Southeast Houston: from Pastures to South Park to MLK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Espersonespersonesperson 808 Travis Street & 815 Walker Avenue • Houston, Texas

THETHETHE ESPERSONESPERSONESPERSON 808 TRAVIS STREET & 815 WALKER AVENUE • HOUSTON, TEXAS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY THETHETHE ESPERSONESPERSONESPERSON 808 TRAVIS STREET & 815 WALKER AVENUE • HOUSTON, TEXAS HFF, as the exclusive representative of the owner, is pleased to offer for sale a 100% fee simple interest in Esperson (the “Property”), a 19 and 27-story, 599,107 square foot office building located in Houston’s central business district. Constructed in 1927 and 1941 respectively, Esperson is the only iconic structure of Italian Renaissance in Houston’s most densified employment center. The property is currently 62% leased with 4 years remaining average lease term and is situated on 1.447 acres, a full city block. Located at the intersection of Rusk and Walker Street, Esperson has direct access to Houston’s METRO Rail and 7.5 mile underground tunnel system. Over the last 36 months, ownership invested nearly $9 million in non-leasing capital, positioning the asset at the top of its competitive set. Today, considerable value creation is achievable through rolling current in-place rents to market and through the lease up of the remaining 226,561 square feet of vacant space. Redeveloping and expanding Houston’s CBD infrastructure – realized through rebuilt streets – highways, new mass transit and enhanced public utilities coupled with new office, multi-family, and retail projects have transformed Houston’s core into a vibrant, modern 24/7 environment for people to live, work and play. Esperson offers investors prestige, history, quality, abundant amenities, and a prime location in Houston’s largest employment center. INVESTMENT SALES H. DAN MILLER, CCIM, SIOR Senior Managing Director Tel: (713) 852-3576 [email protected] MARTIN T. -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. LJ 2531

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2001 Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001) Kevin Hopkins John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Law and Race Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Hopkins, Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/153 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery KEvIN HOPKINS* "We must make sure that their deaths have posthumous meaning. We must make sure that from now until the end of days all humankind stares this evil in the face.., and only then can we be sure it will never arise again." President Ronald Reagan' INTRODUCTION: Tm BIG PAYBACK In recent months, claims for reparations for slavery have gained new popular- ity amongst black intellectuals and trial lawyers and have been given additional momentum by the publication of Randall Robinson's controversial and thought- provoking book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks.2 In The Debt, Robinson makes a serious and persuasive case for the payment of reparations by the United States government to African-Americans for both the injustices done to their ancestors during slavery and the effect of those wrongs on the current * Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School. -

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers Papers, 1950-2001

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Biggers, John Thomas, 1924-2001. Title: John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1179 Extent: 31 linear feet (62 boxes), 6 oversized papers boxes and 2 oversized papers folders (OP), 2 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 1 extra-oversized paper (XOP), and AV Masters: .25 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers of African American mural artist and professor John Biggers including correspondence, photographs, printed materials, professional materials, subject files, writings, and audiovisual materials documenting his work as an artist and educator. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

NGA Retailer Membership List October 2013

NGA Retailer Membership List October 2013 Company Name City State 159-MP Corp. dba Foodtown Brooklyn NY 2945 Meat & Produce, Inc. dba Foodtown Bronx NY 5th Street IGA Minden NE 8772 Meat Corporation dba Key Food #1160 Brooklyn NY A & R Supermarkets, Inc. dba Sav-Mor Calera AL A.J.C.Food Market Corp. dba Foodtown Bronx NY ADAMCO, Inc. Coeur D Alene ID Adams & Lindsey Lakeway IGA dba Lakeway IGA Paris TN Adrian's Market Inc. dba Adrian's Market Hopwood PA Akins Foods, Inc. Spokane Vly WA Akins Harvest Foods- Quincy Quincy WA Akins Harvest Foods-Bonners Ferry Bonner's Ferry ID Alaska Growth Business Corp. dba Howser's IGA Supermarket Haines AK Albert E. Lees, Inc. dba Lees Supermarket Westport Pt MA Alex Lee, Inc. dba Lowe's Food Stores Inc. Hickory NC Allegiance Retail Services, LLC Iselin NJ Alpena Supermarket, Inc. dba Neimans Family Market Alpena MI American Consumers, Inc. dba Shop-Rite Supermarkets Rossville GA Americana Grocery of MD Silver Spring MD Anderson's Market Glen Arbor MI Angeli Foods Company dba Angeli's Iron River MI Angelo & Joe Market Inc. Little Neck NY Antonico Food Corp. dba La Bella Marketplace Staten Island NY Asker's Thrift Inc., dba Asker's Harvest Foods Grangeville ID Autry Greer & Sons, Inc. Mobile AL B & K Enterprises Inc. dba Alexandria County Market Alexandria KY B & R Stores, Inc. dba Russ' Market; Super Saver, Best Apple Market Lincoln NE B & S Inc. - Windham IGA Willimantic CT B. Green & Company, Inc. Baltimore MD B.W. Bishop & Sons, Inc. dba Bishops Orchards Guilford CT Baesler's, Inc. -

Harrisburg Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone May 2016 Inside Cover Table of Contents

Existing Conditions Harrisburg Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone May 2016 Inside Cover Table of Contents Introduction Housing LOCATION .......................................................... 5 HOUSING STOCK ................................................ 29 EXISTING PL ANS AND STUDIES ............................... 12 HOUSING TYpeS ................................................. 30 Land Use & Mobility AGE ................................................................ 30 EleMENTS OF THE DISTRICT ................................... 13 Crime LAND USE/PROpeRTY CL ASSIFICATION ..................... 13 Economic Indicators ROADWAYS ........................................................ 16 BUSINESS SUMMARY ............................................ 35 TRAFFIC VOLUMES ............................................... 16 RETAIL TRADE .................................................... 38 RAILROAD ......................................................... 17 DAY TIME POPUL ATION .......................................... 40 BIKEWAYS ......................................................... 17 Planned Infrastructure Improvements RAILS TO TRAILS ................................................. 17 CAPITAL IMPROveMENTS ....................................... 45 PARKS & TRAILS ................................................. 21 RebUILD HOUSTON +5 ........................................ 45 REIMAGINE METRO ............................................. 21 Observations People OBSERVATIONS ................................................... 49 -

THE CONNERS of WACO: BLACK PROFESSIONALS in TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXAS by VIRGINIA LEE SPURLIN, B.A., M.A

THE CONNERS OF WACO: BLACK PROFESSIONALS IN TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXAS by VIRGINIA LEE SPURLIN, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved ~r·rp~(n oj the Committee li =:::::.., } ,}\ )\ •\ rJ <. I ) Accepted May, 1991 lAd ioi r2 1^^/ hJo 3? Cs-^.S- Copyright Virginia Lee Spurlin, 1991 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is a dream turned into a reality because of the goodness and generosity of the people who aided me in its completion. I am especially grateful to the sister of Jeffie Conner, Vera Malone, and her daughter, Vivienne Mayes, for donating the Conner papers to Baylor University. Kent Keeth, Ellen Brown, William Ming, and Virginia Ming helped me immensely at the Texas Collection at Baylor. I appreciated the assistance given me by Jene Wright at the Waco Public Library. Rowena Keatts, the librarian at Paul Quinn College, deserves my plaudits for having the foresight to preserve copies of the Waco Messenger, a valuable took for historical research about blacks in Waco and McLennan County. The staff members of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Texas State Library in Austin along with those at the Prairie View A and M University Library gave me aid, information, and guidance for which I thank them. Kathy Haigood and Fran Thompson expended time in locating records of the McLennan County School District for me. I certainly appreciated their efforts. Much appreciation also goes to Robert H. demons, the county school superintendent. -

Houston-Galveston, Texas Managing Coastal Subsidence

HOUSTON-GALVESTON, TEXAS Managing coastal subsidence TEXAS he greater Houston area, possibly more than any other Lake Livingston A N D S metropolitan area in the United States, has been adversely U P L L affected by land subsidence. Extensive subsidence, caused T A S T A mainly by ground-water pumping but also by oil and gas extraction, O C T r has increased the frequency of flooding, caused extensive damage to Subsidence study area i n i t y industrial and transportation infrastructure, motivated major in- R i v vestments in levees, reservoirs, and surface-water distribution facili- e S r D N ties, and caused substantial loss of wetland habitat. Lake Houston A L W O Although regional land subsidence is often subtle and difficult to L detect, there are localities in and near Houston where the effects are Houston quite evident. In this low-lying coastal environment, as much as 10 L Galveston feet of subsidence has shifted the position of the coastline and A Bay T changed the distribution of wetlands and aquatic vegetation. In fact, S A Texas City the San Jacinto Battleground State Historical Park, site of the battle O Galveston that won Texas independence, is now partly submerged. This park, C Gulf of Mexico about 20 miles east of downtown Houston on the shores of Galveston Bay, commemorates the April 21, 1836, victory of Texans 0 20 Miles led by Sam Houston over Mexican forces led by Santa Ana. About 0 20 Kilometers 100 acres of the park are now under water due to subsidence, and A road (below right) that provided access to the San Jacinto Monument was closed due to flood- ing caused by subsidence. -

DOWNTOWN HOUSTON, TEXAS LOCATION Situated on the Edge of the Skyline and Shopping Districts Downtown, 1111 Travis Is the Perfect Downtown Retail Location

DOWNTOWN HOUSTON, TEXAS LOCATION Situated on the edge of the Skyline and Shopping districts Downtown, 1111 Travis is the perfect downtown retail location. In addition to ground level access. The lower level is open to the Downtown tunnels. THE WOODLANDS DRIVE TIMES KINGWOOD MINUTES TO: Houston Heights: 10 minutes River Oaks: 11 minutes West University: 14 minutes Memorial: 16 minutes 290 249 Galleria: 16 minutes IAH 45 Tanglewood: 14 minutes CYPRESS Med Center:12 minutes Katy: 31 minutes 59 Cypress: 29 minutes 6 8 Hobby Airport: 18 minutes 290 90 George Bush Airport: 22 minutes Sugar Land: 25 minutes 610 Port of Houston: 32 minutes HOUSTON 10 HEIGHTS 10 Space Center Houston: 24 minutes MEMORIAL KATY 10 330 99 TANGLEWOOD PORT OF Woodlands: 31 minutes HOUSTON 8 DOWNTOWN THE GALLERIA RIVER OAKS HOUSTON Kingwood: 33 minutes WEST U 225 TEXAS MEDICAL 610 CENTER 99 90 HOBBY 146 35 90 3 59 SPACE CENTER 45 HOUSTON SUGARLAND 6 288 BAYBROOK THE BUILDING OFFICE SPACE: 457,900 SQ FT RETAIL: 17,700 SQ FT TOTAL: 838,800 SQ FT TRAVIS SITE MAP GROUND LEVEL DALLAS LAMAR BIKE PATH RETAIL SPACE RETAIL SPACE METRO RAIL MAIN STREET SQUARE STOP SITE MAP LOWER LEVEL LOWER LEVEL RETAIL SPACE LOWER LEVEL PARKING TUNNEL ACCESS LOWER LEVEL PARKING RETAIL SPACE GROUND LEVEL Main Street Frontage 3,037 SQ FT 7,771 SQ FT RETAIL SPACE GROUND LEVEL Main Street frontage Metro stop outside door Exposure to the Metro line RETAIL SPACE GROUND LEVEL Houston’s Metro Rail, Main Street Square stop is located directly outside the ground level retail space. -

07-77817-02 Final Report Dickinson Bayou

Dickinson Bayou Watershed Protection Plan February 2009 Dickinson Bayou Watershed Partnership 1 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY The preparation of this report was financed though grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 10 SUMMARY OF MILESTONES ........................................................................................................................ 13 FORWARD ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 The Dickinson Bayou Watershed .................................................................................................................. -

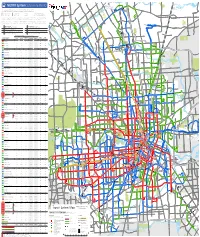

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g.