Kindred Spirits Charles Goodnight and His Biographer J. Evetts Haley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

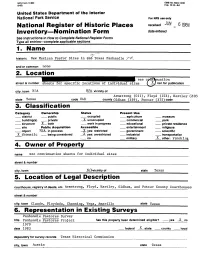

61934 Inventory Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 5. Location Of

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUN _ 61934 Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections _______________________________ 1. Name historic New Mexican Pastor Sites in this Texas Panhandle and/or common none 2. Location see c»nE*nuation street & number sheets for specific locations of individual sites ( XJ not for publication city, town vicinity of Armstrong (Oil), Floyd (153), Hartley (205 state Texas code 048 county Qldham (359), Potter (375) code______ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A jn process X yes: restricted government scientific X thematic being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other- ranrh-f-ng 4. Owner of Property name see continuation sheets for individual sites street & number city, town JI/Avicinity of state Texas 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Armstrong, Floyd, Hartley, Oldham, and Potter County Courthouses street & number city, town Claude, Floydada, Channing, Vega, Amarillo state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Panhandle Pastores Survey title Panhandle Pastores -

Cotton, Cattle, Railroads and Closing the Texas Frontier

Unit 8: Cotton, Cattle, Railroads and Closing the Texas Frontier 1866-1900 Civil War Games Peer Evaluation Sheet Your Name: ___________________________________________________________________ Game’s Name that you are evaluating: ______________________________________________ Game Creator’s:________________________________________________________________ For each question below, place the following number that corresponds with your answer Yes – 2 Somewhat – 1 No – 0 _____Were the objectives, directions, and rules of the game clear? Did you understand how to play? _____Does the game include good accessories (examples might include player pieces, a spinner, dice, etc…) _____Did the game ask relevant questions about the Civil War? Were the answers provided? _____Was the game fun to play? _____Was the game creative, artistic, and well designed? _____ TOTAL POINTS Unit 8 Vocabulary • Subsistence farming – the practice of growing enough crops to provide for one’s family group. • Commercial agriculture – the practice of growing surplus crops to sell for profit. • Vaqueros – Spanish term for cowboy. • Urbanization – the process of increasing human settlement in cities. • Settlement patterns – the spatial distribution of where humans inhabit the Earth. • Barbed Wire – strong wire with sharp points on it used as fencing. • Windmill – a mill that converts the energy of wind into rotational energy using blades. • Textiles – Cloth or woven fabric. • Open Range – prairie land where cattle roamed freely, without fences. • Cattle Drive – moving cattle in a large herd to the nearest railroad to be shipped to the North. Unit 8 Overview • Cotton, Cattle and Railroads • Cotton • Cattle Trails • Cowboys • Railroads • Military Posts in West Texas • European Immigration • Population Growth • Closing of the Open Range • Conflict with American Indians • Buffalo Soldiers • Quanah Parker • Windmills (windpump or windwheel) • Barbwire Native Americans vs. -

The Cattle Trails

The Cattle Trails Lesson Plan for 4th -7th Grades - Social Science and History OBJECTIVES The students will trace the development of the Texas cattle industry, beginning with the first trail drives of the 1850s, and the importance of cattle to Texas during and after the Civil War. TEKS Requirements: 1 - A identify major era in Texas History; 6 A & B - identify significant events from Reconstruction through the 20th century; 13B - impact of free enterprise and supply & demand on Texas economy. 6 A& B- development of the cattle industry ; political, economic, and social impact of the cattle industry 1 OVERVIEW & PURPOSE With the era of trail drives, beef was introduced to new markets across the country. A brief overview of how the Civil War affected ranchers and cattle; particularly how the longhorn roamed freely on the range and how this helped their population growth during the Civil War. After the war, The Great Trail Driving Era began, and the need for beef in the East caused the boom of the cattle industry. Building Background Ask the students if they can imagine taking a thousand cows up the highway, all the way from South Texas to Kansas. There are no cars and no actual roads - just dirt trails, the cows and horses. VERIFICATION AND INTRODUCTION How did Texans in the 1800’s do this? Why was it done? And who did it? In the days before barbed wire fences, cattle roamed freely on the open range. Ranchers used specific routes, known as cattle trails, to move their animals from grazing lands to market. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 tf*eM-. AO-"1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR lillllllililili NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC J A Ranch. AND/OR COMMON Goodnight Ranch. LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Pala Duro Rural Route _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Pala Duro Canyon „&_ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE A Q T^TT^IQ Armstrong Oil HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X—DISTRICT _ PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED — AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _|N PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -N° —MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Montie Ritchie STREET & NUMBER Palo Duro Rural Route CITY, TOWN STATE Clarendon VICINITY OF Texas 79226 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. County Clerk, Armstrong County STREET & NUMBER Box 309 CITY, TOWN STATE Claude. Texas 79019 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD —RUINS WALTER ED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Located in the Palo Duro Canyon of the Texas Panhandle, the J A Ranch Headquarters is a large and attractive complex consisting of 9 major constructions dating from various periods in the history of the ranch. -

Cowboy Meditation Primer

THE TRAVELING GUIDE to Mary McCray’s Cowboy Meditation Primer with history and definitions Trementina Books (2018) 1 Contents Introduction to this Guide 3 1. Starting Out: The Preface 7 2. Philadelphia to Cuervo: The Art of Preparing 12 3. Cuervo to Mosquero: The Art of Arriving 29 4. Mosquero to Capulin: The Art of Balancing 40 5. Capulin to Pueblo: The Art of Bowing 51 6. Pueblo to Trinidad: The Art of Suffering 60 7. Getting Back Home 64 Further Study 71 Origins of the Primer 74 2 Introduction to this Guide This PDF is both a reading companion and traveler’s guide to the book Cowboy Meditation Primer, poems about a late 1870s fictional character named Silas Cole, a heartbroken journalist who joins a cattle drive in order to learn how to be a real cowboy. He meets a cattle company traveling up the Goodnight-Loving Trail in New Mexico Territory; and not only do the cowboys give Silas a very real western adventure, they offer him a spiritual journey as well. Each chapter of this guide is divided into locations of the territory traversed in the book’s cattle drive which happens to loosely follow the famous Goodnight-Loving Trail. The guide offers history about the time period and definitions of words mentioned in the book. Each chapter has three sections: ● Historical definitions about cowboys and New Mexico Territory ● Zen/Buddhist concepts and definitions ● Trip information for those who want to make the trek themselves including what to see and where to stay along the way. The guide also contains maps, photos and questions to help guide you through the journey. -

Panhandle-Plains Historical Review 1928-2016

Panhandle-Plains Historical Review 1928-2016 2016/LXXXVII Zapata, Joel. “Palo Duro Canyon, Its People, and Their Landscapes: Building Culture(s) and a Sense of Place through the Environment since 1540.” 9-39. Grauer, Michael R. “Picturing Palo Duro: A Case Study 41.” 41-47. Jackson, Lisa. “Below the Rim: Racial Politics of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the Palo Duro Canyon.” 49-71. Seyffert, Kenneth D. “Environmental Change and Bird Populations in the Palo Duro Canyon State Park.” 73-85. Allison, Pamela S. and Joseph C. Cepeda. “Vegetation of Palo Duro Canyon: Legacy of Time and Place.” 87-105. 2015/ LXXXVI Turner, Leland. “Grasslands Beef Factories: Frontier Cattle Raisers in Northwest Texas and the Queensland Outback.” 7-28. Cammack, Bruce. “‘As If It Were a Pleasure’: The Life and Writings of John Watts Murray.” 31- 50. Turner, Alvin O. “The Greer County Decision: The Facts that Mattered.” 53-72. MacDonald, Bonney. “Receiving Genesis and the Georgics in Cather’s My Ántonia: Literature Fitted to the Land.” 75-85. Weaver, Bobby D. “Oilfield Follies: The Building of the Don D. Harrington Petroleum Wing.” 87- 99. 2014 / LXXXV Stuntz, Jean. “Early Settlement of the Panhandle by Women.” 9-18. Von Lintel, Amy M. “‘The Little Girl of the Texas Plains’: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Panhandle Years.” 21-56. Easley-McPherson, Hillarie. “The Politics of Reform: Women of the WCTU in Canadian, Texas, 1902-1920.” 59-80. Vanover, Mildred E. “‘My Museum’: The Susan Janney Allen Collection and Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.” 83-104. Hubbart, Maureen. Archival Review: “Letters of Elizabeth Smith.” 105-112. -

Charles Goodnight Area- Retiree Itinerary

Charles Goodnight Area- Retiree Itinerary The northeast part of the Texas Forts Trail Region is only an hour from Fort Worth and makes for the perfect weekend getaway. This part of the region includes two forts, many museums, beautiful scenic drives and the infamous Crazy Water. Jacksboro Fort Richardson in Jacksboro was established in 1867 and then abandoned in 1878, leaving most of the building in ruin. The Fort’s remaining seven structures have been restored and are now maintained by Texas Parks and Wildlife and are part of the National Historic Landmark that is Fort Richardson. While at the park, enjoy other activities such as hiking, biking, nature and historical studies and fishing. Drive right down the road and step back in time at the Jack County Museum. See one of the oldest homes in Jack County, which witnessed the birth of the Texas 4-H Club, and then the Corn Club, in 1907. There are also artifacts from life in early Jack County and military exhibits. Graham From the museum, head over and savor lunch from 526 Pizza Studio. Their wide variety of toppings is sure to hit the spot, and the food is anything but dull. Make sure to eat up because next up is Fort Belknap. Established in 1851, Fort Belknap was the northern mainstay of the Texas frontier defense. Walk the grounds and see the remaining buildings in the park-like setting. After you’ve walked off your lunch and stretched your legs, head back through Graham to Wildcatter Ranch Resort and Spa. The Wildcatter Ranch offers beautiful country scenery and a relaxing atmosphere. -

June 2008 Charles Goodnight, Father of the Texas Panhandle. by William

Book Review: Charles Goodnight, Father of the Texas Panhandle, William T. Hagan Item Type text; Book review Citation Thorpe, J. (2008). Book Review: Charles Goodnight, Father of the Texas Panhandle, William T. Hagan. Rangelands, 30(3), 67. DOI 10.2111/1551-501X(2008)30[67:BR]2.0.CO;2 Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Rangelands Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 29/09/2021 13:06:13 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/640558 BOOK REVIEW Charles Goodnight, Father of the Texas Panhandle. By William T. Hagan. 2007. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, USA. 147 p. US$26.95. hardcover. ISBN 978-0-8061-3827-5. At 140 pages, this concise volume (a perfect supplemental reading for Range 101?) tells the story of legendary Charles Goodnight and his pivotal role in the development of western ranching. Arising from humble, hardscrabble origins, Goodnight became, in various stages, an Indian fi ghter, a pioneering trail drover, an audacious open-range rancher, and fi nally, a facilitator of an advancing civilization that ushered in the end of his era. Goodnight fi rst partnered with the more experienced Oliver Loving to gather and drive 2,000 head of Longhorns to supply beef to the Navaho and Apache held in miserable captivity at Ft. Sumner, New Mexico. The 600-mile drive involved 18 drovers (no drinking, gambling, or fi ghting allowed), a chuck wagon (a Goodnight invention) drawn by twenty oxen, and a desperate 100-mile stretch with little grass and no water. -

A Guide to the Texas Plains Trail

A Guide to the Texas Plains Trail 50th ANNIVERSARY CARAVAN July 29-31, 2019 We’re thrilled you’re able to come along with us Fifty years later, a few on the Texas Plains Trail 50th Anniversary Caravan things have changed. Even to kick off our second half century of heritage tour- the map — which in 1968 ism in the Lone Star State! didn’t have, for instance, Here’s how the original 1968 “Ride the Texas the full Loop 289 in Lub- Plains Trail” map and brochure produced by the bock (1972); the complet- Texas Highway Department described the part of ed Interstate 27 (1992); the state we’ll be seeing: Caprock Canyons State Park (1984); the restored The Texas Plains Trail spans a vast area of Charles Goodnight House the High Plains region of Texas. The tableland (2012); or the Route 66 is called the Llano Estacado, an ancient Spanish National Historic District term generally interpreted to mean “ staked in Amarillo (1994). plains.” Much of the Trail slices through what These changes have residents call the “Golden Spread,” a reference led us to make a few to this immensely rich agricultural, mineral minor departures from the exact 1968 Texas Travel and industrial region. Geographically this is the Trail map. southernmost extension of the Great Plains of The city population figures from 1968 have the United States. changed a lot, with major cities gaining population Once the entire plains were grasslands. and many smaller ones losing some. Our demo- Not a fence, not a single tree or shrub grew on graphic makeup has shifted, and so have our per- the tablelands-—only grass, as trackless as the ceptions of the indigenous and immigrant peoples sea. -

The Story of the Cattle Trade…

The Story of the Cattle Trade… Lesson Objectives To understand the origins of the Cattle Industry and the new developments that occurred in the 1860s To recognise the factors that caused these changes and how they link with other aspects of the course To understand the role of the cowboy. The Story of the Cattle Trade… Beginnings.. Beginnings in Texas Cattle, just like horses, were first brought to America by the European settlers. By the 1850s, southern Texas was the major centre for cattle farming. The Texas longhorns were a breed that had developed from the original Spanish imports. They were very hardy and could survive on the open range in Texas. Their one drawback was the Texas – the relatively poor quality and quantity of their meat. original centre of the In the 1850s beef became a popular food, and the Texan Cattle cattle ranchers became prosperous. Then came the Industry American Civil War. Texas fought on the losing The cattle are The price of left untended beef falls as The Texan Confederate side. At the end of the war the Texans during Civil supply is cattle owners returned to their ranches to find their cattle herds had War. They outstripping need to find breed and demand . new markets grown dramatically. It is estimated that in 1865 there number for their increase cows.. were roughly five million cattle in Texas. Therefore, dramatically.. supply was totally outstripping demand in Texas and beef prices fell dramatically. The Story of the Cattle Trade… The need for cattle drives. Cattle were not worth much unless they could be sold. -

Palo Duro Canyon

Chapter 15 PALO DURO CANYON Palo Duro Canyon is a canyon system of the Caprock Escarpment located in the Texas Panhandle approximately 15 miles southeast of the city of Amarillo. There are also branch canyons that feed into the main Palo Duro Canyon that are much closer to Amarillo. The Panhandle city of Canyon is 12 miles west of the beginning of the Palo Duro Canyon. Escarpment is a geographical term used to describe a long, steep slope, especially one at the edge of a plateau or separating areas of land at different heights. Unbeknown to most people, Palo Duro is the second-largest canyon in the United States. It is approximately 120 miles long and stretches directionally from west to southeast. The average width is 6 miles, but with the crevices it reaches a width of 50 miles at several places. Its depth averages approximately 820 feet, but in some locations, it increases to 1,000. The elevation ranges from 3,500 feet above sea level on the prairie rim of the canyon to 2,380 feet on the floor below. 1 Palo Duro is derived from the Spanish meaning “hard wood” or, more exactly, “hard stick.” It has been named the Grand Canyon of Texas, both for its size and for the dramatic geological features, including the multicolored layers of rock and steep mesa walls similar to those of the Grand Canyon. From the floor looking upward, the rock formations reveal the geological history throughout millions of years. 2 The canyon was formed by the Prairie Dog Town Lighthouse Rock, Palo Duro Canyon, Courtesy Fork Red River, which initially winds along the level of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department surface of the Llano Estacado of West Texas, then suddenly and dramatically runs off the Caprock Escarpment. -

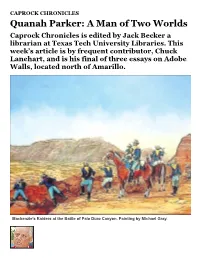

Quanah Parker: a Man of Two Worlds Caprock Chronicles Is Edited by Jack Becker a Librarian at Texas Tech University Libraries

CAPROCK CHRONICLES Quanah Parker: A Man of Two Worlds Caprock Chronicles is edited by Jack Becker a librarian at Texas Tech University Libraries. This week’s article is by frequent contributor, Chuck Lanehart, and is his final of three essays on Adobe Walls, located north of Amarillo. Mackenzie’s Raiders at the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon. Painting by Michael Gray. Chuck Lanehart One of the greatest Native Americans was born on the Caprock, or perhaps elsewhere. In either case, Quanah Parker was a legendary presence on the Texas Plains and beyond. Quanah’s story begins with his mother, Cynthia Ann Parker, a white child who lived with her pioneer family at the East Texas settlement of Fort Parker in what is now Limestone County. In 1836, Comanches attacked, killing her father and several others and capturing 9-year-old Cynthia Ann, along with two women and two other children. Parker’s Fort Massacre drawing published in 1912 in DeShields’ Border Wars of Texas. Cynthia Ann Parker [PUBLIC DOMAIN] Col. Ranald Mackenzie [PUBLIC DOMAIN] The other captives were eventually freed, but Cynthia Ann adopted Comanche ways. She married Noconi Comanche warrior Peta Nocona, and Quanah was born of their union in about 1845. A daughter, Prairie Flower, came later. Although Quanah believed Oklahoma was his birthplace, there is evidence he was born near Cedar Lake, northeast of Seminole, in Gaines County. In 1860 at the Battle of the Pease River — in what is now Foard County — Texas Rangers reportedly killed Quanah’s father and recaptured his mother and Prairie Flower.