OR GREAT BOOK. Figure 10 Explains the Cosmographic System of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ptolemaic System Claudius Ptolemy

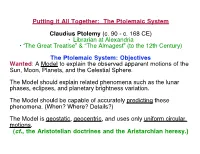

Putting it All Together: The Ptolemaic System Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90 - c. 168 CE) • Librarian at Alexandria • “The Great Treatise” & “The Almagest” (to the 12th Century) The Ptolemaic System: Objectives Wanted: A Model to explain the observed apparent motions of the Sun, Moon, Planets, and the Celestial Sphere. The Model should explain related phenomena such as the lunar phases, eclipses, and planetary brightness variation. The Model should be capable of accurately predicting these phenomena. (When? Where? Details?) The Model is geostatic, geocentric, and uses only uniform circular motions. (cf., the Aristotelian doctrines and the Aristarchian heresy.) The Ptolemaic System Observations • The apparent rotation of the Celestial Sphere • The annual motion of the Sun along the ecliptic • The monthly motion of the Moon The lunar phases and the synodic month Lunar and Solar Eclipses • The motions of the planets on the celestial sphere Direct and retrograde motions Planetary brightness variations Periodicities: The synodic periods Assumptions • A Geostatic cosmology (The Earth does not move.) • Uniform Circular motions (It is a “perfect” universe.) Approaches • The offsets and epicycles introduced by Hipparchus The Ptolemaic System For Inferior Planets (Mercury Venus) Deferent Period is 1 Year; Epicyclic period is the Synodic Period For Superior Planets (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) Deferent Period is the Synodic period; Epicyclic Period is 1 year The Ptolemaic System (“To Scale”) Note: Indicated motions are with respect to the Celestial Sphere AGAIN: Problems with the Ptolemaic System Recollect the assumptions • The Earth doesn’t move (“geostatic”) • The Earth is at the center of the universe (“geocentric”) • All motions are circular (... or combinations thereof) • All motions are uniform (.. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

Historical Astronomy

Historical Astronomy (Neolithic record of Moon Phases) Introduction Arguably the history of astronomy IS the history of science. Many cultures carried out astronomical observations. However, very few formed mathematical or physical models based on their observations. It is those that did that we will focus on here, primarily the Babylonians and Greeks. Other Examples At the same time, that focus should not cause us to forget the impressive accomplishments of other cultures. Other Examples ∼ 2300 year old Chankillo Big Horn Medicine Wheel, Observatory, near Lima, Wyoming Peru Other Examples Chinese Star Map - Chinese records go back over 4000 Stonehenge, England years Babylonian Astronomy The story we will follow in more detail begins with the Babylonians / Mesopotamians / Sumerians, the cultures that inhabited the “fertile crescent.” Babylonian Astronomy Their observations and mathematics was instrumental to the development of Greek astronomy and continues to influence science today. They were the first to provide a mathematical description of astronomical events, recognize that astronomical events were periodic, and to devise a theory of the planets. Babylonian Astronomy Some accomplishments: • The accurate prediction of solar and lunar eclipses. • They developed mathematical models to predict the motions of the planets. • Accurate star charts. • Recognized the changing apparent speed of the Sun’s motion. • Developed models to account for the changing speed of the Sun and Moon. • Gave us the idea of 360◦ in a circle, 600 in a degree, 6000 in a minute. Alas, only very fragmentary records of their work survives. Early Greek The conquests of Alexander the Great are oen credited with bringing knowl- edge of the Babylonians science and mathematics to the Greeks. -

Proof of Geocentric Theory E

Proof of geocentric theory E. A. Abdo Abstract: Rejected by modern science, the geocentric theory (in Greek, ge means earth), which maintained that Earth was the center of the universe, dominated ancient and medieval science. It seemed evident to early astronomers that the rest of the universe moved about a stable, motionless Earth. The Sun, Moon, planets, and stars could be seen moving about Earth along circular paths day after day. It appeared reasonable to assume that Earth was stationary, for nothing seemed to make it move. Furthermore, the fact that objects fall toward Earth provided what was perceived as support for the geocentric theory. Finally, geocentrism was in accordance with the theocentric (God-centered) world view, dominant in in the Middle Ages, when science was a subfield of theology. Introduction: The geocentric model created by Greek astronomers assumed that the celestial bodies moving about the Earth followed perfectly circular paths. This was not a random assumption: the circle was regarded by Greek mathematicians and philosophers as the perfect geometric figure and consequently the only one appropriate for celestial motion. However, as astronomers observed, the patterns of celestial motion were not constant. The Moon rose about an hour later from one day to the next, and its path across the sky changed from month to month. The Sun's path, too, changed with time, and even the configuration of constellations changed from season to season. These changes could be explained by the varying rates at which the celestial bodies revolved around the Earth. However, the planets (which got their name from the Greek word planetes, meaning wanderer and subject of error), behaved in ways that were difficult to explain. -

Hestia: the Indo-European Goddess of the Cosmic Central Fire

Hestia: The Indo-European Goddess of the Cosmic Central Fire Marcello De Martino Abstract: The Pythagorean Philolaus of Croton (470-390 BCE) created a unique model of the Universe and he placed at its centre a ‘fire’, around which the spheres of the Earth, the Counter-Earth, the five planets, the Sun, the Moon and the outermost sphere of fixed stars, also viewed as fire but of an ‘aethereal’ kind, were revolving. This system has been considered as a step towards the heliocentric model of Aristarchus of Samos (310-230 BCE), the astronomical theory opposed to the geocentric system, which already was the communis opinio at that time and would be so for many centuries to come: but is that really so? In fact, comparing the Greek data with those of other ancient peoples of Indo-European language, it can be assumed that the ‘pyrocentric’ system is the last embodiment of a theological tradition going back to ancient times: Hestia, the central fire, was the descendant of an Indo-European goddess of Hearth placed at the centre of the religious and mythological view of a deified Cosmos where the gods were essentially personifications of atmospheric phenomena and of celestial bodies. In 1960, an article came out in a scientific journal which specialised in topics which were a bit more eccentric that those of traditional research studies on the history of religions, especially the classical ones. Its title was On the Relation between Early Greek Scientific Thought and Mysticism: Is Hestia, the Central Fire, an Abstract Astronomical Concept?.1 The author was Rudolph E. -

Looking at the Earth from Outer Space: Ancient Views on the Power of Globes” Christian Jacob

“Looking at the Earth from Outer Space: Ancient Views on the Power of Globes” Christian Jacob To cite this version: Christian Jacob. “Looking at the Earth from Outer Space: Ancient Views on the Power of Globes”. Globe Studies. The Journal of the International Coronelli Society, 2002, 49-50, p. 3-17. hal-00131577 HAL Id: hal-00131577 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00131577 Submitted on 16 Feb 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Paper presented at the International Globes Symposium, 19-23 Octobre 2000: Stewart Museum, Montreal. Published in: Globe Studies. The Journal of the International Coronelli Society, 2002, 49-50, pp. 3-17. Looking at the Earth from Outer Space: Ancient Views on the Power of Globes Christian Jacob Globes belong to the history of cartography. But there is something special with them. The making of globes, indeed, is a specific technical process. Globes are three-dimensional artifacts, built from various materials, wood, metal, cardboard, plaster and so on. Their visible spherical surface sometimes hides a sophisticated construction. Globes need a pedestal and machinery allowing them to rotate around an axis. -

Full Text - Nicholas Copernicus, "De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions)," 1543 C.E

Full text - Nicholas Copernicus, "De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions)," 1543 C.E. The text of: Nicholas Copernicus De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions), 1543 C.E. Nicholas Copemicus (1473-1543) That Nicholas Copernicus delayed until near death to publish De revolutionibus has been taken as a sign that he was well aware of the possible furor his work might incite; certainly his preface to Pope Paul III anticipates many of the objections it raised. But he could hardly have anticipated that he would eventually become one of the most famous people of all time on the basis of a book that comparatively few have actually read (and fewer still understood) in the 450 years since it was first printed. Copernicus was bom into a well-to-do mercantile family in 1473, at Torun, Poland. After the death of his father, he was sponsored by his uncle, Bishop Watzenrode, who sent him first to the University of Krakow, and then to study in Italy at the universities of Bologna, Padua and Ferrara. His concentrations there were law and medicine, but his lectures on the subject at the University of Rome in 1501 already evidenced his interest in astronomy. Returning to Poland, he spent the rest of his life as a church canon under his uncle, though he also found time to practice medicine and to write on monetary reform, not to mention his work as an astronomer. In 1514, Copernicus privately circulated an outline of his thesis on planetary motion, but actual publication of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) containing his mathematical proofs did not occur until 1543, after a supporter named Rheticus had impatiently taken it upon himself to publish a brief description of the Copernican system (Narratio prima) in 1541. -

Historical Figures of Astronomy Matching

(Write your answers on a separate sheet of paper.) Historical Figures of Astronomy Matching: Match the historical figure with his contribution to the evolution of astronomy as a science. (Note: choices may be used more than once) a. Copernicus b. Aristotle c. Kepler d. Plato e. Galileo f. Ptolemy g. Eratosthenes h. Tycho i. Philolaus 1. Developed an astronomical model that contained 55 spheres turning at different rates and at different angles to carry the seven known planets across the sky 2. Believed Earth moved around a central fire 3. Discovered four moons circling Jupiter 4. Determined that the orbits of the planets around the sun are ellipses with the sun at one focus 5. Calculated Earth's radius by utilizing the position of the sun in Alexandria and Syrene and the distance between the two cities 6. Believed that the heavens are perfect and must be made up of perfect spheres rotating at constant rates and carrying objects in a circle 7. Proved Ptolemaic theory was invalid because he found no parallax with the discovery of a new star 8. Believed the sizes of the celestial spheres carrying the outer three planets are determined by spacers consisting of two of the five regular solids 9. Developed a heliocentric Universe model with retrograde planetary motion 10. Reported that the Milky Way was made up of many stars too faint to see with the naked eye. 11. Explained planetary motion by describing epicycles, deferents and equants 12. Believed that the Universe was divided into two parts: Earth, imperfect and changeable; and the heavens, perfect and unchanging, a geocentric model used for over 2000 years . -

Aristotle's Rewinding Spheres: Three Options and Their Difficulties

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2005 PREPRINT 289 István M. Bodnár Aristotle’s rewinding spheres: Three options and their difficulties Aristotle's rewinding spheres: Three options and their difficulties István M Bodnár Forthcoming in Apeiron: a journal for ancient philosophy and science <http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/philosophy/apeiron/> Aristotle asserts at 1073b10-13 that he intends to give in Metaphysics XII.8 a definite conception about the multitude of the divine transcendent entities, which function as the movers of the celestial spheres. In order to do so, he describes several celestial theories. First Eudoxus’s, then the modifications of this theory propounded by Callippus, and finally his own suggestion, the introduction of yet further spheres which integrate the celestial spheres into a single overarching scheme. For this, after explaining the spheres providing the component motions of each planet, Aristotle introduces so-called rewinding spheres ( anelittousai ), which perform contrary revolutions 1 to the ones performed by the spheres carrying the planet. The aim of this setup is that the spheres carrying the next planet can be attached directly to the last rewinding sphere of the preceding planet. 2 As a result of the operation of the rewinding 1 I will describe a revolution as contrary to another one if and only if [1] the two revolutions have the same period, [2] are around the same axis, and [3] revolve in an opposite sense. Note that the use of the term `contrary’ is my shorthand. Aristotle rejects in de Caelo I.3 270a12-22 that celestial revolutions could have contraries indeed that is a key component in his proof of the eternity and inalterability of the celestial realm. -

Copernicus' Role in the Scientific Revolution

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2014 Apr 29th, 10:30 AM - 11:45 AM Copernicus’ Role in the Scientific Revolution: Philosophical Merits and Influence on Later Scientists Jonathan Huston Riverdale High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Huston, Jonathan, "Copernicus’ Role in the Scientific Revolution: Philosophical Merits and Influence on Later Scientists" (2014). Young Historians Conference. 11. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2014/oralpres/11 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Huston !1 Copernicus’ Role in the Scientific Revolution: Philosophical Merits and Influence on Later Scientists! Today, Copernicus is one of the most familiar names among Renaissance scientists, but his role in the Scientific Revolution is misunderstood. He is commonly known as the man who introduced the idea of a heliocentric universe, but is not his theory itself that was transformational. In truth, he did very little to advance the proof of his claim. His value is not in what he said, but what it caused later scientists like Brahe, Kepler, Galileo and later Newton, to develop as a result of what he proposed. Copernicus’ work was ultimately most significant because it changed the way people used physics and astronomy to understand the universe. -

Commentariolus Text

Commentariolus by Copernicus From the Nicolaus Copernicus Thorunensis website Our predecessors assumed, I observe, a large number of celestial spheres mainly for the purpose of explaining the planets' apparent motion by the principle of uniformity. For they thought it altogether absurd that a heavenly body, which is perfectly spherical, should not always move uniformly. By connecting and combining uniform motions in various ways, they had seen, they could make any body appear to move to any position. Callippus and Eudoxus, who tried to achieve this result by means of concentric circles, could not thereby account for all the planetary movements, not merely the apparent revolutions of those bodies but also their ascent, as it seems to us, at some times and descent at others, [a pattern] entirely incompatible with [the principle of] concentricity. Therefore for this purpose it seemed better to employ eccentrics and epicycles, [a system] which most scholars finally accepted. Yet the widespread [planetary theories], advanced by Ptolemy and most other [astronomers], although consistent with the numerical [data], seemed likewise to present no small difficulty. For these theories were not adequate unless they also conceived certain equalizing circles, which made the planet appear to move at all times with uniform velocity neither on its deferent sphere nor about its own [epicycle's] center. Hence this sort of notion seemed neither sufficiently absolute nor sufficiently pleasing to the mind. Therefore, having become aware of these [defects], I often considered whether there could perhaps be found a more reasonable arrangement of circles, from which every apparent irregularity would be derived while everything in itself would move uniformly, as is required by the rule of perfect motion. -

Circular Motion, Contrariety, and Aristotle's Unwinding Spheres

DOI 10.1515/apeiron-2013-0011 Apeiron 2013; 46(4): 391–418 Christopher Isaac Noble Topsy-Turvy World: Circular Motion, Contrariety, and Aristotle’s Unwinding Spheres Abstract: In developing his theory of aether in De Caelo 1, Aristotle argues, in DC 1.4, that one circular motion cannot be contrary to another. In this paper, I discuss how Aristotle can maintain this position and accept the existence of celestial spheres that rotate in contrary directions, as he does in his revision of the Eudoxan theory in Metaphysics 12.8. Keywords: Aristotle, De caelo, aether, astronomy, cosmology, circular motion, contrariety Christopher Isaac Noble: LMU-München, Lehrstuhl für Philosophie VI, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München, [email protected] In DC 1.2–4, Aristotle argues for the existence of a celestial element, aether, whose natural motion is in a circle about the center of the cosmos. On the ac- count Aristotle offers there, this celestial body is neither generable nor destruc- tible, and is, indeed, exempt from all change apart from its circular motion, which proceeds eternally. The opening chapters of DC 1 are, however, hardly Aristotle’s last word on the physics of celestial motion. In addition to aether, Aristotle cites soul and unmoved movers as causes of the rotation of the celes- tial spheres, and it is disputed how, and to what extent, these different factors contribute to a single coherent explanation of celestial motion.1 Further – and this is the issue I will discuss in this paper – there is a puzzle about how DC 1.4’s thesis that circular motion has no contrary fits with the astronomical mod- el presented in DC 2 and Metaphysics 12.8, which calls for celestial spheres that 1 In DC 2.2, Aristotle claims that each celestial sphere is ensouled, which suggests that celestial motions represent a special case of animal motion.