Joni Mitchell's Gender Identity, 1975-76 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Songs About Joni

Songs About Joni Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: Dec. 28, 2020 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1967 Lady Of Rohan Chuck Mitchell Unreleased 1969 Song To A Cactus Tree Graham Nash Unreleased Why, Baby Why Graham Nash Unreleased Guinnevere Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Pre-Road Downs Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Portrait Of The Lady As A Young Artist Seatrain Seatrain (Debut LP) 1970 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Neil Young After The Goldrush Our House Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Déjà Vu 1971 Just Joni Mitchell Charles John Quarto Unreleased Better Days Graham Nash Songs For Beginners I Used To Be A King Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Simple Man Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Love Has Brought Me Around James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon You Can Close Your Eyes James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon 1972 New Tune James Taylor One Man Dog 1973 It's Been A Long Time Eric Andersen Stages: The Lost Album You'’ll Never Be The Same Graham Nash Wild Tales Song For Joni Dave Van Ronk songs for ageing children Sweet Joni Neil Young Unreleased Concert Recording 1975 She Lays It On The Line Ronee Blakley Welcome Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Wind On The Water 1976 I Used To Be A King David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Simple Man David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Song For Joni Denise Kaufmann Dream Flight Mellow -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

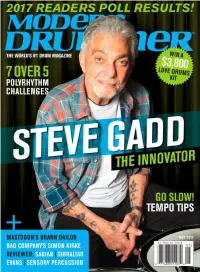

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection

Search artists, albums and more... ' Explore + Marketplace + Community + * ) + Dashboard Collection Wantlist Lists Submissions Drafts Export Settings Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection Collection Value:* Min $3,698.90 Med $9,882.74 Max $29,014.80 Sort Artist A-Z Folder Keepers (500) Show 250 $ % & " Remove Selected Keepers (500) ! Move Selected Artist #, Title, Label, Year, Format Min Median Max Added Rating Notes Johnny Cash - American Recordings $43.37 $61.24 $105.63 over 5 years ago ((((( #366 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release American Recordings, American Recordings 9-45520-1, 1-45520 Near Mint (NM or M-) Shrink 1994 US Johnny Cash - At Folsom Prison $4.50 $29.97 $175.84 over 5 years ago ((((( #88 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Very Good Plus (VG+) US 1st Release Columbia CS 9639 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1968 US Johnny Cash - With His Hot And Blue Guitar $34.99 $139.97 $221.60 about 1 year ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Mic Very Good Plus (VG+) top & spine clear taped Sun (9), Sun (9), Sun (9) 1220, LP-1220, LP 1220 Very Good (VG) 1957 US Joni Mitchell - Blue $4.00 $36.50 $129.95 over 6 years ago ((((( #30 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album, Pit Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release Reprise Records MS 2038 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1971 US Joni Mitchell - Clouds $4.03 $15.49 $106.30 over 2 years ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Ter Near Mint (NM or M-) Reprise Records RS 6341 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1969 US Joni Mitchell - Court And Spark $1.99 $5.98 $19.99 -

Magnum Moon-- Naturally--In the Arkansas Derby

SUNDAY, APRIL 15, 2018 MAGNUM MOON-- FAMED SPORTSWRITER BILL NACK DEAD AT 77 By Bill Finley NATURALLY--IN THE Bill Nack, widely recognized as one of the most talented racing writers of all time, passed away Friday at his home in ARKANSAS DERBY Washington D.C. Nack died following a bout with cancer. He was 77. Best known for his work with Sports Illustrated, where he was employed from 1978 to 2001, Nack covered many sports, but racing was his primary assignment and his first love. His 1990 story Pure Heart on the passing of Secretariat was chosen as one of SI=s 60 most iconic stories. His 1975 book on Secretariat, ASecretariat : The Making of a Champion@ is considered the definitive book on the 1973 Triple Crown winner. ABill was a great reporter, a great writer a great friend, a great colleague,@ said Steve Crist, the former racing writer for the New York Times who later became the publisher of the Daily Racing Form. AHis work on Secretariat was the best turf writing ever done.@ Cont. p11 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Magnum Moon | Coady photography WINX TIES BLACK CAVIAR’S WIN RECORD Trainer Todd Pletcher entered Saturday=s GI Arkansas Derby Winx (Aus) (Street Cry {Ire}) saluted in her 25th consecutive race, having saddled back-to-back winners of the race in the form of tying Black Caviar (Aus) (Bel Esprit {Aus})’s win record, when Overanalyze (Dixie Union) and Danza (Street Boss) in 2013 and scoring in her second G1 Queen Elizabeth S. at Royal Randwick on 2014, respectively. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Report on the 1975 Survey of Users of the Services of Radio Stations Wwv and Wwvh

'JM ^^ t*.;: .,-.;, .'-ti ^^#' • J* .^: '•^i'-^v'-' '- \ • REFERENCE N B S V U) NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 674 ^''fff AU O* * U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/National Bureau of Standards Report On The 1975 Survey of Users of the Services of Radio Stations WWY and WWYH /OO ' .6/5753 . no,(o7i . /975, NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, the Office of Radiation Measurement and the following Center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center for Radiation Research: Nuclear Sciences; Applied Radiation — Laboratory Astrophysics ° — Cryogenics" — Electromagnetics" — Time and Frequency". -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Joni Mitchell," 1966-74

"All Pink and Clean and Full of Wonder?" Gendering "Joni Mitchell," 1966-74 Stuart Henderson Just before our love got lost you said: "I am as constant as a northern star." And I said: "Constantly in the darkness - Where 5 that at? Ifyou want me I'll be in the bar. " - "A Case of You," 1971 Joni Mitchell has always been difficult to categorize. A folksinger, a poet, a wife, a Canadian, a mother, a party girl, a rock star, a hermit, a jazz singer, a hippie, a painter: any or all of these descriptions could apply at any given time. Moreover, her musicianship, at once reminiscent of jazz, folk, blues, rock 'n' roll, even torch songs, has never lent itself to easy categorization. Through each successive stage of her career, her songwriting has grown ever more sincere and ever less predictable; she has, at every turn, re-figured her public persona, belied expectations, confounded those fans and critics who thought they knew who she was. And it has always been precisely here, between observers' expec- tations and her performance, that we find contested terrain. At stake in the late 1960s and early 1970s was the central concern for both the artist and her audience that "Joni Mitchell" was a stable identity which could be categorized, recognized, and understood. What came across as insta- bility to her fans and observers was born of Mitchell's view that the honest reflection of growth and transformation is the basic necessity of artistic expres- sion. As she explained in 1979: You have two options. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Ashton Patriotic Sublime.5.Pdf (9.823Mb)

commercial spaces like theaters, and to performances spanning the gamut from the solemn, to the joyous. This diversity encompassed celebrations outside the expected calendar of national days. Patriotic sentiment was even a key feature of events celebrating the economic and commercial expansion of the new nation. The commemorative celebration for the laying of the foundation-stone of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the “great national work which is intended and calculated to cement more strongly the union of the Eastern and the Western States,” took place on July 4, 1828.1 It beautifully illustrated the musical ties that bound different spaces together – in this case a parade route, a temporary outdoor civic space, and the permanent space of the Holliday Street Theatre. Organizers chose July Fourth for the event, wishing to signal civic pride and affective patriotism. Baltimore filled with visitors in the days before the celebration, so that on the morning of the Fourth the “immense throng of spectators…filled every window in Baltimore-street, and the pavement below….fifty thousand spectators, at least, must have been present.” The parade was massive and incorporated a great diversity of groups, including “bands of music, trades, and other bodies.” One focal point was a huge model, “completely rigged,” of a naval vessel, the “Union,” complete with uniformed sailors. Bands playing patriotic tunes were interspersed amongst the nationalist imagery on display: militia uniforms, banners emblazoned with patriotic verse, national flags, eagle figures, shields, and more. Charles Carrollton, one of the last surviving signers of the Declaration of Independence, gave the main public address at the site, accompanied by a march composed for the occasion, the “Carrollton March” (see Figure 2.4).