river-god Inachus, beginning with Jupiter’s rape of Io and reaching forward to Perseus, and the stemma of the Inachids features prominently in the Hesiodic Catalogue (fr. 122-59 M-W). As a whole, the Metamorphoses delineates the genealogies of the major Greek tribes (Inachids, Thebans, Athenians), and includes the Trojans, the only non-Greek genealogies of the Catalogue, which were dealt with in the last part of Hesiod’s work. Ovid’s foray into the Hesiodic corpus gives us a new perspective to interpreting his aemulatio of Vergil.