Viol a Fre Y : Center S T a Ge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wanxin Zhang Zhang | Totem with an Exhibition of Life-Size Ceramic Sculptures

San Francisco, CA: Catharine Clark Gallery presents Wanxin Wanxin Zhang Zhang | Totem with an exhibition of life-size ceramic sculptures. Totem is deeply inspired by Zhang’s upbringing Totem in Maoist China, his subsequent disillusionment, and his ultimate relocation to California as a young artist in the 1990s. The work in the exhibit reflects both a geographical November 8, 2014 – January 3, 2015 journey and an ideological search. Totem demonstrates Zhang’s mastery of the malleable and expressive qualities of Join us for an opening with the artist clay to disrupt and reshape both the form and meaning of on Saturday, November 8 traditional symbols and icons. from 4:00-6:00 pm Zhang’s new monumental clay figures feature the artist’s signature style—a blend that reflects Bay Area Figurative and California Funk traditions with nods to Chinese history. Inspired by his time studying with Peter Voulkous, and by the innovations of Robert Arneson and Stephen De Staebler, Zhang’s figures explore the organic, evocative qualities of clay, and the impact of popular culture on the body. Pink Warrior (2014) exemplifies the departure and hybridity in Zhang’s new work: an androgynous soldier coated in a glossy bubble-gum pink sheen; face and body a landscape of finger prints, gouges, coils and layers; inscripted with individual emotion rather than blank anonymity. This warrior retains the freeform construction and visual weight Wanxin Zhang of Zhang’s well known Pit #5 series, but is an entirely new The Refluent Tide ensign of power structure dismantlement. Zhang’s Pieta 2014 figures further exemplify the cross-cultural reshaping unique 24 x 24 x 32 inches to the artist’s aesthetic. -

February 1992 1 William Hunt

February 1992 1 William Hunt................................................. Editor Ruth C. Butler ...............................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager ................................ Art Director Kim S. Nagorski............................ Assistant Editor Mary Rushley........................ Circulation Manager MaryE. Beaver.......................Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher ...................... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis ......................................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, announcements and news releases about ceramics are welcome and will be consid ered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A booklet describing standards and proce dures for submitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Addition ally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) indexing is available through Wilsonline, 950 UniversityAve., Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Co., 362 Lakeside Dr., Forest City, Califor nia 94404. -

Viola Frey……………………………………………...6

Dear Educator, We are delighted that you have scheduled a visit to Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Vila Frey. When you and your students visit the Museum of Arts and Design, you will be given an informative tour of the exhibition with a museum educator, followed by an inspiring hands-on project, which students can then take home with them. To make your museum experience more enriching and meaningful, we strongly encourage you to use this packet as a resource, and work with your students in the classroom before and after your museum visit. This packet includes topics for discussion and activities intended to introduce the key themes and concepts of the exhibition. Writing, storytelling and art projects have been suggested so that you can explore ideas from the exhibition in ways that relate directly to students’ lives and experiences. Please feel free to adapt and build on these materials and to use this packet in any way that you wish. We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Museum of Arts and Design. Sincerely, Cathleen Lewis Molly MacFadden Manager of School, Youth School Visit Coordinator And Family Programs Kate Fauvell, Dess Kelley, Petra Pankow, Catherine Rosamond Artist Educators 2 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 P 212.299.7777 F 212.299.7701 MADMUSEUM.ORG Table of Contents Introduction The Museum of Arts and Design………………………………………………..............3 Helpful Hints for your Museum Visit………………………………………….................4 Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Viola Frey……………………………………………...6 Featured Works • Group Series: Questioning Woman I……………………………………………………1 • Family Portrait……………………………………………………………………………..8 • Double Self ……………………………………………………………………...............11 • Western Civilization Fountain…………………………………………………………..13 • Studio View – Man In Doorway ………………………………………………………. -

Oral History Interview with Robert David Brady

Oral history interview with Robert David Brady Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Robert David Brady -

03–04 Department of Infrastructure Annual Report I

03–04 Department of Infrastructure Annual Report i Annual Report 2003–04 29 October 2004 The Hon. Peter Batchelor MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects The Hon. Theo Theophanous MLC Minister for Energy Industries and Resources The Hon. Marsha Thomson MLC Minister for Information and Communication Technology 80 Collins Street Melbourne 3000 www.doi.vic.gov.au Dear Ministers Annual Report 2003–04 In accordance with the provisions of the Financial Management Act 1994, I have pleasure in submitting for presentation to Parliament the Department of Infrastructure Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2004. Yours sincerely Howard Ronaldson Secretary Department of Infrastructure ii Published by Corporate Public Affairs Department of Infrastructure Level 29, 80 Collins Street, Melbourne October 2004 Also published on www.doi.vic.gov.au © State of Victoria 2004 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 Authorised by the Victorian Government, 80 Collins Street, Melbourne Printed by Finsbury Press, 46 Wirraway Drive, Port Melbourne, Victoria iii Secretary’s Foreword It has been a busy year for the Department of Infrastructure system. The Metropolitan Transport Plan is due for (DOI) portfolio. release in the near future Notable achievements for 2003–04 include: • a stronger emphasis on safety and security across the portfolio, particularly in rail • the establishment of stable commercial arrangements for the conduct of urban train -

Oral History Interview with Viola Frey, 1995 Feb. 27-June 19

Oral history interview with Viola Frey, 1995 Feb. 27-June 19 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Viola Frey on February 27, May 15 & June 19, 1995. The interview took place in oakland, CA, and was conducted by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Session 1, Tape 1, Side A (30-minute tape sides) PAUL KARLSTROM: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. An interview with Viola Frey at her studio in Oakland, California, February 27, 1995. The interviewer for the Archives is Paul Karlstrom and this is what we hope will be the first in a series of conversations. It's 1:35 in the afternoon. Well, Viola, this is an interview that has waited, I think, about two or three years to happen. When I first visited you way back then I thought, "We really have to do an interview." And it just took me a while to get around to it. But at any rate what I would like to do is take a kind of journey back in time, back to the beginning, and see if we can't get some insight into, of course, who you are, but then where these wonderful works of art come from, perhaps what they mean. -

Bay-Area-Clay-Exhibi

A Legacy of Social Consciousness Bay Area Clay Arts Benicia 991 Tyler Street, Suite 114 Benicia, CA 94510 Gallery Hours: Wednesday-Sunday, 12-5 pm 707.747.0131 artsbenicia.org October 14 - November 19, 2017 Bay Area Clay A Legacy of Social Consciousness Funding for Bay Area Clay - a Legacy of Social Consciousness is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. A Legacy of Social Consciousness I want to thank every artist in this exhibition for their help and support, and for the powerful art that they create and share with the world. I am most grateful to Richard Notkin for sharing his personal narrative and philosophical insight on the history of Clay and Social Consciousness. –Lisa Reinertson Thank you to the individual artists and to these organizations for the loan of artwork for this exhibition: The Artists’ Legacy Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY for the loan of Viola Frey’s work Dolby Chadwick Gallery and the Estate of Stephen De Staebler The Estate of Robert Arneson and Sandra Shannonhouse The exhibition and catalog for Bay Area Clay – A Legacy of Social Consciousness were created and produced by the following: Lisa Reinertson, Curator Arts Benicia Staff: Celeste Smeland, Executive Director Mary Shaw, Exhibitions and Programs Manager Peg Jackson, Administrative Coordinator and Graphics Designer Jean Purnell, Development Associate We are deeply grateful to the following individuals and organizations for their support of this exhibition. National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

NEWS and COMMENT Florida Legislators, FSU

NEWS AND COMMENT Florida Legislators, the deal on academic and scientific only way to combat this is to ensure that grounds.) After a protracted fight, York government leaders and media professionals FSU Faculty Clash over rejected the proposal in 2001. receive adequate scientific training based on Proposed Chiropractic reason, and that they also develop critical —John Gaeddert School at University thinking skills." John Gaeddert is Assistant Director of Public Ostrander traces the popularity of crude A proposed chiropractic school at Florida Relations for CSICOP. shark cartilage as a cancer treatment and pre- State University (FSU) has pitted state legis- ventive measure to I. William Lane's 1992 lators against school faculty in a battle that is book tided Sharks Don't Get Cancer, which equal parts science and politics. Shark Cartilage Cancer was further publicized by the CBS News pro- 'Cure' Shows Danger of gram 60 Minutes in 1993. Though Lane acknowledges in the book that sharks do, in Pseudoscience fact, get cancer, he bases his advocacy of crude cartilage extracts on what Ostrander The rising popularity of shark cartilage calls "overextensions" of some early experi- extract as an anti-cancer treatment is a tri- ments in which the substance seemed to In January, FSU considered a proposal to umph of marketing and pseudoscience over inhibit tumor formation and the growth of build the first public chiropractic school in reason, with a tragic fallout for both sharks new blood vessels that supply nutrients and the country. Florida Governor Jeb Bush and and humans, according to a Johns Hopkins the state legislature have already set aside $9 biologist writing in the December 1, 2004, oxygen to malignancies. -

People. Passion . Power

PEOPLE. PASSION. POWER. A Special Edition Generations People, passion, and power When you set out to write a book, you should always know why. Writing a book is a big job, especially when there is a big story to tell, like the one of innovation in ABB’s marine and ports business. When we decided to produce a spe- is our motivation, and the catalyst to cial edition of our annual publication growth in our industry. Generations, it was to acknowledge Though we live and work on the customers who have served as the leading edge, we recognise that our inspiration, to share the ABB spirit lessons learned along the way have of striving to learn, develop and innov- formed the foundation for ABB’s ate, but also to say thank you to the current success. By sharing these people who have worked to make our lessons, we hope to raise the under- success possible. standing of our unique approach to Innovation can be defined as marine and ports innovation. The mar- something original and more effective ine and ports segment also reflects and, as a consequence, something ABB’s corporate history, with its roots new that ‘breaks into’ the market. in the national industrial conglomer- Innovation can be viewed as the ap- ates of four countries, merging and plication of better solutions that meet emerging with the goal of becoming new requirements or market needs. ‘One ABB’. This is achieved through more effect- We hope you enjoy reading about ive products, processes, services, the remarkable people of ABB’s mar- technologies, and ideas. -

A Look at Upcoming Exhibits and Performances Page 34

Vol. XXXIV, Number 50 N September 13, 2013 Moonlight Run & Walk SPECIAL SECTION page 20 www.PaloAltoOnline.com A look at upcoming exhibits and performances page 34 Transitions 17 Spectrum 18 Eating 29 Shop Talk 30 Movies 31 Puzzles 74 NNews Council takes aim at solo drivers Page 3 NHome Perfectly passionate for pickling Page 40 NSports Stanford receiving corps is in good hands Page 78 2.5% Broker Fee on Duet Homes!* Live DREAM BIG! Big Home. Big Lifestyle. Big Value. Monroe Place offers Stunning New Homes in an established Palo Alto Neighborhood. 4 Bedroom Duet & Single Family Homes in Palo Alto Starting at $1,538,888 410 Cole Court <eZllb\lFhgkh^IeZ\^'\hf (at El Camino Real & Monroe Drive) Palo Alto, CA 94306 100&,,+&)01, Copyright ©2013 Classic Communities. In an effort to constantly improve our homes, Classic Communities reserves the right to change floor plans, specifications, prices and other information without prior notice or obliga- tion. Special wall and window treatments, custom-designed walks and patio treatments and other items featured in and around the model homes are decorator-selected and not included in the purchase price. Maps are artist’s conceptions and not to scale. Floor plans not to scale. All square footages are approximate. *The single family homes are a detached, single-family style but the ownership interest is condominium. Broker # 01197434. Open House | Sat. & Sun. | 1:30 – 4:30 27950 Roble Alto Drive, Los Altos Hills $4,250,000 Beds 5 | Baths 5.5 | Offices 2 | Garage 3 Car | Palo Alto Schools Home ~ 4,565 sq. -

Bennett Bean Playing by His Rules by Karen S

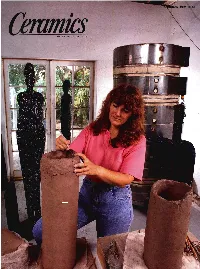

March 1998 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 1998 Volume 46 Number 3 Wheel-thrown stoneware forms by Toshiko Takaezu at the American Craft FEATURES Inlaid-slip-decorated Museum in vessel by Eileen New York City. 37 Form and Energy Goldenberg. 37 The Work of Toshiko Takaezu by Tony Dubis Merino 75 39 George Wright Oregon Potters’ Friend and Inventor Extraordinaire by Janet Buskirk 43 Bennett Bean Playing by His Rules by Karen S. Chambers with Making a Bean Pot 47 The Perfect Clay Body? by JejfZamek A guide to formulating clay bodies 49 A Conversation with Phil and Terri Mayhew by Ann Wells Cone 16 functional porcelain Intellectually driven work by William Parry. 54 Collecting Maniaby Thomas G. Turnquist A personal look at the joy pots can bring 63 57 Ordering Chaos by Dannon Rhudy Innovative handbuilding with textured slabs with The Process "Hair of the Dog" clay 63 William Parry maker George Wright. The Medium Is Insistent by Richard Zakin 39 67 David Atamanchuk by Joel Perron Work by a Canadian artist grounded in Japanese style 70 Clayarters International by CarolJ. Ratliff Online discussion group shows marketing sawy 75 Inspirations by Eileen P. Goldenberg Basket built from textured Diverse sources spark creativity slabs by Dannon Rhudy. The cover: New Jersey 108 Suggestive Symbols by David Benge 57 artist Bennett Bean; see Eclectic images on slip-cast, press-molded sculpture page 43. March 1998 3 UP FRONT 12 The Senator Throws a Party by Nan Krutchkoff Dinnerware commissioned from Seattle ceramist Carol Gouthro 12 Billy Ray Hussey EditorRuth