Why Menstrual Hygiene Products Should Be Provided for Free in Restrooms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SANITATION by COMPOSTING Sanitation Developed in Post-Earthquake Haiti in 2010 and 2011 by Givelove.Org

SANITATION BY COMPOSTING Sanitation developed in post-earthquake Haiti in 2010 and 2011 by GiveLove.org. An abbreviated version of this paper was submitted to the International Perspectives on Water and the Environment 2012 Conference in Marrakesh, Morocco. Joseph Jenkins, September 20, 2011 President, Joseph Jenkins, Inc., 143 Forest Lane, Grove City, PA 16127 USA [email protected]; CompostSanitation.com ABSTRACT: Compost toilets can take many forms. One such toilet, the “humanure” toilet, is designed to simply collect and re- cycle human excreta, which includes fecal material, urine and toilet paper, along with a carbon-based cover material, via an odor-free, heat-producing organic mass. The organic compost mass is created away from the toilet in a separate compost bin, not in the toilet itself. The thermophilic and aging phases in the compost bin render the organic material hygienically safe by destroying pathogenic organisms. The final product, humus, is excellent for growing food. Because the toilets themselves are not utilized either for the composting process or for storage of toilet material, they are inexpensive and simple in design and implementation. They recycle organic materials and do not produce or dispose of waste. They create no environmental pollution when properly managed. They require no piped water, no electricity, no venting, no hole in the ground and no drain. When managed correctly, they do not breed flies or produce unpleasant odors and can therefore be located indoors, even in intimate settings. They can -

Leave No Trace Outdoor Skills & Ethics

ISLE ROYALE NATIONAL PARK Leave No Trace Outdoor Skills & Ethics Leave No Trace Outdoor Skills and Ethics ISLE ROYALE NATIONAL PARK Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics November, 2004 Leave No Trace — Isle Royale National Park Skills & Ethics 1 Wildland Ethics "Ethical and moral questions and how we answer them may determine whether primal scenes will continue to be a source of joy and comfort to future generations. The decisions are ours and we have to search our minds and souls for the right answers..." "The real significance of wilderness is a cultural matter. It is far more than hunting, fishing, hiking, camping or canoeing; it has to do with the human spirit." —Sigurd F. Olson ...and so we visit wild places to discover ourselves, to let our spirits run with the graceful canoe and journey through the beckoning forests. The wilderness is good for us. It enables us to discover who we really are, and to explore who we are really meant to be. It is the nature of wild places that gives us the space to slow the pace of our lives, to becalm the storms of everyday life, to gain perspective on the things we truly value. Sigurd Olson needed wild places...they gave much to him, as they do to us—and, so, we should be eager to give back. Our favorite places— those whose forests have welcomed us, whose lakes have refreshed us, whose sunsets have inspired awe—are not ours alone. They are a treasured resource, there for the good of all who seek their own true spirit through solitude and adventure. -

Pink Is the New Tax

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Communication Senior Capstones Senior Projects Fall 2020 Pink Is The New Tax Eliana Burns Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/senior_comm Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Eliana, "Pink Is The New Tax" (2020). Communication Senior Capstones. 1. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/senior_comm/1 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Senior Projects at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Senior Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eliana Burns Humboldt State University 2020 Department of Communications Pink Is The New Tax 1 Historically women in America have made colossal advances that have proven they are just as capable as men. Women had fought and continued to challenge the system since 1919 with the 19th Amendment giving them a right to vote. However, even with this crucial progression, womens’ oppression can be found all around us only in much more subtle ways such as “ the pink tax”. As of 2020 there are currently no federal laws to outlaw companies from charging different prices depending on which gender they are meant to be marketed to. This rhetorical analysis will first address the concept of gendered products, how the tax benefits from these products, and why gendering of products reinforce gender discrimination and stereotypes. A brief explanation as to why the tax is nicknamed “the tampon tax” is included. -

TBN #19 Become Shower Cubicles

Urban WASH Lessons Learned from Post- Earthquake Response in Haiti Large-scale urban WASH programming requires different approaches to those normally employed in Oxfam emergency response activities. This paper examines the lessons learned from the WASH response to the Haiti earthquake in January 2010. The paper also gives practical case studies of some of the success and failures from the WASH activities, undertaken in a very high-density urban/peri-urban context. Introduction Oxfam’s WASH response At the height of the emergency response, Oxfam GB was The main WASH activities undertaken in the earthquake supporting 149,613 people1 with water, sanitation and response in Port-au-Prince included: hygiene promotion in more than 46 sites in the Port-au- Water trucking & distribution Prince area. 18 Camps had populations greater than Water system rehabilitation & community 1,000 people, while the largest camp, Petionville Golf management Course, had a population in excess of 50,000 people. The smallest site, Santo 14-B had a population of 482. On-site sanitation and excreta management Waste collection & removal Location # Project Sites Population Debris collection, removal and processing Delmas 14 67,425 Community mobilisation Carrefour 14 38,718 Hygiene promotion & NFI Distributions Institutional support to the WASH sector Carrefour Feuilles 5 7,950 This has been achieved through a variety of approaches, Croix de Bouquet 11 26,320 including direct implementation through Oxfam teams, working through partners (both INGOs and national Corail 2 9,200 NGOs), and through direct support to the national WASH institutions and the WASH Cluster. Many areas, such as Carrefour Feuilles, Carrefour and Delmas, lack any formal urban planning process and have Oxfam has created a number of innovative relationships high population densities. -

Humanure Sanitation the “No Waste, No Pollution, Nothing to Dispose Of” Toilet System

Humanure Sanitation The “no waste, no pollution, nothing to dispose of” toilet system. Author: Joseph Jenkins, Joseph Jenkins, Inc., 143 Forest Lane, Grove City, PA 16127 USA; [email protected]; http://www.humanurehandbook.com ABSTRACT: Humanure toilets are designed to collect human excreta, including fecal material and urine together without separation, along with a carbon (plant cellulose-based) cover material, for the purpose of achieving an odor-free thermophilic (heat-producing) organic mass. The thermophilic phase renders the organic material hygienically safe by destroying pathogenic organisms, thereby creating a final product, humus, which is suitable for growing food. These toilets are inexpensive and very simple in design and implementation. They do not produce or dispose of waste and they create no environmental pollution. This study looks at various humanure systems in the United States. KEYWORDS: compost toilet, humanure, Joseph Jenkins, sanitation, thermophilic Introduction: What is "Humanure Sanitation"? The humanure sanitation system is a compost toilet system designed and intended to promote the thermophilic composting of human excrement. Human excreta, including fecal material and urine, are not considered waste materials that need to be disposed of. Instead, they are considered resource materials that must be recycled and reclaimed for reuse. When properly used and managed, a humanure toilet system requires virtually no water, produces no waste, creates no environmental pollution, attracts no flies, costs very little, requires no urine diversion, and produces no odor. Instead of waste, the toilet produces humus, a valuable resource that can safely grow food for human beings. It can be constructed for very little money or no money at all if recycled materials are used. -

The Journal of the New Alchemists 3

Journal of the New Alchemists 3 Table of Contents NEW ALCHEMY Looking Back - Na ncy jack Todd 7 The Trash Fish Cook Book - Bill McLarney and Bryce Butler 15 ENERGY An Advanced Sail-Wing for Water-Pumping Windmills - Earle Barnhart 25 Savonius Rotor - Earle Barnhart 27 Solar Collector for Heating Water - Earle Barnhart 30 Earth Breath : Wind Power -jim Bukey 32 LAND AND ITS USE An Ark for Prince Edward Island -john Todd 41 The Shape of Things to Come: The Architects' View - Ole Hammarlund and David Bergmark 44 Confessions of a Novice Compostor - Tyro ne Cashman 45 Our Gardens... and Our Rabbits - Hilde Atema Maingay 48 Further Experiments in the Irrigation of Garden Vegetables with Fertile Fish Pond Water - William 0. McLarney 53 The World in Miniature - John Todd 54 AQUACULTURE Midge Culture - William 0. McLarney, joseph S. Levine and Marcus M. Sherman 80 A New Low - Cost Method of Sealing Fish Pond Bottoms- William 0. McLarney and ]. Robert Hu nter 85 Cultivo Experimental de Peces en Estanques - Anibal Pa tino R. 86 EXPLORATIONS Populist Manifesto .... for Poets with Love - Lawrenc,e Ferlinghetti 94 Meditation on the Dark Ages, Past and Present - William Irwin Thompson 96 Self-Health: Exploring Alternatives in Personal Health Services -Nancy Milia, Ruth Hubbard 102 Women and Ecology - Nancy ja ck Todd 107 .. · . : f ; �--... .. · . : · · · . .. · . · · . 0 'H:., i,�··®: · . ·�· i/i... ' to Restnre the lands, Protect t;he Seas, And Inform "Gho Eart"h8 SreCJIU'ds The New Alchemy Institute is a small, international organization fo r research and education on behalf of humanity and the planet. -

Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices

SEI - Africa Institute of Resource Assessment University of Dar es Salaam P. O. Box 35097, Dar es Salaam Tanzania Tel: +255-(0)766079061 SEI - Asia 15th Floor, Witthyakit Building 254 Chulalongkorn University Chulalongkorn Soi 64 Phyathai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel+(66) 22514415 Stockholm Environment Institute, Project Report - 2011 SEI - Oxford Suite 193 266 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 7DL UK Tel+44 1865 426316 SEI - Stockholm Kräftriket 2B SE -106 91 Stockholm Sweden Tel+46 8 674 7070 SEI - Tallinn Lai 34, Box 160 EE-10502, Tallinn Estonia Tel+372 6 276 100 SEI - U.S. 11 Curtis Avenue Somerville, MA 02144 USA Tel+1 617 627-3786 SEI - York University of York Heslington York YO10 5DD UK Tel+44 1904 43 2897 The Stockholm Environment Institute Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and SEI is an independent, international research institute.It has been engaged in environment and development issuesat local, national, Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices regional and global policy levels for more than a quarterofacentury. SEI supports decision making for sustainable development by Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project bridging science and policy. Marianne Kjellén, Chibesa Pensulo, Petter Nordqvist and Madeleine Fogde sei-international.org Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project Marianne Kjellén, Chibesa Pensulo, Petter Nordqvist and Madeleine Fogde Stockholm Environment Institute Kräftriket 2B 106 91 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 674 7070 Fax: +46 8 674 7020 Web: www.sei-international.org Director of Communications: Robert Watt Publications Manager: Erik Willis Layout: Alison Dyke Cover Photo: © Joachim Huber This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes, without special per- mission from the copyright holder(s) provided acknowledgement of the source is made. -

The Status of Faecal Sludge Management in Eight Southern and East African Countries

THE STATUS OF FAECAL SLUDGE MANAGEMENT IN EIGHT SOUTHERN AND EAST AFRICAN COUNTRIES May 2015 Prepared for the Sanitation Research Fund for Africa (SRFA) Project of the Water Research Commission and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation WRC Report No. KV 340/15 ISBN 978-1-4312-0685-8 THE STATUS OF FAECAL SLUDGE MANAGEMENT IN EIGHT SOUTHERN AND EAST AFRICAN COUNTRIES DISCLAIMER This report was compiled from country reports submitted by research teams involved in the Sanitation Research Fund for Africa (SRFA) Project. This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Further, the WRC, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the service provider take no responsibility for any inaccuracies or undisclosed sources from these country reports. © Water Research Commission 191 Anderson Street Northcliff 2195 Tel: 27 (0) 11 476 5915 Fax: 0866498600 Cell number: 27 (0)834606832 E-mail: [email protected] The publication of this report emanates from a project entitled The Status of Faecal Sludge Management in Eight Southern and East African Countries (WRC Report No. K8/1100/11) WRC Report No. KV 340/15 ISBN 978-1-4312-0685-8 01 THE STATUS OF FAECAL SLUDGE MANAGEMENT IN EIGHT SOUTHERN AND EAST AFRICAN COUNTRIES Executive Summary Background Sub-Saharan Africa still lags behind in achieving the Millennium Development Goals for sanitation. In 2012, 644 million people in sub-Saharan Africa, that is 70% of the population, used an unimproved toilet facility or resorted to open defecation (WHO/UNICEF, 2014). -

FLOW (Finding Lasting Options for Women) Multicentre Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Tampons with Menstrual Cups

Research | Web exclusive FLOW (finding lasting options for women) Multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing tampons with menstrual cups Courtney Howard MD CCFP(EM) Caren Lee Rose MSc Konia Trouton MD CCFP MPH Holly Stamm MD CCFP Danielle Marentette MD CCFP Nicole Kirkpatrick MD CCFP(EM) Sanja Karalic MD CCFP MSc Renee Fernandez MD CCFP Julie Paget MD CCFP Abstract Objective To determine whether menstrual cups are a viable alternative to tampons. Design Randomized controlled trial. EDITOR’S KEY POINTS Setting Prince George, Victoria, and Vancouver, BC. • Patients are increasingly asking physicians about more environmentally friendly Participants A total of 110 women aged 19 to 40 years who had previously alternatives to disposable menstrual used tampons as their main method of menstrual management. management products, particularly menstrual cups, and about their Intervention Participants were randomized into 2 groups, a tampon group effectiveness compared with tampons. and a menstrual cup group. Using online diaries, participants tracked 1 Although the safety and efficacy of menstrual cycle using their regular method and 3 menstrual cycles using menstrual cups have been studied the method of their allocated group. previously, a randomized controlled trial comparing cups with tampons has never Main outcome measures Overall satisfaction; secondary outcomes been done. included discomfort, urovaginal infection, cost, and waste. • This study compared the experiences of Results Forty-seven women in each group completed the final survey, 5 of women using only tampons with women whom were subsequently excluded from analysis (3 from the tampon group using only menstrual cups over a period and 2 from the menstrual cup group). -

WASH MHM Resource Guide 2015.Pdf

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene and Menstrual Hygiene Management: A Resource Guide WASH Advocates December 2015 Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) play a large role in the lives of adolescent girls and women, both biologically and culturally. Gender equity becomes an issue when women and girls lack access to WASH facilities and appropriate hygiene education, affecting a girl’s education, sexual and reproductive health, and dignity. Lack of adequate facilities and materials for menstrual hygiene has been linked to absenteeism of girls from school during their periods.1 Many may permanently drop out of school with the onset of puberty if the toilet facilities are not clean or do not provide privacy to girls while they are menstruating.2 Menstruation is a taboo subject in many cultures and can create stigma, shame, and silence among young girls, which often continues into adulthood and perpetuates the cycle of gender inequality. Around the world, girls try to keep their menstruation a secret while they are in school. Without adequate sanitation facilities, girls are unable to manage their menstruation safely, hygienically, and with dignity and will be unlikely to use the facilities if there is no guarantee to privacy. Due to social and WASH-related issues, many girls choose to stay home during their menstruation instead of having to manage their period at school.3 Other times, girls do attend school but face challenges such as leakage, odor, discomfort, or difficulty concentrating. When child-friendly educational programs that raise awareness about menstrual hygiene management (MHM) are coupled with safe, private, and single-gender sanitation facilities; an accessible water supply; and a means for safe disposal of menstrual waste, they can help alleviate the burden girls face at school during menstruation.4 Access to these facilities at home and at health clinics is also important to allow women and girls a safe means to manage their menstruation at all times. -

Technology Review of Urine-Diverting Dry Toilets (Uddts) Overview of Design, Operation, Management and Costs

Technology Review of Urine-diverting dry toilets (UDDTs) Overview of design, operation, management and costs As a federally owned enterprise, we support the German Government in achieving its objectives in the field of international cooperation for sustainable development. Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 (Bonn) T +49 61 96 79-0 (Eschborn) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 40 53113 Bonn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 F +49 228 44 60-17 66 Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg 1-5 65760 Eschborn, Germany T +49 61 96 79-0 F +49 61 96 79-11 15 E [email protected] I www.giz.de Name of sector project: SV Nachhaltige Sanitärversorgung / Sustainable Sanitation Program Authors: Christian Rieck (GIZ), Dr. Elisabeth von Münch (Ostella), Dr. Heike Hoffmann (AKUT Peru) Editor: Christian Rieck (GIZ) Acknowledgements: We thank all reviewers who have provided substantial inputs namely Chris Buckley, Paul Calvert, Chris Canaday, Linus Dagerskog, Madeleine Fogde, Robert Gensch, Florian Klingel, Elke Müllegger, Charles Niwagaba, Lukas Ulrich, Claudia Wendland and Martina Winker, Trevor Surridge and Anthony Guadagni. We also received useful feedback from David Crosweller, Antoine Delepière, Abdoulaye Fall, Teddy Gounden, Richard Holden, Kamara Innocent, Peter Morgan, Andrea Pain, James Raude, Elmer Sayre, Dorothee Spuhler, Kim Andersson and Moses Wakala. The SuSanA discussion forum was also a source of inspiration: http://forum.susana.org/forum/categories/34-urine-diversion-systems- -

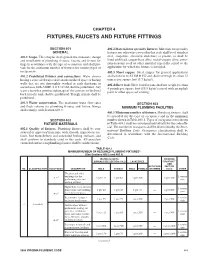

Chapter 4 Fixtures, Faucets and Fixture Fittings

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen CHAPTER 4 FIXTURES, FAUCETS AND FIXTURE FITTINGS SECTION 401 402.2 Materials for specialty fixtures. Materials for specialty GENERAL fixtures not otherwise covered in this code shall be of stainless 401.1 Scope. This chapter shall govern the materials, design steel, soapstone, chemical stoneware or plastic, or shall be and installation of plumbing fixtures, faucets and fixture fit- lined with lead, copper-base alloy, nickel-copper alloy, corro- tings in accordance with the type of occupancy, and shall pro- sion-resistant steel or other material especially suited to the vide for the minimum number of fixtures for various types of application for which the fixture is intended. occupancies. 402.3 Sheet copper. Sheet copper for general applications 401.2 Prohibited fixtures and connections. Water closets shall conform to ASTM B 152 and shall not weigh less than 12 having a concealed trap seal or an unventilated space or having ounces per square foot (3.7 kg/m2). walls that are not thoroughly washed at each discharge in 402.4 Sheet lead. Sheet lead for pans shall not weigh less than accordance with ASME A112.19.2M shall be prohibited. Any 4 pounds per square foot (19.5 kg/m2) coated with an asphalt water closet that permits siphonage of the contents of the bowl paint or other approved coating. back into the tank shall be prohibited. Trough urinals shall be prohibited. 401.3 Water conservation. The maximum water flow rates SECTION 403 and flush volume for plumbing fixtures and fixture fittings MINIMUM PLUMBING FACILITIES shall comply with Section 604.4.