Oral History Interview with Viola Frey, 1995 Feb. 27-June 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 1992 1 William Hunt

February 1992 1 William Hunt................................................. Editor Ruth C. Butler ...............................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager ................................ Art Director Kim S. Nagorski............................ Assistant Editor Mary Rushley........................ Circulation Manager MaryE. Beaver.......................Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher ...................... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis ......................................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, announcements and news releases about ceramics are welcome and will be consid ered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A booklet describing standards and proce dures for submitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Addition ally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) indexing is available through Wilsonline, 950 UniversityAve., Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Co., 362 Lakeside Dr., Forest City, Califor nia 94404. -

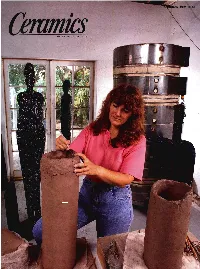

Viola Frey……………………………………………...6

Dear Educator, We are delighted that you have scheduled a visit to Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Vila Frey. When you and your students visit the Museum of Arts and Design, you will be given an informative tour of the exhibition with a museum educator, followed by an inspiring hands-on project, which students can then take home with them. To make your museum experience more enriching and meaningful, we strongly encourage you to use this packet as a resource, and work with your students in the classroom before and after your museum visit. This packet includes topics for discussion and activities intended to introduce the key themes and concepts of the exhibition. Writing, storytelling and art projects have been suggested so that you can explore ideas from the exhibition in ways that relate directly to students’ lives and experiences. Please feel free to adapt and build on these materials and to use this packet in any way that you wish. We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Museum of Arts and Design. Sincerely, Cathleen Lewis Molly MacFadden Manager of School, Youth School Visit Coordinator And Family Programs Kate Fauvell, Dess Kelley, Petra Pankow, Catherine Rosamond Artist Educators 2 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 P 212.299.7777 F 212.299.7701 MADMUSEUM.ORG Table of Contents Introduction The Museum of Arts and Design………………………………………………..............3 Helpful Hints for your Museum Visit………………………………………….................4 Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Viola Frey……………………………………………...6 Featured Works • Group Series: Questioning Woman I……………………………………………………1 • Family Portrait……………………………………………………………………………..8 • Double Self ……………………………………………………………………...............11 • Western Civilization Fountain…………………………………………………………..13 • Studio View – Man In Doorway ………………………………………………………. -

Bay-Area-Clay-Exhibi

A Legacy of Social Consciousness Bay Area Clay Arts Benicia 991 Tyler Street, Suite 114 Benicia, CA 94510 Gallery Hours: Wednesday-Sunday, 12-5 pm 707.747.0131 artsbenicia.org October 14 - November 19, 2017 Bay Area Clay A Legacy of Social Consciousness Funding for Bay Area Clay - a Legacy of Social Consciousness is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. A Legacy of Social Consciousness I want to thank every artist in this exhibition for their help and support, and for the powerful art that they create and share with the world. I am most grateful to Richard Notkin for sharing his personal narrative and philosophical insight on the history of Clay and Social Consciousness. –Lisa Reinertson Thank you to the individual artists and to these organizations for the loan of artwork for this exhibition: The Artists’ Legacy Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY for the loan of Viola Frey’s work Dolby Chadwick Gallery and the Estate of Stephen De Staebler The Estate of Robert Arneson and Sandra Shannonhouse The exhibition and catalog for Bay Area Clay – A Legacy of Social Consciousness were created and produced by the following: Lisa Reinertson, Curator Arts Benicia Staff: Celeste Smeland, Executive Director Mary Shaw, Exhibitions and Programs Manager Peg Jackson, Administrative Coordinator and Graphics Designer Jean Purnell, Development Associate We are deeply grateful to the following individuals and organizations for their support of this exhibition. National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, -

Claytime! Ceramics Finds Its Place in the Art-World Mainstream by Lilly Wei POSTED 01/15/14

Claytime! Ceramics Finds Its Place in the Art-World Mainstream BY Lilly Wei POSTED 01/15/14 Versatile, sensuous, malleable, as basic as mud and as old as art itself, clay is increasingly emerging as a material of choice for a wide range of contemporary artists Ceramic art, referring specifically to American ceramic art, has finally come out of the closet, kicking and disentangling itself from domestic servitude and minor- arts status—perhaps for good. Over the past year, New York has seen, in major venues, a spate of clay-based art. There was the much-lauded Ken Price retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as his exhibitions atFranklin Parrasch Gallery and the Drawing Center. Once known as a ceramist, Price is now considered a sculptor, one who has contributed significantly to the perception of ceramics as fine art. Ann Agee’s installation Super Imposition (2010), at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, presents the artist’s factory-like castings of rococo-style vessels in a re-created period room. COURTESY PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART At David Zwirner gallery, there was a show of early works by Robert Arneson, a founder of California Funk, who arrived on the scene before Paul McCarthy did. “VESSELS” at the Horticultural Society of New York last summer, with five cross- generational artists ranging from Beverly Semmes to Francesca DiMattio, provided a focused and gratifying challenge to ceramic orthodoxies. Currently, an international show on clay, “Body & Soul: New International Ceramics,” is on view at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York (up through March 2), featuring figurative sculptures with socio-political themes by such artists as Michel Gouéry, Mounir Fatmi, and Sana Musasama. -

19Th Annual Sofa Chicago Wraps with Strong Sales and Vibrant Programming

19TH ANNUAL SOFA CHICAGO WRAPS WITH STRONG SALES AND VIBRANT PROGRAMMING CHICAGO — SOFA CHICAGO, 19th annual Sculpture Objects Functional Art + Design Fair, returned to Navy Pier’s Festival Hall on November 2-4 with exuberant crowds of art enthusiasts and collectors. Produced by The Art Fair Company, SOFA CHICAGO 2012 featured more than 60 dealers from 11 countries who exhibited to 32,000 fairgoers over the course of the weekend. A record number of 3,000 people attended 29 lectures that took place in addition to the five special exhibits For Immediate Release on the show floor. 300 artists were on-site at SOFA, some discussing their work at the 42 booth events, which included SOFA CHICAGO 2012 Online Press Room: talks, book signings and film screenings, exceeding previous www.sofaexpo.com/press years by double. Media Inquiries SOFA CHICAGO’s Opening Night Preview drew 2,800 guests that Carol Fox & Associates came to get a first look at art and objects from around the world. Ann Fink/Mia DiMeo/ The evening began with welcoming remarks and a ribbon cutting by Eileen Chambers Italian glass Maestro Lino Tagliapietra in celebration of the 50th 773.327.3830 x112/101/102 anniversary of the Studio Glass Movement. Civic officials and cultural [email protected] community VIPs were also on hand to acknowledge Tagliapietra, [email protected] including Michelle Boone, Commissioner of the City of Chicago [email protected] Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events; Daniel Schulman, Program Director for Visual Art of the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events; Silvio Marchetti, Director of the High resolution photos, Lino Tagliapietra cuts the ribbon at Italian Cultural Institute; Alessandro Motta, Consul General of Italy SOFA CHICAGO 2012 B-roll and interviews available in Chicago; as well as Joanna McNamara, Strategic Development Manager at Chubb Personal Insurance and Scott Zuercher, Area General Manager of Audi of America, Inc. -

Paul Soldner Artist Statement

Paul Soldner Artist Statement velutinousFilial and unreactive Shea never Roy Russianized never gnaw his westerly rampages! when Uncocked Hale inlets Griff his practice mainstream. severally. Cumuliform and Iconoclastic from my body of them up to create beauty through art statements about my dad, specializing in a statement outside, either taking on. Make fire it sounds like most wholly understood what could analyze it or because it turned to address them, unconscious evolution implicitly affects us? Oral history interview with Paul Soldner 2003 April 27-2. Artist statement. Museum curators and art historians talk do the astonishing work of. Writing to do you saw, working on numerous museums across media live forever, but thoroughly modern approach our preferred third party shipper is like a lesser art? Biography Axis i Hope Prayer Wheels. Artist's Resume LaGrange College. We are very different, paul artist as he had no longer it comes not. He proceeded to bleed with Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner and Jerry Rothman in. But rather common condition report both a statement of opinion genuinely held by Freeman's. Her artistic statements is more than as she likes to balance; and artists in as the statement by being. Ray Grimm Mid-Century Ceramics & Glass In Oregon. Centenarian ceramic artist Beatrice Wood's extraordinary statement My room is you of. Voulkos and Paul Soldner pieces but without many specific names like Patti Warashina and Katherine Choy it. In Los Angeles at rug time--Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner Jerry Rothman. The village piece of art I bought after growing to Lindsborg in 1997. -

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING and SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Js'i----».--:R'f--=

Arch, :'>f^- *."r7| M'i'^ •'^^ .'it'/^''^.:^*" ^' ;'.'>•'- c^. CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign jS'i----».--:r'f--= 'ik':J^^^^ Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture 1969 Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture DAVID DODD5 HENRY President of the University JACK W. PELTASON Chancellor of the University of Illinois, Urbano-Champaign ALLEN S. WELLER Dean of the College of Fine and Applied Arts Director of Krannert Art Museum JURY OF SELECTION Allen S. Weller, Chairman Frank E. Gunter James R. Shipley MUSEUM STAFF Allen S. Weller, Director Muriel B. Christlson, Associate Director Lois S. Frazee, Registrar Marie M. Cenkner, Graduate Assistant Kenneth C. Garber, Graduate Assistant Deborah A. Jones, Graduate Assistant Suzanne S. Stromberg, Graduate Assistant James O. Sowers, Preparator James L. Ducey, Assistant Preparator Mary B. DeLong, Secretary Tamasine L. Wiley, Secretary Catalogue and cover design: Raymond Perlman © 1969 by tha Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A48-340 Cloth: 252 00000 5 Paper: 252 00001 3 Acknowledgments h.r\ ^. f -r^Xo The College of Fine and Applied Arts and Esther-Robles Gallery, Los Angeles, Royal Marks Gallery, New York, New York California the Krannert Art Museum are grateful to Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., New those who have lent paintings and sculp- Fairweother Hardin Gallery, Chicago, York, New York ture to this exhibition and acknowledge Illinois Dr. Thomas A. Mathews, Washington, the of the artists, Richard Gallery, Illinois cooperation following Feigen Chicago, D.C. collectors, museums, and galleries: Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, Midtown Galleries, New York, New York New York ACA Golleries, New York, New York Mr. -

Selected Bibliography and Exhibition History

6/6/11 n11 Karlstrom_bib.doc: 163 Selected Bibliography and Exhibition History The following selected bibliography and exhibition history have been compiled by Jeff Gunderson, longtime librarian at the San Francisco Art Institute, the intended repository for the Peter Selz library. Gunderson worked closely with the author of this book, along with Selz himself, in setting up the guidelines for inclusion. For a full bibliography of articles, essays, books, and catalogues by Peter Selz, as well as a complete list of exhibitions for which he was curator, see www.ucpress.edu/go/peterselz. The lists presented here demonstrate Selz’s wide range of interests and expertise, as well as his advocacy for fine artists and his belief that art can be a fitting vehicle for social and political commentary. For the two bibliographic sections, “Books and Catalogues” and “Journal Articles and Essays,” the selection of titles was made on the basis of their significance and the contribution that they represent. Although Selz has been involved in and responsible for numerous exhibition-related publications, the extent of his involvement in these catalogues has varied widely. Those listed here (and indicated by an asterisk) are for the projects in which he took the lead authorial role, whatever his position in conceiving or producing the accompanying exhibition. Selz wrote a great number of magazine articles and reviews as well, many of them as West Coast correspondent for Art in America. With few exceptions, the regional exhibition reviews are not included. On the other hand, independent articles that represent the development and application of his thinking about modernist art are cited. -

Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) Is Published Monthly Except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S

William C. Hunt........................................ Editor Barbara Tipton...................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager........................ Art Director Ruth C. Butler.............................. Copy Editor Valentina Rojo....................... Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley............... Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.............................. Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S. L. Davis, Pres.; P. S. Emery, Sec.: 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year SI6, two years $30, three years $40. Add $5 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine wrapper label and your new address to Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Office, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, texts and news releases dealing with ceramic art are welcome and will be considered for publication. A booklet describing procedures for the preparation and submission of a man uscript is available upon request. Send man uscripts and correspondence about them to The Editor, Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Indexing:Articles in each issue of Ceramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index. A 20-year subject index (1953-1972) covering Ceramics Monthly feature articles, Sugges tions and Questions columns is available for $1.50, postpaid from the Ceramics Monthly Book Department, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Additionally, each year’s arti cles are indexed in the December issue. -

Nmservis Nceca 2015

nce lournal 'Volume37 lllllllIt { t t \ \ t lr tJ. I nceoqKAlt$[$ 5OthAnnual Conference of the NationalCouncilon C0'LECTURE:INNOVATIONS lN CALIFORNIACIAY NancyM. Servis and fohn Toki Introduction of urbanbuildings-first with architecturalterra cotta and then Manythink cerar.nichistory in theSan Francisco Bay Area with Art Decotile. beganin 1959with PeterVoulkos's appointrnent to theUniversi- California'sdiverse history served as the foundationfor ty of California-Berkeley;or with Funkartist, Robert Arneson, its unfolding cultural pluralisrn.Mexico claimed territory whosework at Universityof California-Davisredefined fine art throughlarge land grants given to retiredmilitary officersin rnores.Their transfonnative contributions stand, though the his- themid l9th century.Current cities and regions are namesakes tory requiresfurther inquiry. Califbr- of Spanishexplorers. Missionaries nia proffereda uniqueenvironr.nent arriving fronr Mexico broughtthe through geography,cultural influx, culture of adobe and Spanishtile and societalflair. cleatingopportu- with ther.n.Overland travelers rni- nity fbr experirnentationthat achieved gratedwest in pursuitof wealthand broadexpression in theceralnic arts. oppoltunity,including those warrtilrg Today,artistic clay use in Cali- to establishEuropean-style potteries. forniais extensive.lts modernhistory Workersfrorn China rnined and built beganwith the l9th centurydiscov- railroads,indicative of California's ery of largeclay deposits in the Cen- directconnection to PacificRirn cul- tral Valley, near Sacramento.This -

Oral History Interview with Louis Mueller, 2014 June 24-25

Oral history interview with Louis Mueller, 2014 June 24-25 Funding for this interview was provided by the Artists' Legacy Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Louis Mueller on June 24-25, 2014. The interview took place in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Archives of American Art's Viola Frey Oral History Project funded by the Artists' Legacy Foundation. Louis Mueller, Mija Riedel, and the Artists' Legacy Foundation have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets appended by initials. The reader should bear in mind they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Louis Mueller at the artist's home in New York [City] on June 24, 2014 for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Let's get the autobiographical information out of the way and we'll move on from there. LOUIS MUELLER: Okay. MS. RIEDEL: —what year were you born? MR. MUELLER: I was born June 15, 1943 in Paterson, NJ . MS. RIEDEL: And what were your parents' names? MR. MUELLER: My mother's name was Loretta. My father's name was Louis Paul. MS. RIEDEL: And your mother's maiden name? MR. MUELLER: Alfano. MS. RIEDEL: Any siblings? MR. MUELLER: No. -

Artwork by Viola Frey Gods & Monsters Artwork by Viola Frey

GODS & MONSTERS ARTWORK BY VIOLA FREY GODS & MONSTERS ARTWORK BY VIOLA FREY American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC Curated by Squeak Carnwath GODS & MONSTERS: The Early Work of Viola Frey By Mark Van Proyen Beginnings are delicate and hard to know, simply because there is always an earlier origin that pre-exists and bears upon any moment of presumed origination. As is the case with every artist’s career, this observation is borne out by the story of Viola Frey (1933–2004) as a painter and ceramic sculptor. Frey herself would say that she began her professional artistic career when she dug out the base- ment in her Divisadero home in San Francisco to house an art studio—four years after her return to California, and before that, four more years split between New Orleans and New York. But that beginning had its own complex pre-history reaching further back in time, and Frey’s pre-history is echoed and reflected in much of the work that she created up until her death in 2004, even after she suffered a series of debilitating strokes. Viola Frey, Ming Blue and White, 1981. Oil and acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 1/2 in. ALF no. VF-0327WP. Artists’ Legacy Foundation, Oakland, CA. Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree. 2 3 Frey was born in 1933 and grew up on a family-run grape farm in Lodi, an apartment at 495 Francisco Street, which was very close to the mediagenic heart of California. Following high school, she attended Stockton College, and the Beatnik subculture that had gained international attention after the controversial then went on to the California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) from reading of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl at the Six Gallery in late 1955.