Second Issue of Rediscovering China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chinese Civil War (1927–37 and 1946–49)

13 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 2: THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR (1927–37 AND 1946–49) As you read this chapter you need to focus on the following essay questions: • Analyze the causes of the Chinese Civil War. • To what extent was the communist victory in China due to the use of guerrilla warfare? • In what ways was the Chinese Civil War a revolutionary war? For the first half of the 20th century, China faced political chaos. Following a revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Manchu dynasty, the new Republic failed to take hold and China continued to be exploited by foreign powers, lacking any strong central government. The Chinese Civil War was an attempt by two ideologically opposed forces – the nationalists and the communists – to see who would ultimately be able to restore order and regain central control over China. The struggle between these two forces, which officially started in 1927, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, but started again in 1946 once the war with Japan was over. The results of this war were to have a major effect not just on China itself, but also on the international stage. Mao Zedong, the communist Timeline of events – 1911–27 victor of the Chinese Civil War. 1911 Double Tenth Revolution and establishment of the Chinese Republic 1912 Dr Sun Yixian becomes Provisional President of the Republic. Guomindang (GMD) formed and wins majority in parliament. Sun resigns and Yuan Shikai declared provisional president 1915 Japan’s Twenty-One Demands. Yuan attempts to become Emperor 1916 Yuan dies/warlord era begins 1917 Sun attempts to set up republic in Guangzhou. -

January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu Citation: “Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu,” January 14, 1950, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi, ed., Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao (Mao Zedong’s Manuscripts since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China), vol. 1 (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1987), 237; translation from Shuguang Zhang and Jian Chen, eds.,Chinese Communist Foreign Policy and the Cold War in Asia: New Documentary Evidence, 1944-1950 (Chicago: Imprint Publications, 1996), 137. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112672 Summary: Mao Zedong gives instructions to Hu Qiaomu on how to write about recent developments within the Japanese Communist Party. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document [...] Comrade [Hu] Qiaomu: I shall leave for Leningrad today at 9:00 p.m. and will not be back for three days. I have not yet received the draft of the Renmin ribao ["People's Daily"] editorial and the resolution of the Japanese Communist Party's Politburo. If you prefer to let me read them, I will not be able to give you my response until the 17th. You may prefer to publish the editorial after Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi has read them. Out party should express its opinion by supporting the Cominform bulletin's criticism of Nosaka and addressing our disappointment over the Japanese Communist Party Politburo's failure to accept the criticism. It is hoped that the Japanese Communist Party will take appropriate steps to correct Nosaka's mistakes. -

“Little Tibet” with “Little Mecca”: Religion, Ethnicity and Social Change on the Sino-Tibetan Borderland (China)

“LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yinong Zhang August 2009 © 2009 Yinong Zhang “LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) Yinong Zhang, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 This dissertation examines the complexity of religious and ethnic diversity in the context of contemporary China. Based on my two years of ethnographic fieldwork in Taktsang Lhamo (Ch: Langmusi) of southern Gansu province, I investigate the ethnic and religious revival since the Chinese political relaxation in the 1980s in two local communities: one is the salient Tibetan Buddhist revival represented by the rebuilding of the local monastery, the revitalization of religious and folk ceremonies, and the rising attention from the tourists; the other is the almost invisible Islamic revival among the Chinese Muslims (Hui) who have inhabited in this Tibetan land for centuries. Distinctive when compared to their Tibetan counterpart, the most noticeable phenomenon in the local Hui revival is a revitalization of Hui entrepreneurship, which is represented by the dominant Hui restaurants, shops, hotels, and bus lines. As I show in my dissertation both the Tibetan monastic ceremonies and Hui entrepreneurship are the intrinsic part of local ethnoreligious revival. Moreover these seemingly unrelated phenomena are in fact closely related and reflect the modern Chinese nation-building as well as the influences from an increasingly globalized and government directed Chinese market. -

Mao Zedong in Contemporarychinese Official Discourse Andhistory

China Perspectives 2012/2 | 2012 Mao Today: A Political Icon for an Age of Prosperity Mao Zedong in ContemporaryChinese Official Discourse andHistory Arif Dirlik Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5852 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5852 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 4 June 2012 Number of pages: 17-27 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Arif Dirlik, « Mao Zedong in ContemporaryChinese Official Discourse andHistory », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/2 | 2012, Online since 30 June 2015, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5852 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5852 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Mao Zedong in Contemporary Chinese Official Discourse and History ARIF DIRLIK (1) ABSTRACT: Rather than repudiate Mao’s legacy, the post-revolutionary regime in China has sought to recruit him in support of “reform and opening.” Beginning with Deng Xiaoping after 1978, official (2) historiography has drawn a distinction between Mao the Cultural Revolutionary and Mao the architect of “Chinese Marxism” – a Marxism that integrates theory with the circumstances of Chinese society. The essence of the latter is encapsulated in “Mao Zedong Thought,” which is viewed as an expression not just of Mao the individual but of the collective leadership of the Party. In most recent representations, “Chinese Marxism” is viewed as having developed in two phases: New Democracy, which brought the Communist Party to power in 1949, and “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” inaugurated under Deng Xiaoping and developed under his successors, and which represents a further development of Mao Zedong Thought. -

E Virgin Mary and Catholic Identities in Chinese History

e Virgin Mary and Catholic Identities in Chinese History Jeremy Clarke, SJ Hong Kong University Press e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2013 ISBN 978-988-8139-99-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Goodrich Int’l Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents List of illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi Introduction: Chinese Catholic identities in the modern period 1 Part 1 Images of Mary in China before 1842 1. Chinese Christian art during the pre-modern period 15 Katerina Ilioni of Yangzhou 21 Madonna and Guanyin 24 Marian images during the late Ming dynasty 31 e Madonna in Master Cheng’s Ink Garden 37 Marian sodalities 40 João da Rocha and the rosary 42 Part 2 e Chinese Catholic Church since 1842 2. Aer the treaties 51 French Marian devotions 57 e eects of the Chinese Rites Controversy 60 A sense of cultural superiority 69 e inuence of Marian events in Europe 74 3. Our Lady of Donglu 83 Visual inuences on the Donglu portrait 89 Photographs of Cixi 95 Liu Bizhen’s painting 100 4. e rise and fall of the French protectorate 111 Benedict XV and Maximum Illud 118 viii Contents Shanghai Plenary Council, 1924 125 Synodal Commission 132 Part 3 Images of Mary in the early twentieth century 5. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

Church History

GRADE EIGHT CHURCH HISTORY THE JOURNEY OF THE Catholic Church Jesus’ life and mission continue through the Church, the community of believers called by God and empowered by the Holy Spirit to be the sign of the kingdom of God. OBJECTIVES • 4OÏDEEPENÏTHEÏYOUNGÏADOLESCENTSÏKNOWLEDGEÏOFÏTHEÏHISTORYÏOFÏTHEÏ#ATHOLICÏ#HURCH • To lead the young adolescent to a fuller participation in the life and mission of the Church. Grade Eight | Church History 73 I. THE JOURNEY OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH FROM THE TIME OF JESUS TO AD 100 !Ï4HEÏ-ISSIONÏOFÏTHEÏ#HURCH The Church was made manifest to the world on the day of Pentecost by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. [731-32, 737-41, 2623] )MMEDIATELYÏAFTERÏ0ENTECOST ÏTHEÏAPOSTLESÏTRAVELEDÏTHROUGHOUTÏ0ALESTINEÏSPREADINGÏTHEÏh'OODÏ.EWSvÏOFÏ*ESUSÏ life, death, and resurrection to Jews and Gentiles (non-Jews). [767, 849, 858] 3MALLÏGROUPSÏOFÏ*ESUSÏFOLLOWERSÏCONTINUEDÏTOÏGATHERÏTOGETHERÏATÏTHEIRÏLOCALÏSYNAGOGUESÏ4HEYÏALSOÏBEGANÏTOÏ MEETÏINÏEACHÏOTHERSÏHOMESÏFORÏPRAYERÏANDÏhTHEÏBREAKINGÏOFÏTHEÏBREAD vÏ!CTSÏ ÏTHEÏCELEBRATIONÏOFÏTHEÏ%U- charist. [751, 949, 2178, 2624] The apostles James and John were among the leaders of these groups, as were Paul, Barnabas, Titus, and Timo- THYÏ4HEYÏTRAVELEDÏEXTENSIVELY ÏGATHERINGÏFOLLOWERSÏOFÏ*ESUSÏINTOÏSMALLÏCOMMUNITIESÏWHICHÏWEREÏTHEÏBEGINNINGSÏ OFÏLOCALÏCHURCHESÏ4HEÏEARLYÏ#HURCHÏCONSISTEDÏOFÏORDINARYÏMENÏANDÏWOMENÏWHOÏWEREÏSTRENGTHENEDÏBYÏ'ODSÏ Spirit. [777, 797-98, 833, 854, 1229, 1270] 4WOÏGREATÏCONVERTSÏOFÏTHISÏTIMEÏWEREÏ0AUL ÏAÏ*EW ÏTOÏWHOMÏ*ESUSÏREVEALEDÏHIMSELFÏINÏAÏDRAMATICÏWAYÏONÏTHEÏROADÏ -

Pacific Theater of the Cold War 1949 — China Chair: Luyi Peng JHUMUNC 2018

Quadrumvirate: Pacific Theater of the Cold War 1949 — China Chair: Luyi Peng JHUMUNC 2018 Quadrumvirate: Pacific Theater of the Cold War- China Topic A: Defeating the Nationalists and Consolidating a New Communist Government Topic B: Establishing China’s Place as a Regional Power Committee Overview four tools listed in order to promptly implement solutions. It is extremely important to remember It is June 1949, and the withdrawal of the that each and every delegate represents a Japanese after World War II has left the fate of character, or historical individual, rather than a China in the balance. The Chinese Communist specific country. Every directive, communiqué, Party under Mao Zedong has evolved from press release, and portfolio request must disorganized guerrilla militias into an organized accurately reflect the viewpoints of the character. fighting force capable of turning the tide against Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party. The Communist Party must now make the final push Quadrumvirate to gain control of a unified China and defeat the Organization rival Nationalists once and for all. However, even as the end is in sight for a decades-long civil war, China, Japan, South Korea, and USSR will new powers are rising in the region under an even be functioning as a group of four committees, with more precarious conflict: the Cold War. Will interconnected crisis elements, in which all China become one of these new powers, and will debate in the individual committee rooms will it do so with the help of potential Communist impact the other three committees. While there allies in the USSR? Or, as Korea threatens to split are specific concerns that affect each room in half permanently and the Japanese begin to individually and with which delegates must rebuild with the help of the Americans, will the concern themselves, just as important is the new China crack under the pressure of facing too international politicking and debate behind the many rivals at once? Only you, the delegates, will closed doors of the other three committee rooms. -

China's Reforms and International Political Economy

China’s Reforms and International Political Economy International forces shape a state’s domestic development, particularly under globalization. Yet most analysts have ignored the influence of China’s position in the global economy on its economic and political development. Given the deep economic ties between China and the world today, and the state’s increasingly limited capacity to control transnational flows, such a position is difficult to sustain. No single model can explain the relative role of internal and external forces in China’s domestic reforms and international economic policy. Instead this book presents a variety of academic opinions from both main- landers and Western-trained scholars on this issue. These China specialists debate a number of key areas including China’s entry to the WTO and whether state policy or international forces dictate China’s position within the global economy; the role of the local state versus the central state in determining China’s production networks within global manufacturing processes; the question of whether global forces and international organi- zations, such as the WTO, are leading China to adopt conciliatory policies towards both the US and ASEAN, or whether China’s elites still determine the final pattern of trade liberalization and domestic reform? A broad range of case studies supports these areas of investigation, including research on the internationalization of the Chinese state, the opening of the pharma- ceutical sector, the Sino-South Korean ‘‘Garlic War’’ and returnees to China who seek greater economic and social remuneration. Providing vital insights into China’s likely development and international influence in the next decade, China’s Reforms and International Political Economy will appeal to students and scholars of international political economy, China studies and international relations. -

Political Literature and Public Policy in Post-Mao China

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1989 Political literature and public policy in post-Mao China Steve Gideon The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gideon, Steve, "Political literature and public policy in post-Mao China" (1989). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3248. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3248 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF_ MONTANAA DATE : rm POLITICAL LITERATURE AND PUBLIC POLICY IN POST-MAO CHINA By Steve Gideon B.A., University of Montana, 1986 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1989 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Jean, Graduate School AJ !5') I j E f Date UMI Number: EP34343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

New Trends in Mao Literature from China

Kölner China-Studien Online Arbeitspapiere zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas Cologne China Studies Online Working Papers on Chinese Politics, Economy and Society No. 1 / 1995 Thomas Scharping The Man, the Myth, the Message: New Trends in Mao Literature From China Zusammenfassung: Dies ist die erweiterte Fassung eines früher publizierten englischen Aufsatzes. Er untersucht 43 Werke der neueren chinesischen Mao-Literatur aus den frühen 1990er Jahren, die in ihnen enthaltenen Aussagen zur Parteigeschichte und zum Selbstverständnis der heutigen Führung. Neben zahlreichen neuen Informationen über die chinesische Innen- und Außenpolitik, darunter besonders die Kampagnen der Mao-Zeit wie Großer Sprung und Kulturrevolution, vermitteln die Werke wichtige Einblicke in die politische Kultur Chinas. Trotz eindeutigen Versuchen zur Durchsetzung einer einheitlichen nationalen Identität und Geschichtsschreibung bezeugen sie auch die Existenz eines unabhängigen, kritischen Denkens in China. Schlagworte: Mao Zedong, Parteigeschichte, Ideologie, Propaganda, Historiographie, politische Kultur, Großer Sprung, Kulturrevolution Autor: Thomas Scharping ([email protected]) ist Professor für Moderne China-Studien, Lehrstuhl für Neuere Geschichte / Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas, an der Universität Köln. Abstract: This is the enlarged version of an English article published before. It analyzes 43 works of the new Chinese Mao literature from the early 1990s, their revelations of Party history and their clues for the self-image of the present leadership. Besides revealing a wealth of new information on Chinese domestic and foreign policy, in particular on the campaigns of the Mao era like the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution, the works convey important insights into China’s political culture. In spite of the overt attempts at forging a unified national identity and historiography, they also document the existence of independent, critical thought in China. -

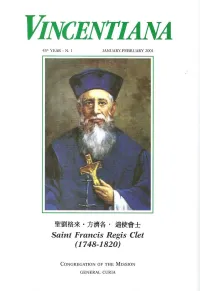

Dates in the Life of Francis Regis Clet

Santa Sede On Wednesday, February 21, 2001, His Holiness Pope John Paul II held, in St. Peter’s Square, an Ordinary Public Consistory for the creation of new cardinals. The Holy Father arrived at the portico of the basilica, where the cardinals were already gathered, at 10:30 a.m. and immediately took his seat. After the liturgical greeting, the Holy Father read the formula for the creation of the cardinals and proclaimed their names, among which was that of Stéphanos II Ghattas, C.M., Patriarch of Alexandria for Copts (Egypt). Then, the first of the cardinals, Giovanni Battista Re, gave a warm greeting of gratitude. After the homily, the Pope conferred the biretta on the new cardinals and assigned to each one his own Title or Deaconry. The ceremony concluded with the apostolic blessing. ****** Cardinal Stéphanos II Ghattas, C.M., Patriarch of Alexandria for Copts (Egypt), was born on January 16, 1920 in Sheikh Zein-el-Dine, eparchy of Sohag of the Copts (Egypt). He entered the minor seminary in Cairo in August 1929 and did his classical studies at the Jesuits’ Holy Family High School. In September 1938, he was sent to the Pontifical Athenaeum “de Propaganda Fide” in Rome where he obtained a doctorate in philosophy and theology. He was ordained to the priesthood in Rome on March 25, 1944. He began his pastoral ministry as a philosophy and dogmatic theology professor at the major seminary in Tahta (Egypt). On October 2, 1952, he entered the Congregation of the Mission and made his novitiate in Paris. After working for six years in Lebanon, he was named econome and then superior of our community in Alexandria.