Goodnight-Loving Trail.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ranching Catalogue

Catalogue Ten –Part Four THE RANCHING CATALOGUE VOLUME TWO D-G Dorothy Sloan – Rare Books box 4825 ◆ austin, texas 78765-4825 Dorothy Sloan-Rare Books, Inc. Box 4825, Austin, Texas 78765-4825 Phone: (512) 477-8442 Fax: (512) 477-8602 Email: [email protected] www.sloanrarebooks.com All items are guaranteed to be in the described condition, authentic, and of clear title, and may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Purchases are shipped at custom- er’s expense. New customers are asked to provide payment with order, or to supply appropriate references. Institutions may receive deferred billing upon request. Residents of Texas will be charged appropriate state sales tax. Texas dealers must have a tax certificate on file. Catalogue edited by Dorothy Sloan and Jasmine Star Catalogue preparation assisted by Christine Gilbert, Manola de la Madrid (of the Autry Museum of Western Heritage), Peter L. Oliver, Aaron Russell, Anthony V. Sloan, Jason Star, Skye Thomsen & many others Typesetting by Aaron Russell Offset lithography by David Holman at Wind River Press Letterpress cover and book design by Bradley Hutchinson at Digital Letterpress Photography by Peter Oliver and Third Eye Photography INTRODUCTION here is a general belief that trail driving of cattle over long distances to market had its Tstart in Texas of post-Civil War days, when Tejanos were long on longhorns and short on cash, except for the worthless Confederate article. Like so many well-entrenched, traditional as- sumptions, this one is unwarranted. J. Evetts Haley, in editing one of the extremely rare accounts of the cattle drives to Califor- nia which preceded the Texas-to-Kansas experiment by a decade and a half, slapped the blame for this misunderstanding squarely on the writings of Emerson Hough. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

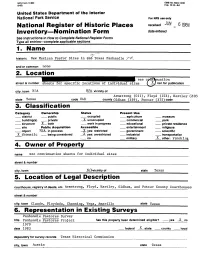

61934 Inventory Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 5. Location Of

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUN _ 61934 Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections _______________________________ 1. Name historic New Mexican Pastor Sites in this Texas Panhandle and/or common none 2. Location see c»nE*nuation street & number sheets for specific locations of individual sites ( XJ not for publication city, town vicinity of Armstrong (Oil), Floyd (153), Hartley (205 state Texas code 048 county Qldham (359), Potter (375) code______ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A jn process X yes: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other- ranrh-f-ng 4. Owner of Property name see continuation sheets for individual sites street & number city, town JI/Avicinity of state Texas 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Armstrong, Floyd, Hartley, Oldham, and Potter County Courthouses street & number city, town Claude, Floydada, Channing, Vega, Amarillo state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Panhandle Pastores Survey title Panhandle Pastores -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Land, Speculation, and Manipulation on the Pecos

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 2008 Land, Speculation, and Manipulation on the Pecos Stephen Bogener West Texas A&M University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Bogener, Stephen, "Land, Speculation, and Manipulation on the Pecos" (2008). Great Plains Quarterly. 1352. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1352 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. LAND, SPECULATION, AND MANIPULATION ONTHEPECOS STEPHEN BOGENER The Pecos River of the nineteenth century, manipulation of federal land laws followed the unlike its faint twenty-first century shadow, removal of Native Americans, the displace was a formidable watercourse. The river ment of Mexican American communities, stretches some 755 miles, from the Sangre de and the departure of major players in the Cristo Mountains northeast of Santa Fe to its cattle industry of the American West. One eventual merger with the Rio Grande. Control of the most ambitious engineering and irriga over the public domain of southeastern New tion ventures in nineteenth-century North Mexico came from controlling access to the America developed here from a simple idea Pecos, its tributaries and springs. In the arid in the mind of lawman Pat Garrett, better environment of New Mexico's Pecos Valley, known for slaying William Bonney, a.k.a. -

A Watershed Protection Plan for the Pecos River in Texas

AA WWaatteerrsshheedd PPrrootteeccttiioonn PPll aann ffoorr tthhee PPeeccooss RRiivveerr iinn TTeexxaass October 2008 A Watershed Protection Plan for the Pecos River in Texas Funded By: Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board (Project 04-11) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Investigating Agencies: Texas AgriLife Extension Service Texas AgriLife Research International Boundary and Water Commission, U.S. Section Texas Water Resources Institute Prepared by: Lucas Gregory, Texas Water Resources Institute and Will Hatler, Texas AgriLife Extension Service Funding for this project was provided through a Clean Water Act §319(h) Nonpoint Source Grant from the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Acknowledgments The Investigating Agencies would like to take this opportunity to thank the many individuals who have contributed to the success of this project. The development of this watershed protection plan would not have been possible without the cooperation and consolidation of efforts from everyone involved. First, we would like to thank the many landowners and other interested parties who have attended project meetings, participated in surveys, and provided invaluable input that has guided the development of this document. Your interest in this project and the Pecos River was and will continue to be instrumental in ensuring the future restoration and improvement of the health of this important natural resource. While there are too many of you to name here, we hope that your interest, involvement, and willingness to implement needed management measures will grow as progress is made and new phases of the watershed protection plan are initiated. Our gratitude is extended to the following individuals who have contributed their support, technical expertise, time, and/or advice during the project: Greg Huber, J.W. -

Cotton, Cattle, Railroads and Closing the Texas Frontier

Unit 8: Cotton, Cattle, Railroads and Closing the Texas Frontier 1866-1900 Civil War Games Peer Evaluation Sheet Your Name: ___________________________________________________________________ Game’s Name that you are evaluating: ______________________________________________ Game Creator’s:________________________________________________________________ For each question below, place the following number that corresponds with your answer Yes – 2 Somewhat – 1 No – 0 _____Were the objectives, directions, and rules of the game clear? Did you understand how to play? _____Does the game include good accessories (examples might include player pieces, a spinner, dice, etc…) _____Did the game ask relevant questions about the Civil War? Were the answers provided? _____Was the game fun to play? _____Was the game creative, artistic, and well designed? _____ TOTAL POINTS Unit 8 Vocabulary • Subsistence farming – the practice of growing enough crops to provide for one’s family group. • Commercial agriculture – the practice of growing surplus crops to sell for profit. • Vaqueros – Spanish term for cowboy. • Urbanization – the process of increasing human settlement in cities. • Settlement patterns – the spatial distribution of where humans inhabit the Earth. • Barbed Wire – strong wire with sharp points on it used as fencing. • Windmill – a mill that converts the energy of wind into rotational energy using blades. • Textiles – Cloth or woven fabric. • Open Range – prairie land where cattle roamed freely, without fences. • Cattle Drive – moving cattle in a large herd to the nearest railroad to be shipped to the North. Unit 8 Overview • Cotton, Cattle and Railroads • Cotton • Cattle Trails • Cowboys • Railroads • Military Posts in West Texas • European Immigration • Population Growth • Closing of the Open Range • Conflict with American Indians • Buffalo Soldiers • Quanah Parker • Windmills (windpump or windwheel) • Barbwire Native Americans vs. -

Westward Expansion 1763-1838, NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR STATE: (Rev

THEME: Westward Expansion 1763-1838, NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Mexico COUN T Yr NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Lincoln INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) Ni^Sil^'':^":^ :;' ; •'' r -' ''•' '''^ •'•'*•• ' ....'... •• ; ---••• ._•-.,... C OMMON: Lincoln, New Mexico AND/OR HISTORIC: Lincoln Historic District fei:^_®eAT*0N STREET AND NUMBER: U.S. Highway 380 CITY OR TOWN: CONGREZSSIONAL DISTRICT: Lincoln Second STA TE CQDE COUNTY : CODE New Mexico 35 Line oln 27 |fi';;f^:ji>i,$Si^i€^t{pN •.: STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC |S] District Q Building 1 1 Public Public Acquisition: 81 Occupied Yes: f-, , , . , S3 Restricted D Site fj Structure D Private Q In Process p>s] Unoccupied ""^ d r— i D *• i D Unrestricted rj Object S3 Botn CH Bein 9 Considere 1 _1 Preservation work — in progress ^sn NO PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [ | Agricultural | I Government | | Park [ | Transportation 1 1 Comments ^ Commercial 1 1 Industrial fcfl Private Residence HI Other fSoecifv) d Educational d Military Q Religious I | Entertainment ^1 Museum [ | Scientific R:ii>':: :->if|iittr fcj-p- t? •f5'P^ :-P Ji? FYP i* '(? T V ' ••:'-:' .,: .,: ... '•'-•.. :• •-•'..-•- x- •" x * •' ' • . ' • ..•"'•' ,. " • •' • -•'•'•,. • •-:.'••'• •..•*:' ;.yX->: . -- .•-.:•*•: • • •- . .•.;-,".•:.: - ' •'.'.-'.:-•:-,• •'•:• OWNER'S NAME: Mexico NewSTATE State of New Mexico, various private owners STREET AND NUMBER: State Capitol, Old Santa Fe Trail CITY OR TOWN: STA TE: CODF Santa Fe Npw Mexico 35 ^wsi^jf*^ . '. ,. /'• - .• ....•:.,. ..':;.. •- ;•'•:• Eft*:-;: ili&nrM .:»:*V.™ :i VT: . jL.C.Wtb, 1/C.dvKir: MW* : x ..: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Lincoln COUNTY: Lincoln County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: Cl TY OR TOWN: STA TE CODE Carrizozo N ew Mexico 35 praB^Pf|ll^i^^Wk'ti»:'ixi'stiN^':SuRVEys=.- ••' . -

Kindred Spirits Charles Goodnight and His Biographer J. Evetts Haley

Kindred Spirits Charles Goodnight and His Biographer J. Evetts Haley Edited by J.P. “Pat” McDaniel On a small rise in the remote Panhandle landscape outside of Amarillo sits a two- story wooden home, not at all spectacular to behold. But this is not just any home. This is the prairie residence of Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight—and Texas history happened here. A friendship forged from respect, mutual interests, and a shared sense of the importance of preserving the historical record, led author J. Evetts Haley and the trailblazing Goodnight to sit down inside of this house and record the stories of events that quite literally changed Texas. In 1925 the occupant of this prairie home, Charles Goodnight, was visited by a young collegiate historian from West Texas State Normal College in Canyon. J. Evetts Haley had been dispatched by his employer, the Panhandle Plains Historical Society, to secure an interview with the “Colonel.” This visit marked the beginning of a relationship that would impact the lives of both men. The story of those two kindred spirits has been best told by author B. Byron Price. He presented the Haley- Goodnight story in a book published in 1886 by the Nita Stewart Haley Memorial Library entitled Crafting a Southwestern Masterpiece: J. Evetts Haley and Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman. Price began the story of the friendship this way: On a hot summer afternoon in June 1925, a second-hand Model T rumbled down a short country lane in the Texas Panhandle. Pulling to a dusty stop beside an unpretentious white frame ranch house, an aspiring young historian unfolded his lean frame from behind the wheel and ambled to the door, unannounced. -

A History of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, 1869-1881

A history of the Mescalero Apache Reservation, 1869-1881 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mehren, Lawrence L. (Lawrence Lindsay), 1944- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 14:32:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/554055 See, >4Z- 2 fr,r- Loiu*ty\t+~ >MeV.r«cr coiU.c> e ■ A HISTORY OF THE MESCALERO APACHE RESERVATION, 1869-1881 by Lawrence Lindsay Mehren A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 9 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from, this thesis are allowable wihout special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: Associate Professor of History COPYRIGHTED BY LAWRENCE LINDSAY MEHREN 1969 iii PREFACE This thesis was conceived of a short two years ago, when I became interested.in the historical problems surrounding the Indian and his attempt to adjust to an Anglo-Saxon culture. -

Ranch Women of the Old West

Hereford Women Ranch Women of the Old West by Sandra Ostgaard Women certainly made very return to one’s hometown to find and the Jesse Evans Gang, Tunstall important contributions to a bride — or if the individual had hired individuals, including Billy America’s Western frontier. There a wife, to make arrangement to the Kid, Chavez y Chavez, Dick are some interesting stories about take her out West. This was the Brewer, Charlie Bowdre and the introduction of women in the beginning of adventure for many Doc Scurlock. The two factions West — particularly as cattlewomen a frontier woman. clashed over Tunstall’s death, with and wives of ranchers. These numerous people being killed women were not typical cowgirls. Susan McSween by both sides and culminating The frontier woman worked Susan McSween in the Battle of Lincoln, where hard in difficult settings and (Dec. 30, 1845- Susan was present. Her husband contributed in a big way to Jan. 3, 1931) was killed at the end of the civilizing the West. For the most was a prominent battle, despite being unarmed part, women married to ranchers cattlewoman of and attempting to surrender. were brought to the frontier after the 19th century. Susan struggled in the the male established himself. Once called the aftermath of the Lincoln County Conditions were rough in the “Cattle Queen of New Mexico,” War to make ends meet in the decade after the Civil War, making the widow of Alexander McSween, New Mexico Territory. She sought it difficult for men to provide who was a leading factor in the and received help from Tunstall’s suitable living conditions for Lincoln County War and was shot family in England.