Feasibility of Using Alternative Water Sources for Shale Gas Well Completions — Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GSA Poster 2013 Long

Hydrological and Geochemical Characteristics in the Edwards and Trinity Hydrostratigraphic Units Using Multiport Monitor Wells in the Balcones Fault Zone, Hays County, Central Texas Alan Andrews, Brian Hunt, Brian Smith Purpose Rising-falling K Slug-in K Slug-out K Zone Zone (ft/day) (ft/day) (ft/day) Thickness (ft) Trans ft2/day Stratigraphy 21 0.3 -- -- 35 10 Stratigraphy General Hydrologic ID To better understand the hydrogeological properties of and 20 53 -- -- 70 3700 Eagle Ford/ Hydrostratigraphy Function thickness in feet Lithology Porosity/Permeability Sources Rising-falling K Slug K Zone Transmissivity Qal? confining Zone (ft/day) (ft/day) Thickness (ft) (ft2/day) 19 5 8 6 30 140 40-50 Dense limestone Buda unit (CU) Low 18 3 3 -- 25 84 relationships between the geologic units that make up the Confining Units 14 -- -- 136 -- CU Blue-green to 17 38 -- 44 105 4000 Upper Del Rio 50-60 Upper Confining Unit 13 65 -- 72 13000 137.9’ Fract oyster wakestone yellow-brown clay 16 29 80 19 70 2000 12 2 -- 34 460 145.7’ stylolites and fract I Edwards, Upper and Middle Trinity Aquifers and to compare Georgetown Fm. CU Marly limestone; grnst Low 15 29 105 161 75 2100 40-60 11 4 -- 159 8300 Crystalline limestone; mdst to wkst 14 8 10 3 45 370 Leached and 199.6’ fossil (toucasid) vug Aquifer (AQ) III to milliolid grnst; chert; collapse High 10 0.09 -- 197 50 13 4 2 6 40 160 observed hydrologic properties of formations to generally accept- Collapsed mbrs 230’ solutioned bedding plane 30-80 breccia 9 0.005 -- 97 4 12 0.2 -- -- 85 -- 200 feet Reg. -

A Juvenile Skeleton of the Nectridean Amphibian

Lucas, S.G. and Zeigler, K.E., eds., 2005, The Nonmarine Permian, New Mexico Museum of Natural Histoiy and Science Bulletin No. 30. 39 A JUVENILE SKELETON OF THE NECTRIDEAN AMPHIBIAN DIPLOCAULUS AND ASSOCIATED FLORA AND FAUNA FROM THE MITCHELL CREEK FLATS LOCALITY (UPPER WAGGONER RANCH FORMATION; EARLY PERMIAN), BAYLOR COUNTY, NORTH- CENTRAL TEXAS, USA DAN S. CHANEY, HANS-DIETER SUES AND WILLIAM A. DIMICHELE Department of Paleobiology MRC-121, National Museum of Natural History, PC Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7021 Abstract—A well-preserved skeleton of a tiny individual of the nectridean amphibian Diplocaulus was found in association with other Early Permian animal remains and a flora in a gray mudstone at a site called Mitchell Creek Flats in Baylor County, north-central Texas. The locality has the sedimentological attributes of a pond deposit. The skeleton of Diplocaulus sp. is noteworthy for its completeness and small size, and appears to represent a juvenile individual. The associated plant material is beautifully preserved and comprises the sphe- nopsids Annularia and Calamites, the conifer IBrachyphyllum, possible cycads represented by one or possibly two forms of Taeniopteris, three gigantopterids - Delnortea, Cathaysiopteris, and Gigantopteridium — and three unidentified callipterids. Several unidentified narrow trunks were found at the base of the deposit, appar- ently washed up against the northern margin of the pond. Other faunal material from the deposit comprises myalinid bivalves, conchostracans, a tooth of a xenacanthid shark, and a palaeonisciform fish. INTRODUCTION Wchita Rver T ^ Coinage i ^ 1 t Complete skeletons of Early Permian vertebrates are rare in north- FwmatJon Grcyp c central Texas, where much collecting has been done for about 150 years c c (Fig. -

New England Zoological Club

PROCEEDINGS OF THE NEW ENGLAND ZOOLOGICAL CLUB NEW GENERA AND SPECIES OF PELYCOSAURIAN REPTILES BY ALFRED SHERWOOD ROMER IN the course of recent collecting trips by the Museum of Comparative Zoology and a re-study of pre-existing collections, Ii number of new types of Permo-Carboniferous pelycosaurs have come to light. I hope to discuss these reptiles in a general review of the group, which is approaching completion. This $tudy has been aided by a grant from the Penrose Fund of the Geological Society of America, and the present preliminary cliagnoses of the new types are published with the permission or the Society. Eothyris parkeyi gen. et spec. nov. Genoholotype, M.C.Z., 1161, (figured): a skull and jaws, found about one mile west of the former Woodrum ranch-house, $outh of Dundee, Archer County, Texas; horizon Belle Plains P.N.E.Z.C. ROMER--PELYCOSAURS [ pooember30] 90 Vol. XVI 1937 ROMER--PELYCOSA Formation, Wichita Group. A small primitive pelycosaur, the type skull about 65 mm. in length as preserved. The skull Lupeosaurus kayi gen. et sp' is relatively broad and low, and the face short, (although this appearance is increased by distortion and damage in the type); Genoholotype, M.C.Z., 1455, a preS8 the orbit and temporal region are relatively elongated. The and scapulocoracoid, found near the postorbital has a broad posterior expansion above the small Creek, Archer County, Texas; horizOI temporal vacuity. The parietal is very primitive, in extend Formation, Wichita Group. A pelycos ing far back of the pineal. The supra-temporal is relatively sembling Edaphosaurus in caudal verter large. -

Xenacanthus (Chondrichthyes: Xenacanthiformes) from North America

Acta Geologica Polonica, Vol. 49 (J 999), No.3, pp. 215-266 406 IU S UNES 0 I Dentitions of Late Palaeozoic Orthacanthus species and new species of ?Xenacanthus (Chondrichthyes: Xenacanthiformes) from North America GARY D. JOHNSON Department of Earth Sciences and Physics, University of South Dakota; 414 East Clark Street, Vermillion, SD 57069-2390, USA. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: JOHNSON, G.D. 1999. Dentitions of Late Palaeozoic Orthacanthus species and new species of ?Xenacanthus (Chondrichthyes: Xenacanthiformes) from North America. Acta Geologica Polonica, 49 (3),215-266. Warszawa. Orthacanthus lateral teeth have paired, variably divergent, smooth, usually carinated labio-lingually compressed principal cusps separated by a central foramen; one or more intermediate cusps; and an api cal button on the base isolated from the cusps. Several thousand isolated teeth from Texas Artinskian bulk samples are used to define the heterodont dentitions of O. texensis and O. platypternus. The O. tex ensis tooth base has a labio-Iingual width greater than the anteromedial-posterolateral length, the basal tubercle is restricted to the thick labial margin, the principal cusps are serrated to varying degrees, and the posterior cusp is larger. The O. platypternus tooth base is longer than wide, its basal tubercle extends to the center, the labial margin is thin, serrations are absent on the principal cusps, the anterior cusp is larger, and a single intermediate cusp is present. More than two hundred isolated teeth from Nebraska (Gzhelian) and Pennsylvania (Asselian) provide a preliminary description of the heterodont dentition of O. compress us . The principal cusps are similar to O. -

Geology of the Cross Plains Quadrangle, Brown, Callahan Coleman, and Eastland Counties Texas

Geology of the Cross Plains Quadrangle, Brown, Callahan Coleman, and Eastland Counties Texas GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1096-B Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Economic Geology, The University of Texas Geology of the Cross Plains Quadrangle, Brown, Callahan Coleman, and Eastland Counties Texas By PHILIP T. STAFFORD PENNSYLVANIAN AND LOWER PERMIAN STRATIG RAPHY, BETWEEN THE BRAZOS AND COLORADO RIVERS, NORTH-CENTRAL TEXAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1096-B Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Economic Geology, The University of Texas UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.G. CONTENTS Page Abstract___ _____________________________________________________ 39 Introduction._____________________________________________________ 40 Location of area_______________________________________________ 40 Purpose ______________________________________________________ 40 Previous geologic studies. ______________________________________ 40 Acknowledgments _____________________________________________ 41 Methods of study____________________________________________ 42 Mapping and fieldwork___________________________________ 42 Descriptive terminology.__-____________-_____-___-_-_-_-___ 43 Stratigraphy. _____________________________________________________ 44 Pennsylvanian and Permian systems.____________________________ -

GEOLOGIC QUADRANGLE MAP NO. 49 Geology of the Pedernales Falls Quadrangle, Blanco County, Texas

BUREAU OF ECONOMIC GEOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN AUSTIN, TEXAS 78712 W. L. FISHER, Director GEOLOGIC QUADRANGLE MAP NO. 49 Geology of the Pedernales Falls Quadrangle, Blanco County, Texas By VIRGIL E. BARNES November 1982 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN TO ACCOMPANY MAP-GEOLOGIC BUREAU OF ECONOMIC GEOLOGY QUADRANGLE MAP NO. 49 GEOLOGY OF THE PEDERNALES FALLS QUADRANGLE, BLANCO COUNTY, TEXAS Virgil E. Barnes 1982 CONTENTS General setting .. .. .. ............... 2 Cretaceous System (Lower Cretaceous) . 10 Geologic formations ......... .. ... 2 Trinity Group . 10 Paleozoic rocks ........... .. .. 2 Travis Peak Formation . 10 Cambrian System (Upper Cambrian) . 2 Sycamore Sand . 10 Moore Hollow Group ....... 2 Hammett Shale and Cow Creek Wilberns Formation . ........ 2 Limestone . 10 San Saba Member . .. .... 2 Shingle Hills Formation . 10 Ordovician System (Lower Ordovician) .. 3 Hensen Sand Member . 10 Ellenburger Group . ... .. .... 3 Glen Rose Limestone Member . 10 Tanyard Formation .. ... .... 3 Cenozoic rocks . 11 Threadgill Member ..... ... 3 Quaternary System . 11 Staendebach Member ....... 3 Pleistocene Series . 11 Gorman Formation ...... 4 Terrace deposits . 11 Honeycut Formation ......... 5 Recent Series . 11 Devonian system . .. .... .... 7 Alluvium . 11 Stribling Formation .... .. .. 7 Subsurface geology . 11 Devonian-Mississippian rocks . ...... 8 Mineral resources . 12 Joint fillings ...... ... ... 8 Construction materials . 12 Houy Formation ....... .. .. 8 Building stone . 12 Mississippian System ......... ... -

30-Johnson (Xenacanth)

Lucas, S.G., et al. eds., 2013, The Carboniferous-Permian Transition. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 60. 161 XENACANTH SHARKS AND OTHER VERTEBRATES FROM THE GERALDINE BONEBED, LOWER PERMIAN OF TEXAS GARY D. JOHNSON Shuler Museum of Paleontology, Institute for the Study of Earth and Man, Southern Methodist University, PO Box 750274, Dallas, Texas 75275-0274; email: [email protected] Abstract—The Geraldine Bonebed occurs in the Nocona Formation (Wichita Group, Sakmarian age) in Texas. It has historically yielded a large number of mostly complete skeletons of four tetrapod taxa, for which it is famous, and also a diverse flora as well as other vertebrates. Bulk samples of matrix were recently screen-washed and sorted to produce a variety of vertebrate microfossils, including sharks, especially xenacanths. The non-xenacanth sharks are rare and include a petalodont tooth (Janassa?), Helodus sp. (4 teeth) and one partial hybodont tooth. These are all considerably more common higher in the Wichita Group. Only the petalodont and possibly the hybodont and Helodus represent a marine component in the fauna, but the marine faunas are more extensive higher in the Wichita. Also new to the fauna are acanthodians, actinopterygians, Cardiocephalus and Ophiacodon. Among the xenacanths are two typically small Xenacanthus sp. occipital spine fragments, two Orthacanthus sp. occipital spine frag- ments (one small, one very small) and hundreds of Orthacanthus teeth. Orthacanthus texensis teeth are much more common than O. platypternus teeth. Teeth of O. texensis and O. platypternus are comparable in size distributions, as determined by statistical analyses of the tooth-base measurements, to those higher in the Wichita Group. -

Occurrence, Availability, and Chemical Quality of Ground

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES REPORT 269 OCCURRENCE, AVAILABILITY, AND CHEMICAL QUALITY OF GROUND WATER IN THE CRETACEOUS AQUIFERS OF NORTH-CENTRAL TEXAS VOLUME 1 Phillip L. Nordstrom, Geologist April 1982 TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES Harvey Davis, Executive Director TEXAS WATER DEVELOPMENT BOARD Louis A. Beecherl Jr., Chairman John H. Garrett, Vice Chairman George W. McCleskey W. 0. Bankston Glen E. Roney Lonnie A. “Bo” Pilgrim TEXAS WATER COMMISSION Felix McDonald, Chairman Dorsey B. Hardeman, Commissioner Lee B. M. Biggart, Commissioner Authorization for use or reproduction of any original material contained in this publication, i.e., not obtained from other sources, is freely granted. The Department would appreciate acknowledgement. Published and distributed by the Texas Department of Water Resources Post Office Box 13087 Austin, Texas 78711 ii __ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS . 1 INTRODUCTION . .. 3 Purpose and Scope . 3 Location and Extent . 3 Physiography . 3 Climate . 4 Population . 4 Economy . 4 Previous Investigations . 4 Acknowledgements . 7 Method of Investigation . 7 Well-Numbering System . 7 Metric Conversion . 8 GEOLOGY AS RELATED TO THE OCCURRENCE OF GROUND WATER . 9 Geologic History . 9 Paleozoic . 9 Cretaceous . 9 Tertiary and Quaternary . 9 General Stratigraphy . 9 Structure . 10 STRATIGRAPHY OF THE WATER-BEARING FORMATIONS . 12 Paleozoic Rocks . 12 Antlers . 13 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS – Continued Page Twin Mountain Formation . 13 Paluxy Formation . 14 Woodbine Group . 14 Blossom Sand . 15 Nacatoch Sand . 15 CHEMICAL QUALITY OF GROUND WATER AS RELATED TO USE . 15 General Chemical Quality of Ground Water . 15 Quality Criteria or Standards . 16 Municipal . 16 Primary Standards . 20 Secondary Standards . -

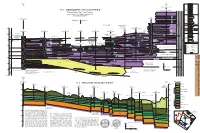

Plate Stratigraphic & Structure Cross Sections11 E

West East EXPLANATION M E E’ M Line intersection w/ B-B’ S M Upper Pan Glen Rose M 11-1 STRATIGRAPHIC CROSS SECTION E-E’ Geophysical Log & Samples (Kgru) S M Blanco River Dip Cross Section # # # Alex S. Broun, P.G., Douglas A. Wierman, P.G. # # and Wesley Schumacher M S F Wyn M Line intersection Geophysical Log Lower w/ C-C’ BLANCO CO. HAYS CO. Glen Rose M (Kgrl) S M M S G F Hensel (Khe) BLANCO RIVER Ap SB PR2 Upper Glen Rose: M Upper Trinity G G Upper Trinity Cow Creek ft LasM3 Upper Glen Rose (Kcc) 400 Limited Aquifer Geophysical Log & Samples Hammett Wall1 BLANCO (Kha) Ap SB PR1 Cie Sey Stl Nar Nel Arr Samples S G RIVER S M Geophysical Log Geophysical Log Geophysical Log Shell Core Geophysical Log Geophysical Log Sligo (Ksl) BLANCO RIVER 300 Lithology from Lederman Well S M Upper Aptian - Lower Albian Aptian - Lower Upper Stratotype Surface Sec. Offline one mile NW # Upper Glen Rose # Lower-Upper Sycamore/ “CA” Regional Marker Upper Glen Rose Glen Rose (1) Hosston Contact (Ksy/Kho) M 200 S F S KarstKarst Dinosaur tracks Little Blanco S F M measured section S F B. Hunt & S Lower Glen Rose BLANCO RIVER Burnet Ranch #1 S. Musick Shell core S Explanation M S Limestone (micr) Figure modified from Stricklin & S S F Lozo, 1971 and R.W. Scott, 2007 100 Limestone (skel) Lower Glen Rose Stratigraphic notes: Lower Glen Rose S Lower Glen Rose: Middle Trinity Aquifer LOWER CRETACEOUS Limestone (reef) 1- Edwards Group, Kainer Fm, as defined by Rose (1972). -

U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017

A Product of the Water Availability and Use Science Program Prepared in cooperation with the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Texas at San Antonio and hosted by the Student Geological Society and student chapters of the Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Association of Engineering Geologists U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017 Edited By Eve L. Kuniansky and Lawrence E. Spangler Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kuniansky, E.L., and Spangler, L.E., eds., 2017, U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023, 245 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175023. -

2005 Proceedings.Indd

Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science, Vol. 84 (2005) 215 UNDERDEVELOPED AND UNUSUAL XENACANTH SHARK TEETH FROM THE LOWER PERMIAN OF TEXAS Gary D. Johnson Department of Earth Sciences University of South Dakota Vermillion, SD 57069 ABSTRACT Xenacanth sharks from the Wichita and Clear Fork Groups in north-central Texas are represented by 51,400 isolated teeth, obtained by bulk-sampling sedi- ments at 65 localities, of Orthacanthus texensis (50% of total), O. platypternus (12%), Barbclabornia luedersensis (38%), and Xenacanthus slaughteri (0.01%) in Early Permian (late Sakmarian-Artinskian) strata spanning some 5 million years (285-280 Ma). Discounting deformed teeth (0.06%), which could usually be identified to species, there remain much more common underdeveloped teeth (1-2%?) and unusual teeth that are rare (<<0.1%). Teeth not fully developed, and presumably still within the dental groove when a shark died, lack the outer hypermineralized pallial dentine on the cusps, which display open pulp cavities; tooth bases possess a poorly developed apical button. Most could be assigned to the species of Orthacanthus, the remainder to B. luedersensis. Based on histologi- cal development in modern shark teeth, in which the base is last to develop, it would seem the reverse occurred in xenacanth teeth, but this conclusion is uncer- tain. Unusual teeth were most closely affiliated with Orthacanthus, but they pos- sess characters normally not associated with that genus, exceeding the presumed limits of variation that might be accepted for its heterodont dentition. Examples include teeth with cristated cusps, in which the distribution of cristae is highly asymmetrical; possession of a single cusp or of three equally developed principal cusps (two are normal in xenacanth teeth); and one tooth with a primary inter- mediate cusp that may have been larger than the principal cusps. -

North-Central Texas, USA: Implications for Western Equatorial Pangean Palaeoclimate During Icehouse–Greenhouse Transition

Sedimentology (2004) 51, 851–884 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2004.00655.x Morphology and distribution of fossil soils in the Permo-Pennsylvanian Wichita and Bowie Groups, north-central Texas, USA: implications for western equatorial Pangean palaeoclimate during icehouse–greenhouse transition NEIL JOHN TABOR* and ISABEL P. MONTAN˜ EZ *Department of Geological Sciences, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX 75275, USA (E-mail: [email protected]) Department of Geology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA ABSTRACT Analysis of stacked Permo-Pennsylvanian palaeosols from north-central Texas documents the influence of palaeolandscape position on pedogenesis in aggradational depositional settings. Palaeosols of the Eastern shelf of the Midland basin exhibit stratigraphic trends in the distribution of soil horizons, structure, rooting density, clay mineralogy and colour that record long-term changes in soil-forming conditions driven by both local processes and regional climate. Palaeosols similar to modern histosols, ultisols, vertisols, inceptisols and entisols, all bearing morphological, mineralogical and chemical characteristics consistent with a tropical, humid climate, represent the Late Pennsylvanian suite of palaeosol orders. Palaeosols similar to modern alfisols, vertisols, inceptisols, aridisols and entisols preserve characteristics indicative of a drier and seasonal tropical climate throughout the Lower Permian strata. The changes in palaeosol morphology are interpreted as being a result of an overall climatic trend from relatively humid and tropical, moist conditions characterized by high rainfall in the Late Pennsylvanian to progressively drier, semi-arid to arid tropical climate characterized by seasonal rainfall in Early Permian time. Based on known Late Palaeozoic palaeogeography and current hypotheses for atmospheric circulation over western equatorial Pangea, the Pennsylvanian palaeosols in this study may be recording a climate that is the result of an orographic control over regional- scale atmospheric circulation.