The Htstory and Sources of Conflict of Laws in Nigeria, with Comparisons to Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Law in the Nigerian Legal System Christian N

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 1997 International Law in the Nigerian Legal System Christian N. Okeke Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation 27 Cal. W. Int'l. L. J. 311 (1997) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE NIGERIAN LEGAL SYSTEM CHRISTIAN N. OKEKE· Table ofContents INTRODUCTION 312 ARGUMENT OF THE PAPER 312 DEFINITIONS 317 I. UNITED NATIONS DECADE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 321 II. HISTORICAL OUTLINE 323 A. Nigeria and Pre-Colonial International Law 323 B. Nigeria and "Colonial" International Law 326 C. The Place ofInternational Law in the Nigerian Constitutional Development 328 III. GENERAL DISPOSITION TOWARD INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE ESTABLISHED RULES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 330 IV. THE PLACE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW IN NIGERIAN MUNICIPAL LAW 335 V. NIGERIA'S TREATY-MAKING PRACTICE , 337 VI. ApPLICABLE LAW IN SELECTED QUESTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 339 A. International Human Rights and Nigerian Law 339 B. The Attitude ofthe Nigerian Courts to the Decrees and Edicts Derogating from Human Rights ............ 341 c. Implementation ofInternational Human Rights Treaties to Which Nigeria is a Party 342 D. Aliens Law .................................. 344 E. Extradition .................................. 348 F. Extradition and Human Rights 350 VII. -

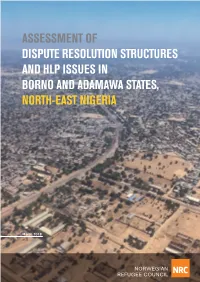

Assessment of Dispute Resolution Structures and Hlp Issues in Borno and Adamawa States, North-East Nigeria

ASSESSMENT OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION STRUCTURES AND HLP ISSUES IN BORNO AND ADAMAWA STATES, NORTH-EAST NIGERIA March 2018 1 The Norwegian Refugee Council is an independent humanitarian organisation helping people forced to flee. Prinsensgate 2, 0152 Oslo, Norway Authors Majida Rasul and Simon Robins for the Norwegian Refugee Council, September 2017 Graphic design Vidar Glette and Sara Sundin, Ramboll Cover photo Credit NRC. Aerial view of the city of Maiduguri. Published March 2018. Queries should be directed to [email protected] The production team expresses their gratitude to the NRC staff who contributed to this report. This project was funded with UK aid from the UK government. The contents of the document are the sole responsibility of the Norwegian Refugee Council and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or policies of the UK Government. AN ASSESSMENT OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION STRUCTURES AND HLP ISSUES IN BORNO AND ADAMAWA STATES 2 Contents Executive summary ..........................................................................................5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................................8 Recommendations ......................................................................................................................................................9 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................10 1.1 Purpose of -

The Universalism of the Magna Carta with Specific Reference to Freedom of Religion: Parallels in the Contemporary and Traditional Law of Nigeria

THE UNIVERSALISM OF THE MAGNA CARTA WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO FREEDOM OF RELIGION: PARALLELS IN THE CONTEMPORARY AND TRADITIONAL LAW OF NIGERIA. PRESENTED BY:- PROFESSOR AKIN IBIDAPO-OBE FACULTY OF LAW UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS AKOKA, LAGOS NIGERIA [email protected] [email protected] 234-8033943596 234-8188561624 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Magna Cartra is undoubtedly the most famous ‘human rights’ document in contemporary human history. Its popularity is attributable not only to its comparative antiquity, nor its source as emanating from one of the world’s “super powers” but to the universalism of its precepts. The many extrapolations and interpretations of its socially contextual provisions will be the focus of our discussion in segment one of this presentation, with particular reference to its religious antecedents. On the subject of religion,” an early clarification of our understanding of the concept might not be out of place as we will deal with other key concepts of the topic of discourse such as “the traditional or customary law of Nigeria” and the “contemporary law of Nigeria”. “Religion” Religion is a powerful media of the human essence, always present at every moment of our life, embedded in man’s innermost being and featuring in all the great and minor events of life – birth, education, adolescence, adulthood, work, leisure, marriage childbirth, well-being, sickness and, death. A. C. Bouquet tells us that “anyone, who is inside a worthy scheme of religion is well aware that to deprive him of that scheme is to a large extent, so to speak, to disembowel his life”. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page………………………………………………………………………………………….i Dedication..…………………………………………………………………...……….…….ii Certification…………………………………………………………………..………….… iii Acknowledgement……………………………………………….………….……………....iv Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………….……v Table of Legislation……………………………………………………………..………….vii Table of Cases………………………………………………………………….………….viii CHAPTER ONE 1.1 General Introduction 1 - 11 CHAPTER TWO 2.0 Overview of Widowhood Practice in Nigeria 12 - 13 2.1 South-South Nigeria – Edo/Rivers States 13 - 17 2.2 South-East Nigeria – Anambra/Imo States 17 - 19 2.3 South-West Nigeria – Ondo State 19 - 20 2.4 North-Central Nigeria – Benue 20 - 21 2.5 North-West Nigeria – Kano 21 - 22 2.6 North-East Nigeria - Bauchi 22 CHAPTER THREE 3.0 Health Implications of widowhood Practices 23 - 26 3.1 Economic effects of widowhood 26 - 27 CHAPTER FOUR Widows Rights and Inheritance 4.1 Customary Law 28 - 34 4.2 Common Law 35 - 48 4.3 Sharia Law 48 - 52 4.4 Widows’ Inheritance 52 - 54 4.5 Treatment of Widowers 55 - 59 4.6 Review of Legislative Interventions 59 - 80 CHAPTER FIVE 5.1 Recommendation (The Way Forward) 81 - 85 5.2 Conclusion 85 – 87 Schedule 88 - 89 TABLE OF LEGISLATION 1. Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution 2. Enugu State Laws on the Fundamental Rights of Widows and Widowers - 2001 3. African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights 4. Beijing Platform for Action 5. Convention of Political Rights of Women; 6. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); 7. International Bill of Rights: UDHR, ICCPR and ICESCR 8. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; 9. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); 10. -

Unitary Taxation of Multinational Enterprises for a Just Allocation of Income: Nigeria As a Case Study of Africa’S Largest Economies

Unitary Taxation of Multinational Enterprises for a Just Allocation of Income: Nigeria as a Case Study of Africa’s Largest Economies. By Alexander Ezenagu Faculty of Law McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2019 A Thesis submitted to McGill University In partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Civil Law © Alexander Ezenagu, 2019 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ACMT Alternative Corporate Minimum Tax AfCFTA African Continental Free Trade Agreement ALP Arm’s Length Principle APA Advance Pricing Agreement ATAF African Tax Administration Forum AU African Union BEPS Base Erosion and Profit Shifting BEPS Project BEPS Project of the OECD CAMA Companies and Allied Matters Act CbCR Country-by-Country Reports CCCTB Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base CFC Controlled Foreign Corporation CUP Comparable Uncontrolled Price ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States EOI Exchange of Information EU European Union FDI Foreign Direct Investment FIRS Federal Inland Revenue Service FPI Foreign Portfolio Investment GVCs Global Value Chains GPNs Global Production Networks GWCs Global Wealth Chains HLP High Level Panel IFF Illicit Financial Flow IMF International Monetary Fund MLI Multilateral Instrument MNE Multinational enterprise OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD MTC OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital 2 PCT Platform for Collaboration on Tax PE Permanent Establishment PSM Profit Split Method SDGs Sustainable Development Goals TIWB Tax Inspectors Without Borders TNMM Transactional -

The Constitution of the Federation of Nigeria (1960)

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERATION OF NIGERIA ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER I THE FEDERATION AND ITS TERRITORIES Section 1. Effect of this Constitution. 2. Establishment of the Federation. 3. Territories of the Federation. 4. Alteration of this Constitution. 5. Provisions relating to Regional constitutions. 6. Interpretation. CHAPTER II CITIZENSHIP 7. Persons who become citizens on 1st October 1960. 8. Persons entitled to be registered as citizens. 9. Persons naturalized or registered before 1st October, 1960. 10. Persons born in Nigeria after 30th September, 1960. 11. Persons born outside Nigeria after 30th September, 1960. 12. Dual citizenship. 13. Commonwealth citizens. 14. Criminal liability of Commonwealth citizens. 15. Powers of Parliament. 16. Interpretation. CHAPTER III FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS 17. Deprivation of life. 18. Inhuman treatment. 19. Slavery and forced labour. 20. Deprivation of personal liberty. 21. Determination of rights. 22. Private and family life. 23. Freedom of conscience. 24. Freedom of expression. 25. Peaceful assembly and association. 26. Freedom of movement 27. Freedom from discrimination. 28. Derogations from fundamental rights. 29. Reference to tribunal in certain cases. 30. Compulsory acquisition of property. 31. Special jurisdiction of High Courts in relation to this Chapter. 32. Interpretation CHAPTER IV THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL 33. Establishment of office of Governor-General. 34. Oaths to be taken by Governor-General. 35. Discharge of Governor-General's functions during vacancy, etc. CHAPTER V PARLIAMENT Part 1 Composition of Parliament 36. Establishment of Parliament. 37. Composition of Senate. 38. Composition of House of Representatives. 39. Qualifications for membership of Parliament. 40. Disqualifications for membership of Parliament, etc. 41. President of Senate. -

Measurement and Analysis of the Evolution of Institutions in Nigeria

Measurement and Analysis of the Evolution of Institutions in Nigeria David O. Fadiran, Mare Sarr, Johannes W. Fedderke ERSA working paper 665 February 2017 Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA) is a research programme funded by the National Treasury of South Africa. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the funder, ERSA or the author’s affiliated institution(s). ERSA shall not be liable to any person for inaccurate information or opinions contained herein. Measurement and Analysis of the Evolution of Institutions in Nigeria∗ David O. Fadiran† Mare Sarr‡ Johannes W. Fedderke§ 7th November 2016 Abstract “Institutions matter” has become a generally accepted premise in development economics. The growth and development problems in Nigeria are also common knowledge. To better understand these problems a proper characterization of institutions in Nigeria is essential. Conducting empirical test of the role of institutions in Nigeria’s growth and development can prove challenging due to lack of institu- tional data set that span over a long time. In the event that short span data set is available, Glaeser et al. (2004) highlight the many flaws implicit in such measures constructed by political scientists in literature. In this paper, we construct an index of institution quality for the period 1862 through to 2011 for Nigeria, in doing so, we adopt a new method of measuring institutions, which makes use of pre-existing (de jure) legislations, ordinances and constitutions in constructing three institutional indicators; civil and polit- ical liberties, freehold property rights, and non-freehold(customary) property rights. -

I the Social Stigmatisation of Involuntary Childless Women in Sub-Saharan Africa

The Social Stigmatisation of Involuntary Childless Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Gender Empowerment and Justice Case for Cheaper Access to Assisted Reproductive Technologies? This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hephzibah Egede Cardiff Law School September 2015 i DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii Summary This thesis considers the social stigmatisation of involuntary childlessness in Sub-Saharan Africa. It explores the socio-legal issues that arise when involuntary childlessness is given a gendered meaning and how this contributes to the social stigmatisation of involuntarily childless women in this developing region. -

The Legal Anatomy of Cultural Widowhood Practices in South Eastern Nigeria: the Need for a Panacea

Global Journal of Politics and Law Research Vol.3, No.1, pp.79-90, March 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) THE LEGAL ANATOMY OF CULTURAL WIDOWHOOD PRACTICES IN SOUTH EASTERN NIGERIA: THE NEED FOR A PANACEA. Mary Imelda Obianuju Nwogu (PhD Law) Lecturer, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, PMB 5025, Awka, Anambra State Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Nigeria is a patriarchal society, thus women are regarded as less human beings, especially among the Igbos of South Eastern Nigeria. Against this backdrop women are discriminated against, degraded and dehumanized despite the provisions of our local statutes such as the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended) and various other International Human Rights Instruments which Nigeria ratified. The widow is the fulcrum of this debased treatment. Widows are subjected to agonizing, painful and dehumanizing treatments during their mourning rites and thereafter. This impact negatively on their social, psychological and physical wellbeing. Surprisingly some of these obnoxious cultural practices are tacitly accepted and implemented by fellow women called the ‘Umuadas’. Hence, this paper examines the Igbo widowhood practices in South Eastern Nigeria and how the harmful widowhood rites can be eradicated. KEYWORDS: Culture, Widowhood Practices, South East, Nigeria, National Laws, Panacea. INTRODUCTION In Nigeria traditional practices have ensured that men retain material, social and moral dominance over women that they are simply unwilling to voluntarily relinquish. The woman is regarded as chattel (property) and this dominate its customary laws on marriage, inheritance, succession and property ownership. This consequently is manifested in the discriminatory and obnoxious traditional practices meted against widows in the South East of Nigeria, particularly the Igbos.The agony and sadness of a woman who lost her husband abound. -

Sharia Law in Nigeria: Can a Selective Imposition of Islamic Law Work in the Nation?

Journal of Islamic Studies and Culture December 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 66-81 ISSN: 2333-5904 (Print), 2333-5912 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jisc.v3n2a8 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/jisc.v3n2a8 Sharia Law In Nigeria: Can A Selective Imposition Of Islamic Law Work In The Nation? Gilbert Enyidah-Okey Ordu, Ph.D1 Abstract Originally, the radical Islamic movement in the Northern Nigeria was thought to be as a result of their poor socioeconomic infrastructures, poor governance, and the hatred for Nigeria’s interest in the Western lifestyles and education; their movement has interest in the Islamization of Nigeria as evidenced in the subtle and gradually submerged documents of the Islamic laws known as Sharia law in the 1999 Nigeria Constitution. This action is sensitively viewed as a‘hidden coup de-tat agenda’ in light of the rapid movement of the Sharia law in virtually all northern Muslim states in the nation. Why should the ideological Islamic legal principles of Sharia law (faith-based religion) occupy major sections of the Nigeria constitution? This is an indication of hidden agenda of the Muslim religion to turn the nation into an Islamic state.With great concern among Christians and the southern states, we surveyed259 Nigerians from various demographic backgrounds, to determine the degree of general perceptiveness of Islamization of Nigeria, the perceptiveness of Islamic legal ideological principle and its workability in Nigeria, the driving phenomena behind the imposition of Sharia law, the perceptiveness of Nigeria standing as one nation (in the midst of Islamic law), the perceptiveness of Nigeria as a nation at boiling-edge, political – economic instability as a result of Sharia law, and the perceptiveness of the Christian’s opposition of the imposition of Sharia law.The implications of the general legal operations of Sharia law were examined. -

Strengthening of Anti Corruption Commissions and Laws in Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt STRENGTHENING OF ANTI CORRUPTION COMMISSIONS AND LAWS IN NIGERIA by Fatima Waziri LL.B., Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, 2001 B.L., Nigeria Law School Lagos, 2002 LL.M., St Thomas University School of Law Miami, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Law School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF LAW This dissertation was presented by Fatima Waziri It was defended on November 21, 2011 and approved by Elena Baylis, Associate Professor, School of Law Roza Pati, Dr. iur, Associate Professor, School of Law Cecil Blake, Ph.D, Associate Professor, Africana Studies Dissertation Advisor: John Burkoff, Professor, School of Law ii Copyright © by Fatima Waziri 2011 iii STRENTHENING OF ANTI CORRUPTION COMMISSION AND LAWS IN NIGERIA Fatima Waziri, S.J.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This S.J.D. dissertation explores the role of law in challenging and curbing public corruption in Nigeria through the use of anti corruption agencies and laws. A comparative approach is used that draws upon development from other jurisdictions to illuminate issues in the Nigerian context. More broadly, this S.J.D. dissertation examined and analyzed the major anti corruption agencies and laws in Nigeria (Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission, Code of Conduct Bureau) and their approach towards corruption and democratic process. I also examined the role Freedom of Information Law plays in curbing corruption and promoting transparency, twelve years after the Freedom of Information Bill was first presented to the Nigerian National Assembly, it was finally passed into law May, 2011. -

Shari'ah Criminal Law in Northern Nigeria

SHARI’AH CRIMINAL LAW IN NORTHERN NIGERIA Implementation of Expanded Shari’ah Penal and Criminal Procedure Codes in Kano, Sokoto, and Zamfara States, 2017–2019 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM On the cover: A veiled Muslim woman sits before Islamic judge Nuhu Mohammed Dumi during a court trial over a matrimonial dispute at Unguwar Alkali Upper Sharia Court in Bauchi, Northern Nigeria, on January 27, 2014. AFP PHOTO / AMINU ABUBAKAR Photo: AMINU ABUBAKAR/AFP/Getty Images USCIRF | SHARI’AH CRIMINAL LAW IN NORTHERN NIGERIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SHARI’AH CRIMINAL LAW IN NORTHERN NIGERIA Implementation of Expanded Shari’ah Penal and Criminal Procedure Codes in Kano, Sokoto, and Zamfara States, 2017–2019 By Heather Bourbeau with Dr. Muhammad Sani Umar and Peter Bauman December 2019 www.uscirf.gov USCIRF | SHARI’AH CRIMINAL LAW IN NORTHERN NIGERIA Commissioners Tony Perkins Gary Bauer Chair Anurima Bhargava Gayle Manchin Tenzin Dorjee Vice Chair Andy Khawaja Nadine Maenza Vice Chair Johnnie Moore Executive Staff Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director Professional Staff Harrison Akins Patrick Greenwalt Dominic Nardi Policy Analyst Researcher Policy Analyst Ferdaouis Bagga Roy Haskins Jamie Staley Policy Analyst Director of Finance and Office Senior Congressional Relations Keely Bakken Management Specialist Policy Analyst Thomas Kraemer Zachary Udin Dwight Bashir Director of Operations and Project Specialist Director of Outreach and Policy Human Resources Scott Weiner Elizabeth K. Cassidy Kirsten Lavery Policy Analyst Director of Research and Policy International Legal Specialist Kurt Werthmuller Jason Morton Supervisory Policy Analyst Policy Analyst USCIRF | SHARI’AH CRIMINAL LAW IN NORTHERN NIGERIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by USCIRF ........................................................................................................................................