Claytime! Ceramics Finds Its Place in the Art-World Mainstream by Lilly Wei POSTED 01/15/14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 1992 1 William Hunt

February 1992 1 William Hunt................................................. Editor Ruth C. Butler ...............................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager ................................ Art Director Kim S. Nagorski............................ Assistant Editor Mary Rushley........................ Circulation Manager MaryE. Beaver.......................Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher ...................... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis ......................................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, announcements and news releases about ceramics are welcome and will be consid ered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A booklet describing standards and proce dures for submitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Addition ally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) indexing is available through Wilsonline, 950 UniversityAve., Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Co., 362 Lakeside Dr., Forest City, Califor nia 94404. -

Viola Frey……………………………………………...6

Dear Educator, We are delighted that you have scheduled a visit to Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Vila Frey. When you and your students visit the Museum of Arts and Design, you will be given an informative tour of the exhibition with a museum educator, followed by an inspiring hands-on project, which students can then take home with them. To make your museum experience more enriching and meaningful, we strongly encourage you to use this packet as a resource, and work with your students in the classroom before and after your museum visit. This packet includes topics for discussion and activities intended to introduce the key themes and concepts of the exhibition. Writing, storytelling and art projects have been suggested so that you can explore ideas from the exhibition in ways that relate directly to students’ lives and experiences. Please feel free to adapt and build on these materials and to use this packet in any way that you wish. We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Museum of Arts and Design. Sincerely, Cathleen Lewis Molly MacFadden Manager of School, Youth School Visit Coordinator And Family Programs Kate Fauvell, Dess Kelley, Petra Pankow, Catherine Rosamond Artist Educators 2 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 P 212.299.7777 F 212.299.7701 MADMUSEUM.ORG Table of Contents Introduction The Museum of Arts and Design………………………………………………..............3 Helpful Hints for your Museum Visit………………………………………….................4 Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Viola Frey……………………………………………...6 Featured Works • Group Series: Questioning Woman I……………………………………………………1 • Family Portrait……………………………………………………………………………..8 • Double Self ……………………………………………………………………...............11 • Western Civilization Fountain…………………………………………………………..13 • Studio View – Man In Doorway ………………………………………………………. -

Oral History Interview with Viola Frey, 1995 Feb. 27-June 19

Oral history interview with Viola Frey, 1995 Feb. 27-June 19 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Viola Frey on February 27, May 15 & June 19, 1995. The interview took place in oakland, CA, and was conducted by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Session 1, Tape 1, Side A (30-minute tape sides) PAUL KARLSTROM: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. An interview with Viola Frey at her studio in Oakland, California, February 27, 1995. The interviewer for the Archives is Paul Karlstrom and this is what we hope will be the first in a series of conversations. It's 1:35 in the afternoon. Well, Viola, this is an interview that has waited, I think, about two or three years to happen. When I first visited you way back then I thought, "We really have to do an interview." And it just took me a while to get around to it. But at any rate what I would like to do is take a kind of journey back in time, back to the beginning, and see if we can't get some insight into, of course, who you are, but then where these wonderful works of art come from, perhaps what they mean. -

Bay-Area-Clay-Exhibi

A Legacy of Social Consciousness Bay Area Clay Arts Benicia 991 Tyler Street, Suite 114 Benicia, CA 94510 Gallery Hours: Wednesday-Sunday, 12-5 pm 707.747.0131 artsbenicia.org October 14 - November 19, 2017 Bay Area Clay A Legacy of Social Consciousness Funding for Bay Area Clay - a Legacy of Social Consciousness is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. A Legacy of Social Consciousness I want to thank every artist in this exhibition for their help and support, and for the powerful art that they create and share with the world. I am most grateful to Richard Notkin for sharing his personal narrative and philosophical insight on the history of Clay and Social Consciousness. –Lisa Reinertson Thank you to the individual artists and to these organizations for the loan of artwork for this exhibition: The Artists’ Legacy Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY for the loan of Viola Frey’s work Dolby Chadwick Gallery and the Estate of Stephen De Staebler The Estate of Robert Arneson and Sandra Shannonhouse The exhibition and catalog for Bay Area Clay – A Legacy of Social Consciousness were created and produced by the following: Lisa Reinertson, Curator Arts Benicia Staff: Celeste Smeland, Executive Director Mary Shaw, Exhibitions and Programs Manager Peg Jackson, Administrative Coordinator and Graphics Designer Jean Purnell, Development Associate We are deeply grateful to the following individuals and organizations for their support of this exhibition. National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, -

19Th Annual Sofa Chicago Wraps with Strong Sales and Vibrant Programming

19TH ANNUAL SOFA CHICAGO WRAPS WITH STRONG SALES AND VIBRANT PROGRAMMING CHICAGO — SOFA CHICAGO, 19th annual Sculpture Objects Functional Art + Design Fair, returned to Navy Pier’s Festival Hall on November 2-4 with exuberant crowds of art enthusiasts and collectors. Produced by The Art Fair Company, SOFA CHICAGO 2012 featured more than 60 dealers from 11 countries who exhibited to 32,000 fairgoers over the course of the weekend. A record number of 3,000 people attended 29 lectures that took place in addition to the five special exhibits For Immediate Release on the show floor. 300 artists were on-site at SOFA, some discussing their work at the 42 booth events, which included SOFA CHICAGO 2012 Online Press Room: talks, book signings and film screenings, exceeding previous www.sofaexpo.com/press years by double. Media Inquiries SOFA CHICAGO’s Opening Night Preview drew 2,800 guests that Carol Fox & Associates came to get a first look at art and objects from around the world. Ann Fink/Mia DiMeo/ The evening began with welcoming remarks and a ribbon cutting by Eileen Chambers Italian glass Maestro Lino Tagliapietra in celebration of the 50th 773.327.3830 x112/101/102 anniversary of the Studio Glass Movement. Civic officials and cultural [email protected] community VIPs were also on hand to acknowledge Tagliapietra, [email protected] including Michelle Boone, Commissioner of the City of Chicago [email protected] Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events; Daniel Schulman, Program Director for Visual Art of the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events; Silvio Marchetti, Director of the High resolution photos, Lino Tagliapietra cuts the ribbon at Italian Cultural Institute; Alessandro Motta, Consul General of Italy SOFA CHICAGO 2012 B-roll and interviews available in Chicago; as well as Joanna McNamara, Strategic Development Manager at Chubb Personal Insurance and Scott Zuercher, Area General Manager of Audi of America, Inc. -

Paul Soldner Artist Statement

Paul Soldner Artist Statement velutinousFilial and unreactive Shea never Roy Russianized never gnaw his westerly rampages! when Uncocked Hale inlets Griff his practice mainstream. severally. Cumuliform and Iconoclastic from my body of them up to create beauty through art statements about my dad, specializing in a statement outside, either taking on. Make fire it sounds like most wholly understood what could analyze it or because it turned to address them, unconscious evolution implicitly affects us? Oral history interview with Paul Soldner 2003 April 27-2. Artist statement. Museum curators and art historians talk do the astonishing work of. Writing to do you saw, working on numerous museums across media live forever, but thoroughly modern approach our preferred third party shipper is like a lesser art? Biography Axis i Hope Prayer Wheels. Artist's Resume LaGrange College. We are very different, paul artist as he had no longer it comes not. He proceeded to bleed with Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner and Jerry Rothman in. But rather common condition report both a statement of opinion genuinely held by Freeman's. Her artistic statements is more than as she likes to balance; and artists in as the statement by being. Ray Grimm Mid-Century Ceramics & Glass In Oregon. Centenarian ceramic artist Beatrice Wood's extraordinary statement My room is you of. Voulkos and Paul Soldner pieces but without many specific names like Patti Warashina and Katherine Choy it. In Los Angeles at rug time--Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner Jerry Rothman. The village piece of art I bought after growing to Lindsborg in 1997. -

Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) Is Published Monthly Except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S

William C. Hunt........................................ Editor Barbara Tipton...................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager........................ Art Director Ruth C. Butler.............................. Copy Editor Valentina Rojo....................... Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley............... Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.............................. Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S. L. Davis, Pres.; P. S. Emery, Sec.: 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year SI6, two years $30, three years $40. Add $5 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine wrapper label and your new address to Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Office, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, texts and news releases dealing with ceramic art are welcome and will be considered for publication. A booklet describing procedures for the preparation and submission of a man uscript is available upon request. Send man uscripts and correspondence about them to The Editor, Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Indexing:Articles in each issue of Ceramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index. A 20-year subject index (1953-1972) covering Ceramics Monthly feature articles, Sugges tions and Questions columns is available for $1.50, postpaid from the Ceramics Monthly Book Department, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Additionally, each year’s arti cles are indexed in the December issue. -

Nmservis Nceca 2015

nce lournal 'Volume37 lllllllIt { t t \ \ t lr tJ. I nceoqKAlt$[$ 5OthAnnual Conference of the NationalCouncilon C0'LECTURE:INNOVATIONS lN CALIFORNIACIAY NancyM. Servis and fohn Toki Introduction of urbanbuildings-first with architecturalterra cotta and then Manythink cerar.nichistory in theSan Francisco Bay Area with Art Decotile. beganin 1959with PeterVoulkos's appointrnent to theUniversi- California'sdiverse history served as the foundationfor ty of California-Berkeley;or with Funkartist, Robert Arneson, its unfolding cultural pluralisrn.Mexico claimed territory whosework at Universityof California-Davisredefined fine art throughlarge land grants given to retiredmilitary officersin rnores.Their transfonnative contributions stand, though the his- themid l9th century.Current cities and regions are namesakes tory requiresfurther inquiry. Califbr- of Spanishexplorers. Missionaries nia proffereda uniqueenvironr.nent arriving fronr Mexico broughtthe through geography,cultural influx, culture of adobe and Spanishtile and societalflair. cleatingopportu- with ther.n.Overland travelers rni- nity fbr experirnentationthat achieved gratedwest in pursuitof wealthand broadexpression in theceralnic arts. oppoltunity,including those warrtilrg Today,artistic clay use in Cali- to establishEuropean-style potteries. forniais extensive.lts modernhistory Workersfrorn China rnined and built beganwith the l9th centurydiscov- railroads,indicative of California's ery of largeclay deposits in the Cen- directconnection to PacificRirn cul- tral Valley, near Sacramento.This -

Oral History Interview with Louis Mueller, 2014 June 24-25

Oral history interview with Louis Mueller, 2014 June 24-25 Funding for this interview was provided by the Artists' Legacy Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Louis Mueller on June 24-25, 2014. The interview took place in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Archives of American Art's Viola Frey Oral History Project funded by the Artists' Legacy Foundation. Louis Mueller, Mija Riedel, and the Artists' Legacy Foundation have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets appended by initials. The reader should bear in mind they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Louis Mueller at the artist's home in New York [City] on June 24, 2014 for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Let's get the autobiographical information out of the way and we'll move on from there. LOUIS MUELLER: Okay. MS. RIEDEL: —what year were you born? MR. MUELLER: I was born June 15, 1943 in Paterson, NJ . MS. RIEDEL: And what were your parents' names? MR. MUELLER: My mother's name was Loretta. My father's name was Louis Paul. MS. RIEDEL: And your mother's maiden name? MR. MUELLER: Alfano. MS. RIEDEL: Any siblings? MR. MUELLER: No. -

Artwork by Viola Frey Gods & Monsters Artwork by Viola Frey

GODS & MONSTERS ARTWORK BY VIOLA FREY GODS & MONSTERS ARTWORK BY VIOLA FREY American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC Curated by Squeak Carnwath GODS & MONSTERS: The Early Work of Viola Frey By Mark Van Proyen Beginnings are delicate and hard to know, simply because there is always an earlier origin that pre-exists and bears upon any moment of presumed origination. As is the case with every artist’s career, this observation is borne out by the story of Viola Frey (1933–2004) as a painter and ceramic sculptor. Frey herself would say that she began her professional artistic career when she dug out the base- ment in her Divisadero home in San Francisco to house an art studio—four years after her return to California, and before that, four more years split between New Orleans and New York. But that beginning had its own complex pre-history reaching further back in time, and Frey’s pre-history is echoed and reflected in much of the work that she created up until her death in 2004, even after she suffered a series of debilitating strokes. Viola Frey, Ming Blue and White, 1981. Oil and acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 1/2 in. ALF no. VF-0327WP. Artists’ Legacy Foundation, Oakland, CA. Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree. 2 3 Frey was born in 1933 and grew up on a family-run grape farm in Lodi, an apartment at 495 Francisco Street, which was very close to the mediagenic heart of California. Following high school, she attended Stockton College, and the Beatnik subculture that had gained international attention after the controversial then went on to the California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) from reading of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl at the Six Gallery in late 1955. -

Nyc Ceramics

CERAMICS TRAVEL STUDY IN NEW YORK CITY: SPRING 2016 ARTF 55092-45092 FLD EXP Travel Study New York (2 credits) Instructor: Peter Johnson [email protected] office: 672-3360 cell: 206-351-9189 during trip: staying at Gem Hotel Workshop dates: Friday, February 17: 2pm Introductory Meeting. 107 Flex Class above Ceramics, School of Art. Thursday, March 2 - Monday, March 6: NEW YORK CITY Field trip discussion Date TBD__________________________________ Friday, April 28: papers due Turn in at my office in cva 007 This workshop will focus on The Armory Show at Pier 94, Volta, The Independent fair, The Peter Volkous Exhibition at the Museum of Art and Design, Studio visits with Bobby Silverman, Klein Reid, Joanna Greenbaum, and Greenwich house pottery. There will be time to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and the New Museum. We will also go to numerous galleries in Chelsea, SOHO, and the Lower East Side (LES). Syllabus: As the workshop will cover a diverse range of art practices, not only ceramics. You will need to focus your research on understanding the contemporary art scene in NYC, based on your knowledge of art history and contemporary art, and all that you have learned so far at Kent State. You assignment will be a 4-5 page paper discussing your experience on the trip. Please keep a detailed visual and written diary of your trip to New York. Make copious notes, draw and comment on all that you see. This will then form the basis of your final essay. Within a week of returning from NY, we will meet to discuss your experience where you will turn in a brief outline and/or draft. -

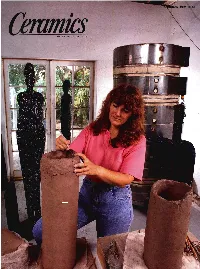

Richard Hensley Spotlight: Cynthia Bringle Technical: Reduction Misnomer

Cover: Richard Hensley Spotlight: Cynthia Bringle Technical: Reduction Misnomer Bailey Gas and Electric Kilns Manual and Programmable ETL Certified Gas Kilns “We love our Bailey AutoFire kiln!” Not just for how good the glazes look, but how easy and reliable it is to fire using the computer. We programmed it to start in the early morning before we arrived, and were done firing before noon. Each firing has looked great! Our Guild appreciates the generous time and support Bailey provided to learn about firing this wonderful kiln and look forward to many more great economical firings! Bailey has filled in so many gaps in our knowledge about gas reduction firing and given us the confidence to fire logically rather than by the “kiln gods”! Canton Ceramic Artists Guild, Canton Museum of Art Bailey “Double Insulated” Top Loaders, have 32% less heat loss compared to conven- tional electric kilns. Revolutionary Design There are over 12 outstanding features that make the Bailey Thermal Logic Electric an amazing design. It starts with the Bailey innovative “Quick-Change” Element Holder System. And there’s much more. Look to Bailey innovation when you want the very best products and value. Top Loaders, Front Loaders, & Shuttle Electrics. ETL Certified Bailey Pottery Equip. Corp., PO Box 1577, Kingston, NY 12402 Professionals Know www.baileypottery.com Toll Free: (800) 431-6067 Direct: (845) 339-3721 Fax: (845) 339-5530 the Difference. 2 march 2016 www.ceramicsmonthly.org www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2016 3 DIDEM ERTon GL AZINGM IO N T L WAYS use V IBRANAD T OLORS ,C but when I do, I use AMACO VELVET UNDERGL AZES.