The Guardian: Game of Editions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guardian News & Media

Response to Ofcom consultations on the BBC’s commercial activities and assessing the impact of the BBC’s public service activities About Guardian News & Media Guardian Media Group (GMG), a leading commercial media organisation, is the owner of Guardian News & Media (GNM) which publishes theguardian.com and the Guardian and Observer newspapers. Wholly owned by The Scott Trust Ltd, which exists to secure the financial and editorial independence of the Guardian in perpetuity, GMG is one of the few British-owned newspaper companies and is one of Britain's most successful global digital businesses, with operations in the USA and Australia and a rapidly growing audience around the world. As well as being a leading national quality newspapers, the Guardian and The Observer have championed a highly distinctive, open approach to publishing on the web and have sought global audience growth as a priority. A key consequence of this approach has been a huge growth in global readership, as theguardian.com has grown to become one of the world’s leading quality English language newspaper website in the world, with over 156 million monthly unique browsers. From its roots as a regional news brand, the Guardian now flies the flag for Britain and its media industry on the global stage. Introduction GMG is a strong supporter of the BBC, its core values of public service and its contribution to British public life. GMG supports the fundamentals of the BBC in its current form and a universal service funded through a universal levy, at least for the period covered by the next BBC Charter. -

Bias at the Beeb?

Pointmaker BIAS AT THE BEEB? A QUANTITATIVE STUDY OF SLANT IN BBC ONLINE REPORTING OLIVER LATHAM SUMMARY This paper uses objective, quantitative of coverage by the BBC than is coverage in methods, based on the existing academic The Daily Telegraph. literature on media bias, to look for evidence Once we control for coverage of a think-tank of slant in the BBC’s online reporting. in The Guardian, the number of hits a think- These methods minimise the need for tank received in The Daily Telegraph has no subjective judgements of the content of the statistically significant correlation with its BBC’s news output to be made. As such, they coverage by the BBC. are less susceptible to accusations of This paper then looks at the “health partiality on the part of the author than many warnings” given to think-tanks of different previous studies. ideological persuasions when they are The paper first examines 40 think-tanks mentioned on the BBC website. which the BBC cited online between 1 June It finds that right-of-centre think-tanks are far 2010 and 31 May 2013 and compares the more likely to receive health warnings than number of citations to those of The Guardian their left-of-centre counterparts (the former and The Daily Telegraph newspapers. received health warnings between 23% and In a statistical sense, the BBC cites these 61% of the time while the latter received think-tanks “more similarly” to that of The them between 0% and 12% of the time). Guardian than that of The Daily Telegraph. -

Managing Cancer-Related Fatigue

Managing cancer-related fatigue Cancer-related fatigue is the term used to describe extreme tiredness and is one of the most common, distressing and under-addressed symptoms in people living with or beyond a blood cancer. Cancer-related fatigue is not improved by rest and affects people physically, psychologically and socially; making it hard to complete normal everyday activities. It sometimes improves when treatment has finished but for some people it may last for months or years. Cancer-related fatigue can have many different causes including symptoms of the disease or side-effects of treatment. Some of these symptoms or side-effects may be linked together which can cause a cycle of fatigue. People with fatigue are often incorrectly advised to rest and limit activity. However, physical inactivity causes muscle weakness, increased stiffness and pain, and this may make fatigue worse. Fatigue is often linked to several physiological and psychological symptoms such as It is important to speak with your doctor to depression, anxiety, anaemia, weight loss find out which symptoms might be making and pain. These symptoms are linked to one your fatigue worse. Inside you will find some another and can make each other worse which practical tips for managing your fatigue. makes fatigue difficult to manage. leukaemia.org.nz 10 tips for managing fatigue 1) Keep a fatigue diary 4) Know your numbers a. Write down the times of day when you a. Anaemia is a common cause of fatigue feel your best and when you feel most so it is important to keep an eye on your tired. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee S4C Written evidence - web List of written evidence 1 URDD 3 2 Hugh Evans 5 3 Ron Jones 6 4 Dr Simon Brooks 14 5 The Writers Guild of Great Britain 18 6 Mabon ap Gwynfor 23 7 Welsh Language Board 28 8 Ofcom 34 9 Professor Thomas P O’Malley, Aberystwth University 60 10 Tinopolis 64 11 Institute of Welsh Affairs 69 12 NUJ Parliamentary Group 76 13 Plaim Cymru 77 14 Welsh Language Society 85 15 NUJ and Bectu 94 16 DCMS 98 17 PACT 103 18 TAC 113 19 BBC 126 20 Mercator Institute for Media, Languages and Culture 132 21 Mr S.G. Jones 138 22 Alun Ffred Jones AM, Welsh Assembly Government 139 23 Celebrating Our Language 144 24 Peter Edwards and Huw Walters 146 2 Written evidence submitted by Urdd Gobaith Cymru In the opinion of Urdd Gobaith Cymru, Wales’ largest children and young people’s organisation with 50,000 members under the age of 25: • The provision of good-quality Welsh language programmes is fundamental to establishing a linguistic context for those who speak Welsh and who wish to learn it. • It is vital that this is funded to the necessary level. • A good partnership already exists between S4C and the Urdd, but the Urdd would be happy to co-operate and work with S4C to identify further opportunities for collaboration to offer opportunities for children and young people, thus developing new audiences. • We believe that decisions about the development of S4C should be made in Wales. -

Press Freedom Under Attack

LEVESON’S ILLIBERAL LEGACY AUTHORS HELEN ANTHONY MIKE HARRIS BREAKING SASHY NATHAN PADRAIG REIDY NEWS FOREWORD BY PROFESSOR TIM LUCKHURST PRESS FREEDOM UNDER ATTACK , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY FOREWORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. WHY IS THE FREE PRESS IMPORTANT? 2. THE LEVESON INQUIRY, REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 A background to Leveson: previous inquiries and press complaints bodies 2.2 The Leveson Inquiry’s Limits • Skewed analysis • Participatory blind spots 2.3 Arbitration 2.4 Exemplary Damages 2.5 Police whistleblowers and press contact 2.6 Data Protection 2.7 Online Press 2.8 Public Interest 3. THE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK – A LEGAL ANALYSIS 3.1 A rushed and unconstitutional regime 3.2 The use of statute to regulate the press 3.3 The Royal Charter and the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 • The use of a Royal Charter • Reporting to Parliament • Arbitration • Apologies • Fines 3.4 The Crime and Courts Act 2013 • Freedom of expression • ‘Provided for by law’ • ‘Outrageous’ • ‘Relevant publisher’ • Exemplary damages and proportionality • Punitive costs and the chilling effect • Right to a fair trial • Right to not be discriminated against 3.5 The Press Recognition Panel 4. THE WIDER IMPACT 4.1 Self-regulation: the international norm 4.2 International response 4.3 The international impact on press freedom 5. RECOMMENDATIONS 6. CONCLUSION 3 , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY 4 , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY FOREWORD BY TIM LUCKHURST PRESS FREEDOM: RESTORING BRITAIN’S REPUTATION n January 2014 I felt honour bound to participate in a meeting, the very ‘Our liberty cannot existence of which left me saddened be guarded but by the and ashamed. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004

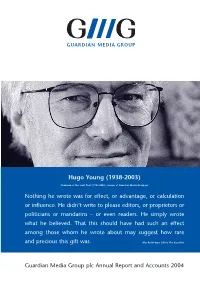

Hugo Young (1938-2003) Chairman of the Scott Trust (1989-2003), owners of Guardian Media Group plc Nothing he wrote was for effect, or advantage, or calculation or influence. He didn’t write to please editors, or proprietors or politicians or mandarins – or even readers. He simply wrote what he believed. That this should have had such an effect among those whom he wrote about may suggest how rare and precious this gift was. Alan Rusbridger, Editor, The Guardian Guardian Media Group plc Annual Report and Accounts 2004 1 Introduction Guardian Media Group plc is a UK media 2 Guardian Media Group plc structure 3 Chairman's statement business with interests in national newspapers, 6 Guardian Media Group plc Board of directors 8 Chief Executive’s review of operations community newspapers, magazines, radio 12 The Scott Trust 14 Corporate social responsibility 18 Financial review and internet businesses. The company is 20 Corporate governance 24 Report of the directors wholly-owned by the Scott Trust. 27 Independent auditors’ report 28 Group profit and loss account 29 Group balance sheet 30 Company balance sheet 31 Group statement of total recognised gains and losses The Scott Trust was created in 1936 to 32 Group cash flow statement 33 Cash flow reconciliations secure the financial and editorial 34 Notes relating to the 2004 financial statements 55 Group five year review independence of the Guardian in perpetuity. 56 Financial advisers Financial highlights 2004 73.5 67.3 634.8 62.1 43.6 526.0 456.4 47.4 36.9 439.0 437.4 29.4 29.8 9.8 1.6 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Turnover including share of Total group operating profit Profit before taxation. -

Media Education Journal – Autumn/Winter 2004/5 ‘Invisible Journalists’ by Jenny Mckay, University of Stirling [email protected]

Media Education Journal – Autumn/Winter 2004/5 ‘Invisible Journalists’ by Jenny McKay, University of Stirling [email protected] If you go into a newsagent to buy a magazine you’re likely to find around 450 titles to choose from. If you shop at one of the bigger supermarkets there might even be as many as 800. Yet this still represents only a small selection of the total number of magazines published in the UK. That figure is about 8,500 and can’t be precise because every year another 500 or so titles are launched. Some disappear too but the fact is that the UK has a large and lively periodicals industry publishing a huge range of titles to expanding audiences at home and abroad. These audiences tend to trust what they read in their magazines more than they trust their newspapers. Millions of magazines are sold weekly and almost everyone reads or buys one, or more likely several, at least on an occasional basis. This year saw the birth of two magazines which additionally represent the birth of a sector. Zoo and Nuts have found their young male readers and look set to thrive thanks, partly, to their multi-million pound launch budgets (£8.5m and £8m respectively) but also to the skill of their publishers in manipulating consumers into changing their behaviour. So now the UK has a men’s weekly magazine market that didn’t exist before, and that is ‘bursting with potential’ according to Sylvia Auton, chief executive of IPC Media which publishes Nuts. -

City Space and Urban Identity a Post-9/11 Consciousness in Australian Fiction 2005 to 2011

City Space and Urban Identity A Post-9/11 Consciousness in Australian Fiction 2005 to 2011 By Lydia Saleh Rofail A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 Declaration of Originality I affirm that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and I certify and warrant to the best of my knowledge that all sources of reference have been duly and fully acknowledged. Lydia Saleh Rofail i Abstract This thesis undertakes a detailed examination of a close corpus of five Australian literary novels published between 2005 and 2011, to assess the political, social, and cultural implications of 9/11 upon an urban Australian identity. My analysis of the literary city will reveal how this identity is trapped between layers of trauma which include haunting historical atrocities and inward nationalism, as well as the contrasting outward pull of global aspirations. Dead Europe by Christos Tsiolkas (2005), The Unknown Terrorist by Richard Flanagan (2006), Underground by Andrew McGahan (2006), Breath by Tim Winton (2008), and Five Bells by Gail Jones (2011) are uniquely varied narratives written in the shadow of 9/11. These novels reconfigure fictional notions of Australian urbanism in order to deal with fears and threats posed by 9/11 and the fallout that followed, where global interests fed into national concerns and discourses within Australia and resonated down to local levels. Adopting an Australia perspective, this thesis contextualises subsequent traumatic and apocalyptic trajectories in relation to urbanism and Australian identity in a post-9/11 world. -

Community Credit in Here Children’S Drawings on Display at the Big Draw Event at the Newsroom

Community credit in here Children’s drawings on display at the Big Draw event at the Newsroom. Photograph: David Levene 40 Living our values It is not only in our editorial coverage that we have an influence over people’s lives. As a company with around 1,500 employees and an ability to tap into a wealth of resources, we are also having a direct impact on the communities we serve. This includes support for schools and journalism projects across the world, as well as HIV projects in Africa The common good The Scott Trust Foundation The range of community activities has become Guardian’s training scheme for young journal- and the War on Terror. One-off workshops also so numerous that we have spent the last year ists in South Africa, the Foundation has run in conjunction with the Newsroom’s rolling putting a more strategic focus on what we do. developed partnerships in some new countries. programme of exhibitions. This has resulted in the creation of the Scott For example, it went to Ukraine to run a sem- The adjoining archive preserves the heritage Trust Foundation, an umbrella organisation for inar on the art of reporting the EU, and invited of our papers and enables others to share our all the activities taking place under the direc- a group of dynamic young Albanians to London history. Researchers can access material rang- tion of our owner, the Scott Trust. to find out about the mechanics of setting up ing from correspondence and photographs to The Scott Trust Foundation’s central remit re- their own newspaper. -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 14 June 2019) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £795 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

Early Development of News Sites in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1990S: Exploring Trans-Atlantic Connections

Will T. Mari Early Development of News Sites in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1990s: Exploring Trans-Atlantic Connections Abstract The many close, trans-Atlantic connections between the United States and Britain were the setting and inspiration for much of how these nations’ respective media systems produce and consume news online today. Publishers, soft- ware engineers and journalists in both nations shared worries about the impact of the internet on the newspaper industry, and the early migration—or, in many cases, the uneven migration—to online news sites during the 1990s. This paper will explore some of those shared concerns, down to the editor and reporter level, with a special focus on the mid-to-late 1990s, and concluding with what changed by the end of that decade, and what did not. It is part of a larger study examining the internet and journalism’s initial encounters. It is based on a close reading of trade publications, memoirs, oral-history interviews and other primary-source material, and inspired by the work of Niels Brügger, with its treatment of ‘web history’ in a serious and contextualized way. Keywords internet history, media history, history of online news, transnational media history In 2020, looking back at how journalism looked online in the 1990s, with its slow, buzzing dial up, simplistic graphics made of low-resolution photos (if they were posted at all) and lack of streaming, it might be hard to see the connection to the present, with its TikTok, immersive apps and omnipresent (more or less) Wi-Fi.