IN the APPEALS CHAMBER Georges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Achievements and vital role of Tribunal .......................................................... 3 1.2 Strengthening the Tribunal .............................................................................. 4 1.3 Response of Tribunal officials ......................................................................... 7 1.4 Trials in the Rwandese Courts ......................................................................... 8 2. CREATION OF THE TRIBUNAL .............................................................................. 8 2.1 Statute of the Tribunal ................................................................................. 10 2.2 The first prosecutions .................................................................................... 12 3. DELAY OF TRIALS ................................................................................................... 12 4. PROSECUTION STRATEGY..................................................................................... 14 4.1 Relations with the Rwandese Government .................................................. 15 4.2 Prosecuting RPF abuses ................................................................................. 16 4.3 Investigation and prosecution of sexual violence crimes ............................... 17 5. WITNESS PROTECTION .......................................................................................... -

Hotel Rwanda - 1

Hotel Rwanda - 1 HOTEL RWANDA Hollywood and the Holocaust in Central Africa keith harmon snow Reprinting permitted with proper attribution to: <http://www.allthingspass.com> Text corrected, 1 November 2007 (see note [36-a]). What happened in Rwanda in 1994? The standard line is that a calculated genocide occurred because of deep-seated tribal animosity between the majority Hutu tribe in power and the minority Tutsis. According to this story, at least 500,000 and perhaps 1.2 million Tutsis—and some ‘moderate’ Hutus—were ruthlessly eliminated in a few months, and most of them were killed with machetes. The killers in this story were Hutu hard-liners from the Forces Armees Rwandais, the Hutu army, backed by the more ominous and inhuman civilian militias—the Interahamwe—“those who kill together.” “In three short, cruel months, between April and July 1994,” wrote genocide expert Samantha Power on the 10th anniversary of the genocide, “Rwanda experienced a genocide more efficient than that carried out by the Nazis in World War II. The killers were a varied bunch: drunk extremists chanting ‘Hutu power, Hutu power’; uniformed soldiers and militia men intent on wiping out the Tutsi Inyenzi, or ‘cockroaches’; ordinary villagers who had never themselves contemplated killing before but who decided to join the frenzy.” [1] The award-winning film Hotel Rwanda offers a Hollywood version and the latest depiction of this cataclysm. Is the film accurate? It is billed as a true story. Did genocide occur in Rwanda as it is widely portrayed and universally imagined? With thousands of Hutus fleeing Rwanda in 2005, in fear of the Tutsi government and its now operational village genocide courts, is another reading of events needed? [2] Hotel Rwanda - 2 Is Samantha Power—a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist—telling it straight? [3] Is it possible, as evidence confirms, that the now canonized United Nations peacekeeper Lt. -

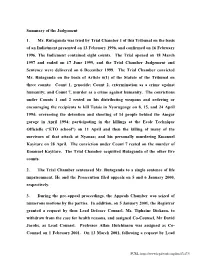

Summary of the Judgement 1. Mr. Rutaganda Was Tried by Trial

Summary of the Judgement 1. Mr. Rutaganda was tried by Trial Chamber I of this Tribunal on the basis of an Indictment presented on 13 February 1996, and confirmed on 16 February 1996. The Indicment contained eight counts. The Trial opened on 18 March 1997 and ended on 17 June 1999, and the Trial Chamber Judgement and Sentence were delivered on 6 December 1999. The Trial Chamber convicted Mr. Rutaganda on the basis of Article 6(1) of the Statute of the Tribunal on three counts: Count 1, genocide; Count 2, extermination as a crime against humanity; and Count 7, murder as a crime against humanity. The convictions under Counts 1 and 2 rested on his distributing weapons and ordering or encouraging the recipients to kill Tutsis in Nyarugenge on 8, 15, and 24 April 1994; overseeing the detention and shooting of 14 people behind the Amgar garage in April 1994; participating in the killings at the Ecole Technique Officielle (“ETO school”) on 11 April and then the killing of many of the survivors of that attack at Nyanza; and his personally murdering Emanuel Kayitare on 28 April. The conviction under Count 7 rested on the murder of Emanuel Kayitare. The Trial Chamber acquitted Rutaganda of the other five counts. 2. The Trial Chamber sentenced Mr. Rutaganda to a single sentence of life imprisonment. He and the Prosecution filed appeals on 5 and 6 January 2000, respectively. 3. During the pre-appeal proceedings, the Appeals Chamber was seized of numerous motions by the parties. In addition, on 5 January 2001, the Registrar granted a request by then Lead Defence Counsel, Ms. -

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: Bringing the Killers to Book

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda: bringing the killers to book by Chris Maina Peter No matter how many atrocities cases these international tri- bunals may eventually try, their very existence sends a powerful message. Their statutes, rules of procedure and evidence, and practice stimulate the development of the law.' In the spring of 1994 more than 500,000 people were killed in Rwanda in one of the worst cases of genocide in history. The slaughter began on 6 April 1994, only a few hours after the plane bringing the Presidents of Rwanda and Burundi back from peace negotiations in Tanzania was shot down as it approached Kigali Airport. It would seem that the genocide had been planned long in advance and that the only thing needed was the spark that would set it off. For months, Radio-Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTMC) had been spreading violent and racist propaganda on a daily basis fomenting hatred and urging its listeners to exterminate the Tutsis, whom it referred to as Inyenzi or "cockroaches".2 According to one source: The genocide had been planned and implemented with meticulous care. Working from prepared lists, an unknown and unknowable number of people, often armed with machetes, nail-studded clubs or Chris Maina Peter is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Dal- es Salaam. Tanzania. He is also Defence Counsel for indigent suspects and accused persons at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. 1 Theodor Meron, "The international criminalization of internal atrocities", American Journal of International Ixiw, Vol. 89, 1995, p. -

Forensic Turn

9 Bury or display? The politics of exhumation in post-genocide Rwanda Rémi Korman The practices and techniques employed by forensic anthropologists in the scientific documentation of human rights violations, and situ- ations of mass murder and genocide in particular, have developed enormously since the early 1990s.1 The best-known case studies con- cern Latin American countries which suffered under the dictator- ships of the 1970s–1980s, Franco’s Spain, and Bosnia. In Rwanda, the first forensic study of a large-scale massacre was carried out one year before the genocide, in January 1993, in the context of a report produced by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) on ‘the violations of human rights in Rwanda since 1 October’, the date marking the beginning of the country’s civil war.2 Although still comparatively little studied, this period constitutes a link between the pre- and post-genocide context. Since 1994, however, very few formal forensic investigations have in fact been carried out in Rwanda. Nevertheless, several thousand exhumations have been organized over the last twenty years by survivors of the genocide, churches, and the Rwandan state itself. What accounts for the specific features of the Rwandan case in this respect? In what context are these genocide exhumations carried out and who exactly are the actors organizing them in Rwanda? How are the mass graves to be located, opened, and selected, and how are the exhumed victims identified? The question of the role of foreign forensic anthropologists in Rwanda since the genocide is particularly important. While the role Rémi Korman - 9781526125019 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/23/2021 05:19:53PM via free access 204 Rémi Korman of foreign specialists in the memorialization and commemoration of the genocide is relatively well known, the activity of forensic anthro- pologists remains less thoroughly documented.3 Some of them came to Rwanda in the context of the criminal investigations carried out by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). -

Judgement and Sentence

UNITED NATIONS (~ NATION~cI~IES CRIH!.~ALREGISTRY RL :.~-I:VED InternationalCriminal Tribunal for R~u~. Tribunalp~nal international pour le Rw/thi~t~ -b A q: Sb TrialChamber I OR: FR. Before: JudgeLaity Kama, Presiding JudgeLennart Aspegren JudgeNavanethem Pillay Registrar: Mr. Agwu Okali Judgementof: 6 December1999 THE PROSECUTOR VERSUS GEORGES ANDERSON NDERUBUMWE RUTAGANDA Case No. ICTR-96-3-T JUDGEMENT AND SENTENCE TheOffice of theProsecutor: Ms.CarlaDel Ponte Mr.JamesStewart Mr.Udo HerbertGehring Ms.Holo Makwaia DefenceCounsel: Ms. TiphaineDickson UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES ~ InternationalCriminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunalp~nal international pourle Rwanda TrialChamber I THE PROSECUTOR VERSUS GEORGES ANDERSON NDERUBUMWE RUTAGANDA Case No. ICTR-96-3-T JUDGEMENT AND SENTENCE CaseNo: ICTR-96-3-T TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................... 3 1.1 The InternationalTribunal ........................................... 3 1.2. The Indictment................................................... 4 1.3 ProceduralBackground ............................................ 11 1.4 EvidentiaryMatters ............................................... 14 1.5 The Accused..................................................... 18 2 THE APPLICABLELAW ................................................20 2.1Individual Criminal Responsibility ................................... 20 2.2Genocide (Article 2 of the Statute)................................... 24 2.3.Crimes against Humanity (Article 3 of theStatute) ..................... -

• -Ii Iflaa 1 Tribunal Penal International Pour Le Rwanda U the Registrar Le Greffier P.O

07/14/98 THE 06:32 FAX 212 9634879 UNATIONS RIZA ilOOl 14/07 '98 11:38 FAX 212 963 2848 ICTR ARUSHA IQBAL RIZA USG ElOOl/004 iCTR COMMUNICATIONS CENTRE UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNITS!!! JUL DCTT'iVKn I u i A H: 31 ' International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda | *mH&m.' • -ii iflaa 1 Tribunal penal international pour le Rwanda U The Registrar Le Greffier P.O. Box 6016, Arnsha, Tanzania Tel: 255 57 4207-11/43*7-72 or 1 211963 2850 — Fai: 255 57 4000/4373 or I 212 9(S3 2S48 THANSMTSSTON — Ttt ATtfSMTSSTON PAR TF.T.F. Date: 13 July 1998 Ref: ICTR/RO/7/98/103 To: Mr. Iqbal Riza Prom: Agwu Uldwe Okali <i/\ — -^ Under-Secretary-General Assistant Secretarjj/^elieral Chef de Cabinet The Registrar f y Esocutivo Office of the Secretary-General United Nations TM>w Vnrk Fax No.: 212-963-4879 Reply Fax: 255-57-4373/4000 or 1-212-963-2848 Subject: ICTR arrests and transfers of genocide suspects and accused 1. Please find attached for your information a press release on a significant recent development in the work of the ICTR. 2. This operation, which has been planned and implemented by the Registay"and the Office of the Prosecutor, is indicative of the progress that the Tribunal is making in ajw spheres -judicial and administrative. 3. Best regards. Drafted by: Cleared by: No of transmitted pages including cover sheet: 07/14/98 TUE 06:32 [TX/RX NO 7990] g|001 07/14/98 TUB 06:33 FAX 212 9634879 UNATIONS ->-»^ RIZA J002 14/07 '98 11:38 FAX 212 963 2848 ICTR ARUSHA -» IQBAL RIZA ISG 0002/004 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda ? Tribunal p£ual international pour le Rwanda ppr* Press and Public Affairs Unit v-r Arasha luternaikmal Conference Centre P.O. -

Revisiting Hotel Rwanda: Genocide Ideology, Reconciliation, and Rescuers Lars Waldorf Version of Record First Published: 30 Apr 2009

This article was downloaded by: [United Nations] On: 19 April 2013, At: 07:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Genocide Research Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjgr20 Revisiting Hotel Rwanda: genocide ideology, reconciliation, and rescuers Lars Waldorf Version of record first published: 30 Apr 2009. To cite this article: Lars Waldorf (2009): Revisiting Hotel Rwanda: genocide ideology, reconciliation, and rescuers, Journal of Genocide Research, 11:1, 101-125 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14623520802703673 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Journal of Genocide Research (2009), 11(1), March, 101–125 Revisiting Hotel Rwanda: genocide ideology, reconciliation, and rescuers LARS WALDORF This article examines the tensions between the Rwandan government’s discourse on reconciliation and its fight against negationism. -

Paul Kagame a Sacrifié Les Tutsi

Amadou Deme Ex officier de renseignement de la MINUAR RWANDA 1994 ET L'ECHEC DES NATIONS UNIES TOUTE LA VERITE Le Nègre éditeur 2011 Glossaire: -AGR, RGF, FAR: Forces Rwandaises Gouvernementales selon que c'est en anglais ou français -RPF, FPR: Front Patriotique Rwandais GP: garde présidentielle -UNAMIR, MINUAR Mission d'Assistance des Nations Unies au Rwanda (ONU) -GOMN: Groupe d'Observateurs Militaires Neutres de l'OUA, soit une douzaine d'observateur et une compagnie d'infanterie légère tunisienne qui évoluait dans la zone démilitarisée, espace séparant les deux belligérants depuis 1991. Le GOMN a ensuite été absorbé par la MINUAR le 1er novembre 1993. -MONUOR: Mission des Nations Unies détachée de la MINUAR en Ouganda et censée surveiller les mouvements venant d'Ouganda vers le Rwanda. FC, CF Force Commander, commandant en chef de la Force des Nations Unies (Dallaire) -DOMP Département des Opérations de Maintien de la Paix aux Nations Unies (Direction de la MINUAR avec Koffi Annan) -RSSG: Représentant Spécial du Secrétaire Général des Nations Unies, Chef politique de la mission. Ce fut Jacques Roger Booh Booh, Camerounais, de nov 93 à juin 94 puis Sharyar M. Khan, Pakistanais à partir de juillet 94. Les sigles sont parfois en anglais, parfois anglais français, par exemple: RPF-FPR pour faciliter la compréhension. De même je mets entre parenthèses la traduction ou explicitation de certains termes pour les expliciter. LES SIGNES AVANT-COUREURS Le mois de mars était relativement calme, mais on voyait que des choses se préparaient. Une amie qui avait de bonnes relations avec le pouvoir et le FPR, et d'autres, mettaient leurs proches à l'abri à l'étranger...Au CND le FPR refusait que le CDR (parti extrémiste hutu) fasse partie des partenaires alors que ce dernier avait mis de l'eau dans son vin en acceptant de se contenter de sièges au parlement, et non au gouvernement. -

ENG TRIAL CHAMBER I11 Before: Judge I

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal penal international pour le Rwanda ~NlnONS NATIGNJVWES OR: ENG TRIAL CHAMBER I11 Before: Judge Inis M6nica Weinberg de Roca, presiding Judge Khalida Rachid Khan Judge Lee Gacuiga Muthoga Registrar: Adama Dieng Date: 18 December 2008 THE PROSECUTOR v. -- .- Protais ZIGIRANYIRAZO Case No. ZCTR-01-73-T JUDGEMENT Off~ceof the Prosecutor: Wallace Kapaya Charity Kagwi-Ndungu Gina Butler Iskandar Ismail Jane Mukangira Counsel for the Accused: John Philvot Peter ~aduk The Prosecutor v . Profais Zigiranyirnzo. Case No . ICTR-01-73-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 4 1. THE TRIBUNALAND ITS JURISDICTION ....................................................................4 2 . THE ACCUSED..................................................................................................... 4 3 . INDICTMENT...................................................................................................... 5 4 . SUMMARYOF PROCEDURALHISTORY ..................................................................... 5 5. OVERVIEWOF THE CASE........................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER 11: FACTUAL FINDINGS ....................................................................7 1. PRELIMINARYMATTERS ............................. .... ........................................................ 7 1. 1. Judicial Notice ............................................................................................ -

Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity

Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity A Digest of the Case Law of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-586-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org ii GENOCIDE, WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: A DIGEST OF THE CASE LAW OF THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................... iv DEDICATION ....................................................................................................... v FOREWORD ......................................................................................................... vi SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................... vii FULL TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................... ix SUMMARY OF JUDGMENTS AGAINST THE ACCUSED .............................. 1 LISTING OF CASES INCLUDED ..................................................................... 12 TOPICAL DIGEST ............................................................................................. -

RECEIVED 13 FEB 1996 ACTION: 12-~(4M-Cj Copy I PURL: the INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL for RWANDA

leT R . 56· .3 . , .\ 3 r~br'-'(<ly .-t 556 01 (4:;--13 ) UNITED NATIONS~) NATIONS UNIES ~ INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA CASE No: ICTR-96-3-1 THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST GEORGES ANDERSON NDERUBUMWE RUT AGANDA INDICTMENT 1 C T R RECEIVED 13 FEB 1996 ACTION: 12-~(4M-cJ copy I PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/aed81b/ THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA CASE NO: ICTR-96- 3· I THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST GEORGES ANDERSON NDERUBUMWE RUTAGANDA INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, pursuant to his authority under Article 17 of the Statute of the Tribunal charges: GEORGES ANDERSON NDERUBUMWE RUTAGANDA with GENOCIDE, CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY and VIOLATIONS OF ARTICLE 3 COMMON TO THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS, as set forth below: Background 1. On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying President Juvenal Habyarimana of Rwanda and President Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi crashed at Kigali airport, killing all on board. Following the deaths of the two Presidents, widespread killings, having both political and ethnic dimensions, began in Kigali and spread to other parts of Rwanda. PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/aed81b/ The Accused 2. Georges RUTAGANDA, born in 1958 in Masango commune, Gitarama prefecture, was an agricultural engineer and businessman; he was general manager and proprietor of Rutaganda SARL. Georges RUTAGANDA was also a member of the National and Prefectoral Committees of the Mouvement Republicain National pour Ie Developpement et la Democratie (hereinafter, "MRND") and a shareholder of Radio Television Libre des Mille eollines. On April 6, 1994, he was serving as the second vice president of the National Committee of the Interahamwe, the youth militia of the MRND.