Radionuclide Examination of Motility Disorders of the Esophagus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laparoscopic Heller's Cardiomyotomy in Cirrhosis with Oesophageal Varices

Unusual Case Laparoscopic Heller’s cardiomyotomy in cirrhosis with oesophageal varices Abhay N Dalvi, Pinky M Thapar, Nitin M Narawane1, Rippan N Shukla Departments of Minimal Invasive Surgery and 1Gastroenterology, Jupiter Hospital, Thane, Maharashtra, India. Address for correspondence: Dr. Abhay N Dalvi, 257 Walkeshwar Road, Mumbai-400 006, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract in the presence of varices is technically challenging. Bleeding obscuring the vision is one of the obstacles Surgical intervention in cirrhosis of liver with of this procedure that can lead to complication portal hypertension is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. This is attributed to of oesophageal mucosal perforation. Thorough liver decompensation, intra-operative bleeding, pre-operative investigations, planning, meticulous prolonged operative time, wound related and dissection are required to tackle this problem by a anaesthesia complications. Laparoscopic surgery laparoscopic approach. PUBMED search shows no in cirrhosis is advantageous but is associated with reported case of laparoscopic cardiomyotomy in patient technical challenges. We report one such case of cirrhosis with oesophageal varices. of hepatitis C cirrhosis with oesophageal varices and symptomatic achalasia cardia, who was successfully treated by laparoscopic cardiomyotomy CASE REPORT after thorough preoperative workup and planning. In the review of literature on pubmed, no such case A 53-year-old lady was referred to us for surgical is reported.. management of achalasia cardia. In the past, she had sustained severe gastroenteritis (30 years ago) for which Key words: Achalasia, cirrhosis, esophageal varices, laparoscopic cardiomyotomy. she was transfused 2 units of blood. She developed jaundice 25 years ago which responded to medical DOI: 10.4103/0972-9941.65164 management. -

Impairment of Nitric Oxide Pathway by Intravascular Hemolysis Plays A

1521-0103/367/2/194–202$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.118.249581 THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS J Pharmacol Exp Ther 367:194–202, November 2018 Copyright ª 2018 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Impairment of Nitric Oxide Pathway by Intravascular Hemolysis Plays a Major Role in Mice Esophageal Hypercontractility: Reversion by Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Stimulator Fabio Henrique Silva, Kleber Yotsumoto Fertrin, Eduardo Costa Alexandre, Fabiano Beraldi Calmasini, Carla Fernanda Franco-Penteado, and Fernando Ferreira Costa Hematology and Hemotherapy Center (F.H.S., K.Y.F., C.F.F.-P., F.F.C.) and Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Sciences (E.C.A., F.B.C.), University of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil; and Division of Hematology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington (K.Y.F.) Downloaded from Received April 1, 2018; accepted July 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) patients display cyclase stimulator 3-(4-amino-5-cyclopropylpyrimidin-2-yl)- exaggerated intravascular hemolysis and esophageal disor- 1-(2-fluorobenzyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine (BAY 41-2272; ders. Since excess hemoglobin in the plasma causes re- 1 mM) completely reversed the increased contractile responses jpet.aspetjournals.org duced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and oxidative stress, we to CCh, KCl, and EFS in PHZ mice, but responses remained hypothesized that esophageal contraction may be impaired unchanged with prior treatment with NO donor sodium nitro- by intravascular hemolysis. This study aimed to analyze the prusside (300 mM). Protein expression of 3-nitrotyrosine and alterations of the esophagus contractile mechanisms in a 4-hydroxynonenal increased in esophagi from PHZ mice, sug- murine model of exaggerated intravascular hemolysis induced gesting a state of oxidative stress. -

Chest Pain, Noncardiac

Sacramento Heart & Vascular Medical Associates February 18, 2012 500 University Ave. Sacramento, CA 95825 Page 1 916-830-2000 Fax: 916-830-2001 Patient Information For: Only A Test Chest Pain, Noncardiac What is noncardiac chest pain? Chest pain is discomfort that is located between the top of the belly and the base of the neck. Chest pain that is [not] caused by a heart problem is called noncardiac chest pain. Because it is very important to determine the cause, always see your healthcare provider if you have chest pain. How does it occur? The most worrisome causes of chest pain are related to your heart. However, many causes of chest pain are not related to a heart problem. These include: - swallowing disorders such as esophageal spasm, caused by the muscles of the lower esophagus squeezing painfully due to acid reflux or stress - gastrointestinal disorders such as heartburn, which is stomach acid backing up into the esophagus - lung disease such as bronchitis or pneumonia - problems affecting the ribs and chest muscles such as muscle strain or inflammation of the ribs or muscles - anxiety or panic attacks - inflammation of the sack around the heart (pericarditis) or of the lining of the lungs (pleuritis/pleurisy). How is it diagnosed? Keeping track of your chest pain will help your healthcare provider make the diagnosis. Write down: - what the pain feels like, such as stabbing, dull, or burning - when it happens and how long it lasts - where it hurts - what makes it better or worse - any other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, sweating, or trouble breathing. -

Diffuse Esophageal Spasm and Detrusor Spasm: Combined Visceral Neuromuscular Disorders in a Patient with William’S Syndrome

http://crim.sciedupress.com Case Reports in Internal Medicine, 2014, Vol. 1, No. 1 CASE REPORT Diffuse esophageal spasm and detrusor spasm: Combined visceral neuromuscular disorders in a patient with William’s Syndrome Jamie E. Ehrenpreis1, Gene Z. Chiao2, Eli D. Ehrenpreis3 1. Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, USA. 2. North Shore University Health System, Evanston, USA. 3. North Shore University Health System, Evanston, USA Correspondence: Eli D. Ehrenpreis, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine. Address: University of Chicago, Gastroente- rology Division, North Shore University Health System. Email: [email protected] Received: January 22, 2014 Accepted: February 18, 2014 Online Published: February 26, 2014 DOI: 10.5430/crim.v1n1p45 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/crim.v1n1p45 Abstract William’s Syndrome is a rare genetic disorder associated with developmental delay, gregarious personality, characteristic facies, multiple medical complications and valvular heart disease. Urologic and gastrointestinal complications including motor abnormalities and diverticulosis of the bladder and colon are commonly present. We present a case of a 37 year old male with William’s Syndrome who originally demonstrated typical bladder and bowel dysfunction associated with the condition, but also later developed severe dysphagia and associated weight loss. An esophagram revealed the presence of three large distal (epiphrenic) esophageal diverticula. These are most often caused by the presence of an underlying esophageal motility disorder. High-resolution esophageal manometry was performed and showed multiple simultaneous contractions and non-propagated contractions with swallowing maneuvers, consistent with the diagnosis of diffuse esophageal spasm (DES). This is the first case of an esophageal motor disorder described in a patient with William’s Syndrome and supports the concept that there is a generalized visceral neuromuscular dysfunction present in these patients. -

The Gastrointestinal System and the Elderly

2 The Gastrointestinal System and the Elderly Thomas W. Sheehy 2.1. Introduction Gastrointestinal diseases increase with age, and their clinical presenta tions are often confused by functional complaints and by pathophysio logic changes affecting the individual organs and the nervous system of the gastrointestinal tract. Hence, the statement that diseases of the aged are characterized by chronicity, duplicity, and multiplicity is most appro priate in regard to the gastrointestinal tract. Functional bowel distress represents the most common gastrointestinal disorder in the elderly. Indeed, over one-half of all their gastrointestinal complaints are of a functional nature. In view of the many stressful situations confronting elderly patients, such as loss of loved ones, the fears of helplessness, insolvency, ill health, and retirement, it is a marvel that more do not have functional complaints, become depressed, or overcompensate with alcohol. These, of course, make the diagnosis of organic complaints all the more difficult in the geriatric patient. In this chapter, we shall deal primarily with organic diseases afflicting the gastrointestinal tract of the elderly. To do otherwise would require the creation of a sizable textbook. THOMAS W. SHEEHY • Birmingham Veterans Administration Medical Center; and University of Alabama in Birmingham, School of Medicine, Birmingham, Alabama 35233. 63 S. R. Gambert (ed.), Contemporary Geriatric Medicine © Plenum Publishing Corporation 1988 64 THOMAS W. SHEEHY 2.1.1. Pathophysiologic Changes Age leads to general and specific changes in all the organs of the gastrointestinal tract'! Invariably, the teeth show evidence of wear, dis cloration, plaque, and caries. After age 70 years the majority of the elderly are edentulous, and this may lead to nutritional problems. -

Practical Approaches to Dysphagia Caused by Esophageal Motor Disorders Amindra S

Practical Approaches to Dysphagia Caused by Esophageal Motor Disorders Amindra S. Arora, MB BChir and Jeffrey L. Conklin, MD Address nonspecific esophageal motor disorders (NSMD), diffuse Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, esophageal spasm (DES), nutcracker esophagus (NE), 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA. hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter (hypertensive E-mail: [email protected] LES), and achalasia [1••,3,4••,5•,6]. Out of all of these Current Gastroenterology Reports 2001, 3:191–199 conditions, only achalasia can be recognized by endoscopy Current Science Inc. ISSN 1522-8037 Copyright © 2001 by Current Science Inc. or radiology. In addition, only achalasia has been shown to have an underlying distinct pathologic basis. Recent data suggest that disorders of esophageal motor Dysphagia is a common symptom with which patients function (including LES incompetence) affect nearly present. This review focuses primarily on the esophageal 20% of people aged 60 years or over [7••]. However, the motor disorders that result in dysphagia. Following a brief most clearly defined motility disorder to date is achalasia. description of the normal swallowing mechanisms and the Several studies reinforce the fact that achalasia is a rare messengers involved, more specific motor abnormalities condition [8•,9]. However, no population-based studies are discussed. The importance of achalasia, as the only exist concerning the prevalence of most esophageal motor pathophysiologically defined esophageal motor disorder, disorders, and most estimates are derived from people with is discussed in some detail, including recent developments symptoms of chest pain and dysphagia. A recent review of in pathogenesis and treatment options. Other esophageal the epidemiologic studies of achalasia suggests that the spastic disorders are described, with relevant manometric worldwide incidence of this condition is between 0.03 and tracings included. -

Adverse Events of Upper GI Endoscopy

GUIDELINE Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy This is one of a series of statements discussing the use of lications rely on self-reporting, and most reported data GI endoscopy in common clinical situations. The Stan- collected only from the immediate periprocedure period, dards of Practice Committee of the American Society for thus the rate of late adverse events and mortality may be Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) prepared this text. underestimated.8,9 Major adverse events related to diag- In preparing this document, a search of the medical liter- nostic UGI endoscopy are rare and include cardiopulmo- ature was performed by using PubMed. Additional refer- nary adverse events, infection, perforation, and bleeding. ences were obtained from the bibliographies of the identi- Adverse events of ERCP and EUS are discussed in separate fied articles and from recommendations of expert ASGE documents.10,11 consultants. When few or no data exist from well-designed prospective trials, emphasis is given to results of large series and reports from recognized experts. This document is ADVERSE EVENTS ASSOCIATED WITH based on a critical review of the available data and expert DIAGNOSTIC UGI ENDOSCOPY consensus at the time that the document was drafted. Further controlled clinical studies may be needed to clar- Cardiopulmonary adverse events ify aspects of this document. This document may be re- Most UGI procedures in the United States and Europe vised as necessary to account for changes in technology, are performed with patients under sedation (moderate or 12 new data, or other aspects of clinical practice. deep). Cardiopulmonary adverse events related to seda- This document is intended to be an educational device tion and analgesia account for as much as 60% of UGI 1-4,7 to provide information that may assist endoscopists in endoscopy adverse events. -

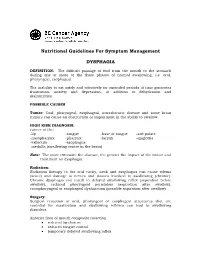

Nutritional Guidelines for Symptom Management DYSPHAGIA

Nutritional Guidelines For Symptom Management DYSPHAGIA DEFINITION: The difficult passage of food from the mouth to the stomach during one or more of the three phases of normal swallowing, i.e. oral, pharyngeal, esophageal. The inability to eat safely and effectively for extended periods of time generates frustration, anxiety and depression, in addition to dehydration and malnutrition. POSSIBLE CAUSES Tumor: Oral, pharyngeal, esophageal, intrathoracic disease and some brain tumors can cause an obstruction or impairment in the ability to swallow. HIGH RISK DIAGNOSIS: cancer of the: -lip -tongue -base of tongue -soft palate -nasopharynx -pharynx -larynx -epiglottis -vallecula -esophagus -medulla (swallowing centre in the brain) Note: The more extensive the disease, the greater the impact of the tumor and treatment on dysphagia. Radiation: Radiation therapy to the oral cavity, neck and esophagus can cause edema (acute) and damage to nerves and tissues involved in swallowing (chronic). Chronic dysphagia can result in delayed swallowing reflex (aspiration before swallow), reduced pharyngeal peristalsis (aspiration after swallow), cricopharyngeal or esophageal dysfunction (possible aspiration after swallow). Surgery: Surgical resection of oral, pharyngeal or esophageal structures that are essential for mastication and swallowing reflexes can lead to swallowing disorders. Anterior floor of mouth composite resection • reduced lip closure • reduced tongue control • temporary delayed swallowing reflex Tonsil/base of tongue composite resection • -

Dysphagia What Is Dysphagia? Dysphagia Is a General Term Used to Describe Difficulty Swallowing

Dysphagia What is Dysphagia? Dysphagia is a general term used to describe difficulty swallowing. While swallowing may seem very involuntary and basic, it’s actually a rather complex process involving many different muscles and nerves. Swallowing happens in 3 different phases: Insert Shutterstock ID: 119134822 1. During the first phase or oral phase the tongue moves food around in your mouth. Chewing breaks food down into smaller pieces, and saliva moistens food particles and starts to chemically break down our food. 2. During the pharyngeal phase your tongue pushes solids and liquids to the back of your mouth. This triggers a swallowing reflex that passes food through your throat (or pharynx). Your pharynx is the part of your throat behind your mouth and nasal cavity, it’s above your esophagus and larynx (or voice box). During this reflex, your larynx closes off so that food doesn’t get into your airways and lungs. 3. During the esophageal phase solids and liquids enter the esophagus, the muscular tube that carries food to your stomach via a series of wave-like muscular contractions called peristalsis. Insert Shutterstock ID: 1151090882 When the muscles and nerves that control swallowing don’t function properly or something is blocking your throat or esophagus, difficulty swallowing can occur. There are varying degrees of Dysphagia and not everyone will describe the same symptoms. Your symptoms will depend on your specific condition. Some people will experience difficulty swallowing only solids, or only dry solids like breads, while others will have problems swallowing both solids and liquids. Still others won’t be able to swallow anything at all. -

Dysphagia: Evaluation and Collaborative Management

Dysphagia: Evaluation and Collaborative Management John M. Wilkinson, MD; Don Chamil Codipilly, MD; and Robert P. Wilfahrt, MD Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minnesota Dysphagia is common but may be underreported. Specific symptoms, rather than their perceived location, should guide the initial evaluation and imaging. Obstructive symptoms that seem to originate in the throat or neck may actually be caused by distal esophageal lesions. Oropharyngeal dysphagia manifests as difficulty initiating swallowing, coughing, choking, or aspiration, and it is most commonly caused by chronic neurologic conditions such as stroke, Parkinson disease, or demen- tia. Symptoms should be thoroughly evaluated because of the risk of aspiration. Patients with esophageal dysphagia may report a sensation of food getting stuck after swallowing. This condition is most commonly caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional esophageal disorders. Eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by food allergens and is increasingly prevalent; esophageal biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. Esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia are relatively rare and may be overdiagnosed. Opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction is becoming more common. Esoph- agogastroduodenoscopy is recommended for the initial evaluation of esophageal dysphagia, with barium esophagography as an adjunct. Esophageal cancer and other serious conditions have a low prevalence, and testing in low-risk patients may be deferred while a four-week trial of acid-suppressing therapy is undertaken. Many frail older adults with progressive neuro- logic disease have significant but unrecognized dysphagia, which significantly increases their risk of aspiration pneumonia and malnourishment. In these patients, the diagnosis of dysphagia should prompt a discussion about goals of care before potentially harmful interventions are considered. -

The Gastrointestinal Tract Frank A

91731_ch13 12/8/06 8:55 PM Page 549 13 The Gastrointestinal Tract Frank A. Mitros Emanuel Rubin THE ESOPHAGUS Bezoars Anatomy THE SMALL INTESTINE Congenital Disorders Anatomy Tracheoesophageal Fistula Congenital Disorders Rings and Webs Atresia and Stenosis Esophageal Diverticula Duplications (Enteric Cysts) Motor Disorders Meckel Diverticulum Achalasia Malrotation Scleroderma Meconium Ileus Hiatal Hernia Infections of the Small Intestine Esophagitis Bacterial Diarrhea Reflux Esophagitis Viral Gastroenteritis Barrett Esophagus Intestinal Tuberculosis Eosinophilic Esophagitis Intestinal Fungi Infective Esophagitis Parasites Chemical Esophagitis Vascular Diseases of the Small Intestine Esophagitis of Systemic Illness Acute Intestinal Ischemia Iatrogenic Cancer of Esophagitis Chronic Intestinal Ischemia Esophageal Varices Malabsorption Lacerations and Perforations Luminal-Phase Malabsorption Neoplasms of the Esophagus Intestinal-Phase Malabsorption Benign tumors Laboratory Evaluation Carcinoma Lactase Deficiency Adenocarcinoma Celiac Disease THE STOMACH Whipple Disease Anatomy AbetalipoproteinemiaHypogammaglobulinemia Congenital Disorders Congenital Lymphangiectasia Pyloric Stenosis Tropical Sprue Diaphragmatic Hernia Radiation Enteritis Rare Abnormalities Mechanical Obstruction Gastritis Neoplasms Acute Hemorrhagic Gastritis Benign Tumors Chronic Gastritis Malignant Tumors MénétrierDisease Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis Peptic Ulcer Disease THE LARGE INTESTINE Benign Neoplasms Anatomy Stromal Tumors Congenital Disorders Epithelial Polyps -

Normal Gastrointestinal Motility and Function Esophagus

Normal Gastrointestinal Motility and Function "Motility" is an unfamiliar word to many people; it is used primarily to describe the contraction of the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract. Because the gastrointestinal tract is a circular tube, when these muscles contract, they close off the tube or make the opening inside smaller - they squeeze. These muscles can contract in a synchronized way to move the food in one direction (usually downstream, but occasionally upstream for short distances); this is called peristalsis. If you looked at the intestine, you would see a ring of contraction that moves along pushing contents ahead of it. At other times, the muscles in adjacent parts of the gastrointestinal tract squeeze more or less independently of each other: this has the effect of mixing the contents but not moving them up or down. Both kinds of contraction patterns are called motility. The gastrointestinal tract is divided into four distinct parts: the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine (colon). They are separated from each other by special muscles called sphincters which normally stay tightly closed and which regulate the movement of food and food residues from one part to another. Each part of the gastrointestinal tract has a unique function to perform in digestion, and as a result each part has a distinct type of motility and sensation. When motility or sensations are not appropriate for performing this function, they cause symptoms such as bloating, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea which are associated with subjective sensations such as pain, bloating, fullness, and urgency to have a bowel movement.