Secular Mode, Sacred Message: How Contemporary Christian Musicians Are Called by God to Perform Matthew .W Lauritsen St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017 JUNO FAN CHOICE (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Belly Roc Nation*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Hedley Universal Justin Bieber Def Jam*Universal Ruth B Columbia*Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Wild Things Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal One Dance ft. Wizkid & Kyla Drake Cash Money*Universal Treat You Better Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Spirits The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal Starboy ft. Daft Punk The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY IDLA ASSOCIATED LABEL DISTRIBUTION) Dangerous Woman Ariana Grande Republic*Universal A Head Full of Dreams Coldplay Parlophone*Warner Made in the A.M. One Direction Sony ANTI Rihanna Westbury Road*Universal This is Acting Sia RCA*Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Encore un Soir Céline Dion Sony Views Drake Cash Money*Universal You Want It Darker Leonard Cohen Sony Illuminate Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Starboy The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal ARTIST OF THE YEAR Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Leonard Cohen Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR Arkells Arkells*Universal Billy Talent Warner Tegan and Sara Warner Bros. -

Southern Gospel and CCM

Southern Gospel Music Copyright 1998 by David W. Cloud Tis edition May 6, 2014 ISBN 978-1-58318-148-5 Tis book is sold in print format but it is available for free distribution in eBook format--in pdf, mobi (for Kindle, etc.), and ePub. See the Free Book tab - www.wayofife.org. We do not allow distribution of this book from other web sites. Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayofife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry ii Table of Contents Introduction ..........................................................................1 History of Southern Gospel ................................................3 Worldliness .........................................................................10 Southern Gospel in Recent Years .....................................19 Southern Gospel and CCM ..............................................24 When to Avoid Southern Gospel Music .........................25 About Way of Life’s eBooks ..............................................30 Powerful Publications for Tese Times ...........................31 iii iv Introduction Southern gospel is not a single style of music. It is a classifcation of a broad range of harmonizing, country- tinged Christian music that originated in the southeastern part of the United States. Some Southern gospel is lovely and spiritual and seeks not to entertain the fesh but to edify the spirit. (Tere are also quartets that are not Southern gospel in style; an example is the Old Fashioned Revival Hour Quartet that was featured on Charles Fuller’s radio program.) We praise the Lord for all Christian music, Southern or otherwise, which doesn’t sound like the world, which has scriptural lyrics, which seeks solely to glorify Jesus Christ and edify the saints, and which is produced by faithful Christians. -

Gospel Reaching out Volume 2, Number 11 Department of Library Special Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Gospel Reaching Out Kentucky Library - Serials 11-1974 Gospel Reaching Out Volume 2, Number 11 Department of Library Special Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/gospel_ro Part of the Christianity Commons, Cultural History Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Music Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Department of Library Special Collections, "Gospel Reaching Out Volume 2, Number 11" (1974). Gospel Reaching Out. Paper 27. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/gospel_ro/27 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gospel Reaching Out by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. //W BULK RATE U. S. POSTAGE PAID PERMIT NO. 41 Q HORSE CAVE. KY. 42749 GOSPEL ADDRESS CORRECTION REQUESTED Q oqD ReachiM Out "GOSPEL MUSIC NEWS FROM THE 'HART' OF KENTUCKY' 104 VOLUME 2-NUMBER 11 HORSE CAVE, KENTUCKY 42749 NOVEMBER 1974 Hart County GMA Plans Family Niglit A gospel singing with the emphasis on families is coming up on November 16 at the Hart County High School. The theme of "Family Night" is in keeping with the idea that gospel music is music for the entire family. Numerous door prizes will be given in recognition of such things as largest family in attendance, couple married the longest, and many more. Talent for the singing has not been confirmed at press time although a number of the top groups in Southern Kentucky are expected to be on the program. -

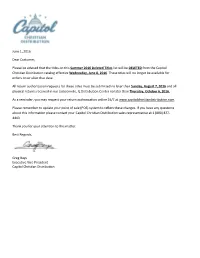

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please Be Advised That the Titles On

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please be advised that the titles on this Summer 2016 Deleted Titles list will be DELETED from the Capitol Christian Distribution catalog effective Wednesday, June 8, 2016. These titles will no longer be available for orders on or after that date. All return authorization requests for these titles must be submitted no later than Sunday, August 7, 2016 and all physical returns received in our Jacksonville, IL Distribution Center no later than Thursday, October 6, 2016. As a reminder, you may request your return authorization online 24/7 at www.capitolchristiandistribution.com. Please remember to update your point of sale (POS) system to reflect these changes. If you have any questions about this information please contact your Capitol Christian Distribution sales representative at 1 (800) 877- 4443. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Best Regards, Greg Bays Executive Vice President Capitol Christian Distribution CAPITOL CHRISTIAN DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2016 DELETED TITLES LIST Return Authorization Due Date August 7, 2016 • Physical Returns Due Date October 6, 2016 RECORDED MUSIC ARTIST TITLE UPC LABEL CONFIG Amy Grant Amy Grant 094639678525 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant My Father's Eyes 094639678624 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Never Alone 094639678723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Straight Ahead 094639679225 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Unguarded 094639679324 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant House Of Love 094639679829 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Behind The Eyes 094639680023 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant A Christmas To Remember 094639680122 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Simple Things 094639735723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Icon 5099973589624 Amy Grant Productions CD Seventh Day Slumber Finally Awake 094635270525 BEC Recordings CD Manafest Glory 094637094129 BEC Recordings CD KJ-52 The Yearbook 094637829523 BEC Recordings CD Hawk Nelson Hawk Nelson Is My Friend 094639418527 BEC Recordings CD The O.C. -

YLO89 Magazine

•YLO 91_Layout 1 2/13/13 3:02 PM Page 1 TRD COVER Youth Leaders Only / Music Resource Book / Volume 91 / Spring 2013 Cover: Red 25 Ways To Create A Crisis Page 6 When Volunteers Date Kids Page 8 The Crisis Head/Heart Disconnect Page 10 INSIDE: ConGRADulations! Class of 2013 Music-Media Grad Gift Page 18 Heart of the Artist: RED Page 15 Jeremy Camp Page 16 The American Bible Challenge: Jeff Foxworthy Interview Page 12 Worship Chord Charts from Gungor, Planetshakers, Elevation Worship, Everfound Page 42 y r t s i & n i c i M s u h t M u o g Y n i n z i i a m i i x d a e M M CRISIS: ® HANDLING THOSE “UH OH!” SITUATIONS •YLO 91_Layout 1 2/13/13 3:02 PM Page 2 >> TRD TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS MAIN/MILD/HOT ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY BY ARTIST 6 8 10 11 FEATURE 25 Ways To Create When Volunteers The Crisis I’m In A ARTICLES: Your Own Crisis Date Kids Disconnect Crisis NOW MAIN: 18 20 25 CONGRADULATIONS! PURPOSE FILM Artist: CLASS OF 2013 DVD GUNGOR Album Title: ConGRADulations! Class of 2013 Purpose A Creation Liturgy (Live) Song Title: Unstoppable Beautiful Things Study Theme: Sacrifice Life; Purpose Meaning Renewal MILD: 21 22 23 ELEVATION Artist: CAPITAL KINGS WORSHIP EVERFOUND Album Title: Capital Kings Nothing Is Wasted Everfound Song Title: You’ll Never Be Alone Nothing Is Wasted Never Beyond Repair Study Theme: God’s Presence Difficulty; Hope Within Grace HOT: 24 26 28 Artist: FLYLEAF JEKOB JSON Album Title: New Horizons Faith Hope Love Growing Pains Song Title: New Horizons Love Is All Brand New Study Theme: Hope; In God Love; Unconditional -

Capitalizing on My African American Christian Heritage in the Cultivation

Masthead Logo Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2019 Capitalizing on my African American Christian Heritage in the Cultivation of Spiritual Formation and Contemplative Spiritual Disciplines Claire Appiah [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Appiah, Claire, "Capitalizing on my African American Christian Heritage in the Cultivation of Spiritual Formation and Contemplative Spiritual Disciplines" (2019). Doctor of Ministry. 288. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/288 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY CAPITALIZING ON MY AFRICAN AMERICAN CHRISTIAN HERITAGE IN THE CULTIVATION OF SPIRITUAL FORMATION AND CONTEMPLATIVE SPIRITUAL DISCIPLINES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY CLAIRE APPIAH PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY, 2019 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Claire Appiah has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 21, 2019 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Clifford Berger, DMin Secondary Advisor: Carlos Jermaine Richard, DMin Lead Mentor: Jason Clark, PhD, DMin Expert Advisor: Clifford Berger, DMin Copyright © 2019 by Claire Appiah All rights reserved All quotations from the Bible are from the King James Version. -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

The Slow Integration of Instruments Into Christian Worship

Musical Offerings Volume 8 Number 1 Spring 2017 Article 2 3-28-2017 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Jonathan M. Lyons Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Christianity Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lyons, Jonathan M. (2017) "From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship," Musical Offerings: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2017.8.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol8/iss1/2 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Document Type Article Abstract The Christian church’s stance on the use of instruments in sacred music shifted through influences of church leaders, composers, and secular culture. Synthesizing the writings of early church leaders and church historians reveals a clear progression. The early musical practices of the church were connected to the Jewish synagogues. As recorded in the Old Testament, Jewish worship included instruments as assigned by one’s priestly tribe. -

Music for Contemporary Christians: What, Where, and When?

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 13/1 (Spring 2002): 184Ð209. Article copyright © 2002 by Ed Christian. Music for Contemporary Christians: What, Where, and When? Ed Christian Kutztown University of Pennsylvania What music is appropriate for Christians? What music is appropriate in worship? Is there a difference between music appropriate in church and music appropriate in a youth rally or concert? Is there a difference between lyrics ap- propriate for congregational singing and lyrics appropriate for a person to sing or listen to in private? Are some types of music inherently inappropriate for evangelism?1 These are important questions. Congregations have fought over them and even split over them.2 The answers given have often alienated young people from the church and even driven them to reject God. Some answers have rejuve- nated congregations; others have robbed congregations of vitality and shackled the work of the Holy Spirit. In some churches the great old hymns havenÕt been heard in years. Other churches came late to the Òpraise musicÓ wars, and music is still a controversial topic. Here, where praise music is found in the church service, it is probably accompanied by a single guitar or piano and sung without a trace of the enthusi- asm, joy, emotion, and repetition one hears when it is used in charismatic churches. Many churches prefer to use no praise choruses during the church service, some use nothing but praise choruses, and perhaps the majority use a mixture. What I call (with a grin) Òrock ÔnÕ roll church,Ó where such instruments 1 Those who have recently read my article ÒThe Christian & Rock Music: A Review-Essay,Ó may turn at once to the section headed ÒThe Scriptural Basis.Ó Those who havenÕt read it should read on. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Cedars, November 15, 1996 Cedarville College

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 11-15-1996 Cedars, November 15, 1996 Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville College, "Cedars, November 15, 1996" (1996). Cedars. 686. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/686 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How Much Do You Owe? Students At Olympics. • •••••••• PAGE 4 Grandparent's Day.... Mister Smith Goes Student Profile........... to Cedorville Business Etiquette. • •••••••• PAGE 6 Do You Know If You're A Senior? News shorts. • •••••••• PAGE 9 CEDARVILLE COLLEGE STUDENT PUBLICATION Basketball teams rise to opening night against W ilberforce Mark Mien Lady Jacket bench proved to be the Staff Writer difference. All 14 members of the So long fall, hello winter. Yep, it squad played, and 12 of them scor is that time of the year again. -

Multiple Choice

Unit 4: Renaissance Practice Test 1. The Renaissance may be described as an age of A. the “rebirth” of human creativity B. curiosity and individualism C. exploration and adventure D. all of the above 2. The dominant intellectual movement of the Renaissance was called A. paganism B. feudalism C. classicism D. humanism 3. The intellectual movement called humanism A. treated the Madonna as a childlike unearthly creature B. focused on human life and its accomplishments C. condemned any remnant of pagan antiquity D. focused on the afterlife in heaven and hell 4. The Renaissance in music occurred between A. 1000 and 1150 B. 1150 and 1450 C. 1450 and 1600 D. 1600 and 1750 5. Which of the following statements is not true of the Renaissance? A. Musical activity gradually shifted from the church to the court. B. The Catholic church was even more powerful in the Renaissance than during the Middle Ages. C. Every educated person was expected to be trained in music. D. Education was considered a status symbol by aristocrats and the upper middle class. 6. Many prominent Renaissance composers, who held important posts all over Europe, came from an area known at that time as A. England B. Spain C. Flanders D. Scandinavia 7. Which of the following statements is not true of Renaissance music? A. The Renaissance period is sometimes called “the golden age” of a cappella choral music because the music did not need instrumental accompaniment. B. The texture of Renaissance music is chiefly polyphonic. C. Instrumental music became more important than vocal music during the Renaissance.