Women of the South ' in European Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece Vol. 43, 2010 GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE ROCK SLOPE STABILITY PROBLEMS OCCURRED AT THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE COASTAL BYZANTINE WALL OF KAVALA CITY, GREECE Loupasakis C. Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration, Engineering Geology Department Spanou N. Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration, Engineering Geology Department Kanaris D. Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration, Engineering Geology Department Exioglou D. Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration, East Macedonia-Thrace Regional Branch Georgakopoulos A. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Geology, Department of Min eralogyPetrology-Economic Geology, Laboratory of Economic Geology https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11299 Copyright © 2017 C. Loupasakis, N. Spanou, D. Kanaris, D. Exioglou, A. Georgakopoulos To cite this article: Loupasakis, C., Spanou, N., Kanaris, D., Exioglou, D., & Georgakopoulos, A. (2010). GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE ROCK SLOPE STABILITY PROBLEMS OCCURRED AT THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE COASTAL BYZANTINE WALL OF KAVALA CITY, GREECE. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 43(3), 1230-1237. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11299 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 18/02/2021 15:49:19 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 18/02/2021 15:49:19 | Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Patras, May, 2010 GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE ROCK SLOPE STABILITY PROBLEMS OCCURRED AT THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE COASTAL BYZANTINE WALL OF KAVALA CITY, GREECE Loupasakis C.1, Spanou N.2, Kanaris D.3, Exioglou D. -

A New Hydrobiid Species (Caenogastropoda, Truncatelloidea) from Insular Greece

Zoosyst. Evol. 97 (1) 2021, 111–119 | DOI 10.3897/zse.97.60254 A new hydrobiid species (Caenogastropoda, Truncatelloidea) from insular Greece Canella Radea1, Paraskevi Niki Lampri1,3, Konstantinos Bakolitsas2, Aristeidis Parmakelis1 1 Section of Ecology and Systematics, Department of Biology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15784 Panepistimiopolis, Greece 2 High School, Agrinion, 3rd Parodos Kolokotroni 11, 30133 Agrinion, Greece 3 Institute of Marine Biological Resources and Inland Waters, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, 46.7 km of Athens – Sounio ave., 19013 Anavissos Attica, Greece http://zoobank.org/FE7CB458-9459-409C-B254-DA0A1BA65B86 Corresponding author: Canella Radea ([email protected]) Academic editor: T. von Rintelen ♦ Received 1 November 2020 ♦ Accepted 18 January 2021 ♦ Published 5 February 2021 Abstract Daphniola dione sp. nov., a valvatiform hydrobiid gastropod from Western Greece, is described based on conchological, anatomical and molecular data. D. dione is distinguished from the other species of the Greek endemic genus Daphniola by a unique combination of shell and soft body character states and by a 7–13% COI sequence divergence when compared to congeneric species. The only population of D. dione inhabits a cave spring on Lefkada Island, Ionian Sea. Key Words Freshwater diversity, Lefkada Island, taxonomy, valvatiform Hydrobiidae Introduction been described so far. More than 60% of these genera inhabit the freshwater systems of the Balkan Peninsula The Mediterranean Basin numbers among the first 25 (Radea 2018; Boeters et al. 2019; Delicado et al. 2019). Global Biodiversity Hotspots due to its biological and The Mediterranean Basin, the Balkan, the Iberian and ecological biodiversity and the plethora of threatened bi- the Italian Peninsulas seem to be evolutionary centers of ota (Myers et al. -

Elephas Antiquus in Greece: New finds and a Reappraisal of Older Material (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Elephantidae)

Quaternary International xxx (2010) 1e11 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Elephas antiquus in Greece: New finds and a reappraisal of older material (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Elephantidae) Evangelia Tsoukala a,*, Dick Mol b, Spyridoula Pappa a, Evangelos Vlachos a, Wilrie van Logchem c, Markos Vaxevanopoulos d, Jelle Reumer e a Aristotle University, School of Geology, University campus, 54 124 Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece b Natural History Museum Rotterdam and Mammuthus Club International, Gudumholm 41, 2133 HG Hoofddorp, The Netherlands c Mammuthus Club International, Bosuilstraat 12, 4105 WE Culemborg, The Netherlands d Ministry of Culture, Ephorate of Palaeoanthropology-Speleology of Northern Greece, Navarinou 28, 55131, Thessaloniki, Greece e Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University and Natural History Museum Rotterdam, PO Box 23452, 3001 KL Rotterdam, The Netherlands article info abstract Article history: This paper briefly describes some recently discovered remains of the straight-tusked elephant, Elephas Available online xxx antiquus, from Greece. Material of this extinct proboscidean was found in four localities in Northern Greece: Kaloneri and Sotiras in Western Macedonia, Xerias in Eastern Macedonia, and Larissa in Thessaly. In addition, published elephant remains from Ambelia, Petres and Perdikas, also from Northern Greece, are reinterpreted and also attributed to E. antiquus. Of all these, the Kaloneri elephant shows an inter- esting paleopathology: it was disabled by a broken right tusk. Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction of E. namadicus comes from India. Maglio (1973) considered the Asiatic form E. namadicus to be a senior synonym of the European Fossil Proboscidea are known from Neogene and Quaternary form E. -

Estimating Employer Labour-Market Power and Its Wage Effects

Making their own weather? Estimating employer labour-market power and its wage effects∗ Pedro S. Martinsy Queen Mary University of London & NovaSBE & IZA & GLO December 30, 2019 Abstract The subdued wage growth observed over the last years in many countries has spurred renewed interest in monopsony views of the labour market. This paper is one of the first to measure the extent and robustness of employer labour-market power and its wage implications exploiting comprehensive matched employer-employee data. We find average (employment-weighted) Herfindhal indices of 800 to 1,100; and that less than 9% of workers are exposed to concentration levels thought to raise market power concerns. However, these figures can increase significantly with different methodological choices. Finally, when controlling for both worker and firm heterogeneity and instrumenting for concentration, wages are found to be negatively affected by employer concentration, with elasticities of around -1.5%. Keywords: Oligopsony, Wages, Portugal. JEL Codes: J42, J31, J63. ∗The author thanks Andrea Bassanini, Wenjing Duan, Judite Goncalves, Juan Jimeno, Claudio Lucifora, Ioana Marinescu, Bledi Taska and workshop participants at Queen Mary University of London and the Euro- pean Commission for comments. The author also thanks INE and the Ministries of Education and Employment, Portugal, for data access, and the European Union for financial support (grant VS/2016/0340). yEmail: [email protected]. Web: https://sites.google.com/site/pmrsmartins/. Address: School of Business and Management, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, United Kingdom. Phone: +44/0 2078822708. 1 1 Introduction The limited wage growth observed in many countries in the recovery following the 2008 finan- cial crisis has prompted important questions about the degree of wage setting power enjoyed by employers. -

Geological Mapping by the Use of Multispectral and Multitemporal Satellite Images, Compared with GIS Geological Data

Geological mapping by the use of multispectral and multitemporal satellite images, compared with GIS geological data. Case studies from Macedonia area, Northern Greece. Dimitrios Oikonomidis, Antonios Mouratidis, Theodore Astaras and Mihail Niarhos Laboratory of Remote Sensing and GIS Applications, Geology Dept. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece. Lecturer Dimitrios Oikonomidis: [email protected] 1. Location and physical background of the study areas Image processing software: ENVI 4.6. GIS software: ArcGIS 9.3. Two study areas have been selected (Figure 1): Lithological units and faults were digitized from the maps of IGME. After that, 1) Kassandra peninsula, in Halkidiki Prefecture, Macedonia Province, Northern Greece geological maps (simplified lithology and faults) and rose diagrammes were 2) Thassos island, in Kavala Prefecture, Macedonia Province, Northern Greece. constructed (Figures 2-3). Then, certain digital image processing was applied to the satellite images, so that lithological units and photo-lineaments could be extracted. Lithological maps and lineaments’ maps were also produced. Finally, rose-diagrammes were constructed for comparing tectonic data from geological maps and lineaments derived from satellite images. Figure 3. Faults’ rose-diagrammes (azimuth/total length per class): Kassandra peninsula (3a/left) and Thassos island (3b/right). 3. Landsat-7/ETM+ image processing A Landsat-7 ETM+ image contains both multispectral and panchromatic bands with different spatial resolutions (30m and 15m). For this reason, an image sharpening methodology (else called merging or fusion) had to be applied, so that all the bands would have the same pixel size and could be processed easier. There are numerous methodologies for this, such as Principal Components Analysis/PCA sharpening, IHS (or HSV) sharpening Figure 1. -

Zootaxa, Araneae, Zodariidae

Zootaxa 1009: 51–60 (2005) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1009 Copyright © 2005 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Ant-eating spiders (Araneae: Zodariidae) of Portugal: additions to the current knowledge STANO PEKÁR1* & PEDRO CARDOSO2 1 Department of Zoology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, KotláÍská 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Centro de Biologia Ambiental, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Praceta dos Metalúr- gicos, 2, 1º Dto., 2835-043 Baixa da Banheira, Portugal. Present address: Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark * Corresponding author Abstract Three new species of zodariid spiders are described in this paper: Amphiledorus ungoliantae sp. n. and Zodarion bosmansi sp. n. from southern Portugal, and Zodarion atlanticum sp. n. from central Portugal and the Azores. Additional records on another eight taxa from central and southern Portu- gal are given: Amphiledorus adonis, Zodarion alacre, Z. jozefienae, Z. lusitanicum, Z. maculatum, Z. merlijni, Z. styliferum, and Z. styliferum forma extraneum. To date, there are 19 species (plus one form) of zodariid spiders known from Portugal. Key words: Amphiledorus, Zodarion, description, faunistics, distribution, Azores, Iberian Introduction With more than 750 species described so far, the family Zodariidae Thorell 1881 is one of the fifteen most species rich spider families. Representatives of this family are distributed over all continents, except Antarctica. Only four genera, Amphiledorus Jocqué & Bosmans 2001, Palaestina O. P.-Cambridge 1872, Selamia Simon 1873 and Zodarion Walckenaer 1826, with about 80 species occur in Europe. One third of these species is restricted to the Iberian Peninsula (Platnick 2005). -

Forest Fires Distribution in the Continental Area of Kavala

JOURNAL OF Engineering Science and Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Review 9 (1) (2016) 99-102 estr Technology Review J Research Article www.jestr.org Forest Fires Distribution in the Continental Area of Kavala D Filiadis 1Forester MSc, Forest Service of Kavala, Terma Argirokastrou, GR-65404 Kavala, Greece Received 10 April 2016; Accepted 15 May 2016 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The prefecture of Kavala has a long history of devastating forest fire events in both its continental part and Thasos Island. Forest fire records provide useful information on spatial and temporal distribution of forest fire events after statistical analysis. In this case study, the distribution of forest fires in the continental area of Kavala prefecture is presented for the period 2001-2014 through a series of simple-method statistics and charts/graphs. The number of forest fire events and burned area are presented on a month to month and annual basis. Burned forest area is categorized in three types (forest, shrub, meadow) according to Forest Services statistical records. Legislation changes on forest-shrub definition during the aforementioned period, could potentially affect the consistency of forest fire records. Thus spatial imagery was used for a more uniform interpretation of forest-shrub definitions on the forest fire spatial data. The most destructive wildfire years were 2013 and 2001, affected mainly by a respective single large forest fire event. On the opposite 2004, 2005 and 2010 were the least destructive years for the time period studied. Mediterranean type shrub lands were by far the most affected vegetation type that were also affected by the two single large wildfire event in 2001 and 2013. -

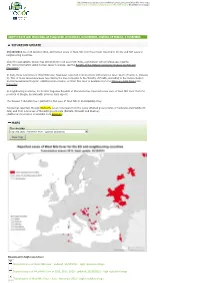

Situation Update Maps

http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/west_nile_fever/West-Nile-fever-maps ECDC Portal > English > Health Topics > West Nile fever > West Nile fever maps NEXT UPDATE AND MAPS WILL BE PUBLISHED ON MONDAY, 5 NOVEMBER, INSTEAD OF FRIDAY, 3 NOVEMBER. SITUATION UPDATE 25/10/2012 As of 25 October 2012, 228 human cases of West Nile fever have been reported in the EU and 547 cases in neighbouring countries. Since the last update, Greece has detected one new case from Pella, a prefecture with previous case reports. (For more information about human cases in Greece, see the Bulletin of the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.) In Italy, three new cases of West Nile fever have been reported from provinces with previous case reports (Treviso 1, Venezia 3). Two of these cases have been reported by the Veneto Region to the Ministry of Health, according to the Veneto Region Special Surveillance Program. (Additional information on West Nile fever is available from the Ministero della Salute and Epicentro) In neighbouring countries, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia has reported a new case of West Nile fever from the province of Skopje, an area with previous case reports. The Russian Federation has reported the first case of West Nile in Stavropolskiy Kray. Tunisia has reported, through EpiSouth, seven new cases from the newly affected governorates of Jendouba and Mahdia (El Jem) and from new areas of Monastir governorate (Bembla, Monastir and Shaline). (Additional information is available from EpiSouth) MAPS Choose map Reported -

Cultura E Jornalismo Cultural: O Caso Do Semanário Região De Leiria

Duarte Nuno Alves Jorge Viseu Covas CULTURA E JORNALISMO CULTURAL: O CASO DO SEMANÁRIO REGIÃO DE LEIRIA Relatório de Estágio em Jornalismo e Comunicação, orientado pelo Doutor José Carlos Santos Camponez e pela Doutora Rita Joana Basílio de Simões, apresentado ao Departamento de Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra Setembro 2017 1 Faculdade de Letras CULTURA E JORNALISMO CULTURAL: O CASO DO SEMANÁRIO REGIÃO DE LEIRIA Ficha Técnica: Tipo de trabalho Relatório de estágio Título CULTURA E JORNALISMO CULTURAL: O CASO DO SEMANÁRIO REGIÃO DE LEIRIA Autor/a Duarte Nuno Alves Jorge Viseu Covas Orientador/a José Carlos dos Santos Camponez Coorientador/a Rita Joana Basílio de Simões Júri Presidente: Doutor João José Figueira da Silva Vogais: 1. Doutor João Manuel dos Santos Miranda 2. Doutora Rita Joana Basílio de Simões Identificação do Curso 2º Ciclo em Jornalismo e Comunicação Área científica Ciências da Comunicação Especialidade/Ramo Cultura e Jornalismo Cultural Data da defesa 25-10-2017 Classificação 16 valores A cultura assusta muito. É uma coisa apavorante para os ditadores. Um povo que lê nunca será um povo de escravos. António Lobo Antunes ii AGRADECIMENTOS À minha família, por tudo; Ao professor doutor José Carlos Santos Camponez e à professora doutora Rita Basílio de Simões, pela orientação e disponibilidade; À Universidade de Coimbra e ao seu ex-libris, a Faculdade de Letras, pelo acolhimento; A todos os docentes que fizeram parte do meu percurso académico como estudante de Jornalismo e Comunicação, pelos ensinamentos; Aos trabalhadores do semanário Região de Leiria, em especial ao meu orientador de estágio Manuel Leiria, pela atenção, paciência e ajuda; Aos meus amigos André Moreira, Gonçalo Barreto, João Pimenta, Mílton Vogado, Mónica Marques, Nuno Moura, Pedro Abrantes, Renato Travassos e Sílvia Santos, pelas reminiscências. -

Selido3 Part 1

ΔΕΛΤΙΟ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΚΗΣ ΕΤΑΙΡΙΑΣ Τόμος XLIII, Νο 3 BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF GREECE Volume XLIII, Νο 3 1 (3) ΕΙΚΟΝΑ ΕΞΩΦΥΛΛΟΥ - COVER PAGE Γενική άποψη της γέφυρας Ρίου-Αντιρρίου. Οι πυλώνες της γέφυρας διασκοπήθηκαν γεωφυ- σικά με χρήση ηχοβολιστή πλευρικής σάρωσης (EG&G 4100P και EG&G 272TD) με σκοπό την αποτύπωση του πυθμένα στην περιοχή του έργου, όσο και των βάθρων των πυλώνων. (Εργα- στήριο Θαλάσσιας Γεωλογίας & Φυσικής Ωκεανογραφίας, Πανεπιστήμιο Πατρών. Συλλογή και επεξεργασία: Δ.Χριστοδούλου, Η. Φακίρης). General view of the Rion-Antirion bridge, from a marine geophysical survey conducted by side scan sonar (EG&G 4100P and EG&G 272TD) in order to map the seafloor at the site of the construction (py- lons and piers) (Gallery of the Laboratory of Marine Geology and Physical Oceanography, University of Patras. Data acquisition and Processing: D. Christodoulou, E. Fakiris). ΔΕΛΤΙΟ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΚΗΣ ΕΤΑΙΡΙΑΣ Τόμος XLIII, Νο 3 BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF GREECE Volume XLIII, Νο 3 12o ΔΙΕΘΝΕΣ ΣΥΝΕΔΡΙΟ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΚΗΣ ΕΤΑΙΡΙΑΣ ΠΛΑΝHΤΗΣ ΓH: Γεωλογικές Διεργασίες και Βιώσιμη Ανάπτυξη 12th INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF GREECE PLANET EARTH: Geological Processes and Sustainable Development ΠΑΤΡΑ / PATRAS 2010 ISSN 0438-9557 Copyright © από την Ελληνική Γεωλογική Εταιρία Copyright © by the Geological Society of Greece 12o ΔΙΕΘΝΕΣ ΣΥΝΕΔΡΙΟ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΓΕΩΛΟΓΙΚΗΣ ΕΤΑΙΡΙΑΣ ΠΛΑΝΗΤΗΣ ΓΗ: Γεωλογικές Διεργασίες και Βιώσιμη Ανάπτυξη Υπό την Αιγίδα του Υπουργείου Περιβάλλοντος, Ενέργειας και Κλιματικής Αλλαγής 12th INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF GREECE PLANET EARTH: Geological Processes and Sustainable Development Under the Aegis of the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change ΠΡΑΚΤΙΚΑ / PROCEEDINGS ΕΠΙΜΕΛΕΙΑ ΕΚΔΟΣΗΣ EDITORS Γ. -

Internship Programme

Internship programme 0 Internship programme Index Tomar School of Technology ........................................................................................................ 2 Tomar School of Management ..................................................................................................... 3 Abrantes School of Technology .................................................................................................... 8 1 Internship programme Tomar School of Technology List of bodies with whom ESTT has established agreements Câmara Municipal de Abrantes [Municipality of Abrantes] ACIAAR – Associação do centro de Interpretação de Arqueologia do Alto Ribatejo [Archaeological Interpretation Centre of Alto Ribatejo] ALPESO Construções, S.A. Ambisig – Ambiente e Sistemas de Informação Geográfica, Lda. Arqueohoje Arqueolab, Lda. Caima – Indústria de Celulose, S.A. Câmara Municipal da Marinha Grande [Municipality of Marinha Grande] Câmara Municipal de Figueiró dos Vinhos [Municipality of Figueiró dos Vinhos] Câmara Municipal de Mação [Municipality of Mação] Câmara Municipal de Ourém [Municipality of Ourém] Câmara Municipal de Sintra [Municipality of Sintra] Câmara Municipal de Tavira [Municipality of Tavira] Câmara Municipal de Tomar [Municipality of Tomar] Câmara Municipal do Porto [Municipality of Porto] Centro Português de Geo-História [Portuguese Geohistory Centre] CNOTINFOR – Centro de Novas Tecnologias da Informação, Lda. Construções Aquino & Rodrigues, S.A. Construções Pastilha & Pastilha, S.A. Convento de Cristo -

Greek Nursery School Teachers' Thoughts and Self-Efficacy on Using

Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning Volume 12, 2016 Cite as: Goumas, S., Symeonidis, S., & Salonidis, S. (2016). Greek nursery school teachers’ thoughts and self-efficacy on using ICT in relation to their school unit position: The case of Kavala. Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Life Long Learning, 12, 33-55. Retrieved from http://www.ijello.org/Volume12/IJELLv12p033-055Goumas2208.pdf Greek Nursery School Teachers’ Thoughts and Self-Efficacy on using ICT in Relation to Their School Unit Position: The Case of Kavala Stefanos Goumas, Symeon Symeonidis, and Michail Salonidis Business Administration Department, Technological Educational Institute of Eastern Macedonian and Trace, Kavala, Greece [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this research is the exploration of the opinions and level of self-efficacy in the usage of Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) of teachers in Greek pre-schools in the learning process and administration of nurseries. By using the term “usage and utilisation of ICTs in the learning process” we mean the utilisation of the capabilities that new technologies offer in an educationally appropriate way so that the learning process yields positive results. By using the term “self-efficacy” we describe the strength of one’s belief in one’s own ability to use the capabilities he or she possess. In this way, the beliefs of the person in his or her ability to use a personal computer constitute the self-efficacy in computer usage. The research sample consists of 128 pre-school teachers that work in the prefecture of Kavala. Kavala’s prefecture is a repre- sentative example of an Education Authority since it consists of urban, suburban, and rural areas.