Youth Justice at the Interface: the Development of a Multi-Professional Team in a Multi-Agency Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival Films BUSINESS SCHOOL

Uniview Vol. 28 No. 1, Summer 2009 Festival Films BUSINESS SCHOOL Join our Corporate Circle Program and keep in the loop. James Mactier Tracey Horton Jimmy Wilson Sunny Takashi Susan Oldmeadow-Hall Chris Ryder B Agr Ec (Hons), B Ec (Hons) UWA BSc Natal Uni, South Africa B Int Law, Waseda Uni, Japan B Com (UWA) LLB (Hons), Victoria Uni, NZ University of Sydney MBA Stanford University President: BHP Billiton General Manager: Partner: Ernst & Young MBA, Trinity College, Dublin Executive Director: Dean: UWA Business School Stainless Steel Materials Mitsui & Co. (Australia) Ltd Assurance and Advisory Partner-In-Charge, Perth Offi ce: Macquarie Bank Limited Chair: D’Orsogna Board Member: Perth Offi ce, Business Services, Corrs Chambers Westgarth Trustee: UWA Business School Chairman: Japanese Association Associate Member: Institute Admitted: Barrister & Solicitor Western Australian Museum of Western Australia. of Chartered Accounts, in New Zealand and Governor: Western Australian Fellow: Australian Institute of Western Australia Museum Foundation Company Directors (AICD), Financial Member: Construction BC&YUNBS107 Member: Services Institute of Australasia, Committee of Law Council Edge Employment Board Member: AICD’s National of Australia Financial Reporting Committee, Ernst & Young’s Global IFRS Extractive Industries Group, and Women’s Leadership Group. Looking to develop an ongoing and supportive relationship with The University of Western Australia’s Business School, the broader business community, and like-minded Business Professionals? The Business School Corporate Circle Program is a membership-style program providing companies with information, networking, training, hospitality and acknowledgement benefi ts. Membership categories include Silver ($10,000) and Gold ($20,000). For further information, please contact Kylie Aitkenhead on (08) 6488 8538. -

Annual Report

Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation and Analysis Annual Report CMCA | 2014–2015 01 14 From the Director User Profile 02 16 Affliations Centre Highlights 04 23 Techniques Conferences and Visits 06 26 Feature Story Grant Success 07 29 Research Highlights Journal Papers 13 50 Impacting on Industry Journal Covers Inside Cover Image: Growing protein crystals, acquired by Paul Rigby on an Olympus BH-2 microscope, captured using polarised light Cover Image: Tight junction degradation of asthmatic airway epithelium in response to Human Rhinovirus exposure, acquired on the Nikon A1 confocal by Alysia Buckley, CMCA@Perkins From the Director The CMCA User Pathway is the concept- Multi-modal imaging is just one to-publication sequence of activities example of advanced data challenges that drives all aspects of what we that CMCA is seeking to meet head on do – ideate – register – plan – train with new academic lead, Dr Andrew – collect – analyse – publish. From Mehnert, who is designing strategies brainstorming and sanity checking at to support users at all levels, and the start, to providing blueprints for engaging with Australia’s eResearch methods sections and editing papers and informatics community, both Image: CMCA Director – at the finish, CMCA’s goal is to provide within the National Imaging Facility Professor David Sampson complete research solutions – and (NIF), the Australian Microscopy As we go to press in 2016, the NCRIS increasingly these solutions involve and Microanalysis Research Facility roadmapping process is well underway. multiple instrument platforms, and (AMMRF), and without. Undoubtedly, As a node of three capabilities, doing more with the data. more resources are needed in this area, AMMRF, MA and NIF, and partner in and we are looking for ways to achieve two more, the Australian National Correlative multi-modal microscopy this. -

A Tribute to Professor Ian Smith an Haldane Smith, Former Professor of Palmes Académiques

Celebrate! Graduate Award winners, Elizabeth Thomas and Timothy McCormack, with Chancellor, Dr Mike Vertigan, Mrs Jo Le Grew and Vice-Chancellor, Professor Daryl Le Grew elebrate’ was the theme of the 2003 University of Chemical Weapons Convention and the International Criminal ‘CTasmania fifth annual Foundation Dinner. And what a Court. celebration it was. “Without his expertise in championing the cause, many believe Two outstanding graduates were recognised and 118 Tasmania the Government would not have ratified the treaty establishing Scholarship and Bursary winners were showcased before more the International Criminal Court,” Vice-Chancellor Daryl than 420 guests from business, government and academic Le Grew said. spheres. Appointed Amicus Curiae, or friend of the court, Professor The post university achievements of former Public Trustee chief McCormack flew to The Hague the day after the celebrations to executive Elizabeth Thomas and Foundation Australian Red give advice on matters of international law to judges presiding Cross Professor of International Humanitarian Law at the over the trial of former Yugoslavian leader Slobodan Milosevic. University of Melbourne, Timothy McCormack were recognised “It’s a big opportunity for a young Burnie boy,” Professor with Foundation Graduate Awards. McCormack said. Professor McCormack has been lauded for his work, both in He classes his wife as his greatest benefit from university, and theory and practice, in International Humanitarian Law and credits one of his lecturers as the person who inspired his credited with swaying the Australian Government on the interest in international humanitarian law, which he believes can “make the world a better place”. Professor McCormack said North West educated kids can and do “make good”. -

Politics, Power and Protest in the Vietnam War Era

Chapter 6 POLITICS, POWER AND PROTEST IN THE VIETNAM WAR ERA In 1962 the Australian government, led by Sir Robert Menzies, sent a group of 30 military advisers to Vietnam. The decision to become Photograph showing an anti-war rally during the 1960s. involved in a con¯ict in Vietnam began one of Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War led to the largest the most controversial eras in Australia's protest movement we had ever experienced. history. It came at a time when the world was divided between nations that were INQUIRY communist and those that were not; when · How did the Australian government respond to the communism was believed to be a real threat to threat of communism after World War II? capitalist societies such as the United States · Why did Australia become involved in the Vietnam War? and Australia. · How did various groups respond to Australia's The Menzies government put great effort into involvement in the Vietnam War? linking Australia to United States foreign · What was the impact of the war on Australia and/ policy in the Asia-Paci®c region. With the or neighbouring countries? communist revolution in China in 1949, the invasion of South Korea by communist North A student: Korea in 1950, and the con¯ict in Vietnam, 5.1 explains social, political and cultural Australia looked increasingly to the United developments and events and evaluates their States to contain communism in this part of the impact on Australian life world. The war in Vietnam engulfed the 5.2 assesses the impact of international events and relationships on Australia's history Indochinese region and mobilised hundreds of 5.3 explains the changing rights and freedoms of thousands of people in a global protest against Aboriginal peoples and other groups in Australia the horror of war. -

Child Trafficking and Care Provision

1 Paul Rigby is a registered social worker who has worked for nearly twenty years in front line practice, management policy development and research in the field of youth and criminal justice social work in Scotland. He has worked in Glasgow City Council’s child protection team for five years and is also seconded part time to the Development Centre for Scotland at the University of Edinburgh. In Glasgow, Paul has been involved in child trafficking research, policy and practice development design and implementing a number of projects that have informed local and national responses. He has published a number of research reports and papers that address the question of prevalence, and challenges for child protection professionals in addressing child trafficking. Margaret Malloch is a Senior Research Fellow with the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at the University of Stirling. She has conducted extensive research in the field of youth justice, particularly in relation to criminal and social justice responses to children in conflict with the law. She has conducted evaluations of voluntary and statutory responses to young people who have run away from home and local authority accommodation in Scotland. Recent work has included a review of models of care and support for adult victims of human trafficking in Scotland. Niall Hamilton-Smith is a criminologist at Stirling University, a member of the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research, and a former member of the Organised Crime research team at the Home Office. Whilst, at the Home Office, he had responsibility for research into organised immigration crime and as such has worked on a variety of projects relating to development of the evidence base on Human Trafficking, including the provision of appropriate services to victims. -

Planned for Progress

Planned for Progress 65 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 | GPO Box 3947, Sydney NSW 2001 Modernism and Dr Coombs In 1952 the Governor of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Dr H. C. Coombs (1906-1997), commissioned a painting of Australian wildflowers from the artist, Margaret Preston. He specified that the picture should include native flowers of Western Australia, and when they began to bloom in the west, specimens were transported by airfreight to the artist’s house in Sydney’s Mosman. Preston combined them with local varieties to create an exuberant, detailed painting. The unlikely companionship of native flora from different states appealed to Coombs, perhaps prompting memories of his earlier life in Western Australia, mixed with current experiences in New South Wales. His mind also made companions of various interests throughout his career: economics, education, art, design, indigenous culture and politics. Margaret Preston’s painting was reproduced on the Bank’s Christmas card for that year, and the work was acquired for its art collection. The choice of Preston’s wildflowers for a Christmas card now seems pleasing, but in the 1950s conventional images from the northern hemisphere were more customary, and anaemic reproductions of European art were the preference for office walls. Dr Coombs found tiresome the entire enterprise of Christmas cards, so he converted it to a means of supporting contemporary artists and developing an art collection for the Bank. Margaret Preston (Australia 1875-1963), Australian wildflowers, 1952, oil on canvas, 43 x 48 cm. Cover image: Perspective of the Bonds and Stock banking chamber, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, c.1964, watercolour and ink, 55 x 43 cm. -

THE ADELAIDE DENTAL SCHOOL 1917 to 2017 Share This Book

THE ADELAIDE DENTAL SCHOOL 1917 TO 2017 Share this book Thehigh-quality paperback edition of this book is available for purchase from www.adelaide.edu. au/press Suggestedcitation: Rogers, J, Townsend, G and Brown, T (2018). 1heAdelaide Dental School 1917 to 2017. Adelaide: Barr Smith Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20851/dental-histor y License: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 The Adelaide Dental School 1917 to 2017 by James Rogers Grant Townsend Tasman Brown Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press Barr Smith Library The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The Barr Smith Press is an imprint of the University of Adelaide Press, under which titles about the history of the University are published. The University of Adelaide Press publishes peer-reviewed scholarly books. It aims to maximise access to the best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high-quality printed volumes. This book is typeset in Helvetica Neue and Adobe Garamond Pro and uses minimal capitalisation, reflecting the preferred style of the University of Adelaide Press and its imprint, the Barr Smith Press. © 2018 James Rogers, Grant Townsend and Tasman Brown This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. -

Western Australia to Communicate with South Africa, Java, Holland, England, and America

W.A. A.M. Radio Stations. Part of the most comprehensive list ever compiled of Australian A.M. broadcasting stations. 6AG Perth 1923. Broadcast station owned by Walter Coxon. Transmitter at Highgate. Originally licensed as Morse code station XYK at Darlington. Walter was the first person in Western Australia to communicate with South Africa, Java, Holland, England, and America. In October 1918 Walter was the first in Australia to demonstrate music and speech broadcasts, from one side of the Perth Agricultural Show to the other. He often broadcast concerts from his lounge room. Appointed President of the Wireless Institute of Australia (W.A. Division). He was the first person in Australia to use a water-cooled transmitter valve, and was described as “The Father of Radio in Western Australia”. He was the first Chief Engineer of 6WF, and later designed and equipped commercial stations 6ML, 6BY, and 6AM. Walter also pioneered the technical work for the Royal Flying Doctor Radio Service throughout Western Australia. 6AB Kalgoorlie 1923. Broadcast station owned by Clyde Cecil who was the grandfather of John Cecil; current manager (2007) of 6AL. Clyde was a School of Mines teacher, and built the first aeroplane in Kalgoorlie. 6BN Perth 05-12-1923. Broadcast station owned by A. Stevens with weekly broadcasts until 6WF opened. Transmitter at South Perth. Heard over 600 kilometres away while using only one watt. 6AM Perth. Broadcast station owned by Peter Kennedy. Transmitter at Mt Lawley. He relayed a message to King George V from the Wireless Institute of Australia on 7-8-1925. -

1 Lucien Leon December 2013 on the Use of the Digital Moving Image In

Lucien Leon December 2013 On the use of the digital moving image in retooling the Australian political cartooning tradition to a new media context. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The Australian National University 1 DECLARATION BY CANDIDATE I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been acknowledged. Signature: ……………………………………………… Date: ……………19 December 2013…………………. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title page 1 Declaration by Candidate 2 Acknowledgements 4 Dedication 5 List of Illustrations 6 List of Author’s Moving Image Works 9 Abstract 11 Introduction 13 Chapter 1: Part 1 - Historical Context 19 Chapter 1: Part 2 - The Beginnings of a Moving Image Tradition 32 Chapter 2: Visual Satire and Australian Society 51 Chapter 3: Part 1 – On Moving Image as Political Cartoon 70 Chapter 3: Part 2 – The Video Mash-up Image 114 Chapter 4: A Revised Taxonomy for the Categorisation of Political Cartoon Images 133 Chapter 5: Developing a Political Animation Practice 169 Chapter 6: Political Satire in the New Media Age 205 Conclusion 225 Bibliography 232 Appendix 1 List of publications and presentations 241 Appendix 2 List of creative practice 242 Appendix 3 List of author’s moving image works and synopses 244 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It has been my pleasure to enjoy the support of so erudite and engaging a supervisory chair as Professor Paul Pickering, Director of the Research School of Humanities and the Arts. He helped me to coax and cajole the disparate threads running through my thesis into a genuinely interdisciplinary project. -

Youngbook-Pgs 601-700.Pdf

The YOUNG Families of Early Giles Co TN 601 Orvis F Moore [Y1d1f2], son of Clementine Richard Moore [Y3a7h7], son of John Alford Virginia Young and George W Moore, was born 14 Moore and Callie Otelia Richards, was born 21 September 1910 in Bedford Co TN, and died in Sep- November 1913 in Red River Co TX, and died 10 tember 1982 at Shelbyville. He married Donnie January 1989 at New Braunfels, Comal Co. He mar- Roberts in Bedford Co on 18 November 1933; both ried Neacy Ruth Moore, at Ropesville, Hockley Co were from Petersburg when they married, but were TX on 12 September 1935. She was born in 1919 in next door neighbors in 1930 in Lincoln Co. She was TX. They lived at Lubbock in the 1980s and had a widow in 1930. She was age 31 when married, three children- born 20 June 1902 in Lincoln Co, daughter of James a. Merlin Richard Moore, b 26 Sep 1936 Rutledge Roberts (1869 TN) and Mary Bell Muse b. Sylvia Donetta Moore, b 10 Dec 1938 (1875 TN). Dennis Roberts verified her birth date c. Darwin Lee Moore, b 6 Oct 1953 (DL,89b, for the marriage. W T Sorrels helped with the mar- 111bmP) riage bond. "Mrs Orvis Moore," age 34, died 18 September 1936 at Petersburg, and was buried there. Robert Lee Moore [Y3a7e5a], son of Hubert Her home was at Shelbyville in Bedford Co when Roland Moore and Ella Sutton Joyner, was born 28 she died. They had a son- November 1927 in Red River Co TX. -

Doughty2020.Pdf (5.822Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Representations of the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’ within the British media, 1973- 1997. Roseanna Doughty. PhD in History. The University of Edinburgh. 2019. ii iii Declaration of own work: I declare that the following thesis has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgement, the work presented is entirely my own. Roseanna Doughty October 2019 iv v Abstract. This thesis investigates British media representations of the conflict in Northern Ireland between 1973 and 1997, and how these affected the lived experiences of the Irish in Britain over this period. The ‘Troubles’ dominated headlines from the outbreak of communal violence in 1968. As the main source of information on Northern Ireland for most British people, the press and broadcast media were central to how the conflict was reported on and understood in Britain. -

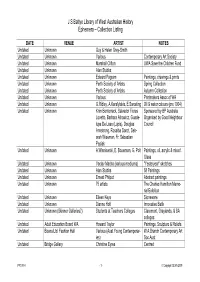

JS Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing DATE VENUE ARTIST NOTES Undated Unknown Guy & Helen Grey-Smith Undated Unknown Various Contemporary Art Society Undated Unknown Marshall Clifton UWA Save the Children Fund Undated Unknown Alan Stubbs Undated Unknown Edward Pagram Paintings, drawings & prints Undated Unknown Perth Society of Artists Spring Collection Undated Unknown Perth Society of Artists Autumn Collection Undated Unknown Various Printmakers Assoc of WA Undated Unknown G.Ridley, A.Karafylakis, E.Sweeting Oil & water colours (pre 1964) Undated Unknown Krim Benterrack, Salvador Flores Sponsored by BP Australia Lovetto, Barbara Albowicz, Guade- Organised by Good Neighbour lupe De Laso (Lupis), Douglas Council Armstrong, Rosalba Danzi, Deb- orah Wiseman, Fr. Sebastian Pepiak Undated Unknown A.Wisniewski, E. Bouwman, G. Polt Paintings, oil, acrylic & mixed. Glass Undated Unknown Vaclav Macha (various mediums) "Yesteryear" sketches Undated Unknown Alan Stubbs 58 Paintings Undated Unknown Ernest Philpot Abstract paintings Undated Unknown 75 artists The Charles Hamilton Memo- rial Exibition Undated Unknown Eileen Keys Stoneware Undated Unknown Dianne Hoft Innovative Batik Undated Unknown (Skinner Galleries?) Students at Teachers Colleges Claremont, Graylands, & SA colleges Undated Adult Education Board WA Howard Taylor Paintings, Sculpture & Reliefs Undated Boans Ltd. Fashion Hall Various (Aust.Young Contemporar- W.A.Branch Contemporary Art ies) Soc Aust Undated Bridge Gallery Christine Eyres Centred PR10914 - 1 - © Copyright SLWA 2009 J S Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing DATE VENUE ARTIST NOTES Undated Bridgetown Repertory Hall Leith Angelo Undated Cottesloe Civic Centre Tam Abrose 41 Paintings of WA Undated Claremont School of Art Annie Q Medley Iconoclasm and Still Life Undated Claude Hotchin Gallery - Boans Various W.A.Branch Contemporary Art Soc.