Legacy of Swami Vivekananda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters (Fifth Series) Lectures and Discourses Notes of Lectures and Classes Writings: Prose and Poems (Original and Translated) Conversations and Interviews Excerpts from Sister Nivedita's Book Sayings and Utterances Newspaper Reports Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters - Fifth Series I Sir II Sir III Sir IV Balaram Babu V Tulsiram VI Sharat VII Mother VIII Mother IX Mother X Mother XI Mother XII Mother XIII Mother XIV Mother XV Mother XVI Mother XVII Mother XVIII Mother XIX Mother XX Mother XXI Mother XXII Mother XXIII Mother XXIV Mother XXV Mother XXVI Mother XXVII Mother XXVIII Mother XXIX Mother XXX Mother XXXI Mother XXXII Mother XXXIII Mother XXXIV Mother XXXV Mother XXXVI Mother XXXVII Mother XXXVIII Mother XXXIX Mother XL Mrs. Bull XLI Miss Thursby XLII Mother XLIII Mother XLIV Mother XLV Mother XLVI Mother XLVII Miss Thursby XLVIII Adhyapakji XLIX Mother L Mother LI Mother LII Mother LIII Mother LIV Mother LV Friend LVI Mother LVII Mother LVIII Sir LIX Mother LX Doctor LXI Mother— LXII Mother— LXIII Mother LXIV Mother— LXV Mother LXVI Mother— LXVII Friend LXVIII Mrs. G. W. Hale LXIX Christina LXX Mother— LXXI Sister Christine LXXII Isabelle McKindley LXXIII Christina LXXIV Christina LXXV Christina LXXVI Your Highness LXXVII Sir— LXXVIII Christina— LXXIX Mrs. Ole Bull LXXX Sir LXXXI Mrs. Bull LXXXII Mrs. Funkey LXXXIII Mrs. Bull LXXXIV Christina LXXXV Mrs. Bull— LXXXVI Miss Thursby LXXXVII Friend LXXXVIII Christina LXXXIX Mrs. Funkey XC Christina XCI Christina XCII Mrs. Bull— XCIII Sir XCIV Mrs. Bull— XCV Mother— XCVI Sir XCVII Mrs. -

Divya Sandesha

DIVYA SANDESHA Pujya Shri Ramchandraji Maharaj’s (Shri Babuji) letters to Sri S.A.Sarnadji Divya Sandesh: A Collection of letters of Pujya Shri Ramchandraji Maharaj (Shri Babuji) of Shahjahanpur to Shri (Late) S.A.Sarnadji, edited by Smt. Shakuntala Bai Sarnad and published by Shree Prakashana, NGO Colony, Jewargi Road, Gulbarga. PUBLISHER’S NOTE After the demise of Sri S.A.Sarnadji, while searching the papers of old house at our village and other immoveable property, we could find a bunch of letters and few Sanskrit books kept safely. These letters are in Urdu, Hindi and English. We learnt that Urdu letters are written/got written by Pujya Babuji Maharaj to Sarnadji. The other letters are written by Sri Ishwar Sahaji, Sri Raghavendra Raoji and Dr. K.C Vardachariji. We were inspired by these letters and thought of publishing Pujya Babuji’s letters with translations so as abhyasi brothers and sisters would be benifited and they can see the original hand writings of a great special personality Pujya Babuji Maharaj. We felt irrelevent since these letters are written to Sarnadji in a personal capacity and not as an office bearer. Probably Sarnadji must have thought likewise and did not take any interst in this regard and moreover none of our family members was aware of these letters. Though these letters are personal, the need to publish the letters with translations was felt to enable the true seekers of spirituality to perceive the message of love, advice and guidance embodied therein lest these letters written in formative years of a Sadhaka with humility, compassion and concern by Pujaya Babuji Maharaj may be lost for ever. -

The Greatness of Misery

The Greatness of Misery Swami Chetanananda People generally love joyful stories with happy endings. But human life consists of happiness and misery, comedy and tragedy. Even when divine beings take human forms, they must obey this law of maya. Because happiness and misery are inevitable in human life, avatars accept this fact but are not affected by it. Most of the time, their minds dwell in their divine nature, which is above the pairs of opposites. They take human birthto teach ordinary people how to face problems and suffering, maintain peace and harmony, and experience divine bliss by leading a God-‐‑centred life. In every age, when religion declines and irreligion prevails, avatars come to reestablish the eternal religion. But they do not come alone. They are aended by their spiritual companions: For example, Ramachandra came with Sita, Krishna with Radha, Buddha with Yashodhara, Chaitanya with Vishnupriya, and Ramakrishna with Sarada. As the birds cannot fly with one wing, so avatars are accompanied by their Shakti, theirfemale counterpart. These spiritual consorts carry the avatar’s spiritual message and serve as an inspiration for others. Sita suffered throughout her life; and she taught how to forbear suffering by keeping her mind in herbeloved Rama. Radha tried to forget her pain of separation from Krishnaby focussing on her longing and passion for him. When Buddha left, Yashodhara was grief-‐‑stricken. She raised their son and led a nun’s life in the palace. She forgot her pain by practising renunciation and thinking of the impermanency of the world. Vishnupriya accepted Chaitanya’s wish to be a monk, releasing her husband to be a world teacher. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Expand Your Heart – Vkjuly19

1 TheVedanta Kesari July 2019 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story page 11... 1 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly `15 July of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2019 TheTheVedanta Kesari Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004 h(044) 2462 1110 E-mail: [email protected] Website : www.chennaimath.org DearDea Readers, TThe Vedanta Kesari is one of the oldest cultural aandnd sspiritual magazines in the country. Started under tthehe gguidance and support of Swami Vivekananda, the ffirstirs issue of the magazine, then called BBrahmavadinr , came out on 14 Sept 1895. July 2019 BrBrahmavadin was run by one of Swamiji’s ardent ffollowersol Sri Alasinga Perumal. After his death in 4 1190990 the magazine publication became irregular, aandnd stoppeds in 1914 whereupon the Ramakrishna OOrder revived it as The Vedanta Kesari. Swami Vivekananda’s concern for the mmagazine is seen in his letters to Alasinga Perumal whwheree he writes: ‘Now I am bent upon starting the journal.’ ‘Herewith I send a hundred dollars…. Hope this will go just a little in starting your The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta paper.’ ‘I am determined to see the paper succeed.’ ‘The Song of the Sannyasin is my first contribution for your journal.’ ‘I learnt from your letter the bad financial state that Brahmavadin is in.’ ‘It must be supported by the Hindus if they have any sense of virtue or gratitude left in them.’ ‘I pledge myself to maintain the paper anyhow.’ ‘The Brahmavadin is a jewel—it must not perish. Of course, such a paper has to be kept up by private help always, and we will do it.’ For the last 105 years, without missing a single issue, the magazine has been carrying the invigorating message of Vedanta with articles on spirituality, culture, philosophy, youth, personality development, science, holistic living, family and corporate values. -

VIVEKANANDA and the ART of MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1

VIVEKANANDA AND THE ART OF MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1 1. Episodes from Vivekananda’s life 2. Episodes from Ramakrishna’s life 3. Their memory power compared by Swami Saradananda 4. Other srutidharas from the past 5. The ancient art of memory 6. The laws of memory 7. The role of memory in daily life Episodes from Vivekananda’s life The human problem is one of memory. We have forgotten our divine nature. All the great teachers of the past have declared that the revival of the memory of our divinity is the paramount goal. Memory is a faculty and as such, it is neither good nor bad. Every action that we do, every thought that we think, leaves an indelible trail of memory. Whether we remember or not, the contents are recorded and affect our daily life. Therefore, an awareness of this faculty and its method of operation is vital for healthy existence. Properly employed, it leads us to enlightenment; abused or misused, it can torment us. So we must learn to use it properly, to strengthen it for our own improvement. In studying the life of Vivekananda, we come across many phenomenal examples of his amazing faculty of memory. In ‘Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda,’ Haripada Mitra relates the following story: One day, in the course of a talk, Swamiji quoted verbatim some two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. I wondered at this, not understanding how a sanyasin could get by heart so much from a secular book. I thought that he must have read it quite a number of times before he took orders. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Hollywood Temple Santa Barbara Temple Ramakrishna Monastery

HOLLYWOOD TEMPLE Fridays 7:30 PM SANTA BARBARA TEMPLE RAMAKRIshNA MONAstERY 1946 Vedanta Place 10, 17, 24, 31 Eternal Words of Sw. Adbhutananda 19961 Live Oak Canyon Road 927 Ladera Lane PO Box 408, Trabuco Canyon, Hollywood, CA 90068 Santa Barbara, CA 93108 CA 92678 949 858 0342 323 465 7114 Saturday 2:30 PM 805 969 2903 Daily Visiting Hours 4, 11 Temple Hours 6:30 AM– 7 pm Chanting for Beginners Temple Hours 9–11 AM, 3–5 pm Bookshop Hours 6:30 AM– 7 pm Bookshop Hours Mon–Sat 10 AM–12:30 pm Sundays 9–10:35 AM Bookshop Hours Mon–Fri 9 AM–11 AM, 2–5 pm Sanskrit Class Mon–Sat 11 AM–5 pm 3 PM–5 PM; Sun 10 AM–1 pm Sat & Sun 10 AM–5 PM Sun 10–11 AM, Noon–5 pm Sukirtha Alagarswamy Santa barbara Orange County Hollywood Bookshop Closed Wednesdays Bookshop Closed Tuesdays Bookshop Closed Wednesdays MAY 2019 MAY 2019 MAY 2019 Sundays/Domingos 2:30 PM Sunday Spiritual Talks 11 am Sunday Spiritual Talks 11 am Sunday Spiritual Talks 11 am Spanish Scripture Class Swami Dhyanayogananda 5 Spiritual Talk 5 Vedanta for Mental Wellness 5 Two Drops of Nectar (in person or live video) Swami Atmapriyananda Swami Tadananda, Ramakrishna Mission, Fiji Swami Sarvadevananda Vivekananda University, India 12 The Nature of Nirvana • Other Events • Swami Satyamayananda 12 The Narcissus Complex 12 Two Drops of Nectar Swami Vedarupananda Swami Sarvadevananda 19 Seeking Fellowship vs Seeking Solitude 1 Wed. 7:30 PM Jaya Row, Vedanta Vision 19 Lifelong Learning Swami Dhyanayogananda 19 The Nature of Nirvana Ancient Indian Wisdom—Modern Perspective Pravrajika Vrajaprana Swami Satyamayananda 26 Two Drops of Nectar 2 Thursday 7:30 PM Swami Tadananda, Fiji 26 The Nature of Nirvana Swami Sarvadevananda 26 The Cultivation of Dexterity Maya Swami Satyamayananda in our Daily Life • Other Events • 3 Friday 7:30 PM Swami Atmapriyananda Swami Chandrashekharananda Vivekananda University, India • Other Events • 2 Thursday 7:30 PM Swami Atmapriyananda Vedanta Society of Portland Spiritual Talk Vivekananda University, India Spiritual Talk 8 Wed. -

Shraddha's Book

1 The Beautiful Lady of my dream 2 A Danda Swami’s Tribute conveyed to the author by Swami Mangalananda Giri Something interesting happened that you will appreciate. An 84-year-old Danda Swami is staying at the ashram during the rains. He speaks very good English and frequently comes to my room. He asked for any book about Ma, and I told him to browse my “library” which now extends the full length of one wall. Without any prompting from me, he went directly to your book “In Her Perfect Love”, and I gladly lent it to him. After a day he came back and was literally raving about the book. He said, ‘If I sold everything in the world, it would not pay the price of this book. I’ve been mad for this book since I started it - reading it day and night.’ I told him I communicated with you and would pass on his enthusiasm. Swami Mangalananda Contents Introduction………………………………………… 4 Acknowledgement………………………………….. 6 Swamiji’s Blessing…………………………… 7 Foreword ............................................... ...................... 8 First Darshan(1960) ........................................................10 First Trip (November 6, 1970-November 20, 1970) Suktal ................................................................ 14 Kanpur ............................................................... .17 Second Trip (May 9, 1971-May 30, 1971) Varanasi ............................................................. .23 Vrindavan ............................................................ 28 Delhi .................................................................. -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

Halasuru Math Book List

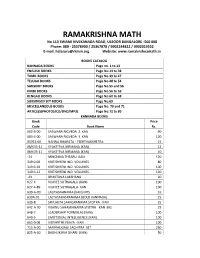

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

“ That This House, on the 150Th Birth Anniversary of Swami Vivekananda

The year 2013 is a very important year in the eventful calendar of the Ramakrishna Mission. This year happens to be the 150th Birthday Anniversary of Swami Vivekanada. Swamiji, as we call him, life’s mission was to propagate the teachings of the Vedanta, in the light of realisation of Sri Ramakrishna who is his master, throughout the world. “Swamiji has left behind a rich legacy for the future generations, in his writings on the four yogas, speeches, poetic compositions, epistles etc are in his book of complete works of Swami Vivekanda.” His birthday celebration has been celebrated throughout the world, of note in January 2013 UK Parliament recognised the valuable contribution made by Swamaji. The statement from the UK Parliament is: “ That this House, on the 150th Birth Anniversary of Swami Vivekananda, recognises the valuable contribution made by him to interfaith dialogue at international level, encouraging and promoting harmony and understanding between religions through his renowned lectures and presentations at the first World Parliament of the Religions in Chicago in 1893, followed by his lecture tours in the US and England and mainland Europe; notes that these rectified and improved the understanding of the Hindu faith outside India and dwelt upon universal goodness found within all religions; further notes that he inspired thousands to selflessly serve the distressed and those in need and promoted an egalitarian society free of all kinds of discrimination; and welcome the celebrations of his 150th Birth Anniversary in the UK and throughout the World” Vedanta Society, Brisbane Chapter celebrated the 150th Birthday Celebration and the 176th Birthday Celebration of Sri Ramakrishna on the 9th March 2013.