Spanish Additions to the Cowboy Lexicon from 1850 to the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPEC WLJ V89 N09.Pdf (12.42Mb)

The National Livestock Weekly December 7, 2009 • Vol. 89, No. 09 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” Web site: www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication INSIDE WLJ House plan would extend death tax for 2010 Congress was set to vote last said exempting estates as large government borrowing. Committee which is responsible week to block the expiration of the as $3.5 million from the tax “will House Republicans continue to for writing tax laws. Camp said so-called “Death Tax.” Prior to the protect all but the wealthiest battle the change, opposing any he is concerned that the $3.5 vote, the tax on estates was to end Americans.” The current law was tax at all on estates passed from million exemption would not be in 2010 before coming back in 2011 the result of a compromise reached one generation to the next. indexed for inflation, meaning at an even higher rate. However, in 2001 as Republicans worked to “I don’t think death in and of more and more estates would be congressional action on H.R. 4154, eliminate the tax entirely, how- itself should be a taxable event,” subject to the tax in the future. which was introduced by Rep. Earl ever, they were forced to settle for said Rep. Dave Camp, R-MI, who Currently, the tax affects few Pomeroy, D-ND, will extend the 45 a gradual reduction and a one- is also the ranking member of estates. In 2009, about 5,500 SECTIONSECTION TTWO—ThisWO—This week’sweek’s edi-edi- tion of WLJ includes the quarterly percent tax on estates valued in year repeal. -

Chuckwagon-Cooking-School

http://www.americancowboy.com/blogs/south-texas-cowboy/essay-contest-winner-heads- chuckwagon-cooking-school ESSAY Contest Winner - Heads to Chuckwagon Cooking School American Cowboy BY ROGER EDISON 3/21/2012 Kent and Shannon Rollins operate one of the most unique, as well, one of a kind culinary schools in the nation. Each spring and fall, they hold their semi annual Chuck Wagon Cooking School at the Red River Ranch in Byers, Texas. The school teaches students the culinary art of cowboy cooking using cast iron dutch ovens, all in an authentic setting working from a restored 1876 Studebaker wagon. Sourdough biscuits, baking pie crust and brewing up that rich taste of strong cowboy coffee are all part of Kent's school where cooks learn how to cook just as they did for the wranglers who herded cattle along the trail drives over 140 years ago. Kent's accomplishments for his culinary talent has earned him numerous awards, including the uncontested title as the Official Chuck Wagon Cook of Oklahoma, given to him by the Oklahoma state Governor. He also won the Chuck wagon Cook-Off Championship at the National Cowboy Symposium Celebration held in Lubbock, Texas and the Will Rogers Award for Chuck Wagon of the Year by the Academy of Western Artists. Featured on QVC, PBS, The Food Network's "Roker on the Road" and "Throw-Down with Bobby Flay." Kent entertains with a passion as both a modern day cowboy, story teller and one of the nations finest cooks. Recently, the Rollins offered a Contest for a scholarship to attend their cooking school. -

SPEC WLJ V84 N09.Pdf (5.043Mb)

The National Livestock Weekly December 13, 2004 • Vol. 84, No. 09 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication BSE trade rule moving ahead — Meat group denied mented, and we’re disappointed nal rule is published. In terms of timeliness, the court ulate a significant interest in the ‘intervener’ status. that those interests will not be im- NMA wanted to be kept abreast said, the only documents current- proceedings at this junction. NMA mediately represented before the of the rule changes and felt its ly being filed with them on this feels that once a final rule is issued A U.S. District Court in Mon- court.” membership needed similar notifi- matter is status reports and allow- by USDA, the court will hold a tana recently denied the National R-CALF filed the case in April cation. NMA said if R-CALF fol- ing intervention would likely prej- different opinion. Meat Association’s (NMA) request when USDA announced it was re- lows through with its intent to keep udice both R-CALF and USDA. On the last issue, Cebull held for intervener status in the Cana- opening the border to Canadian the border closed, NMAwould have Referencing related interest, the that USDA can defend the com- dian border reopening case involv- imports. R-CALF filed an injunc- immediate legal status in the court. court said, “While NMA may well pleteness of its procedures for de- ing R-CALF USA and USDA. The tion against the action saying it Both R-CALF and USDA op- have some cognizable interest in veloping a new rule, and, even if court did leave the option open for would jeopardize the health and posed NMA’s motion. -

IGRA) Pre-Export Test for Rodeo Cattle of the Breeds Corriente, Brahman Texas Longhorns, and American Bucking Bulls (ABBI)* Guidance for Accredited Veterinarians

Obtaining an Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) Pre-Export Test for Rodeo Cattle of the breeds Corriente, Brahman Texas Longhorns, and American Bucking Bulls (ABBI)* Guidance For Accredited Veterinarians For exportations of U.S. cattle of the breeds Corriente, Brahman, Texas Longhorn, and American Bucking Bull (ABBI)* to Canada on the Cattle for Breeding to Canada certificate for any purpose, an Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) test is required for pre-export testing for bovine tuberculosis (M. Bovis), in addition to the caudal fold test. This requirement is as follows: Rodeo or roping type cattle limited to the breeds Corriente, Brahman, Texas Longhorns, and American Bucking Bull (ABBI)* (other than those temporarily imported under 90 days for exhibition) are also required to be tested negative by the Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) test in addition to the caudal fold test, regardless of end-use in Canada. The blood sample must be drawn between 72 hours and 30 days following the caudal fold injection. *NOTE: If the animal is considered an “American Bucking Bull/ ABBI” animal, but is not of the breeds Corriente, Brahman, or Texas Longhorn, the importer may apply for a CFIA import permit, listing the accurate breed lineage of the animal other than American Bucking Bull/ ABBI, and the animal will not require an IGRA test. In these cases, the entry of “breed/category” on the corresponding export health certificate must match the CFIA import permit. All animals listed as “American Bucking Bull/ ABBI” on the CFIA import permit, or in the “breed/category” field of the export health certificate must have an IGRA test, regardless of true breed lineage. -

Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association 2018 Rule Book

Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association 2018 Rule Book Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association Articles of Incorporation, Bylaws and Rules REVISED Effective October 1, 2017 Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association 101 Pro Rodeo Drive • Colorado Springs, CO 80919 719.593.8840 Copyright © 2018 by the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association B1.2.4 Assumption of Risk and Release of Liability. THIS IS A RELEASE OF LIABILITY. BY BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE PRCA, YOU ARE AGREEING TO RELEASE THE PRCA AND OTHER PARTIES FROM LIABILITY. PLEASE READ THIS PROVISION CAREFULLY. Members acknowledge that rodeo events, including PRCA- sanc- tioned events, are inherently dangerous activities. Members further acknowledge that participation in a PRCA-sanctioned event (whether as a competitor, independent contractor, official, laborer, volunteer or observer) exposes the participant to substantial and serious hazards and risks of property damage, personal injury and/or death. Each Member, in consideration of his membership in the PRCA and his being permitted to participate in a PRCA-sanctioned event in any capacity, does by such membership and participation agree to assume such hazards and risks. Each Member further agrees to discharge, waive, release and covenant not to sue PRCA, PRCA Properties (“PRCAP”), all PRCA sponsors, all Members (including, without limitation, contestants, Stock Contractors, Rodeo Committees, Rodeo Producers and Contract Personnel), and any other PRCA-sanctioned event production entity (and each party’s respective officers, directors, employees and agents), from all claims, demands and liabilities for any and all property damage, personal injury and/or death arising from such Member’s participation in a PRCA- sanctioned event. This discharge, waiver and release includes claims, demands and liabilities that are known or unknown, foreseen or unfore- seen, future or contingent, and includes claims, demands, and liabilities arising out of the negligence of the parties so released by such Member. -

Lawsuit Threatens Planned Horse Gather

The National Livestock Weekly November 30, 2009 • Vol. 89, No. 08 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” Web site: www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication INSIDE WLJ Lawsuit threatens planned horse gather TTCFACFA CONFERENCE—TheCONFERENCE Texas Cattle Feeders Association (TCFA) A lawsuit filed last week in the Associated Press last week much in conformance” with the populations in the wild, but also annual meeting last week focused Washington, D.C., Federal District that the lawsuit is “not unexpect- act, which he said requires BLM maintaining federal facilities on the challenges facing the sector. Court may block the planned gath- ed” given the “climate of the whole to manage the herds to appropri- meant to hold horses across the Monte Cluck, TCFA chairman, er of 2,700 wild horses north of wild horse world right now.” ate population levels. “We need to West. The program has been in praised cattle feeders for their per- Reno, NV, next month. The suit, “It is a pretty big management remove some excess animals here. crisis as costs continue to rise, with severance in the face of adversity and reminded the group that they filed by California-based In De- action we need to take in this ar- It just happens to be a lot of excess few viable long-term options avail- have faced tough times in the past fense of Animals (IDA), claims that ea,” he said of the agency’s plans animals,” Shepherd said. able to the agency. BLM has been and survived. -

A Guide to Veterinary Service at PRCA Rodeos

A Guide to Veterinary Service at PRCA Rodeos A publication of the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association 2 A Guide to Veterinary Service at PRCA Rodeos A publication of the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association Revised edition published October 2015 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 THE VETERINARIAN’S ROLE AT PRCA RODEOS........................................................... 4 PLANNING FOR THE RODEO............................................................................................... 5 SAMPLE PROCEDURE FOR INJURED ANIMALS............................................................ 7 SAMPLE LIVESTOCK WELFARE STATEMENT.............................................................. 8 SUGGESTED EQUIPMENT AND MEDICATIONS.............................................................. 9 DURING THE RODEO............................................................................................................. 10 HANDLING INJURIES IN THE ARENA ………………………………………..…............ 10 LIVESTOCK AMBULANCE OR REMOVAL SYSTEM....................................................... 12 EUTHANASIA............................................................................................................................ 14 INSURANCE................................................................................................................................. 15 A FINAL WORD......................................................................................................................... -

Angus Bull Sale

LIVESTOCK ROUNDUP Midwest Messenger | January 11, 2019 | Page 17 African swine fever: China struggle continues As of early 2019, China has reported more than 100 cases of African swine fever (ASF) in 19 provinces and four municipalities, including Beijing, for a total of 23 distinct geographic areas. Recent outbreaks have been reported in Guangdong and Fujian provinces. However, a new case in the north’s Heilongjiang province has aff ected a farm with 73,000 pigs, the largest farm yet to report a case of the deadly disease. On Dec. 25, Chinese offi cials announced the detection of ASF virus in some protein powders made using pork blood manufactured by a Tianjin-based company. The raw materials for the batches were from 12 slaughter and processing plants in Tianjin. The new ASF case occurred despite the farm banning of the use of food waste and pig blood as raw materials in the production of feed for pigs, in a bid to halt the spread of the disease. In a related move, China recently announced that slaughterhouses will need to run a test for ASF virus on pig products before selling them. Slaughterhouses must slaughter the pigs from diff erent origins separately. They can only sell the products if blood of the same batch of pigs is tested negative for African swine fever virus. If an ASF outbreak is found, slaughterhouses must cull all pigs Looking William Kruse Sr. of Winnetoon, Neb., with his black Poland to be slaughtered and suspend operations for at least 48 hours, China hogs in the 1940s. -

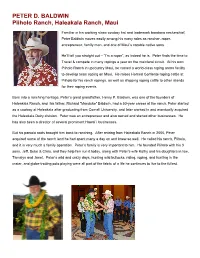

PETER D. BALDWIN Piiholo Ranch, Haleakala Ranch, Maui

PETER D. BALDWIN Piiholo Ranch, Haleakala Ranch, Maui Familiar in his working straw cowboy hat and trademark bandana neckerchief, Peter Baldwin moves easily among his many roles as rancher, roper, entrepreneur, family man, and one of Maui’s notable native sons. He’ll tell you straight out – “I’m a roper”, as indeed he is. Peter finds the time to Travel & compete in many ropings a year on the mainland circuit. At his own Piiholo Ranch in upcountry Maui, he carved a world-class roping arena facility to develop team roping on Maui. He raises Horned Corriente roping cattle at Piiholo for his ranch ropings, as well as shipping roping cattle to other islands for their roping events. Born into a ranching heritage, Peter’s great grandfather, Henry P. Baldwin, was one of the founders of Haleakala Ranch, and his father, Richard “Manduke” Baldwin, had a 50-year career at the ranch. Peter started as a cowboy at Haleakala after graduating from Cornell University, and later worked in and eventually acquired the Haleakala Dairy division. Peter was an entrepreneur and also owned and started other businesses. He has also been a director of several prominent Hawai`i businesses. But his paniolo roots brought him back to ranching. After retiring from Haleakala Ranch in 2000, Peter acquired some of the ranch land he had spent many a day on and knew so well. He called his ranch, Piiholo, and it is very much a family operation. Peter’s family is very important to him. He founded Piiholo with his 3 sons, Jeff, Duke & Chris, and they help him run it today, along with Peter’s wife Kathy and his daughters in law, Tamalyn and Janet. -

NACA Judging Guidelines

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced in whole, or in part, in any form or by any means, without prior express permission from the North American Corriente Association. Judging Guidelines for Corriente Cattle Judging Guidelines for Corriente Cattle Revised February 6, 1996; March, 1998; March, 2000; May, 2004; January, 2005; January, 2006 May, 2010; Feb, 2014 Aug 2014 These guidelines are intended to be used as guidelines only, not rules for which there are no exceptions. If you have comments, suggestions, or questions about any part of them, please do not hesitate to let the NACA know. From time to time, the Board of Directors will review these guidelines, and will take into consideration any information received from our members. A judge of Corriente cattle should evaluate them as an animal bred specifically for excellent performance in the rodeo arena. Many typical characteristics of the beef breeds are not desirable, nor are the excessively long horns of the Texas Longhorn or the Watusi. Corrientes are not beefy, heavily muscled, tall or rawboned. They are small, trim cattle with sufficient bone and strength for easy action and endurance. Regardless of use, the general conformation, horn shape, and disposition remain the same. It is important for a judge to keep in mind the birth date of each animal in a class. For example, a class for yearling bulls will often require the judge to be able to compare the qualities of a 6- month old animal against those of a 12-month old, and allow for considerable differences in size and horn growth. -

The Cowboy Lawyer

OKLAHOMA FARM & RANCH FebruaryOKFR 2020 | www.okfronline.com | Volume 5 Issue 2 The Cowboy Lawyer Brad West FREE 2 | FEBRUARY 2020 OKFR WWW.OKFRONLINE.COM FEBRUARY 2020 | 3 4 | FEBRUARY 2020 OKFR OklahOMA Farm & RANCH OKFR letter from the editor publishing contribution PUBLISHER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS JM Winter Andy Anderson Will Chaney EDITOR Tony Dean Savannah Magoteaux Ddee Haynes [email protected] Phillip Kitts Summer McMillen Garrett Metcalf, DVM Happy Valentines production Lacey Newlin D a y t o a l l o f Bryan Painter ART DIRECTOR Rayford Pullen Kayla Jean Woolf our wonderful Pat Reeder [email protected] Hreaders. Janice Russell Beth Watkins Thank you for picking advertising executives Barry Whitworth up this February edition Rosemary Stephens of Oklahoma Farm & COPY EDITORS [email protected] Judy Wade Ranch. Krista Lucas Kathy Miller This is the month [email protected] of love, and we see it distribution everywhere. Bouquets Sherrie Nelson MANAGER [email protected] Pamela Black of roses, hearts, chocolates - they’re all symbols of love and [email protected] affection. administration DISTRIBUTORS Still, we farmers, ranchers, cowboys and cowgirls show love Pamala Black every day. We show it to the animals we care for, and the land we Brenda Bingham Pat Blackburn [email protected] Tina Geurin are stewards of. Yes, we make our living on the land and with our herds, but you can’t convince me that most of us don’t love our land and animals. CONTACT US Out amongst the horses and cattle, I am once again in awe of what Oklahoma Farm & Ranch magazine our God has created. -

Chapter 8 Horse (Equine) and Livestock Guidelines

Guidelines for the Safe Use of Animals in Filmed Media CHAPTER 8 HORSE (EQUINE) AND LIVESTOCK GUIDELINES The horse is one of the most commonly used animals in filmmaking and, for that reason, we generally use the term “horse” in the following sections These Guidelines pertain to all equines ADVISORY: American Humane Association’s Guidelines for the Safe Use of Animals in Filmed Media apply to all horses and livestock without regard to their prominence or insignificance to the production This includes anyone bringing an animal to the set, including privately owned animals furnished to the production by historic re-enactors, other private suppliers, stunt personnel, directors, or any other members of the cast or crew For safety and efficiency, American Humane Association recommends that producers hire animal handlers experienced in motion picture production to supply all horses and livestock for production However, if production chooses to have private owners (including cast and crew) provide horses and livestock, all requirements of the Guidelines must be implemented When applicable, producers shall distribute in advance the instruction sheet on “Special Requirements for Extras/Others Who Supply Animals ” In productions involving large numbers of animals (e g , historic reenactments), a responsible “chain of command” shall be established to coordinate the work during production The chain-of-command information shall be provided to American Humane Association The designated “commander” of each unit will be directly responsible for the conduct of the people and the care of the animals under his/her supervision ADVISORY: American Humane Association discourages the use of Mexican fighting bulls for filming, due to their unpredictable temperament Contact American Humane Association for prior approval in using Mexican fighting Bulls Because of their unpredictable temperament, innate aggression and heightened reaction to movement, additional safety precautions should be in place * Notes a federal, state or local animal welfare statute, code or permit consideration.