The Urinal Game and Other Bathroom Customs to Teach the Sociological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ben Whaley: What I Write About When I Write About Gaming

SUBMISSIONS GUIDELINES (/CONTACT) about (/about) CURRENT PRINT ISSUE (/LATEST-PRINT- commentary (/commentary) ISSUE) editorial board (/new-page) PREVIOUS ISSUES (/NEW-PAGE-4) advisory board (/new-page-2) STYLE GUIDE (/NEW-PAGE-1) bulletin of concerned asian scholars, 1968-2001 VISIT US ON TWITTER (https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rcra19/32/4? (HTTPS://TWITTER.COM/CRITICASIANSTDS) CAS (/) nav=toclist) 2019.24: Ben Whaley: What I Write About When I Write About Gaming DECEMBER 3, 2019 I am about twenty-five hours into The World Ends with You, a Japanese role-playing game about a socially-withdrawn teenager who inhabits an afterlife modeled on Tokyo’s youth district Shibuya, when I am thrust into yet another random battle against a group of pink jellyfish monsters. How I hate these jellyfish! They clone themselves when attacked and quickly multiply to overtake your screen. Having already bested this frustrating enemy multiple times during the last hour of play, I sigh and put down my Nintendo DS portable system. Despite what my colleagues and students might think, playing videogames for academic research is indeed hard work! Even if you don’t actively play videogames, you’ve likely heard the argument that classic Japanese games such as Space Invaders (1978) and Donkey Kong (1981) revitalized the North American gaming industry as it stood on the brink of collapse in the 1980s. These games, and others like it, continue to occupy a central place alongside manga (print comics) and animation within Japan’s transmedia ecosystem. Videogames are a pretty big deal in Japan: each year, over 250,000 people attend the annual Tokyo Game Show; Wi-Fi hotspots in Tokyo’s Akihabara electronics district allow passersby to download limited-edition content for their favorite portable games; Mario and Luigi appear on video quiz shows regularly broadcast throughout Tokyo subway cars; and the interactive urinal videogame developed by Sega known as Toylets (2011) even lets men compete in different mini games based on the volume and intensity of their pee. -

Why Menstrual Hygiene Products Should Be Provided for Free in Restrooms

University of Miami Law Review Volume 73 Number 1 Fall 2018 Article 10 10-30-2018 The Bring Your Own Tampon Policy: Why Menstrual Hygiene Products Should Be Provided for Free in Restrooms Elizabeth Montano Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth Montano, The Bring Your Own Tampon Policy: Why Menstrual Hygiene Products Should Be Provided for Free in Restrooms, 73 U. Miami L. Rev. 370 (2018) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol73/iss1/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Bring Your Own Tampon Policy: Why Menstrual Hygiene Products Should Be Provided for Free in Restrooms ELIZABETH MONTANO* Like toilet paper, menstrual hygiene products,1 such as tampons and pads, are necessities for managing natural and unavoidable bodily functions. However, menstrual hygiene products widely receive separate treatment in restrooms across the globe. While it would be absurd today to carry a roll of toilet paper at all times, it is considered necessary and common sense for all menstruators to carry menstrual hy- giene products at all times, for approximately forty years, in case of an emergency. This is the “Bring Your Own * Editor-in-Chief, University of Miami Law Review, Volume 73; J.D. -

Technology Review of Urine-Diverting Dry Toilets (Uddts) Overview of Design, Operation, Management and Costs

Technology Review of Urine-diverting dry toilets (UDDTs) Overview of design, operation, management and costs As a federally owned enterprise, we support the German Government in achieving its objectives in the field of international cooperation for sustainable development. Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 (Bonn) T +49 61 96 79-0 (Eschborn) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 40 53113 Bonn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 F +49 228 44 60-17 66 Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg 1-5 65760 Eschborn, Germany T +49 61 96 79-0 F +49 61 96 79-11 15 E [email protected] I www.giz.de Name of sector project: SV Nachhaltige Sanitärversorgung / Sustainable Sanitation Program Authors: Christian Rieck (GIZ), Dr. Elisabeth von Münch (Ostella), Dr. Heike Hoffmann (AKUT Peru) Editor: Christian Rieck (GIZ) Acknowledgements: We thank all reviewers who have provided substantial inputs namely Chris Buckley, Paul Calvert, Chris Canaday, Linus Dagerskog, Madeleine Fogde, Robert Gensch, Florian Klingel, Elke Müllegger, Charles Niwagaba, Lukas Ulrich, Claudia Wendland and Martina Winker, Trevor Surridge and Anthony Guadagni. We also received useful feedback from David Crosweller, Antoine Delepière, Abdoulaye Fall, Teddy Gounden, Richard Holden, Kamara Innocent, Peter Morgan, Andrea Pain, James Raude, Elmer Sayre, Dorothee Spuhler, Kim Andersson and Moses Wakala. The SuSanA discussion forum was also a source of inspiration: http://forum.susana.org/forum/categories/34-urine-diversion-systems- -

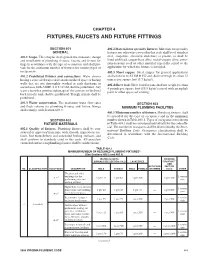

Chapter 4 Fixtures, Faucets and Fixture Fittings

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen CHAPTER 4 FIXTURES, FAUCETS AND FIXTURE FITTINGS SECTION 401 402.2 Materials for specialty fixtures. Materials for specialty GENERAL fixtures not otherwise covered in this code shall be of stainless 401.1 Scope. This chapter shall govern the materials, design steel, soapstone, chemical stoneware or plastic, or shall be and installation of plumbing fixtures, faucets and fixture fit- lined with lead, copper-base alloy, nickel-copper alloy, corro- tings in accordance with the type of occupancy, and shall pro- sion-resistant steel or other material especially suited to the vide for the minimum number of fixtures for various types of application for which the fixture is intended. occupancies. 402.3 Sheet copper. Sheet copper for general applications 401.2 Prohibited fixtures and connections. Water closets shall conform to ASTM B 152 and shall not weigh less than 12 having a concealed trap seal or an unventilated space or having ounces per square foot (3.7 kg/m2). walls that are not thoroughly washed at each discharge in 402.4 Sheet lead. Sheet lead for pans shall not weigh less than accordance with ASME A112.19.2M shall be prohibited. Any 4 pounds per square foot (19.5 kg/m2) coated with an asphalt water closet that permits siphonage of the contents of the bowl paint or other approved coating. back into the tank shall be prohibited. Trough urinals shall be prohibited. 401.3 Water conservation. The maximum water flow rates SECTION 403 and flush volume for plumbing fixtures and fixture fittings MINIMUM PLUMBING FACILITIES shall comply with Section 604.4. -

New Business Ideas Report 2007 , Is an Analysis of Innovative and Never-Seen-Before Business Ideas We’Ve Seen Worldwide This Year

This free 20-pages PDF ebook, New Business Ideas Report 2007 , is an analysis of innovative and never-seen-before business ideas we’ve seen worldwide this year. Clearly, entrepreneurs around the world are often inspired by common underlying consumer trends when they are working to bring their new business ideas to fruition. We hope that you’ll be able to come up with the next big thing after getting to know some of these interesting consumer and business trends behind 2007’s new business ideas. If you want more, be sure to check out our blog at http://www.CoolBusinessIdeas.com . Updated daily with the latest business ideas which we’ve spotted worldwide, we’re sure you’ll find it an enjoyable read. Don’t forget to share this report with your friends and colleagues. We also wanna say thanks to Anita Campbell, for graciously hosting the weekly column New Business Ideas Report over at her website Small Business Trends (http://www.smallbiztrends.com). Once again, this report is brought to you by CoolBusinessIdeas.com. We hope you enjoy it! The CoolBusinessIdeas.com team - Marcel, Steven and Yuelin http://www.coolbusinessideas.com -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This free ebook is brought to you by CoolBusinessIdeas.com Copyright © 2007 CoolBusinessIdeas.com. You may distribute this document freely provided that it is no modified or altered in any way. Disclaimer: The authors of this e-book tried to present the most accurate information to their knowledge at the time of writing. The authors of this book shall not be held responsible for any kind of losses or damages caused by its use and implementation. -

DSA Bulletin BU 17-01-01:Identification Of

BU 17-01-01 BULLETIN: IDENTIFICATION OF SINGLE–USER TOILET FACILITIES AS ALL–GENDER: FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Division of the State Architect (DSA) documents referenced within this publication are available DSA Publications webpages. PURPOSE: This bulletin is a supplement to BU 17-01: Identification of Single-User Toilet Facilities as All- Gender and is provided to assist facility operators and design professionals who design facilities under the jurisdiction of DSA in interpreting the requirements of Health and Safety Code (HSC) 118600. DISCUSSION: HSC 118600 requires: a) All single-user toilet facilities in any business establishment, place of public accommodation, or state or local government agency shall be identified as all-gender toilet facilities by signage that complies with Title 24 of the California Code of Regulations, and designated for use by no more than one occupant at a time or for family or assisted use. b) During any inspection of a business or a place of public accommodation by an inspector, building official, or other local official responsible for code enforcement, the inspector or official may inspect for compliance with this section. c) For the purposes of this section, “single-user toilet facility” means a toilet facility with no more than one water closet and one urinal with a locking mechanism controlled by the user. d) This section shall become operative on March 1, 2017. FOLLOWING IS A LIST OF FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: In applying this statute to existing facilities, how does HSC section 118600 reconcile with the provisions in the California Building Standards Code (CBSC)? According to Assembly analysis: Assembly Bill 1732 does not change existing laws with respect to the number of, specifications for, or other facility requirements for restrooms that a business or entity must comply with under the existing CBC or current local ordinances, but changes the restroom identification and availability of use. -

ADA Design Guide Washrooms & Showers

ADA Design Guide Washrooms & Showers Accessories Faucets Showers Toilets Lavatories Interactive version available at bradleycorp.com/ADAguide.pdf Accessible Stall Design There are many dimensions to consider when designing an accessible bathroom stall. Distances should allow for common usage by people with a limited range of motion. A Dimension guidelines when dispensers protrude from the wall in toilet rooms and 36" max A toilet compartments. 915 mm Anything that a person might need to reach 24" min should be a maximum of 48" (1220 mm) off of 610 mm the finished floor. Toilet tissue needs to be easily within arm’s 12" min reach. The outlet of a tissue dispenser must 305 mm be between 24" (610 mm) minimum and 42" (1070 mm) maximum from the back wall, and per the ANSI standard, at least 24" min 48" max 18" above the finished floor. The ADA guide 610 mm 1220 mm defines “easily with arm’s reach” as being within 7-9" (180–230 mm) from the front of 42" max the bowl and at least 15" (380 mm) above 1070 mm the finished floor (48" (1220 mm) maximum). Door latches or other operable parts cannot 7"–9" 18" min 180–230 mm require tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of 455 mm the wrist. They must be operable with one hand, using less than five pounds of pressure. CL Dimensions for grab bars. B B 39"–41" Grab Bars need to be mounted lower for 990–1040 mm better leverage (33-36" (840–915 mm) high). 54" min 1370 mm 18" min Horizontal side wall grab bars need to be 12" max 455 mm 42" (1065 mm) minimum length. -

Cruising Game Space

CRUISING GAME SPACE Game Level Design, Gay Cruising and the Queer Gothic in The Rawlings By Tommy Ting A thesis exhibition presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Digital Futures Toronto Media Arts Centre 32 Lisgar Street., April 12, 13, 14 Toronto, Ontario, Canada April 2019 Tommy Ting 2019 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Copyright Notice Author’s Declaration This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. You are free to: Share – copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt – remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the follower terms: Attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. NonCommericial – You may not use the material for commercial purposes. ShareAlike – If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute you contributions under the same license as the original. -

Menstrual Hygiene Matters Training Guide for Practitioners Acknowledgements

Menstrual hygiene matters Training guide for practitioners Acknowledgements This training guide was produced by Thérèse Mahon and Sue Cavill at WaterAid and jointly funded by the Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) consortium and WaterAid. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sarah House, independent consultant, and Bethany Caruso, Emory University, in designing sessions. Sessions have been adapted from resources published by WaterAid, Loughborough University’s Water, Engineering and Development Centre (WEDC)1, and the International HIV Alliance2. We would also like to thank Sara Liza Baumann of Old Fan Films, who produced and directed the short film Adolescent school girls in Bangladesh on managing menstruation, and WaterAid India / Vatsalya, who produced the film Making invisible, the visible, for their kind permission to use these films. The editorial contribution of Richard Steele is highly appreciated. The sessions are based on the resource book Menstrual hygiene matters (www.wateraid.org/mhm) a comprehensive resource to improve menstrual hygiene management around the world. Menstrual hygiene matters was produced at WaterAid by Sarah House, Thérèse Mahon and Sue Cavill, with inputs from a wide range of individuals and organisations. The resource was jointly funded by SHARE and WaterAid and co-published by 18 organisations. For full details and to download the resource and the training guide please visit www.wateraid.org/mhm The Menstrual hygiene matters resource book and training guide were -

Part 3: Toilet Design Considerations: Micro Level

PLANNING FOR PUBLIC TOILETS PART 3: MICRO LEVEL: TOILET DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS: Inclusive Design for Different Types of User Groups ' To a good doctor there is no physical or mental aspect of his patient which should embarrass him. He may be worried or shocked by what his diagnosis reveals, but if he's any good, he is not embarrassed. Correspondingly, therefore, there should be no type of building, and no human function related to it which should embarrass the architect!' (Architects Journal, 1953, No.117). This section looks at the 'micro' level of detailed toilet design. However, the emphasis is upon principles, and upon 'seeing' how the different components of the toilet cubicle 'work' together, because, as they say, 'the devil is in the detail'. The emphasis is again upon the user, the range of user types, and the social and qualitative factors involved, rather than upon the technical plumbing and engineering aspects dealt with elsewhere in this course programme. There is also a longer optional explanation of the issues in the second part of the paper. A PowerPoint accompanies and illustrates Part 3. Part 3 is longer because detailed issues are so important. A fuller bibliography, list of references is given at the end. In fact Part 3 may be used as a module in its own right on inclusive design. People are Important There are many detailed design guides on the precise dimensions and locations of rails, toilet pans, washbasins, mirrors etc and so it is not the purpose of this chapter to give precise guidance on these. 'The problem' is that some toilet manuals deal with each component without seeing how they inter-relate with each other spatially. -

Public Toilets the Implications In/For Architecture by Allaa Mokdad Advisor Deirdre Hennebury

Public Toilets The Implications In/For Architecture By Allaa Mokdad Advisor Deirdre Hennebury A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in The Lawrence Technological University [2017-2018] Acknowledgments Thank you to my advisor Dr Deirdre Hennebury for all the guid- ance and support in this research inquiry; and my mom and dad and the rest of the Mokdads for all their support during the process. Preface “The toilet is the fundamental zone of interac- tion-on the most intimate level-between humans and architecture. It is the architectural space in which bodies are replenished, inspected, and culti- vated, and where one is left alone for private re- flection- to develop and affirm identity” - Koolhaas, 2014 Content Introduction 1 Abstract 2 Research Method 3 Nomenclature 4 Guiding Questions Theory 5-6 Public Toilet 7 Public 8 Private 9 Toilet Analysis 10 Introduction 11-12 Timeline 13 Definitions 14-24 London 25-31 Paris 32-38 New York 39 Conclusion 40-41 References Abstract A reflection of societal values, the public toilet is a politicized space that provides sanitation in the public realm. In addition to its role in sup- porting a basic human need through sanitation provision, the public toilet is also a space that provides solidarity in the face of congestion, a place where one develops and affirms identity [Koolhaas, 2014]. In the nineteenth century through the twen- ty-first century, the public toilet has shifted from an external urban condition to an interiorized urban issue. It once stood as a symbol of moder- nity in the congested streets of industrial cities, and progressed to be prominently featured in ac- cessibility debates. -

Janitorial SCOTT® Personal Seats Are Flushable and Offer Sanitary Protection, Help Reduce Litter •• Screen with Block Deodorizes for up to 30 Days and Clogging

Toilet Seat Covers & Accessories, Restroom Care 12–17 Toilet Seat Covers & Dispensers Restroom Deodorants HOSPECO Toilet Seat Covers Non-Para Urinal Blocks • Non-Para deodorant blocks are ideal for use with vinyl Health Gards® urinal screens • Does not contain para-dichlorobenzene Part No. Mfg. No. Color Style Pkg. Qty. 0608943 Green-5000 White 1/2 Fold 250 (PDCB), which is a known carcinogen 665072- HG-5000 White Quick 250 • Cleans and deodorizes toilet bowls for up 131448 Dissolving to 30 days • Non-staining- no water color change • Nontoxic, biodegradable ® Safe-t-Gard 1/2 Fold Toilet Seat Part No. Mfg. No. Fragrance Color Style 0610059 04901 Cherry Red Urinal Covers and Dispenser 0610060 04905 Citrus Blue Urinal • "No Touch" feature minimizes cross- contamination Deodorant Blocks • Dispenses highly dispersible seat covers to reduce clogs caused by the use of costly Scented deodorant blocks eliminate odors at alternatives, such as towels or tissues their source. Works up to 30 days. Available in • Durable plastic dispenser with double-pack a 4 oz. block for the urinal or a 4 oz. hanging loading feature is easy to install and cost- block for the toilet effective to maintain Part No. Mfg. No. Color Style Pkg. Qty. Part No. Mfg. No. Fragrance Color Style 0611447 47046 White 1/2 Fold 250 615135-131487 06411 Cherry Pink Urinal 0611802 47047 White 1/4 Fold 200 615136-131487 08411 Cherry Pink Urinal with Hanger Part No. Mfg. No. Color Material 0611448 57748 Black Plastic Unitab® Non-Para Block Urinal Screens Scott® Toilet Seat Covers and Part No. Mfg.