Final Nov-Dec 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divya Sandesha

DIVYA SANDESHA Pujya Shri Ramchandraji Maharaj’s (Shri Babuji) letters to Sri S.A.Sarnadji Divya Sandesh: A Collection of letters of Pujya Shri Ramchandraji Maharaj (Shri Babuji) of Shahjahanpur to Shri (Late) S.A.Sarnadji, edited by Smt. Shakuntala Bai Sarnad and published by Shree Prakashana, NGO Colony, Jewargi Road, Gulbarga. PUBLISHER’S NOTE After the demise of Sri S.A.Sarnadji, while searching the papers of old house at our village and other immoveable property, we could find a bunch of letters and few Sanskrit books kept safely. These letters are in Urdu, Hindi and English. We learnt that Urdu letters are written/got written by Pujya Babuji Maharaj to Sarnadji. The other letters are written by Sri Ishwar Sahaji, Sri Raghavendra Raoji and Dr. K.C Vardachariji. We were inspired by these letters and thought of publishing Pujya Babuji’s letters with translations so as abhyasi brothers and sisters would be benifited and they can see the original hand writings of a great special personality Pujya Babuji Maharaj. We felt irrelevent since these letters are written to Sarnadji in a personal capacity and not as an office bearer. Probably Sarnadji must have thought likewise and did not take any interst in this regard and moreover none of our family members was aware of these letters. Though these letters are personal, the need to publish the letters with translations was felt to enable the true seekers of spirituality to perceive the message of love, advice and guidance embodied therein lest these letters written in formative years of a Sadhaka with humility, compassion and concern by Pujaya Babuji Maharaj may be lost for ever. -

VIVEKANANDA and the ART of MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1

VIVEKANANDA AND THE ART OF MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1 1. Episodes from Vivekananda’s life 2. Episodes from Ramakrishna’s life 3. Their memory power compared by Swami Saradananda 4. Other srutidharas from the past 5. The ancient art of memory 6. The laws of memory 7. The role of memory in daily life Episodes from Vivekananda’s life The human problem is one of memory. We have forgotten our divine nature. All the great teachers of the past have declared that the revival of the memory of our divinity is the paramount goal. Memory is a faculty and as such, it is neither good nor bad. Every action that we do, every thought that we think, leaves an indelible trail of memory. Whether we remember or not, the contents are recorded and affect our daily life. Therefore, an awareness of this faculty and its method of operation is vital for healthy existence. Properly employed, it leads us to enlightenment; abused or misused, it can torment us. So we must learn to use it properly, to strengthen it for our own improvement. In studying the life of Vivekananda, we come across many phenomenal examples of his amazing faculty of memory. In ‘Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda,’ Haripada Mitra relates the following story: One day, in the course of a talk, Swamiji quoted verbatim some two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. I wondered at this, not understanding how a sanyasin could get by heart so much from a secular book. I thought that he must have read it quite a number of times before he took orders. -

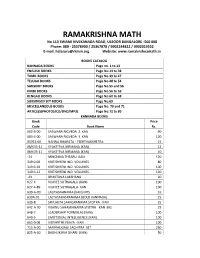

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

“ That This House, on the 150Th Birth Anniversary of Swami Vivekananda

The year 2013 is a very important year in the eventful calendar of the Ramakrishna Mission. This year happens to be the 150th Birthday Anniversary of Swami Vivekanada. Swamiji, as we call him, life’s mission was to propagate the teachings of the Vedanta, in the light of realisation of Sri Ramakrishna who is his master, throughout the world. “Swamiji has left behind a rich legacy for the future generations, in his writings on the four yogas, speeches, poetic compositions, epistles etc are in his book of complete works of Swami Vivekanda.” His birthday celebration has been celebrated throughout the world, of note in January 2013 UK Parliament recognised the valuable contribution made by Swamaji. The statement from the UK Parliament is: “ That this House, on the 150th Birth Anniversary of Swami Vivekananda, recognises the valuable contribution made by him to interfaith dialogue at international level, encouraging and promoting harmony and understanding between religions through his renowned lectures and presentations at the first World Parliament of the Religions in Chicago in 1893, followed by his lecture tours in the US and England and mainland Europe; notes that these rectified and improved the understanding of the Hindu faith outside India and dwelt upon universal goodness found within all religions; further notes that he inspired thousands to selflessly serve the distressed and those in need and promoted an egalitarian society free of all kinds of discrimination; and welcome the celebrations of his 150th Birth Anniversary in the UK and throughout the World” Vedanta Society, Brisbane Chapter celebrated the 150th Birthday Celebration and the 176th Birthday Celebration of Sri Ramakrishna on the 9th March 2013. -

Swami Chetanananda's Sunday Lectures from 1978 to 7/12/2020

Swami Chetanananda's Sunday lectures from 1978 to 7/12/2020 1 Self-Knowledge 1978/03/05 2 The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna 1978/03/12 3 Sri Ramakrishna and His Disciples 1978/03/19 4 Mystery of Resurrection 1978/03/26 5 Chaitanya: An Incarnation of Love 1978/04/02 6 The World We Live In 1978/04/09 7 Blessed are the Simple 1978/04/16 8 The Importance of Pilgrimage 1978/04/23 9 In the Company of the Holy 1978/04/30 10 Shankara and His Message 1978/05/07 11 Truth Alone Triumphs 1978/05/14 12 Buddha and His Message 1978/05/21 13 Devotion 1978/05/28 14 How to be Calm and Active 1978/06/04 15 The Beauty of Philosophy 1978/06/11 16 Four Gates of Liberation 1978/06/18 17 Is Life an Empty Dream? 1978/06/25 18 War and Peace in the Gita 1978/07/02 19 The Powers of the Mind 1978/07/09 20 Self-Surrender 1978/07/16 21 Tell Us the Way 1978/07/23 22 Krishna: The Shepherd Boy of Vrindavan 1978/07/30 23 Is Religion at Fault? 1978/09/03 24 Mystery of Love 1978/09/10 25 God Vision 1978/09/17 26 Human Destiny 1978/09/24 27 Blessed Are The Cheerful 1978/10/01 28 Mother Worship 1978/10/08 29 Dive Deep 1978/10/15 30 Man-making Religion 1978/10/22 vedantastl.org Last update 1/30/19 31 Who Is The Favorite of God? 1978/10/29 32 Religion and Miracles 1978/11/05 33 Kindle the Fire Within 1978/11/12 34 Why Do You Weep, My Friend? 1978/11/19 35 Mysticism 1978/11/26 36 Myth and Its Meaning 1978/12/03 37 They Lived With God - Swami Premananda 1978/12/05 38 They Lived With God - Swami Shivananda 1978/12/12 39 An Unseen Warfare 1978/12/10 40 Unceasing Prayer 1978/12/17 41 -

Om: One God Universal a Garland of Holy Offerings * * * * * * * * Viveka Leads to Ānanda

Om: One God Universal A Garland of Holy Offerings * * * * * * * * Viveka Leads To Ānanda VIVEKNANDA KENDRA PATRIKĀ Vol. 22 No. 2: AUGUST 1993 Represented By Murari and Sarla Nagar Truth is One God is Truth . God is One Om Shanti Mandiram Columbia MO 2001 The treasure was lost. We have regained it. This publication is not fully satisfactory. There is a tremendous scope for its improvement. Then why to publish it? The alternative was to let it get recycled. There is a popular saying in American academic circles: Publish or Perish. The only justification we have is to preserve the valuable contents for posterity. Yet it is one hundred times better than its original. We have devoted a great deal of our time, money, and energy to improve it. The entire work was recomposed on computer. Figures [pictures] were scanned and inserted. Diacritical marks were provided as far as possible. References to citations were given in certain cases. But when a vessel is already too dirty it is very difficult to clean it even in a dozen attempts. The original was an assemblage of scattered articles written by specialists in their own field. Some were extracted from publications already published. It was issued as a special number of a journal. It needed a competent editor. Even that too was not adequate unless the editor possessed sufficient knowledge of and full competence in all the subject areas covered. One way to make it correct and complete was to prepare a kind of draft and circulate it among all the writers, or among those who could critically examine a particular paper in their respective field. -

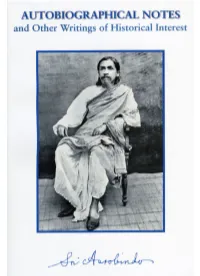

Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest

VOLUME36 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO ©SriAurobindoAshramTrust2006 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, August 1911 Publisher’s Note This volume consists of (1) notes in which Sri Aurobindo cor- rected statements made by biographers and other writers about his life and (2) various sorts of material written by him that are of historical importance. The historical material includes per- sonal letters written before 1927 (as well as a few written after that date), public statements and letters on national and world events, and public statements about his ashram and system of yoga. Many of these writings appeared earlier in Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on the Mother (1953) and On Himself: Com- piledfromNotesandLetters(1972). These previously published writings, along with many others, appear here under the new title Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest. Sri Aurobindo alluded to his life and works not only in the notes included in this volume but also in some of the letters he wrote to disciples between 1927 and 1950. Such letters have been included in Letters on Himself and the Ashram, volume 35 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. The autobiographical notes, letters and other writings in- cluded in the present volume have been arranged by the editors in four parts. The texts of the constituent materials have been checked against all relevant manuscripts and printed texts. The Note on the Texts at the end contains information on the people and historical events referred to in the texts. -

REACH “For One’S Own Liberation and for the Newsletter of Vedanta Centres of Australia Welfare of the World.” 2 Stewart Street, Ermington, NSW 2115, Australia, P.O

Motto: Atmano mokshartham jagad hitaya cha, REACH “For one’s own liberation and for the Newsletter of Vedanta Centres of Australia welfare of the world.” 2 Stewart Street, Ermington, NSW 2115, Australia, P.O. Box 3101, Monash Park, NSW 2111 Website: www.vedantasydney.org; e-mail: [email protected]; Phones: (02) 8197 7351, -52; Fax: (02) 9858 4767. Salutation be to You, O Narayani, O You Who are intent on saving the dejected and distressed that take refuge under You. O You, Devi Who remove the sufferings of all. May the Divine Mother Shower blessings on us all. Sayings and Teachings The Bhavatarini Kali Temple at Dakshineswar, Kolkata, West Bengal, India, where Sri Ramakrishna attained perfection worshipping the Divine Mother Kali (inset). Continue Meditation always “After the Chosen Ideal is brought page 225; Ramakrishna-Vivekananda of thought. We have one common and seated on the lotus of the heart, Centre of New York, U.S. goal, and that is the perfection of the sacrificial lamp of meditation the human soul, the god within us. on Him should always be kept Thoughts might differ, not the Goal --- Swami Vivekananda, burning. While one is engaged in We must learn to love the man who worldly duties, one should watch at differs from us in opinion. We must The Complete works of Swami intervals whether that lamp is burning learn that differentiation is the life Vivekananda, Volume 1X, page 487; within or not.” Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata, India. --- Sri Ramakrishna. CALENDAR OF EVENTS FROM OCTOBER TO DECEMBER 2009 Sri Ramakrishna:The Great Master Centre Volume I by Swami Saradananda, page Function Date 429; Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, Durga Puja Sydney Saturday, 26 September 2009 Chennai, India. -

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda Swami Vivekananda (Bengali: [ʃami bibekanɔndo] ( listen); 12 January 1863 – 4 Swami Vivekananda July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (Bengali: [nɔrendronatʰ dɔto]), was an Indian Hindu monk, a chief disciple of the 19th-century Indian mystic Ramakrishna.[4][5] He was a key figure in the introduction of the Indian philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world[6][7] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a major world religion during the late 19th century.[8] He was a major force in the revival of Hinduism in India, and contributed to the concept of nationalism in colonial India.[9] Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission.[7] He is perhaps best known for his speech which began, "Sisters and brothers of America ...,"[10] in which he introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893. Born into an aristocratic Bengali Kayastha family of Calcutta, Vivekananda was inclined towards spirituality. He was influenced by his guru, Ramakrishna, from whom he learnt that all living beings were an embodiment of the divine self; therefore, service to God could be rendered by service to mankind. After Vivekananda in Chicago, September Ramakrishna's death, Vivekananda toured the Indian subcontinent extensively and 1893. On the left, Vivekananda wrote: acquired first-hand knowledge of the conditions prevailing in British India. He "one infinite pure and holy – beyond later travelled to the United States, representing India at the 1893 Parliament of the thought beyond qualities I bow down World's Religions. Vivekananda conducted hundreds of public and private lectures to thee".[1] and classes, disseminating tenets of Hindu philosophy in the United States, Personal England and Europe. -

Thevedanta Kesari March 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari March 2020 1 Bengaluru’s Cover Story Floral Tribute to Swami Vivekananda page 11 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 March of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Vivekananda Navaratri, 2020 in Vivekananda House, Chennai Swami Vivekananda’s 9-day stay in Castle Kernan, Chennai, now known as Vivekananda House is celebrated every year as Vivekananda Navaratri by Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Tamil Nadu. PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 3 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS MARCH 2020 tory er ov C 11S Bengaluru’s Floral Tribute to Swami Vivekananda Suresh Moona 49 16 Should India Be a FEATURES Allama Prabhu Wholly Secular State? Shivanand Shahapur 8 Atmarpanastuti Swami Madhavananda 9 Yugavani Sri Ramakrishna and the 10 Editorial Swami Vivekananda’s Pilgrimage Mindset 14 Reminiscences First Chicago Speech in Swami Chidekananda 27 Vivekananda Way Major Local Newspapers 33 Pocket Tales Asim Chaudhuri 52 Pariprasna 53 The Order on the March 45 20 Sri Yogananda-Dashakam Poorva: Magic, Miracles Swami Japasiddhananda and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath 36 31 Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

Swamiji and Madame Calvé

Swamiji and Madame Calvé By Swami Tathagatananda Madame Emma Calvé, the celebrated singer, was in Chicago with the Metropolitan Opera Company in 1894. The world was at her feet. Calvé, the toast of two continents, was seen by her flamboyant admirers and the celebrities composing the cream of society as a bright new star sailing forth to conquer the world. One evening in the opera, she had the worst attack of stage fright she had ever experienced. She was still feeling nervous as she stepped onto the stage after the first intermission, even though the first act had been a tremendous success. She felt terribly depressed and thought of giving up the rest of her performance that night. She barely staggered from her dressing room to the wings, where she stood frozen as though paralyzed. Persuaded by the manager to go on the stage, she sang magnificently in the second act. Returning to her dressing room during the second intermission, she virtually collapsed. She felt overwhelmingly depressed and had difficulty breathing. She requested the manager to announce to the audience her inability to perform because of illness. However, with the assistance of others nearby, the manager nearly carried her to the stage for the third and last act. Making the greatest effort of her life, she completed her role and received tremendous applause for one of the most glorious performances of her entire career. But her mind was still consumed by a strange foreboding of some impending grave peril. Running to her room after this rousing ovation, a solemn reception of several grave faces was waiting for her. -

New Arrivals May 2017

AMRITA VISHWA VIDYAPEETHAM UNIVERSITY AMRITAPURI CAMPUS CENTRAL LIBRARY NEW ARRIVALS BOOK MAY 2017 Sl. Acc. No Title Author Subject A bridge to eternity: Sri Ramakrishna and 1 48274 his monastic order Spiritual 2 48253 A Handbook of Ashtanga Sangraha VIDYANATH,R Spiritual A New Earth:Awakening to Your Life"s 3 48209 Purpose Tolle,Eckhart Spiritual Chattambi Swamikal, Advaita Cinta Paddhati :The Essence of Thiruvadikal 4 48281 Advaita Vidyadhiraja Spiritual Yatiswarananda, 5 48268 Adventures in Religious Life Swami Spiritual GAMBHIRANANDA 6 48277 Aitareya Upanisad Tr Spiritual Atmaramananda, 7 48189 Art Culture and Spirituality Swami Spiritual Ashokananda,Swa 8 48261 Avadhuta Gita mi Spritual 9 48258 Be the self Ganesan ,V Spiritual Beyond Duality: Biographical Sketches of Saint & Enlightened Spiritual Teachers of Williams,Norman 10 48279 the 20th Centuary comp. Spritual 11 48290 Bhagavatha Vahini Sathya Sai Baba Spiritual Bhajanamritam - 2 : Malayalam Devotional 12 48204 Songs of Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi Spiritual 13 48221 Bhakti: Means and the end Rama Devi Spiritual 14 48252 revelation ROY, Thomas Spiritual Breaking India:Western Interventions in 15 48202 Dravidian and Dalit Faultliness Malhotra, Rajiv Spiritual 16 48297 Condensed gospel of Sri Ramakrishna Sri Ramakrishna Spiritual 17 48269 Dakshinamurti Stotra Sankaracharya Spiritual JAGADISWARANA 18 48264 Devi Mahatmyam NDA, Swami Spiritual 19 48217 Discipleship and sadhana Tara Devi Spiritual Gambhirananda, 20 48267 Eight Upanisads Swami Spiritual From Holy Wanderings to the