The Association of Reflux and Aspiration with NTM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impairment of Nitric Oxide Pathway by Intravascular Hemolysis Plays A

1521-0103/367/2/194–202$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.118.249581 THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS J Pharmacol Exp Ther 367:194–202, November 2018 Copyright ª 2018 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Impairment of Nitric Oxide Pathway by Intravascular Hemolysis Plays a Major Role in Mice Esophageal Hypercontractility: Reversion by Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Stimulator Fabio Henrique Silva, Kleber Yotsumoto Fertrin, Eduardo Costa Alexandre, Fabiano Beraldi Calmasini, Carla Fernanda Franco-Penteado, and Fernando Ferreira Costa Hematology and Hemotherapy Center (F.H.S., K.Y.F., C.F.F.-P., F.F.C.) and Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Sciences (E.C.A., F.B.C.), University of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil; and Division of Hematology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington (K.Y.F.) Downloaded from Received April 1, 2018; accepted July 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) patients display cyclase stimulator 3-(4-amino-5-cyclopropylpyrimidin-2-yl)- exaggerated intravascular hemolysis and esophageal disor- 1-(2-fluorobenzyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine (BAY 41-2272; ders. Since excess hemoglobin in the plasma causes re- 1 mM) completely reversed the increased contractile responses jpet.aspetjournals.org duced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and oxidative stress, we to CCh, KCl, and EFS in PHZ mice, but responses remained hypothesized that esophageal contraction may be impaired unchanged with prior treatment with NO donor sodium nitro- by intravascular hemolysis. This study aimed to analyze the prusside (300 mM). Protein expression of 3-nitrotyrosine and alterations of the esophagus contractile mechanisms in a 4-hydroxynonenal increased in esophagi from PHZ mice, sug- murine model of exaggerated intravascular hemolysis induced gesting a state of oxidative stress. -

Chest Pain, Noncardiac

Sacramento Heart & Vascular Medical Associates February 18, 2012 500 University Ave. Sacramento, CA 95825 Page 1 916-830-2000 Fax: 916-830-2001 Patient Information For: Only A Test Chest Pain, Noncardiac What is noncardiac chest pain? Chest pain is discomfort that is located between the top of the belly and the base of the neck. Chest pain that is [not] caused by a heart problem is called noncardiac chest pain. Because it is very important to determine the cause, always see your healthcare provider if you have chest pain. How does it occur? The most worrisome causes of chest pain are related to your heart. However, many causes of chest pain are not related to a heart problem. These include: - swallowing disorders such as esophageal spasm, caused by the muscles of the lower esophagus squeezing painfully due to acid reflux or stress - gastrointestinal disorders such as heartburn, which is stomach acid backing up into the esophagus - lung disease such as bronchitis or pneumonia - problems affecting the ribs and chest muscles such as muscle strain or inflammation of the ribs or muscles - anxiety or panic attacks - inflammation of the sack around the heart (pericarditis) or of the lining of the lungs (pleuritis/pleurisy). How is it diagnosed? Keeping track of your chest pain will help your healthcare provider make the diagnosis. Write down: - what the pain feels like, such as stabbing, dull, or burning - when it happens and how long it lasts - where it hurts - what makes it better or worse - any other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, sweating, or trouble breathing. -

The Gastrointestinal System and the Elderly

2 The Gastrointestinal System and the Elderly Thomas W. Sheehy 2.1. Introduction Gastrointestinal diseases increase with age, and their clinical presenta tions are often confused by functional complaints and by pathophysio logic changes affecting the individual organs and the nervous system of the gastrointestinal tract. Hence, the statement that diseases of the aged are characterized by chronicity, duplicity, and multiplicity is most appro priate in regard to the gastrointestinal tract. Functional bowel distress represents the most common gastrointestinal disorder in the elderly. Indeed, over one-half of all their gastrointestinal complaints are of a functional nature. In view of the many stressful situations confronting elderly patients, such as loss of loved ones, the fears of helplessness, insolvency, ill health, and retirement, it is a marvel that more do not have functional complaints, become depressed, or overcompensate with alcohol. These, of course, make the diagnosis of organic complaints all the more difficult in the geriatric patient. In this chapter, we shall deal primarily with organic diseases afflicting the gastrointestinal tract of the elderly. To do otherwise would require the creation of a sizable textbook. THOMAS W. SHEEHY • Birmingham Veterans Administration Medical Center; and University of Alabama in Birmingham, School of Medicine, Birmingham, Alabama 35233. 63 S. R. Gambert (ed.), Contemporary Geriatric Medicine © Plenum Publishing Corporation 1988 64 THOMAS W. SHEEHY 2.1.1. Pathophysiologic Changes Age leads to general and specific changes in all the organs of the gastrointestinal tract'! Invariably, the teeth show evidence of wear, dis cloration, plaque, and caries. After age 70 years the majority of the elderly are edentulous, and this may lead to nutritional problems. -

Practical Approaches to Dysphagia Caused by Esophageal Motor Disorders Amindra S

Practical Approaches to Dysphagia Caused by Esophageal Motor Disorders Amindra S. Arora, MB BChir and Jeffrey L. Conklin, MD Address nonspecific esophageal motor disorders (NSMD), diffuse Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, esophageal spasm (DES), nutcracker esophagus (NE), 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA. hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter (hypertensive E-mail: [email protected] LES), and achalasia [1••,3,4••,5•,6]. Out of all of these Current Gastroenterology Reports 2001, 3:191–199 conditions, only achalasia can be recognized by endoscopy Current Science Inc. ISSN 1522-8037 Copyright © 2001 by Current Science Inc. or radiology. In addition, only achalasia has been shown to have an underlying distinct pathologic basis. Recent data suggest that disorders of esophageal motor Dysphagia is a common symptom with which patients function (including LES incompetence) affect nearly present. This review focuses primarily on the esophageal 20% of people aged 60 years or over [7••]. However, the motor disorders that result in dysphagia. Following a brief most clearly defined motility disorder to date is achalasia. description of the normal swallowing mechanisms and the Several studies reinforce the fact that achalasia is a rare messengers involved, more specific motor abnormalities condition [8•,9]. However, no population-based studies are discussed. The importance of achalasia, as the only exist concerning the prevalence of most esophageal motor pathophysiologically defined esophageal motor disorder, disorders, and most estimates are derived from people with is discussed in some detail, including recent developments symptoms of chest pain and dysphagia. A recent review of in pathogenesis and treatment options. Other esophageal the epidemiologic studies of achalasia suggests that the spastic disorders are described, with relevant manometric worldwide incidence of this condition is between 0.03 and tracings included. -

Adverse Events of Upper GI Endoscopy

GUIDELINE Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy This is one of a series of statements discussing the use of lications rely on self-reporting, and most reported data GI endoscopy in common clinical situations. The Stan- collected only from the immediate periprocedure period, dards of Practice Committee of the American Society for thus the rate of late adverse events and mortality may be Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) prepared this text. underestimated.8,9 Major adverse events related to diag- In preparing this document, a search of the medical liter- nostic UGI endoscopy are rare and include cardiopulmo- ature was performed by using PubMed. Additional refer- nary adverse events, infection, perforation, and bleeding. ences were obtained from the bibliographies of the identi- Adverse events of ERCP and EUS are discussed in separate fied articles and from recommendations of expert ASGE documents.10,11 consultants. When few or no data exist from well-designed prospective trials, emphasis is given to results of large series and reports from recognized experts. This document is ADVERSE EVENTS ASSOCIATED WITH based on a critical review of the available data and expert DIAGNOSTIC UGI ENDOSCOPY consensus at the time that the document was drafted. Further controlled clinical studies may be needed to clar- Cardiopulmonary adverse events ify aspects of this document. This document may be re- Most UGI procedures in the United States and Europe vised as necessary to account for changes in technology, are performed with patients under sedation (moderate or 12 new data, or other aspects of clinical practice. deep). Cardiopulmonary adverse events related to seda- This document is intended to be an educational device tion and analgesia account for as much as 60% of UGI 1-4,7 to provide information that may assist endoscopists in endoscopy adverse events. -

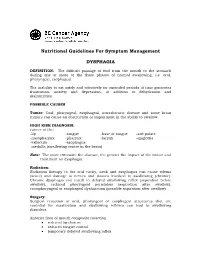

Nutritional Guidelines for Symptom Management DYSPHAGIA

Nutritional Guidelines For Symptom Management DYSPHAGIA DEFINITION: The difficult passage of food from the mouth to the stomach during one or more of the three phases of normal swallowing, i.e. oral, pharyngeal, esophageal. The inability to eat safely and effectively for extended periods of time generates frustration, anxiety and depression, in addition to dehydration and malnutrition. POSSIBLE CAUSES Tumor: Oral, pharyngeal, esophageal, intrathoracic disease and some brain tumors can cause an obstruction or impairment in the ability to swallow. HIGH RISK DIAGNOSIS: cancer of the: -lip -tongue -base of tongue -soft palate -nasopharynx -pharynx -larynx -epiglottis -vallecula -esophagus -medulla (swallowing centre in the brain) Note: The more extensive the disease, the greater the impact of the tumor and treatment on dysphagia. Radiation: Radiation therapy to the oral cavity, neck and esophagus can cause edema (acute) and damage to nerves and tissues involved in swallowing (chronic). Chronic dysphagia can result in delayed swallowing reflex (aspiration before swallow), reduced pharyngeal peristalsis (aspiration after swallow), cricopharyngeal or esophageal dysfunction (possible aspiration after swallow). Surgery: Surgical resection of oral, pharyngeal or esophageal structures that are essential for mastication and swallowing reflexes can lead to swallowing disorders. Anterior floor of mouth composite resection • reduced lip closure • reduced tongue control • temporary delayed swallowing reflex Tonsil/base of tongue composite resection • -

Dysphagia What Is Dysphagia? Dysphagia Is a General Term Used to Describe Difficulty Swallowing

Dysphagia What is Dysphagia? Dysphagia is a general term used to describe difficulty swallowing. While swallowing may seem very involuntary and basic, it’s actually a rather complex process involving many different muscles and nerves. Swallowing happens in 3 different phases: Insert Shutterstock ID: 119134822 1. During the first phase or oral phase the tongue moves food around in your mouth. Chewing breaks food down into smaller pieces, and saliva moistens food particles and starts to chemically break down our food. 2. During the pharyngeal phase your tongue pushes solids and liquids to the back of your mouth. This triggers a swallowing reflex that passes food through your throat (or pharynx). Your pharynx is the part of your throat behind your mouth and nasal cavity, it’s above your esophagus and larynx (or voice box). During this reflex, your larynx closes off so that food doesn’t get into your airways and lungs. 3. During the esophageal phase solids and liquids enter the esophagus, the muscular tube that carries food to your stomach via a series of wave-like muscular contractions called peristalsis. Insert Shutterstock ID: 1151090882 When the muscles and nerves that control swallowing don’t function properly or something is blocking your throat or esophagus, difficulty swallowing can occur. There are varying degrees of Dysphagia and not everyone will describe the same symptoms. Your symptoms will depend on your specific condition. Some people will experience difficulty swallowing only solids, or only dry solids like breads, while others will have problems swallowing both solids and liquids. Still others won’t be able to swallow anything at all. -

Dysphagia: Evaluation and Collaborative Management

Dysphagia: Evaluation and Collaborative Management John M. Wilkinson, MD; Don Chamil Codipilly, MD; and Robert P. Wilfahrt, MD Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minnesota Dysphagia is common but may be underreported. Specific symptoms, rather than their perceived location, should guide the initial evaluation and imaging. Obstructive symptoms that seem to originate in the throat or neck may actually be caused by distal esophageal lesions. Oropharyngeal dysphagia manifests as difficulty initiating swallowing, coughing, choking, or aspiration, and it is most commonly caused by chronic neurologic conditions such as stroke, Parkinson disease, or demen- tia. Symptoms should be thoroughly evaluated because of the risk of aspiration. Patients with esophageal dysphagia may report a sensation of food getting stuck after swallowing. This condition is most commonly caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional esophageal disorders. Eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by food allergens and is increasingly prevalent; esophageal biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. Esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia are relatively rare and may be overdiagnosed. Opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction is becoming more common. Esoph- agogastroduodenoscopy is recommended for the initial evaluation of esophageal dysphagia, with barium esophagography as an adjunct. Esophageal cancer and other serious conditions have a low prevalence, and testing in low-risk patients may be deferred while a four-week trial of acid-suppressing therapy is undertaken. Many frail older adults with progressive neuro- logic disease have significant but unrecognized dysphagia, which significantly increases their risk of aspiration pneumonia and malnourishment. In these patients, the diagnosis of dysphagia should prompt a discussion about goals of care before potentially harmful interventions are considered. -

Normal Gastrointestinal Motility and Function Esophagus

Normal Gastrointestinal Motility and Function "Motility" is an unfamiliar word to many people; it is used primarily to describe the contraction of the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract. Because the gastrointestinal tract is a circular tube, when these muscles contract, they close off the tube or make the opening inside smaller - they squeeze. These muscles can contract in a synchronized way to move the food in one direction (usually downstream, but occasionally upstream for short distances); this is called peristalsis. If you looked at the intestine, you would see a ring of contraction that moves along pushing contents ahead of it. At other times, the muscles in adjacent parts of the gastrointestinal tract squeeze more or less independently of each other: this has the effect of mixing the contents but not moving them up or down. Both kinds of contraction patterns are called motility. The gastrointestinal tract is divided into four distinct parts: the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine (colon). They are separated from each other by special muscles called sphincters which normally stay tightly closed and which regulate the movement of food and food residues from one part to another. Each part of the gastrointestinal tract has a unique function to perform in digestion, and as a result each part has a distinct type of motility and sensation. When motility or sensations are not appropriate for performing this function, they cause symptoms such as bloating, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea which are associated with subjective sensations such as pain, bloating, fullness, and urgency to have a bowel movement. -

The First-Bite Syndrome

Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal Volume 34 Number 4 Article 12 12-1986 The First-Bite Syndrome William S. Haubrich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Medical Specialties Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Haubrich, William S. (1986) "The First-Bite Syndrome," Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal : Vol. 34 : No. 4 , 275-278. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal/vol34/iss4/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal by an authorized editor of Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. The First-Bite Syndrome William S. Haubrich, MD^ Patients presenting with esophageal disorders often describe what can be called a "first-bite syndrome." The condition can be discerned by its characteristic clinical features. It may be a variant of diffuse esophageal spasm. While in a majority of patients it is a benign functional disturbance, it can be a harbinger of carcinoma. When of functional origin, it is amenable, in most cases, to relatively simple medical management. (Henry Ford Hosp MedJ 1986;34:275-8) syndrome is a concunence, in Greek literally "a mnning The survey included a review of symptoms, physical find A: Ltogether," of symptoms or signs that in a given patient ings, laboratory data, and the findings at radiography or endos come to indicate a particular abnormality. The more often one copy of the proximal alimentary tract. elicits from a series of patients a consistent set of symptoms, the The clinical criteria for identifying patients who exhibited the more convinced one becomes that the concunence is significant FBS were; 1) repeated episodes of dysphagia with retrostemal and not merely coincidence. -

EN GAST IND.Pdf

EN_GAST_IND.QXD 08/31/2005 11:31 AM Page 825 Index The bold letter t or f following a page reference indicates that the information appears on that page only in a table or figure, respectively. abdomen: examination of, 41–8; regions, 43f acetylcholine, 145, 190t abdominal aortic reconstruction, 275t acetyl-CoA, 53 abdominal mass: about, 37–40; with colon N-acetylcysteine, 582 cancer, 365t; and constipation, 386; with achalasia, 118f; about, 121–2; Crohn’s disease, 314, 342t; with cystic cricopharyngeal, 117t, 118; esophageal, fibrosis, 456; GI tract, 307, 373, 375, 379; 6–8, 14, 96, 118f, 120f; and gas, 14; and with hepatocellular carcinoma, 647; in Hirschsprung’s disease, 388; vigorous, pancreas, 434, 445; with ulcerative colitis, 121–2 342t achlorhydria, 57t, 217, 245t, 451 abetalipoproteinemia, 194, 201t acid perfusion test, 98, 106t abscesses: amebic, 392; anorectal, 397, 399, acid suppressants, 145 406–7; appendiceal, 320t; colonic, 391; acidosis: children, 687t, 689, 698, 715, 727t, crypt, 285, 331, 332f; diverticuler, 253; 729; cirrhosis, 571, 591; ischemia, 253, and diverticulitis, 373; eosinophilic, 114; 266; liver transplantation, 641; pancreatitis, horseshoe, 406; liver, 474; lung, 113; 433t; ulcerative colitis, 335 pancreatic, 434; pararectal, 316t; perianal, acids (chemicals), 115 344t acinar cells, 56, 418–19, 422 absorption: of carbohydrates, 194–9, 227–8; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. see in colon, 360, 362–4; of electrolytes, AIDS 185–92, 333; of fat, 192–4; of glucose, acrodermatitis enteropathica, 205t 194f; principles of, 178; of protein, actinomycosis, 149 199–202; of vitamins and minerals, acute abdomen, 24–7 178–83; of water, 183–5, 360 acute mesenteric ischemia, 252–4 acanthosis, glycogen, esophageal, 126t acyclovir, 294t, 301, 653 acanthosis nigricans, 126 acyclovir treatment, 114 ACE inhibitors. -

AGA Technical Review on the Clinical Use of Esophageal Manometry

GASTROENTEROLOGY 2005;128:209–224 AGA Technical Review on the Clinical Use of Esophageal Manometry This literature review and the recommendations therein were prepared for the American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee. The paper was approved by the Committee on October 2, 2004, and by the AGA Governing Board on November 7, 2004. he utility of esophageal manometry in clinical prac- function. In general, manometric data are only as valid as Ttice resides in 3 domains: (1) to accurately define the methodology used to acquire them. esophageal motor function, (2) to define abnormal motor The frequency content of esophageal contractile waves function, and (3) to delineate a treatment plan based on defines the required characteristics of a manometric re- motor abnormalities. Since the first American Gastroen- cording device. The frequency response required to re- terological Association technical review on esophageal produce esophageal pressure waves with 98% accuracy is manometry published 10 years ago,1,2 advances have 0–4 Hz, while that required for reproducing pharyngeal been made within each of these domains. By and large, pressure waves is 0–56 Hz.3 Expressed in terms of max- these advances have not been the result of major techno- imal recordable ⌬P/⌬t, 300 mm Hg/s will suffice for the logical changes but rather a reflection of improved man- mid or distal esophagus versus 4000 mm Hg/s for the ometric technique and research. With this in mind, the pharynx. Because the overall characteristics of the man- goal of this second technical review on the clinical use of ometric system are only as good as those of the weakest esophageal manometry is to summarize what has been element within that system, high-fidelity recordings re- learned during the past 10 years and discuss how this has quire that each element (pressure sensor, transducer, modified the clinical management of esophageal disor- recorder) meet or exceed these response characteristics.