Swami Vidyaranya's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1 Notes

Appendix 1 Notes The methodology of preparation of notes 1) The literal / etymological meaning is given. 2) It’s occurence in Vedic literature. 3) At some places view points of Vidyaranya’s predecessors are noted and Vidyaranya’s approach towards this concept as depicted in Anubhutiprakasa. The important concepts from Kevaladvaita Philosophy are considered here. Index 1) Adyaropa - Apavada 2) 3T5T - 3 1 ^ Anna - Annada 3) spTT^Abhava 4) Avasthatraya 5) 3T%rr Avidya 6) Ahartikara 7) 3TTriT^ Atman 8) Anand 9) Aesanatraya 10) Catuspada Brahma 11) Jiva 12) Tapatraya 13) f^lJ^Triguna 14)%^tTriputi A 15) n<|r«h<*J| Trivrtkarana 16) Dehtraya 17) Navaguna 1 8 ) ^ Nadi 19) Paiicakosa 20) Pancamahabhuta 21) Pancagnividya 320 22) Bhavavikara 23) ¥ lf% Bhranti 24) Bhedatraya 25) Madhuvidya 26) Wn Maya 2 7 ) 3 f % /% M u k t i / Moksa 28)T?TRasa 29) - W rfe Vyasti - Samasti 30) ^ Vani 3 1 ) f ^ V id y a 3 2 ) Vidyasadhanani 33) ?^^$danga 3 4 ) $odasakalapurusa 3 5 ) Sattatraya 3 6 ) Spatajihva 3 7 ) ^ Saptaiiga and Aekonovirhsatimukha 3 8 ) Samitpani 3 9 ) Sadhanacatu$taya 40) WJT^Sastanga 4 1 ) Saiinyasa 321 Adyaropa - Apvada means super imposition and means acknowledgement. means an act of attributing falsely or through mistake, erroneously attributing the properties of one thing to another considering by mistake a rope to be a snake or considering Brahman to be the material world, means right acknowledgement e.g. These terms do not occur in the Upanisads, though the essence of them was well taken. Adya ^ankaracarya has systematiZed them and in Kevaladvaita they are traditionaly handed down. -

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

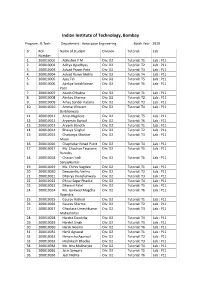

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

9. Brahman, Separate from the Jagat

Chapter 9: Brahman, Separate from the Jagat Question 1: Why does a human being see only towards the external vishayas? Answer: Katha Upanishad states in 2.1.1 that Paramatma has carved out the indriyas only outwards and therefore human beings see only towards external vishayas. परािच खान यतणृ वयभूतमापरा पयत नातरामन .् Question 2: What is the meaning of Visheshana? What are the two types of Visheshanas of Brahman? Answer: That guna of an object which separates it from other objects of same jati (=category) is known as Visheshana. For example, the ‘blue color’ is guna of blue lotus. This blue color separates this blue lotus from all other lotuses (lotus is a jati). Therefore, blue color is a Visheshana. The hanging hide of a cow separates it from all four-legged animals. Thus, this hanging hide is a Visheshana of cow among the jati of four-legged animals. The two types of Visheshanas of Brahman which are mentioned in Shruti are as follows:- ● Bhava-roopa Visheshana (Those Visheshanas which have existence) ● Abhava-roopa Visheshana (Those Visheshanas which do not exist) Question 3: Describe the bhava-roopa Visheshanas of Brahman? Answer: Visheshana refers to that guna of object which separates it from all other objects of same jati. Now jati of human beings is same as that of Brahman. Here, by Brahman, Ishvara is meant who is the nimitta karan of jagat. Both human being as well as Brahman (=Ishvara) has jnana and hence both are of same jati. However, there is great difference between both of them and thus Brahman (=Ishvara) is separated due to the following bhava-roopa Visheshanas:- ● Human beings have limited power, but Brahman is omnipotent. -

Vaishvanara Vidya.Pdf

VVAAIISSHHVVAANNAARRAA VVIIDDYYAA by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Publishers’ Note 3 I. The Panchagni Vidya 4 The Course Of The Soul After Death 5 II. Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 26 The Heaven As The Head Of The Universal Self 28 The Sun As The Eye Of The Universal Self 29 Air As The Breath Of The Universal Self 30 Space As The Body Of The Universal Self 30 Water As The Lower Belly Of The Universal Self 31 The Earth As The Feet Of The Universal Self 31 III. The Self As The Universal Whole 32 Prana 35 Vyana 35 Apana 36 Samana 36 Udana 36 The Need For Knowledge Is Stressed 37 IV. Conclusion 39 Vaishvanara Vidya Vidya by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Vaishvanara Vidya is the famous doctrine of the Cosmic Meditation described in the Fifth Chapter of the Chhandogya Upanishad. It is proceeded by an enunciation of another process of meditation known as the Panchagni Vidya. Though the two sections form independent themes and one can be studied and practised without reference to the other, it is in fact held by exponents of the Upanishads that the Vaishvanara Vidya is the panacea prescribed for the ills of life consequent upon the transmigratory process to which individuals are subject, a theme which is the central point that issues from a consideration of the Panchagni Vidya. This work consists of the lectures delivered by the author on this subject, and herein are reproduced these expositions dilating upon the two doctrines mentioned. -

4006 05.Patil Mahesh

Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) PEER REVIEW IMPACT FACTOR ISSN VOL- VI ISSUE-IX SEPTEMBER 2019 e-JOURNAL 5.707 2349-638x A Siddhantic Interpretation On ‘Bhutebhyo Hi Param Tasmaat Naasti Chinta Chikitsite’ Patil Mahesh Annasaheb Professor , Sant Gajanan Ayurveda Medical college , Mahagaon Abstract – Ayurvedic scholars are well aware that sarvadravyam panchbhoutikam asminarhte1ie..All the matters are derived from panchmahabhoot and similarly all the bodies are also made up of panchmahabhoot ( panchmahabhoot shari`r is amvaayiiti sharir ) In Ayurveda different definitions for the sharir had been told as Ekdhatwatmak , dwidhatwatmak , ashtadhatwatmak , chaturvimshatitatwatmaketc but the physiological definition is ‘dosh dhatu mala mulam hi shariram2ⁱ‘ and these Dosh , Dhatu ,Malas are the derivatives of panchmahabhoot(sloka ..) thus clearing that panchmahabhoot forms the foundation for formation of body.But whenever the issue of health and disease occurs the classics had defined it on the state of dosh dahtu level as Samdoshsamagnisamdhatu …and Rogastu doshvaishyamyam3. If we see keenly the origin of panchmahabhoot they have been derived from panchtanmatrasie subtle mahabhootas which in turn are are derivatives of preceding elements as Rajas and Tamas and so on till Avyakt. Whenever we speak about health and diseases relative to Dosh , Dhatu ,Malassamyavastha and vishamavastha indirectly it is concerned to the panchmahabhootas status only. Further if we probe into panchmahabhootas we can reach to rajas tamas -

Balabodha Sangraham

बालबोध सङ्ग्रहः - १ BALABODHA SANGRAHA - 1 A Non-detailed Text book for Vedic Students Compiled with blessings and under instructions and guidance of Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 69th Peethadhipathi and Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Sankara Vijayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 70th Peethadhipathi of Moolamnaya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Offered with devotion and humility by Sri Atma Bodha Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Kumbakonam Swamiji) Disciple of Pujyasri Kuvalayananda Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Tambudu Swamiji) Translation from Tamil by P.R.Kannan, Navi Mumbai Page 1 of 86 Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham ॥ श्रीमहागणपतये नमः ॥ ॥ श्री गु셁भ्यो नमः ॥ INTRODUCTION जगत्कामकलाकारं नािभस्थानं भुवः परम् । पदपस्य कामाक्षयाः महापीठमुपास्महे ॥ सदाििवसमारमभां िंकराचाययमध्यमाम् । ऄस्मदाचाययपययनतां वनदे गु셁परमपराम् ॥ We worship the Mahapitha of Devi Kamakshi‟s lotus feet, the originator of „Kamakala‟ in the world, the supreme navel-spot of the earth. We worship the Guru tradition, starting from Sadasiva, having Sankaracharya in the middle and coming down upto our present Acharya. This book is being published for use of students who join Veda Pathasala for the first year of Vedic studies and specially for those students who are between 7 and 12 years of age. This book is similar to the Non-detailed text books taught in school curriculum. We wish that Veda teachers should teach this book to their Veda students on Anadhyayana days (days on which Vedic teaching is prohibited) or according to their convenience and motivate the students. -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Subject : PHILOSOPHY

Subject : PHILOSOPHY 1. Classical Indian Philosophy Vedic and Upanisadic world-views : Rta & the cosmic order, the divine and the human realms; the centrality of the institution of yajna (sacrifice), the concept of ma & duty/obligation; theorist of creation Atman–Self (and not-self), jagrat, svapna, susupti and turiya, Brahman, sreyas and preyas Karma, samsara, moksa Carvaka : Pratyaksa as the only pramana, critique of anumana and sabda, rejection of non-material entities and of dharma and moksa Jainism : Concept of reality–sat, dravya, guna, prayaya, jiva, ajiva, anekantavada, syadvada and nayavada; theory of knowledge; bondage and liberation, Anuvrat & Mahavrat Bhddhism : Four noble truths, astangamarga, nirvana, madhyam pratipad, pratityasamutpada, ksanabhangavada, anatmavada Schools of Buddhism : Vaibhasika, Sautrantika, Yogacara and Madhyamika Nyaya : Prama and aprama, pramanya and apramanya, pramana : pratyaksa, niruikalpaka, savikalpaka, laukika and alaukika; anumana : anvayavyatireka, lingaparamarsa, vyapti; classification : vyaptigrahopayas, hetvabhasa, upamana; sabda : Sakti, laksana, akanksa, yogyata, sannidhi and tatparya, concept of God, arguments for the existence of God, adrsta, nihsryeasa Vaisesika : Concepts of padartha, dravya, guna, karma, samanya, samavaya, visesa, abhava, causation : Asatkaryavada, samavayi, asamavayi nimitta karana, paramanuvada, adrsta, nihsryeas Samkhya : Satkaryavada, prakrti and its evolutes, arguments for the existence of prakrti, nature of purusa, arguments for the existence and plurality of -

AGH-111 Course Title: Agricultural Heritage Credits: 1(1+0) Course Teacher Prof.Prasad

DEPARTMENT OF AGRONOMY Course No: AGH-111 Course Title: Agricultural Heritage Credits: 1(1+0) Course Teacher Prof.Prasad. M Patil Assistant Professor Department of Agronomy Contact: 7507445546, 9860208251 Email Id:[email protected] Prof.Prasad M.Patil (MSc.Agri, Agronomy) Department of Agronomy 7507445546, 9860208251 [email protected] Chapter-8 Plant production through indigenous traditional knowledge Astronomy -Prediction of Monsoon Rains; Parashara, Varamihira, Panchanga in Comparison to modern methods. Astronomy:-The Path of the sun being a fixed circle among the fixed stars is called ecliptic. 1. Modern scientific knowledge of methods of weather forecasting has originated recently. But ancient indigenous knowledge is unique to our country. 2. India had a glorious scientific and technological tradition in the past. 3. A scientific study of meteorology was made by our ancient astronomers and astrologers. 4. Even today, it is common that village astrologers (pandits) are right in surprisingly high percentage of their weather predications. 5. Meteorology is generally believed to be a new science. It may be new to the west, but not in India, where this science has existed since ancient times. 6. A systematic study of this science was made by our ancient astronomers and astrologers. 7. The rules are simple and costly apparatus are not required. Observations coupled with experience over centuries enhanced to develop meteorology. Prof.Prasad M.Patil (MSc.Agri, Agronomy) Department of Agronomy 7507445546, 9860208251 [email protected] Prediction of Monsoon Rains:- The ancient/indigenous method of weather forecast may be broadly classified into two Categories. 1. Observational Methods:- Atmospheric Changes Boi-indicators Chemical Changes Physical Changes Cloud forms and other sky features 2.