1 Listening for Tertiary Rhetoric in Haydn's Op. 77 String Quartets by Floyd Grave Abstract in a Pair of Recent Essays, Elaine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

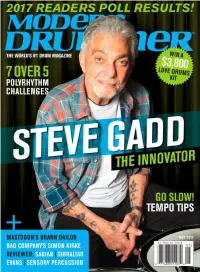

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 9 Number 1 Spring 2019 Article 2 March 2019 Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets Matthew J. Hall Cornell University Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Hall, Matthew J. (2019) "Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 9 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Hall, Matthew. “Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 9.1 (Spring 2019), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2019. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets By Matthew J. Hall Cornell University Abstract The predominance of major-mode works in the repertoire corresponds with the view that minor-mode works are exceptions to a major-mode norm. For example, Charles Rosen’s Sonata Forms, James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s Sonata Theory, and William Caplin’s Classical Form all theorize from the perspective of a major-mode default. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, August 4th, 2012, 5:00-6:00 p.m. Claude Debussy (1862-1918). Danse (Tarantelle styrienne) (1891, 1903). David Allen Wehr, piano. Connoiseur Soc 4219, Tr 4, 5:21 Debussy. Danse, orch. Ravel (1923). Philharmonia Orchestra, Geoffrey Simon. Cala 1024, Tr 9, 5:01 Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Shéhérazade (1903). Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano, Cleveland Orchestra, Pierre Boulez. DG 2121, Tr 1-3, 17:16 Ravel. Introduction and Allegro (1905). Rachel Masters, harp, Christopher King, clarinet, Ulster Orchestra, Yan Pascal Tortelier. Chandos 8972, Tr 7, 11:12 Debussy. Sarabande, from Pour le piano (1901). Larissa Dedova, piano. Centaur 3094, Disk 4, Tr 6, 4:21 Debussy. Sarabande, orch. Ravel (1923). Ulster Orchestra, Yan Pascal Tortelier. Chandos 9129, Tr 2, 4:29 This time, he’d show them. The Paris Conservatoire accepted Ravel as a piano student at age 16, and even though he won a piano competition, more than anything he wanted to compose. But the Conservatory was a hard place. He never won the fugue prize, never won the composition prize, never won anything for writing music and they sent him packing. Twice. He studied with the great Gabriel Fauré, in school and out, but he just couldn’t make any headway with the ruling musical authorities. If it wasn’t clunky parallelisms in his counterpoint, it was unresolved chords in his harmony, but whatever the reason, four times he tried for the ultimate prize in composition, the Prix de Rome, and four times he was refused. -

Ludwig Van BEETHOVEN

BEETHOVEN Piano Pieces and Fragments Sergio Gallo, Piano Ludwig van BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) EN Piano Pieces and Fragments 1 ^ 13 Variations in A major on the Arietta ‘Es war einmal ein alter Mann’ Sketch in A major, Hess 60 (transcribed by A. Schmitz) (1818)* 0:31 & (‘Once Upon a Time there was an Old Man’) from Dittersdorf’s Theme with Variations in A major, Hess 72 (fragment) (1803) 2:42 Das rothe Käppchen (‘Red Riding Hood’), WoO 66 (1792) 13:10 * 2 Liedthema in G major, WoO 200, Hess 75 ‘O Hoffnung’ (1818) 0:22 Pastorella in C major, Bia. 622 (transcribed by F. Rovelli, b. 1979) (1815)* 0:23 ( Presto in G major, Bia. 277 (transcribed by A. Schmitz) (1793) 0:34 Ein Skizzenbuch aus den Jahren 1815 bis 1816 (Scheide-Skizzenbuch). Faksimile, Übertragung und Kommentar ) herausgegeben von Federica Rovelli gestützt auf Vorarbeiten von Dagmar von Busch-Weise, Bd. I: Faksimile, 4 Bagatelles, WoO 213: No. 2 in G major (transcribed by A. Schmitz) (1793) 0:29 ¡ Bd. II: Transkription, Bd. III: Kommentar, Verlag Beethoven-Haus (Beethoven, Skizzen und Entwürfe), Bonn. Piano Étude in B flat major, Hess 58 (c. 1800) 0:41 ™ 12 Piano Miniatures from the Sketchbooks (ed. J. van der Zanden, b. 1954) Piano Étude in C major, Hess 59 (c. 1800) 0:25 £ (Raptus Editions) (excerpts) (date unknown) 4:27 3 String Quintet in C major, WoO 62, Hess 41 No. 3. Klavierstück: Alla marcia in C major [Kafka Miscellany, f. 119v, 2–5] 0:25 4 I. Andante maestoso, ‘Letzter musikalischer Gedanke’ (‘Last musical idea’) No. -

Brentano String Quartet

“Passionate, uninhibited, and spellbinding” —London Independent Brentano String Quartet Saturday, October 17, 2015 Riverside Recital Hall Hancher University of Iowa A collaboration with the University of Iowa String Quartet Residency Program with further support from the Ida Cordelia Beam Distinguished Visiting Professor Program. THE PROGRAM BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Mark Steinberg violin Serena Canin violin Misha Amory viola Nina Lee cello Selections from The Art of the Fugue Johann Sebastian Bach Quartet No. 3, Op. 94 Benjamin Britten Duets: With moderate movement Ostinato: Very fast Solo: Very calm Burlesque: Fast - con fuoco Recitative and Passacaglia (La Serenissima): Slow Intermission Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 67 Johannes Brahms Vivace Andante Agitato (Allegretto non troppo) Poco Allegretto con variazioni The Brentano String Quartet appears by arrangement with David Rowe Artists www.davidroweartists.com. The Brentano String Quartet record for AEON (distributed by Allegro Media Group). www.brentanoquartet.com 2 THE ARTISTS Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. “Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding,” raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its “luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism.” In 2014, the Brentano Quartet succeeded the Tokyo Quartet as Artists in Residence at Yale University, departing from their fourteen-year residency at Princeton University. The quartet also currently serves as the collaborative ensemble for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The quartet has performed in the world’s most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. -

Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz

Classics & Jazz PAID Permit # 79 PRSRT STD PRSRT Late Fall 2020 U.S. Postage Aberdeen, SD Jazz New Naxos Bundle Deal Releases 3 for $30 see page 54 beginning on page 10 more @ more @ HBDirect.com HBDirect.com see page 22 OJC Bundle Deal P.O. Box 309 P.O. 05677 VT Center, Waterbury Address Service Requested 3 for $30 see page 48 Classical 50% Off beginning on page 24 more @ HBDirect.com 1/800/222-6872 www.hbdirect.com Classical New Releases beginning on page 28 more @ HBDirect.com Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Late Fall 2020 Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz Catalog, with a broad range of offers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Villa-Lobos: The Symphonies / Karabtchevsky; São Paulo SO [6 CDs] In jazz, we’re excited to present another major label as a Heitor Villa-Lobos has been described as ‘the single most significant 4 Classical - Boxed Sets 3 for $30 bundle deal – Original Jazz Classics – as well as a creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music.’ The eleven sale on Double Moon, recent Enlightenment boxed sets and 10 Classical - Naxos 3 for $30 Deal! symphonies - the enigmatic Symphony No. 5 has never been found new jazz releases. On the classical side, HBDirect is proud to 18 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray and may not ever have been written - range from the two earliest, be the industry leader when it comes to the comprehensive conceived in a broadly Central European tradition, to the final symphony 20 Classical - Recommendations presentation of new classical releases. -

Mark Evan Bonds

MARK EVAN BONDS Department of Music 1064 Sweetflag Lane University of North Carolina Hillsborough, NC 27278 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3320 [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS 1992- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Music, Cary C. Boshamer Distinguished Professor (2007- ); Professor (1997-2007); Associate Professor (1992-97) 1991 Harvard University, Department of Music, Visiting Assistant Professor (Fall Semester) 1988-92 Boston University, School of Music, Assistant Professor EDUCATION 1984-88 Harvard University, Ph.D. in Musicology (Dissertation: “Haydn’s False Recapitulations and the Perception of Sonata Form in the Eighteenth Century”) 1977-78 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, M.S. in Library Science 1975-77 Christian-Albrechts-Universität Kiel (W. Germany), M.A. in Musicology, with Distinction; Minor in German Literature (Thesis: “Das Cantus-firmus-Prinzip bei Haydn und Mozart”) 1971-75 Duke University, B.A. magna cum laude, with Distinction in Music PUBLICATIONS SCHOLARLY MONOGRAPHS Absolute Music: The History of an Idea. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. Paperback ed. 2017. Russian translation (Moscow: Delo) under contract for publication in early 2019. Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. Paperback ed. 2014. Spanish translation: Barcelona: Acantilado, 2014. Japanese translation: Tokyo: Artes, 2015. After Beethoven: Imperatives of Originality in the Symphony. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996. Reprint ed. 2013. Wordless Rhetoric: Musical Form and the Metaphor of the Oration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991. Reprint ed. 2013. Japanese translation: Tokyo: Ongaku No Tomo Sha, 2018. TEXTBOOKS Listen to This. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson, 2017. -

Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Comparative Analysis of Recorded Performances, Pp

BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mark Christopher Ferraguto August 2012 © 2012 Mark Christopher Ferraguto BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY Mark Christopher Ferraguto, PhD Cornell University 2012 Despite its established place in the orchestral repertory, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-flat, op. 60, has long challenged critics. Lacking titles and other extramusical signifiers, it posed a problem for nineteenth-century critics espousing programmatic modes of analysis; more recently, its aesthetic has been viewed as incongruent with that of the “heroic style,” the paradigm most strongly associated with Beethoven’s voice as a composer. Applying various methodologies, this study argues for a more complex view of the symphony’s aesthetic and cultural significance. Chapter I surveys the reception of the Fourth from its premiere to the present day, arguing that the symphony’s modern reputation emerged as a result of later nineteenth-century readings and misreadings. While the Fourth had a profound impact on Schumann, Berlioz, and Mendelssohn, it elicited more conflicted responses—including aporia and disavowal—from critics ranging from A. B. Marx to J. W. N. Sullivan and beyond. Recent scholarship on previously neglected works and genres has opened up new perspectives on Beethoven’s music, allowing for a fresh appreciation of the Fourth. Haydn’s legacy in 1805–6 provides the background for Chapter II, a study of Beethoven’s engagement with the Haydn–Mozart tradition. -

Piano: Resources

Resources AN ADDENDUM TO THE PIANO SYLLABUS 2015 EDITION Resources The following texts are useful for reference, teaching, and examination preparation. No single text is necessarily complete for examination purposes, but these recommended reading and resource lists provide valuable information to support teaching at all levels. Resources for Examination Preparation Repertoire Additional Syllabi of Celebration Series®, 2015 Edition: Piano Repertoire. The Royal Conservatory (Available online.) 12 vols. (Preparatory A–Level 10) with recordings. Associate Diploma (ARCT) in Piano Pedagogy Toronto, ON: The Frederick Harris Music Co., Licentiate Diploma (LRCM) in Piano Performance Limited, 2015. Popular Selection List (published biennially) Theory Syllabus Etudes Celebration Series®, 2015 Edition: Piano Etudes. 10 vols. Official Examination Papers (Levels 1–10) with recordings. Toronto, ON: The Royal Conservatory® Official Examination Papers. The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited, 2015. 15 vols. Toronto, ON: The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited, published annually. Technical Tests The Royal Conservatory of Music Piano Technique Book, Basic Rudiments 2008 Edition: “The Red Scale Book.” Toronto, ON: The Intermediate Rudiments Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited. Advanced Rudiments Scales, Chords, and Arpeggios for Piano: “The Brown Scale Introductory Harmony Book.” Toronto, ON: The Frederick Harris Music Co., Basic Harmony Limited, 2002. First published 1948. Basic Keyboard Harmony Technical Requirements for Piano, 2015 Edition. 9 vols. History 1: An Overview (Preparatory A–Level 8). Toronto, ON: The Frederick Intermediate Harmony Harris Music Co., Limited, 2015. Intermediate Keyboard Harmony History 2: Middle Ages to Classical Musicianship (Ear Tests and Sight Counterpoint Advanced Harmony Reading) Advanced Keyboard Harmony Berlin, Boris, and Andrew Markow. Four Star® Sight History 3: 19th Century to Present Reading and Ear Tests, 2015 Edition.