To View This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Cathedral Treasures: Celebrating Our Historic Collections' In

Day Conference 2017 19th June 2017, Canterbury Cathedral ‘Cathedral Treasures: celebrating our historic collections’ In the Cathedral Archives and Library reading room 10.15-11.00 Registration, coffee; welcome from Canon Christopher Irvine Overview of The Canterbury Journey project, by Mark Hosea, Project Director 11.00-11.45 The Very Rev Philip Hesketh, Rochester Cathedral: ‘Surviving an HLF project’ 11.45-12.45 Jon Alexander, ‘The New Citizenship Project’: ‘Working from mission to unlock the energy of your collection’; Rachael Bowers and Kirsty Mitchell, York Minster: ‘Cathedral Collections: unlocking spiritual capital’ 12.45-1.45 Lunch (in Cathedral Lodge) 1.45-2.30 AGM 2.30-3.00 Canon Christopher Irvine: ‘The place of the visual arts in cathedrals’ 3.00-3.30 Declan Kelly, Lambeth Palace: ‘Building a new home for Lambeth Palace Library’ 3.30-4.00 Conclusion, by the Very Rev Peter Atkinson, Dean of Worcester Cathedral, Chairman of the CLAA; tea 4.00-4.45 Tours: Cathedral Archives and Library, with Archives and Library staff Book and Paper Conservation, with Ariane Langreder, Head of Book and Paper Conservation Viewing of Nave conservation work from the safety deck, with Heather Newton, Head of Conservation (sensible footwear and head for heights required! Numbers limited.) ‘An artful wander’, with Canon Irvine (tour of artworks within the Cathedral) 5.30 Evensong Cost: £30 members; £40 non-members Canon Christopher Irvine is Canon Librarian and Director of Education at Canterbury Cathedral. He is a member of the Liturgical Commission of the Church of England and the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England, and is a trustee of Art and Christian Enquiry. -

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

Ludham Character Appraisal Adopted 7 December 2020

Ludham Conservation Area Apprasial August 2020 1 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Why have conservation areas? ............................................................................................. 3 Aims and Objectives .............................................................................................................. 5 What does designation mean for me? ................................................................................. 5 The Appraisal ............................................................................................................................. 7 Preamble ................................................................................................................................ 7 Summary of Special Interest ................................................................................................. 8 Location and Context ............................................................................................................ 9 General Character and Plan Form ........................................................................................ 9 Geological background ....................................................................................................... 10 Historic Development .............................................................................................................. 12 Archaeology and early development of the Parish .......................................................... -

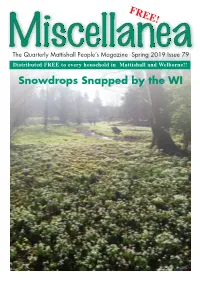

Snowdrops Snapped by the WI

The Quarterly Mattishall People’s Magazine Spring 2019 Issue 79 Snowdrops Snapped by the WI TUFTED INTERIORS 39 Norwich Street Dereham ĞĐŽŵĞĂ&ĂǁůƚLJdŽǁĞƌ&ŝdžĞƌ >ĞĂƌŶDŽƌĞĂďŽƵƚdƌĂĚŝƚŝŽŶĂůZĞƉĂŝƌdĞĐŚŶŝƋƵĞƐĨŽƌ,ŝƐƚŽƌŝĐƵŝůĚŝŶŐƐ Tel: 01362 695632 ĂƚƚŚĞ&t>dzdKtZ WE DON’T DABBLE ůů^ĂŝŶƚƐŚƵƌĐŚ͕tĞůďŽƌŶĞ͕EŽƌĨŽůŬ͕EZϮϬϯ>, ϲƚŚΘϳƚŚƉƌŝůϮϬϭϵ͕ϭϭ͘ϬϬĂŵͲϰ͘ϬϬƉŵ WE SPECIALISE IN FLOORING ϭϯƚŚΘϭϰƚŚƉƌŝůϮϬϭϵ͕ϭϭ͘ϬϬĂŵͲϰ͘ϬϬƉŵ With over 35 years experience in /ŶϮϬϭϴ͕ǁĞŚĞůĚĂƐĞƌŝĞƐŽĨĞdžƉĞƌƚůĞĚŚĂŶĚƐͲŽŶƐĞƐƐŝŽŶƐĨŽƌƉĞŽƉůĞƚŽůĞĂƌŶƚŽũŽLJƐŽĨƌĞƉĂŝƌŝŶŐŽůĚ ďƵŝůĚŝŶŐǁŝƚŚƚƌĂĚŝƚŝŽŶĂůƚĞĐŚŶŝƋƵĞƐ͘ the flooring trade selling, laying and dŚŝƐǁĂƐƐŽƐƵĐĐĞƐƐĨƵůĂŶĚĞŶũŽLJĂďůĞƚŚĂƚǁĞĂƌĞŐŽŝŶŐƚŽƌĞƉĞĂƚƚŚĞŽƉƉŽƌƚƵŶŝƚLJĨŽƌŶĞǁƉĞŽƉůĞƚŽ ďĞĐŽŵĞŝŶǀŽůǀĞĚ͕ĂŶĚĨŽƌŽƵƌ&ĂǁůƚLJdŽǁĞƌ&ŝdžĞƌƐƚŽůĞĂƌŶŵŽƌĞ͘ surveying, plus our vast selection dŚĞƌĞŝƐŶŽĐŚĂƌŐĞĨŽƌƚŚĞƐĞƉƌĂĐƚŝĐĂůƐĞƐƐŝŽŶƐĂŶĚŶŽƉƌŝŽƌŬŶŽǁůĞĚŐĞŽƌƐŬŝůůƐĂƌĞƌĞƋƵŝƌĞĚ͕ŽŶůLJĂŶ ŝŶƚĞƌĞƐƚŝŶůĞĂƌŶŝŶŐĂďŽƵƚƚƌĂĚŝƚŝŽŶĂůƌĞƉĂŝƌƚĞĐŚŶŝƋƵĞƐĨŽƌŚŝƐƚŽƌŝĐďƵŝůĚŝŶŐƐ͘ of patterns in every type of flooring, come to the specialists. So for all Your Carpet, Vinyls etc. Consult THE EXPERTS HOME VISITS ARRANGED DAY, EVENING OR WEEKEND TO SUIT CLOSED ALL DAY WEDNESDAY dŽĨŝŶĚŽƵƚŵŽƌĞĂŶĚƚŽƐŝŐŶƵƉĨŽƌƚŚĞƐĞƐƐŝŽŶƐ͘ WůĞĂƐĞĐŽŶƚĂĐƚZŝĐŚĂƌĚdŽŽŬ;ƌũƚϭϵϰϬΛŝĐůŽƵĚ͘ĐŽŵͿ͕ŽƌĞĂŶ^ƵůůLJ;Ě͘ƐƵůůLJΛƵĐů͘ĂĐ͘ƵŬͿ Open Tuesday — Saturday (closed sun/mon) by Kim ‘Spring into Roots’ Unisex Your local friendly Hair salon Up to date techniques and styling, offering high quality retail products at affordable prices. 5 Mill Street, Mattishall, Norfolk, NR20 3QG 2 Miscellanea Miscellanea From the Editor e won’t mention the ‘B’ word or make -

Church Bells

18 Church Bells. [Decem ber 7, 1894. the ancient dilapidated clook, which he described as ‘ an arrangement of BELLS AND BELL-RINGING. wheels and bars, black with tar, that looked very much like an _ agricultural implement, inclosed in a great summer-house of a case.’ This wonderful timepiece has been cleared away, and the size of the belfry thereby enlarged. The Towcester and District Association. New floors have been laid down, and a roof of improved design has been fixed b u s i n e s s in the belfry. In removing the old floor a quantity of ancient oaken beams A meeting was held at Towcester on the 17th ult., at Mr. R. T. and boards, in an excellent state of preservation, were found, and out of Gudgeon’s, the room being kindly lent by him. The Rev. R. A. Kennaway these an ecclesiastical chair has been constructed. The workmanship is presided. Ringers were present from Towcester, Easton Neston, Moreton, splendid, and the chair will be one of the ‘ sights ’ of the church. Pinkney, Green’s Norton, Blakesley, and Bradden. It was decided to hold The dedication service took place at 12.30 in the Norman Nave, and was the annual meeting at Towcester with Easton Neston, on May 16th, 189-5. well attended, a number of the neighbouring gentry and clergy being present. Honorary Members of Bell-ringing Societies. The officiating clergy were the Bishop of Shrewsbury, the Rev. A. G. S i e ,— I should be greatly obliged if any of your readers who are Secre Edouart, M.A. -

The 100 Medway Barge Match Frindsbury Cricketers

The 100th Medway Barge Match st On Saturday 31 May 2008, FOMA members boarded the Kingswear Castle for th the first trip of the summer to follow the 100 Medway Barge Match. Elaine Gardner, FOMA Committee Member, took some wonderful photographs of the race which features barges from Medway’s past: The Newsletter of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Edme, the eventual winner, at the start of the race Issue Number 11: August 2008 Cygnet, 1881, sails past 21st century shipping Frindsbury Cricketers This photograph from the collection of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre (FOMA) Chairman, Tessa Towner, will evoke memories of long hot (mythical) Kentish summers. Standing from left, John Walter (Tessa’s grandfather), 4th on left at back his brother Arthur (with peaked cap), known as Tom. Seated with cap, another brother, George Walter, landlord of the Royal Oak pub, Frindsbury. Also in the photo are probably several of the seven Skilton brothers, it was their father Joseph Skilton along with the Rev Jackson, vicar of Frindsbury, who started the Cricket Club in 1885. The date of the photograph has been narrowed down to about 1907 to 1909. Repertor, the first barge to reach the outer buoy Other possible names playing at this time were the Anderson brothers Colin and Donald (both killed in WWI), W.J.Coleman, A.Francis, H.Harpum, M.W.Lewry, A.Lines, A.E.Loach, N.McKechnie, D.Nye, and A.Ring. Inside this issue... We say goodbye to Stephen Dixon, Borough Archivist. After 18 years at the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre, Stephen left in June for a new post as Archive Service Manager at Essex Record Office, Chelmsford. -

The CWG Will Review Aspects of Cathedral Management And

The Archbishops of Canterbury and York have set up a Cathedrals Working Group, CWG, in response to a request made by the Bishop of Peterborough in his January 2017 Visitation Charge on Peterborough Cathedral for a revision to be carried out of the adequacy of the current Cathedrals Measure. The CWG will review aspects of cathedral management and governance and produce recommendations for the Archbishops on the implications of these responsibilities with regards to the current Cathedrals Measure. It will be chaired by the Bishop of Stepney, Adrian Newman, the former Dean of Rochester Cathedral, and the Dean of York, Vivienne Faull, will be the vice chair. The Working Group will look at a number of different areas of Cathedral governance, including training and development for cathedral deans and chapters, financial management issues, the procedure for Visitations, safeguarding matters, buildings and heritage and the role of Cathedrals in contributing to evangelism within their dioceses. The Bishop of Stepney and the Dean of York said: "Cathedrals contribute uniquely to the ecology of the Church of England, and we are a healthier, stronger church when they flourish. We are pleased to have this opportunity to review the structures that support their ministry, in order to enhance their role in church and society Cathedrals are one of the success stories of the Church of England, with rising numbers of worshippers. They are a vital part of our heritage and make an incalculable contribution to the life of the communities that they serve. This is an exciting opportunity for the Working Group to look at the different aspects of how Cathedrals work, and to ensure that the legislation and procedures they use are fit for purpose for their mission in the 21st century." The Group will report back initially to the Archbishops' Council, Church Commissioners and House of Bishops in December 2017. -

Kings Bromley Historians 2020

Kings Bromley Historians 2020 A Tribute to Dean Ernald Lane Ernald Lane was born in Kings Bromley on the third of March 1836. He was the fifth surviving child of John Newton Lane and his wife, Agnes (née Bagot) who had fourteen children of whom 8 survived to adulthood. John Newton Lane = Hon. Agnes Bagot (m 1828) ______________|_______________________ | | John Henry Bagot Lane = Susan Anne Vincent | 13 other children: [1829 –1886] (m 1864) [1832–1899] | 1. Albert William [1830-1831] | 2. Sidney Leveson [1831-1910] JP, Barrister | 3. William [1832- 1832] | 4. Cecil Newton [1833-1887] CMG | 5. Greville Charles [1834 –1878] Captain | 6. Ernald [1836 – 1913] Dean of Rochester | 7. Arthur Louis [1840–1846] | 8. Edward Alfred Reginald [1841–1854] RN | 9. Agnes Louisa [1842-1842] | 10. Alice Frances Jane [1844-1846] | 11. Edith Emmeline Mary [1846- 1929] | 12. Ronald Bertram [1847-1936] | 13. Isabel Emma Beatrice [1849-1876] Ernald was christened on 9th April 1836. His sponsors (a form of godparent) were: Hon. Rev. Daniel Finch, his great uncle Charles Earl Talbot The Viscountess Encombe (afterwards Countess of Eldon), his cousin Miss Humpage (His grandmother’s, blind Sarah Lane's, "Dame de Compagnie" or helper) The 1851 Census, which was taken on the 3rd March when Ernald was fifteen, shows a large family and establishment at Kings Bromley Hall: Status Age Occupation Where born Sarah Lane head 86 Esquire's Widow, Blind Shrewsbury John Newton Lane son 50 Magistrate & Deputy Lieutenant Aston, Warks Sidney Leveson Lane grandson 19 Undergraduate at Christ Chch. Coll. Blithfield Cecil Newton Lane grandson 17 Scholar at home Kings Bromley Greville Charles Lane grandson 16 Scholar at home Kings Bromley Ernald Lane grandson 15 Scholar at home Kings Bromley E. -

Glimpses of Medieval Norwich - Cathedral Precincts

Glimpses of Medieval Norwich - Cathedral Precincts This walk takes you through the historic Norwich Cathedral Close and along the river, which acted as part of Norwich’s defences. Walk: 1½ - 2 hours, some steps It is one of five trails to help you explore Norwich’s medieval walls, and discover other medieval treasures along the way. Work started on the walls in 1294 and they were completed in the mid-14th century. When completed they formed the longest circuit of urban defences in Britain, eclipsing even those of London. Today only fragments remain but, using these walking trails you will discover that much of Norwich’s medieval past. Route directions Notable features along the way Starting at the Forum, take the path to the left St Peter Mancroft was built in 1430 on the site of an earlier of St Peter Mancroft and walk through the church built by the Normans. It is one of the finest parish churchyard with Norwich Market on your left. churches in the country and well worth a visit. It was the first place in the world to have rung a true peel of bells on 2nd May 1715. 01 The Great Market was established between 1071 and 1075 02 following the Norman Conquest. Norwich’s market was originally in Tombland, which you will be visiting shortly. At the bottom of the slope turn left into Designed by notable local architect George Skipper the Royal Gentleman’s Walk. Arcade was built in 1899 on the coaching yard of the old Royal Hotel, retaining the old Royal's frontage. -

Archaeological Journal the Palace Or Manor-House of the Bishops of Rochester at Bromley, Kent, with Some Notes on Their Early Re

This article was downloaded by: [Northwestern University] On: 03 February 2015, At: 23:25 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Archaeological Journal Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 The Palace or Manor-House of the Bishops of Rochester at Bromley, Kent, with some Notes on their Early Residences Philip Norman LL.D., F.S.A. Published online: 17 Jul 2014. To cite this article: Philip Norman LL.D., F.S.A. (1920) The Palace or Manor- House of the Bishops of Rochester at Bromley, Kent, with some Notes on their Early Residences, Archaeological Journal, 77:1, 148-176, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1920.10853350 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1920.10853350 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Xk Roll the Sons and Daughters of the Anglican Church Clergy

kfi’ XK R O L L the son s an d d au g hters o f the A ng lican C hu rch C lerg y throu g hou t the w orld an d o f t h e Nav al an d M ilitary C h ap lains o f the sam e w h o g av e the ir liv es in the G re at War 1914- 1918 Q ua: reg io le rrw n os t ri n o n ple n a lo baris ' With th e mo m th se A n e l aces smile o g f , Wh i h I h ave lo v ed l s i ce and lost awh ile c ong n . , t r i r Requiem e e n am do na e is Dom n e e t lax pe pet ua luceat eis . PR INTED IN G REAT B RITA I N FOR TH E E NGLIS H CR A FTS ME L S OCIETY TD M O U TA L . N N , . 1 A KE S I GTO PLA CE W 8 , N N N , . PREFA C E k e R e b u t I have ta en extreme care to compil this oll as ac curately as possibl , it is al m ost t d m d ke d inevitable that here shoul be o issions an that mista s shoul have crept in . W d c d u e ith regar to the former , if su h shoul unfort nately prov to be the case after this k d can d d o d boo is publishe , all I o is t o issue a secon v lume or an appen ix to this ' d t h e d can d with regar to secon , all I o is to apologise , not for want of care , but for inac curate information . -

A History of the Hole Family in England and America

A History of the Hole Family in England and America BY CHARLES ELMER RICE, ALLIANCE, OHIO. ILLUSTRATED WITH 42 PORTRAITS AND ENGRAVINGS With Appendices on the Hanna, Grubb, DouglaS-Morton, Miller and Morris Families. Ti-IE R, Al, SCRANTON PUBLISHING CO., ALLIANCE, OHIO. ]~) \. '\_ ( I I l I~ j] 1 I j ) LIMITED EDITION, OF WHICH THIS IS NO.----- CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE. Norse aud Englisll origin of t:ie Hole Family.......... ............. 5 CHAPTER II. The Holes of Clannaborough.. ... ............... .. ... .. ....... .. ... ......... r r CHAPTER III. Genealogical Table from Egbert to Charles Hole..................... 16 CHAPTER IV. Tlle Holes of Devonsllire.... .... ......... ........ .... .......... ...... ........ 19 CHAPTER V. The Very Rev. Samuel Reynol·ls Hole, D~a.u of Rochester, and Samuel Hugh Francklin Hole. ... ......... ...... ......... ..... 22 CHAPTER VI. Generations from \Vi:liam the Conqueror to Jacob Hole........... 3l CHAPTER VII. The Fells of Swarthmoor Hall. ............. : .. 39 CHAPTER VIII. Tlle Descendant~ of Ti10mas and :\Iargaret Fell. ........ 50 CHAPTER IX. Descendants of the :\leads an<l Thomases ...... 53 CHAPTER X. Descendant,; of Jacob and Barbara Hole in the United States, excepting those of their son Charles Hole........... .............. 59 CHAPTER XI. Descendants of Charlf"s and M3ry Hole, excepting those of their oldest son, Jacob........................ ...... ....... ....................... 65 CHAPTER XII. Descendants of Jacob and l\Iary (Thomas) Hole, excepting those of their sons, Charles and John.......................................... 78 CHAPTER XIII. Descendants of Chas. Hole and Esther (Hanna) Hole. ..... 99 CHAPTER XI\'. Descendants of John Hole and Catharine (Hanna) Hole.. II 2 Memorial Pdge... ... ............ .. ...... ........ ........... ........ ............. .. 123 Appendix A. Notes on the Hanna Family............ .... ............ 124 Appendix B. Lineage of the Douglas Family (Earls of Morton) 127 Appendix C.