Copernicus' Role in the Scientific Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITA of ROBERT HAHN January 2015

CURRICULUM VITA OF ROBERT HAHN January 2015 I. PERSONAL A. Present University Department: Philosophy. II. EDUCATION Ph.D., Philosophy, Yale University, May 1976. M. Phil., Philosophy, Yale University, May 1976. M.A., Philosophy, Yale University, December 1975. B.A., Philosophy, Union College, Summa cum laude, June 1973. Summer Intensive Workshop in Ancient Greek, The University of California at Berkeley, 1973. Summer Intensive Workshop in Sanskrit, The University of Chicago, 1972. III. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2002-present Professor of Philosophy, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale 1988-2001 Associate Professor of Philosophy, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. 1982-1987 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. 1981-1982 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Denison University. 1978-1981 Assistant Professor of Philosophy and the History of Ideas, Brandeis University. 1979-1981 Assistant Professor, Harvard University, Extension. 1980 (Spring) Visiting Professor, The American College of Greece (Deree College), Athens, Greece. 1980 (Summer) Visiting Professor, The University of Maryland: European Division, Athens, Greece (The United States Air Force #7206 Air Base Group). 1977-1978 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, The University of Texas, Arlington. 1977 (Spring) Lecturer in Philosophy, Yale University. 1976 (Fall) Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Philosophy, The University of California at Berkeley. IV. TEACHING EXPERIENCE A. Teaching Interests and Specialties: History of Philosophy, History/Philosophy -

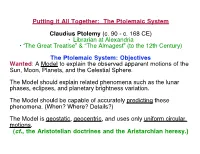

The Ptolemaic System Claudius Ptolemy

Putting it All Together: The Ptolemaic System Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90 - c. 168 CE) • Librarian at Alexandria • “The Great Treatise” & “The Almagest” (to the 12th Century) The Ptolemaic System: Objectives Wanted: A Model to explain the observed apparent motions of the Sun, Moon, Planets, and the Celestial Sphere. The Model should explain related phenomena such as the lunar phases, eclipses, and planetary brightness variation. The Model should be capable of accurately predicting these phenomena. (When? Where? Details?) The Model is geostatic, geocentric, and uses only uniform circular motions. (cf., the Aristotelian doctrines and the Aristarchian heresy.) The Ptolemaic System Observations • The apparent rotation of the Celestial Sphere • The annual motion of the Sun along the ecliptic • The monthly motion of the Moon The lunar phases and the synodic month Lunar and Solar Eclipses • The motions of the planets on the celestial sphere Direct and retrograde motions Planetary brightness variations Periodicities: The synodic periods Assumptions • A Geostatic cosmology (The Earth does not move.) • Uniform Circular motions (It is a “perfect” universe.) Approaches • The offsets and epicycles introduced by Hipparchus The Ptolemaic System For Inferior Planets (Mercury Venus) Deferent Period is 1 Year; Epicyclic period is the Synodic Period For Superior Planets (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) Deferent Period is the Synodic period; Epicyclic Period is 1 year The Ptolemaic System (“To Scale”) Note: Indicated motions are with respect to the Celestial Sphere AGAIN: Problems with the Ptolemaic System Recollect the assumptions • The Earth doesn’t move (“geostatic”) • The Earth is at the center of the universe (“geocentric”) • All motions are circular (... or combinations thereof) • All motions are uniform (.. -

A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Cosmology from Copernicus to Newton

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Scientific transformations: a philosophical and historical analysis of cosmology from Copernicus to Newton Manuel-Albert Castillo University of Central Florida Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Castillo, Manuel-Albert, "Scientific transformations: a philosophical and historical analysis of cosmology from Copernicus to Newton" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5694. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5694 SCIENTIFIC TRANSFORMATIONS: A PHILOSOPHICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF COSMOLOGY FROM COPERNICUS TO NEWTON by MANUEL-ALBERT F. CASTILLO A.A., Valencia College, 2013 B.A., University of Central Florida, 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of Interdisciplinary Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2017 Major Professor: Donald E. Jones ©2017 Manuel-Albert F. Castillo ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to show a transformation around the scientific revolution from the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries against a Whig approach in which it still lingers in the history of science. I find the transformations of modern science through the cosmological models of Nicholas Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton. -

What Did Shakespeare Know About Copernicanism?

DOI: 10.2478/v10319-012-0031-x WHAT DID SHAKESPEARE KNOW ABOUT COPERNICANISM? ALAN S. WEBER Weill Cornell Medical College–Qatar Abstract: This contribution examines Shakespeare’s knowledge of the cosmological theories of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) as well as recent claims that Shakespeare possessed specialized knowledge of technical astronomy. Keywords: Shakespeare, William; Copernicus, Nicolaus; renaissance astronomy 1. Introduction Although some of his near contemporaries lamented the coming of “The New Philosophy,” Shakespeare never made unambiguous or direct reference to the heliocentric theories of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) in his drama or poetry. Peter Usher, however, has recently argued in two books Hamlet’s Universe (2006) and Shakespeare and the Dawn of Modern Science (2010) that Hamlet is an elaborate allegory of Copernicanism, which in addition heralds pre-Galilean telescopic observations carried out by Thomas Digges. Although many of Usher’s arguments are excessively elaborate and speculative, he raises several interesting questions. Just why did Shakespeare, for example, choose the names of Rosenskrantz and Guildenstern for Hamlet’s petard-hoisted companions, two historical relatives of Tycho Brahe (the foremost astronomer during Shakespeare’s floruit)? What was Shakespeare’s relationship to the spread of Copernican cosmology in late Elizabethan England? Was he impacted by such Copernican-related currents of cosmological thought as the atomism of Thomas Harriot and Nicholas Hill, the Neoplatonism of Kepler, and -

The Copernican Revolution (1957) Is a Decidedly Non-Revolutionary Astronomer Who Unwittingly Ignited a Conceptual Revolution in the European Worldview

Journal of Applied Cultural Studies vol. 1/2015 Stephen Dersley The Copernican Hypotheses Part 1 Summary. The Copernicus constructed by Thomas S. Kuhn in The Copernican Revolution (1957) is a decidedly non-revolutionary astronomer who unwittingly ignited a conceptual revolution in the European worldview. Kuhn’s reading of Copernicus was crucial for his model of science as a deeply conservative discourse, which presented in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). This essay argues that Kuhn’s construction of Copernicus and depends on the suppression of the most radical aspects of Copernicus’ thinking, such as the assumptions of the Commentariolus (1509-14) and the conception of hypothesis of De Revolutionibus (1543). After comparing hypo- thetical thinking in the writings of Aristotle and Ptolemy, it is suggested that Copernicus’ concep- tual breakthrough was enabled by his rigorous use of hypothetical thinking. Keywords: N. Copernicus hypothesis, T. S. Kuhn, philosophy of science Stephen Dersley, University of Warwick, Faculty of Social Sciences Alumni, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom, e-mail: [email protected] Kuhn’s Paradigm n The Copernican Revolution, Thomas Kuhn was at pains to construct an image of ICopernicus as a decidedly non-revolutionary astronomer. Kuhn’s model of scientific revolutions, first embodied in The Copernican Revolution and then generalised to the status of a theory in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, conceives of science as be- 100 Stephen Dersley ing, for the majority of the time, a deeply conservative activity. In Kuhn’s model, scien- tists who are engaged in the business of doing every day scientific work do so at the behest of of a reigning paradigm that completely dictates their field of enquiry and functions as an imperceptible intellectual strait-jacket. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

The Copernican Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, and The

The Copernican Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, and the Mechanical Philosophy Conor Mayo-Wilson University of Washington Phil. 401 January 19th, 2017 2 Prediction and Explanation, in particular, the role of mathematics, causation, primary and secondary qualities, microsctructure in prediction and explanation, and 3 Empirical Theories, in particular, the place of the earth in the solar system, the composition of matter, and the causes of terrestial and celestial motion. We're on our way to meeting goal three, but we've got two more to go ::: Course Goals By the end of the quarter, students should be able to explain in what ways the mechanical philosophers agreed and disagreed with Aristotle and scholastics about 1 Epistemology, in particular, the role of testimony, authority, experiment, and logic as sources of knowledge, 3 Empirical Theories, in particular, the place of the earth in the solar system, the composition of matter, and the causes of terrestial and celestial motion. We're on our way to meeting goal three, but we've got two more to go ::: Course Goals By the end of the quarter, students should be able to explain in what ways the mechanical philosophers agreed and disagreed with Aristotle and scholastics about 1 Epistemology, in particular, the role of testimony, authority, experiment, and logic as sources of knowledge, 2 Prediction and Explanation, in particular, the role of mathematics, causation, primary and secondary qualities, microsctructure in prediction and explanation, and Course Goals By the end of the quarter, -

Chapter 2: the Copernican Revolution

1 Name________________________ Unit 2: The Copernican Revolution Vocabulary: Define each term below in a complete sentence on a separate sheet of paper. (Terms that are *, please illustrate) Cosmology Retrograde Motion* Geocentric* Epicycle* Deferent* Ptolemaic Model* Heliocentric* Copernican Revolution Ellipse* Focus* Semi-major axis* Eccentricity Perihelion* Aphelion* Sidereal orbital period Escape Velocity* Inertia Mass Newtonian Mechanics Gravitational Field Stonehenge* Acceleration Gravity* A. Ancient Astronomy 1.Where is Stonehenge? When and who built it? -Salisbury Plain, _______________ -Began 2800-finished __________ B.C. -took 1700 years 2.What was Stonehenge’s purpose? -3-dimensional ____________________, for religious and agriculture purposes -brought in large boulders (up to 50 tons) from miles away 3. What ancient cultures were accomplished in ancient astronomy? -Mayans- ____________Temple in Mexico- used for human sacrifices when the planet Venus appeared -Plains Indians- Big Horn Medicine Wheel, ____________________ -Chinese- 12th century, kept accurate records of comets, and a ‘guest star’ later known as a supernova, visible during the __________ -Muslims- a vital link between ancient Greece and the Renaissance (dark ages), saved astronomical data, developed trigonometry, names stars such as Rigel, _____________ and Vega B. The Geocentric Universe 1.What Greek word is the word planet derived from, why did they get this name? -________________—meandering wanderer, stay close to ecliptic, why? 2. Explain the difference between retrograde and prograde motion: -Prograde motion- ___________________ -Retrograde motion- _____________________ 3. What did Aristotle mean by a geocentric universe? -Geo= Earth -___________________________ 4. How was the geocentric Earth explained by epicycle and deferent? -_____________- small orbits -______________- larger orbits C. Model of the Solar System 1.Who was Nicholas Copernicus? -______________________- rediscovered heliocentric model from ancient Greece-Aristarchus 2. -

ASTRO190 HOMEWORK #1, DUE Jan 16 Before Class

ASTRO190 HOMEWORK #1, DUE Jan 16 before class. This homework covers the material of the first day of class. Submit in pdf or text format to [email protected]. Content, conciseness and clarity matter. More difficult questions will be graded with a lighter touch. Contact me (543-7683; [email protected]) if you are stymied. 1. Modern science can trace its history back to some of the earliest Greek philosophers who preceded Socrates and Aristotle, notably Thales of Miletus (624-546 BCE), Anaximander of Miletus (610-546 BCE), Pythagoras* of Saros (570-495 BCE), Democritus of Thrace (460-370 BCE) * Anaximander’s student, known best for his derivation of the relative lengths of lines of triangles Match each of these people with their assertions about the nature of the natural world (Hint: use Wiki). That is, match each name and the letter that identifies their assertion, such as “Pythagoras – (X)”. (One line) a. Deverything can be understood as the result of natural laws b. Trational thinking and the application of hypotheses, not the ancient anthropomorphic gods, is the way to understand the world around us c. Anature is ruled by laws, just like human societies, and anything that disturbs the balance of nature does not last long d. Pthe planets and stars move according to mathematical equations, which correspond to musical notes and thus produce a symphony 2. Science as we know it withered in the Roman Empire and the Dark Ages until the later years of the Renaissance. Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543), Giordano Bruno (1548-1600), Galileo Galilei of Pisa (1564-1642) re-awakened science and gave it prominence (despite the teachings of powerful theists into the 19th century that only God understands how the world works). -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Aristotle And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2012 PREPRINT 422 TOPOI – Towards a Historical Epistemology of Space Pietro Daniel Omodeo, Irina Tupikova Aristotle and Ptolemy on Geocentrism: Diverging Argumentative Strategies and Epistemologies TOPOI – TOWARDS A HISTORICAL EPISTEMOLOGY OF SPACE The TOPOI project cluster of excellence brings together researchers who investigate the formation and transformation of space and knowledge in ancient civilizations and their later developments. The present preprint series presents the work of members and fellows of the research group Historical Epistemology of Space which is part of the TOPOI cluster. The group is based on a cooperation between the Humboldt University and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin and commenced work in September 2008. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Aristotle 5 2.1 Aristotle’s confrontation with the cosmologies of his prede- cessors . 6 2.2 Aristotle’s presentation of his own views . 9 3 Ptolemy 15 3.1 The heavens move like a sphere . 16 3.2 The Earth, taken as a whole, is sensibly spherical . 24 3.3 The Earth is in the middle of the heavens . 24 3.4 The Earth has the ratio of a point to the heavens . 32 3.5 The Earth does not have any motion from place to place . 33 4 Conclusions and perspectives 37 Chapter 1 Introduction This paper aims at a comparison of the different argumentative strategies employed by Aristotle and Ptolemy in their approaches to geocentrism through an analysis of their discussion of the centrality of the Earth in De caelo II, 13-14 and Almagest, I, 3-7. -

Nicolaus Copernicus: the Loss of Centrality

I Nicolaus Copernicus: The Loss of Centrality The mathematician who studies the motions of the stars is surely like a blind man who, with only a staff to guide him, must make a great, endless, hazardous journey that winds through innumerable desolate places. [Rheticus, Narratio Prima (1540), 163] 1 Ptolemy and Copernicus The German playwright Bertold Brecht wrote his play Life of Galileo in exile in 1938–9. It was first performed in Zurich in 1943. In Brecht’s play two worldviews collide. There is the geocentric worldview, which holds that the Earth is at the center of a closed universe. Among its many proponents were Aristotle (384–322 BC), Ptolemy (AD 85–165), and Martin Luther (1483–1546). Opposed to geocentrism is the heliocentric worldview. Heliocentrism teaches that the sun occupies the center of an open universe. Among its many proponents were Copernicus (1473–1543), Kepler (1571–1630), Galileo (1564–1642), and Newton (1643–1727). In Act One the Italian mathematician and physicist Galileo Galilei shows his assistant Andrea a model of the Ptolemaic system. In the middle sits the Earth, sur- rounded by eight rings. The rings represent the crystal spheres, which carry the planets and the fixed stars. Galileo scowls at this model. “Yes, walls and spheres and immobility,” he complains. “For two thousand years people have believed that the sun and all the stars of heaven rotate around mankind.” And everybody believed that “they were sitting motionless inside this crystal sphere.” The Earth was motionless, everything else rotated around it. “But now we are breaking out of it,” Galileo assures his assistant. -

OR GREAT BOOK. Figure 10 Explains the Cosmographic System of The

36 THE "ALMAGEST" OR GREAT BOOK. Figure 10 explains the cosmographic system of the same astronomer. In the centre we see the Earth, externally surrounded by fire [which is precisely opposite to the truth, according to the fundamental principles of modern geology; but the reader will understand that we are not attempting here to expose the errors of Ptolemaus; we confine ourselves to a description of his system]. Above the Earth spreads the first crystalline heaven, which carries and conveys the Moon. In the second and third crystal heavens the planets Mercury and Venus respectively describe their epicycles. The fourth heaven belongs to the Sun ; wherein it traverses the circle known as the ecliptic. The three last celestial spheres include Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Beyond these planets shines the heaven of the fixed stars. It rotates upon itself from east to west, with an inconceivable rapidity and an incalculable force of impulsion, for it is this which sets in motion all the fabulous machine. Ptolemaus places on the extreme confines of his vast Whole the eternal abode of the blessed. Thrice happy they in having no further cause to concern themselves %I c r ~NT about so terrible a system ; a system far from transparent, notwithstand ing all its crystal! S The treatise in which the Greek SU N X astronomer summed up his labours r _N_U remained for generations in high ( favour with the learned, and especi r F; r ally with the Arabs, whose privilegp and renown it is to have preserved intact the precious deposit of the sciences, when the Europe of the N - twelfth and thirteenth centuries was plunged in the night-shadows of the profoundest ignorance.