Michael Dunne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

45 Sierra Lodestar 1-8-14 24 Pg.Qxp

Amador County Calaveras County Calaveras County Calaveras County CHARLES SPINETTA CHATOM VINEYARDS NEWSOME - HARLOW WINE VAL DU VINO WINERY WINERY AND GALLERY 1969 Highway 4, Douglas Flat. Tasting Room & Offices: 403 Main & ALLEGORIE TASTING 12557 Steiner Road, Plymouth Conveniently located just off Street, Murphys ROOM 245-3384 • www.charlesspinettawinery.com Highway 4, Betwen Angels (209)728-9817 www.nhvino.com 634 French Gulch Rd, Murphys Open 9:00 to 4:00 Mon., Camp and Murphys. Mon thru Thurs 12:00pm-5:00pm 432 Main Street, Murphys 209-728-9911 & 209-728-9922 Thurs. and Fri. Visit 9:00 to Open daily 11:00am - 5:00pm Fri thru Sun 11:30am - 5:30pm Open Daily 11:30am - 5:30pm 4:30 on weekends. Closed 736-6500. www.valduvino.com Tuesday and Wednesday. Chatomvineyards.com OPEN for Dinners: Friday & Saturday Nights - 5-10pm CHIARELLA RENNER WINERY WINES 448 Main Street, 431 Main St., Murphys COOPER VINEYARDS Murphys 728-8318. rennerwines.com Tuolumne County Open Fridays, Saturdays & Sundays from Noon to 21365 Shenandoah School Rd., Plymouth, CA 95669 Open noon everyday 5:00pm and Holiday Mondays. chiarellawines.com 209-245-6181 • www.cooperwines.com BRICE STATION Come visit us at our Tasting Room in downtown Stop by and taste our exquisite wines Open for your wine tasting pleasure: Murphys. WINERY 11:00am - 4:45pm, Thursday through Monday for the finer palate! 18212 Main St. Jamestown, CA FOUR WINDS CELLARS (209) 984-19000 DEAVER VINEYARDS 3675 Six Mile Road, Vallecito STEVENOT WINES www.bricestation.com www.deavervineyards.com 736-4766 • Fri - Sun, 11-5 458 Main Street #3, Wine Tasting: Fri., Sat. -

Click, Swirl, Sip? Interest in Online Wine Surges 5 April 2013, by Michelle Locke

Click, swirl, sip? Interest in online wine surges 5 April 2013, by Michelle Locke Online sales have been around for a while, with individual wineries selling wine through their websites, a practice that has become more prevalent as more states relax Prohibition-era laws that had banned alcohol shipments. Today, only seven U.S. states have an outright ban on direct-to-consumer shipping, though some of the states that do allow shipping have various restrictions, and 89 percent of the U.S. population has access to direct-to-consumer sales, according to Steve Gross of the San Francisco-based Wine Institute, a trade association. What's changed is the rise of third-party sites run In this undated publicity product photo courtesy of Club by companies that don't make wine, like Lot18.com, W, three bottles of wine as shown are offered tailored to which offers special deals on wine. These sites got the buyer's taste monthly for $39. by Club W. Online a boost in 2011 when the California Alcohol wine options are everywhere from flash sale sites like Beverage Control officials issued guidelines Lot 18 to Amazon and Facebook's new wine ventures. allowing third-party providers to act as agents in the And now there's a new generation of startups such as Club W, which adds a little algorithm action to your sale of alcohol but requiring wineries to stay in Albarino, using surveys and ratings to figure out what control of the wine, making them responsible for you might like to drink next. -

List of Suppliers As of April 19, 2019

List of Suppliers as of April 19, 2019 1006547746 1 800 WINE SHOPCOM INC 525 AIRPARK RD NAPA CA 945587514 7072530200 1018334858 1 SPIRIT 3830 VALLEY CENTRE DR # 705-903 SAN DIEGO CA 921303320 8586779373 1017328129 10 BARREL BREWING CO 62970 18TH ST BEND OR 977019847 5415851007 1018691812 10 BARREL BREWING IDAHO LLC 826 W BANNOCK ST BOISE ID 837025857 5415851007 1017363560 10TH MOUNTAIN WHISKEY AND SPIRITS COMPANY LLC 500 TRAIL GULCH RD GYPSUM CO 81637 9703313402 1001989813 14 HANDS WINERY 660 FRONTIER RD PROSSER WA 993505507 4254881133 1035490358 1849 WINE COMPANY 4441 S DOWNEY RD VERNON CA 900582518 8185813663 1040236189 2 BAR SPIRITS 2960 4TH AVE S STE 106 SEATTLE WA 981341203 2064024340 1006562982 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS 6560 E WASHINGTON BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900401822 1016418833 220 IMPORTS LLC 3792 E COVEY LN PHOENIX AZ 850505002 6024020537 1008951900 3 BADGE MIXOLOGY 880 HANNA DR AMERICAN CANYON CA 945039605 7079968463 1016333536 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS 534 MONTGOMERY AVE STE 202 OXNARD CA 930360815 8057972127 1039967515 360 GLOBAL WINE COMPANY INC 3 COLUMBUS CIR FL 15 NEW YORK NY 100198716 2128593520 1040217257 3FWINE LLC 21995 SW FINNIGAN HILL RD HILLSBORO OR 971238828 5035363083 1039154000 503 DISTILLING LLC 275 BEAVERCREEK RD STE 149 OREGON CITY OR 970454171 5038169088 1039152554 5STAR ESPIRIT LLC 1884 THE ALAMEDA SAN JOSE CA 951261733 2025587077 1038066492 8 BIT BREWING COMPANY 26755 JEFFERSON AVE STE F MURRIETA CA 925626941 9516772322 1014665400 8 VINI INC 1250 BUSINESS CENTER DR SAN LEANDRO CA 945772241 5106758888 1014476771 88 -

Wine Varietals and Others July 2015

JULY 2015 Please contact tasting rooms directly as these wines may be subject to availability Allegorie Bunting Wine Tasting Room Frog's Tooth Winery Ironstone Vineyards Mineral Wines Twisted Oak Winery 432 Main St, Murphys 397 Main St, Murphys 380 Main St, Ste 5, Murphys 1894 Six Mile Rd, Murphys 769 Dogtown Rd, Angels Camp 363 Main St, Murphys 209-728-9922 209-573-1295 209-728-2700 209-728-1251 209-743-4100 209-728-3000 www.allegoriewine.com www.buntingwinery.com www.frogstooth.com www.ironstonevineyards.com www.mineral-wines.com 4280 Red Hill Rd, Vallecito Artiste-red blend, Petite Baby Bunting, Cuvee Rouge, Barbera, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Cabernet Franc, Meritage, 209-736-9080 Coquette-sparkling wine, Grenache, Marsanne, Fumé Blanc, Grenache, Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Tempranillo, Vino del www.twistedoak.com Rendez-vous red blend, Mourvèdre, Muscat Canelli- Malbec, Marsanne, Meritage, Malbec, Meritage, Merlot, NV Oro, Viognier Albariño, *%#&@!, "Calaveras Tempranillo, Viognier, Zinfandel dessert, Rosé, Roussanne, Pinot Grigio, Tawny Toad- Champagne, Obsession Rosa" Mourvèdre Rosé, Syrah dessert, Viognier Symphony, Old Vine Zinfandel, Newsome-Harlow "Murgatroyd", "Parcel 17", Ayrael Vieux Vineyard & Petite Sirah, Pinot Grigio, Port, 403 Main St, Murphys Petite Sirah, "Pig Stai" port, Winery Chatom Vineyards and Gossamer Cellars Red Obsession, Syrah, 209-728-9817 "River of Skulls" Mourvèdre, 1690 Monge Ranch Rd Winery 90 Rock Creek Rd #9, Viognier www.nhvino.com Syrah, Syrah-Viognier, Wine Varietals and Others -

Garagiste Vaughn Duffy Wines November

Volume 06 Issue 24 Garagiste WINE CLUB [gar-uh-zheest’] noun - A French term used to describe independent, artisan winemakers crafting small batches of wine in garage-type settings and not yet discovered by the mainstream. Vaughn Duffy Wines Owner/Winemaker: Matt Duffy & Sara Vaughn Location: Sonoma County, CA Matt Duffy attended University of California Berkeley and expected to be an English or journalism graduate. Several years after leaving Cal Berkeley, Duffy managed a tasting room at Twisted Oak Winery in the Sierra Foothills AVA. The experience morphed into additional jobs around the winery and Duffy’s course of action changed to the pursuit of the almighty grape. Fast forward to around 2009 and Duffy and his now wife, Sara Vaughn, made the decision to buy one ton of Pinot Noir and turn it into the first release of Vaughn Duffy Wines, a tiny issue of only 150 cases some two years later. “We have grown steadily,” confirmed Matt Duffy. “We will top out at around 2,000 cases this year and we won’t get any larger.” Duffy said that the couple wants to stay small so that they can focus on every aspect of the business, a novel concept in the ever-expanding establishment that is the modern wine industry. All Vaughn Duffy wines are produced at the noted Sonoma custom crush facility called Vinify Wine Services in Santa Rosa where Duffy also serves as the company’s production manager. “What really matters is that everything really works well for us,” informed Duffy. “We were really surprised when we received some of the scores early on. -

Wisconsin Liquor Tax Monthly Taxable Liters 11/1/19

Page 1 of 98 WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE ACCESS LIQUOR TAX SYSTEM TAXABLE LITERS BY RECEIVED DATE BETWEEN 11/01/2019 AND 11/30/2019 CORPORATION NAME SPIRITS WINE UNDER 14% WINE OVER 14% CIDER UNDER 7% TOTALS OUT OF STATE SHIPPER (FF) 1516 IMPORTS LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 22 HUNDRED CELLARS INC 0.00 83.21 16.64 0.00 99.85 26 BRIX LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 3 BADGE BEVERAGE CORPORATION 702.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 702.00 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS AND IMPORTERS LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 8 VINI INC 0.00 61.83 0.00 0.00 61.83 88 EAST BEVERAGE COMPANY 613.30 0.00 0.00 0.00 613.30 9 DRAGON CELLARS LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 A TO Z WINEWORKS LLC 0.00 6,984.00 90.00 0.00 7,074.00 ACCOLADE WINES NORTH AMERICA INC 0.00 8,459.21 1,026.00 0.00 9,485.21 ACKLEY BRANDS LTD 0.00 216.00 0.00 0.00 216.00 ADAM H LEE 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ADAM J RUHLAND 0.00 0.00 0.00 627.00 627.00 ADAMBA IMPORTS INTERNATIONAL INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ADAMS WINERY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ADELLE BROUNSTEIN 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ADELSHEIM VINEYARD LLC 0.00 161.50 0.00 0.00 161.50 ADVANTAGE INTERNATIONAL DISTRIBUTORS INC 0.00 1,848.42 0.00 0.00 1,848.42 AH WINES INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 AIKO IMPORTERS INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 AIRPORT RANCH ESTATES LLC 0.00 684.00 252.00 0.00 936.00 AKA WINES LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALAMBIC INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALBERT BICHOT USA LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALEJANDRO BULGHERONI ESTATE LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Page 2 of 98 WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE -

Radio Guest List

iWineRadio℗ Wine-Centric Connection since 1999 Wine, Food, Travel, Business Talk Hosted and Produced by Lynn Krielow Chamberlain, oral historian iWineRadio is the first internet radio broadcast dedicated to wine iWineRadio—Guest Links Listen to iWineRadio on iTunes Internet Radio News/Talk FaceBook @iWineRadio on Twitter iWineRadio on TuneIn Contact Via Email View My Profile on LinkedIn Guest List Updated February 20, 2017 © 1999 - 2017 lynn krielow chamberlain Amy Reiley, Master of Gastronomy, Author, Fork Me, Spoon Me & Romancing the Stove, on the Aphrodisiac Food & Wine Pairing Class at Dutton-Goldfield Winery, Sebastopol. iWineRadio 1088 Nancy Light, Wine Institute, September is California Wine Month & 2015 Market Study. iWineRadio1087 David Bova, General Manager and Vice President, Millbrook Vineyards & Winery, Hudson River Region, New York. iWineRadio1086 Jeff Mangahas, Winemaker, Williams Selyem, Healdsburg. iWineRadio1085a John Terlato, “Exploring Burgundy” for Clever Root Summer 2016. iWineRadio1085b John Dyson, Proprietor: Williams Selyem Winery, Millbrook Vineyards and Winery, and Villa Pillo. iWineRadio1084 Ernst Loosen, Celebrated Riesling Producer from the Mosel Valley and Pfalz with Dr. Loosen Estate, Dr. L. Family of Rieslings, and Villa Wolf. iWineRadio1083 Goldeneye Winery's Inaugural Anderson Valley 2012 Brut Rose Sparkling Wine, Michael Fay, Winemaker. iWineRadio1082a Douglas Stewart Lichen Estate Grower-Produced Sparkling Wines, Anderson Valley. iWineRadio1082b Signal Ridge 2012 Anderson Valley Brut Sparkling Wine, Stephanie Rivin. iWineRadio1082c Schulze Vineyards & Winery, Buffalo, NY, Niagara Falls Wine Trail; Ann Schulze. iWineRadio1082d Ruche di Castagnole Monferrato Red Wine of Piemonte, Italy, reporting, Becky Sue Epstein. iWineRadio1082e Hugh Davies on Schramsberg Brut Anderson Valley 2010 and Schramsberg Reserve 2007. iWineRadio1082f Kristy Charles, Co-Founder, Foursight Wines, 4th generation Anderson Valley. -

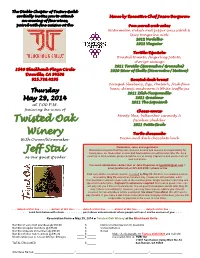

The Diablo Chapter of Tasters Guild Cordially Invites You to Attend

The Diablo Chapter of Tasters Guild cordially invites you to attend Menu by Executive Chef Jason Bergeron an evening of fine wines, paired with fine cuisine at the Pan seared crab cakes Watermelon radish and pepper cress salad & Spicy tangerine aioli 2012 Verdelho 2012 Viognier Tortilla Española Roasted tomato, fingerling potato, chorizo sausage 2011 Torcido (Garancha / Grenache) 3540 Blackhawk Plaza Circle 2010 River of Skulls (Mourvedre / Mataro) Danville, CA 94506 925.736.4295 Roasted duck breast Foraged blueberry, figs, rhubarb, fresh fava bean, shimeji mushroom & White truffle jus Thursday 2011 Zilch Tempranillo May 29, 2014 2011 Graciano 2011 The Sapniard at 7:00 P.M. featuring the wines of Cheese course Moody blue, bellwether carmody & Twisted Oak fiscalini cheddar 2011 Petite Sirah Winery Turtle cheesecake With Owner/Winemaker Pecan and dark chocolate bark Reminders, rules and regulations Attendees recognize that they will consume alcohol and assume all responsibility for Jeff Stai having done so. Moderation in wine and food leads to a healthier and safer life. As a courtesy to all attendees, please avoid the use of strong fragrances and please turn off as our guest speaker your cell phone. For event information contact Gail or John Engstrom at [email protected] = email (preferred) or 925.828.8356 = phone or fax Paid early bird reservations must be received by May 18. All other reservations must be received by May 25, and will be honored only if seats are still available. Each membership is entitled to two seats at the member price. Single members can bring one guest at member price. -

Appellation America Best-Of-Appellation Medal Winners

BEST-OF-APPELLATION This Wine List provided by Appellation America Medal Winning Wines Note: This list has been edited to include PS I Love You Members only. Petite Sirah (List generated on Dec 11, 2008) - 2006 Petite Sirah, Black Rock Ranch (Red Hills Lake County) 750ml $35.00 August Briggs Wines Gold - 2006 Petite Sirah, Frediani (Napa Valley) 750ml $38.00 August Briggs Wines Silver - 2005 Petite Sirah, Fig Tree Vineyard (Napa Valley) 750ml $35.00 Ballentine Vineyards Silver - 2005 Petite Sirah , Estate (Paso Robles) 750ml $23.00 Clayhouse Vineyard Silver - 2005 Petite Sirah, Limited release (Central Coast) 750ml $14.99 Concannon Vineyard Gold - 2005 Reserve Petite Sirah, Estate (Paso Robles) 750ml $25.00 EOS Estate Silver - 2000 Reserve Petite Sirah, Estate (Paso Robles) 750ml $25.00 EOS Estate Silver - 2005 Petite Sirah, Estate (Russian River Valley) 750ml $24.00 Foppiano Vineyards Gold - 1993 La Grande Anniversaire Petite Sirah, Estate (Russian River Valley) Foppiano Vineyards Gold - 2005 Petite Sirah (Columbia Valley) 750ml $30.00 Masset Winery Gold - 2005 Petite Sirah (Lodi) 750ml $22.00 Mettler Family Vineyards Silver - 2001 Petite Sirah (Lodi) 750ml $22.00 Mettler Family Vineyards Silver - 2006 Petite Sirah (Dry Creek Valley) 750ml $32.00 Mounts Family Winery Gold - 2005 Petite Sirah (Dry Creek Valley) 750ml $32.00 Mounts Family Winery Silver - 2005 True Grit (Mendocino) 750ml $29.99 Parducci Wine Cellars Silver - 1987 Petite Sirah (Mendocino County) 750ml $30.00 Parducci Wine Cellars Gold - 2005 Petite Sirah, Family Vineyards (Dry Creek Valley) 750ml $15.00 Pedroncelli Winery Silver - 2005 Royal Punishers (Napa Valley) 750ml $42.00 Robert Biale Vineyards Gold - 1995 Old Vineyards (Napa Valley) Robert Biale Vineyards Gold - 2004 Petite Sirah (California) 750ml $39.00 Silkwood Wines Silver - 2007 Petite Sirah (California) 750ml $39.00 Silkwood Wines Gold - 2006 Petite Sirah (St. -

List of Suppliers As of January 21, 2020

List of Suppliers as of January 21, 2020 1006547746 1 800 WINE SHOPCOM INC 525 AIRPARK RD NAPA CA 945587514 7072530200 1018334858 1 SPIRIT 3830 VALLEY CENTRE DR # 705-903 SAN DIEGO CA 921303320 8586779373 1017328129 10 BARREL BREWING CO 62970 18TH ST BEND OR 977019847 5415851007 1018691812 10 BARREL BREWING IDAHO LLC 826 W BANNOCK ST BOISE ID 837025857 5415851007 1017363560 10TH MOUNTAIN WHISKEY AND SPIRITS COMPANY LLC 500 TRAIL GULCH RD GYPSUM CO 81637 9703313402 1001989813 14 HANDS WINERY 660 FRONTIER RD PROSSER WA 993505507 4254881133 1035490358 1849 WINE COMPANY 4441 S DOWNEY RD VERNON CA 900582518 8185813663 1040236189 2 BAR SPIRITS 2960 4TH AVE S STE 106 SEATTLE WA 981341203 2064024340 1017669627 2 TOWNS CIDERHOUSE 33930SE EASTGATE CIR CORVALLIS OR 97333 5412073915 1006562982 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS 6560 E WASHINGTON BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900401822 1040807186 2HAWK VINEYARD AND WINERY 2335 N PHOENIX RD MEDFORD OR 975049266 5417799463 1008951900 3 BADGE MIXOLOGY 32 PATTEN ST SONOMA CA 954766727 7079968463 1016333536 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS 534 MONTGOMERY AVE STE 202 OXNARD CA 930360815 8057972127 1040217257 3FWINE LLC 21995 SW FINNIGAN HILL RD HILLSBORO OR 971238828 5035363083 1038066492 8 BIT BREWING COMPANY 26755 JEFFERSON AVE STE F MURRIETA CA 925626941 9516772322 1014665400 8 VINI INC 1250 BUSINESS CENTER DR SAN LEANDRO CA 945772241 5106758888 1041559577 88 EAST BEVERAGE COMPANY 533 N MARSHFIELD AVE CHICAGO IL 606226315 6308624697 1015273823 90+ CELLARS 84 CALVERT ST STE 1G HARRISON NY 105283240 7075288500 1040525121 A & M WINE & SPIRITS -

Unified Wine &Grape Symposium

2011 registration & program guide Register TODAY! www.unifiedsymposium.org Sacramento Convention Center Sacramento, California January 25–27, 2011 Exhibits: January 26 & 27 www.unifiedsymposium.org 2011 unified wine& grape symposium Meeting the Needs of the Industry ince the American Society for Enology and Viticulture (ASEV) and the California Association of Winegrape Growers (CAWG) joined S forces to create the Unified Wine & Grape Symposium 17 years ago, it has become the largest wine and grape show in the nation. And while we are proud of the size of the Unified Symposium, it is the show’s established reputation for providing outstanding current news and technical information that we find most rewarding. As one of the industry’s premier gatherings, the Unified Symposium presents a vital platform to focus on the issues shaping our industry today, while interfacing the topics and trends shaping the future of grapegrowing and winemaking. A PROVEN FORMAT By combining a trade show with a broad spectrum of sessions, the Unified Symposium provides attendees direct access to all the latest information — everything from marketing on a budget to understanding wine quality starting in the vineyard to exploring new blends. Unified also provides an excellent forum for active networking with our industry’s suppliers. Winemakers and grapegrowers have a chance not only to renew and make new friendships but also to actively discuss and debate information and ideas that directly influence their work and success. Rep RESENTING THE ENTIRE INDUSTRY The Unified Wine & Grape Symposium organizers have a long and distinguished history of providing vintners and growers with the information they need to remain competitive. -

508 September 2014 Inside This Issue: CQP 3 Contest Corner 6 HRO 9

Issue 508 September 2014 Inside this issue: CQP 3 Contest Corner 6 HRO 9 Guests are always welcome at the NCCC! President’s Report Please join us. Future of the Jug NCCC Meeting You may have noticed that the August and Sep- tember copies of Jug were delayed. Our Jug Monday, October 13th editor, Ian W6TCP, has indicated that he no longer has time to put together the Jug every month due to work commitments. Time: 6:00pm Schmooz, 6:30pm Dinner, If anyone is interested in taking over from Ian, let 7:00pm Program me know. If no one volunteers for this job, it may be a good time to consider alternatives to Program: the Jug. Although the jug is now largely distrib- - 2014 Sweepstakes Bryon N6NUL uted on line, it is still basically the same as it has always been, a monthly newsletter. The trouble with monthly newsletters has always been that Location: news doesn't generally occur in a neat monthly Cattlemens; 250 Dorset Ct, Dixon, CA 95620 cycle. Thus the twin problems of holding urgent (707) 678-5518 news until press time, or a lack of current news to meet the “deadline”. QST has addressed this by being more about “features” (not time specif- ic) and less about “news”. What I am thinking about is setting up a Google group named something like NCCC-announce that would carry important announcements for the club and would be moderated by the board of directors. Having a separate moderated group would prevent post- ings from being lost in the chatter of the reflec- tor.