Annotated Bibliography Customary Marine Tenure In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framework for Prioritising Waterways for Management in Western Australia

Framework for prioritising waterways for management in Western Australia Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management University of Western Australia May 2011 Report no. CENRM120 Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management University of Western Australia Unit 1, Foreshore House, Proudlove Parade Albany Western Australia 6332 Telephone +61 8 9842 0837 Facsimile +61 8 9842 8499 www.cenrm.uwa.edu.au This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the University of Western Australia. Reference: Macgregor, C., Cook, B., Farrell, C. and Mazzella, L. 2011. Assessment framework for prioritising waterways for management in Western Australia, Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management, University of Western Australia, Albany. ISBN: 978-1-74052-236-6 Front cover credit: Bremer River, Eastern South Coast bioregion in May 2006, looking downstream by Geraldine Janicke. Disclaimer This document has been prepared by the Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management, University of Western Australia for the Department of Water, Western Australian. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith and on the basis that the Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management and its employees are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken, as the case may be in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. -

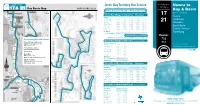

Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for Bus Nowra to Numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty

LOOK FOR BUS Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for bus Nowra to numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty. Ltd Transport initiative supplied by the Commonwealth of Australia and serviced by Nowra Coaches Bay & Basin Nowra Coaches Pty Ltd - Phone 4423 5244 Buses Servicing Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – (Weekdays) 17 Departs Nowra Wreck Bay Village 6.25am 9.10am 11.10am 12.45pm 2.17pm Huskisson Summercloud Bay 6.30am 9.15am 11.15am 12.48pm 2.22pm 21 Green Patch 6.40am 9.25am 11.25am 12.58pm 2.32pm Vincentia Jervis Bay Village 6.47am 9.32am 11.32am 1.05pm 2.39pm HMAS Creswell 6.50am 9.35am 11.35am 1.08pm 2.42pm Bay & Basin Visitors Centre 6.55am 9.42am 11.41am 1.13pm 2.48pm Vincentia 7.08am 9.53am 11.51am 1.23pm 2.58pm Central Avenue Bus Departs Tomerong To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 7.10am 9.55am – 1.25pm** 3.00pm **Services Sanctuary Point, St. Georges Basin & Basin View only. Routes (Via Bay & Basin) – – 11.53am – 3.30pm Connecting Bus Operators 732 Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – Saturday & Sunday Kennedy’s Bus and Coach Departs (Via Bay & Basin) 733 www.kennedystours.com.au See back cover for Tel: 1300 133 477 Wreck Bay Village 9.08am 1.20pm Summercloud Bay 9.13am 1.25pm detailed route descriptions Premier Motor Service Green Patch 9.23am 1.35pm www.premierms.com.au Jervis Bay Village 9.30am 1.42pm Price 50c Tel: 13 34 10 HMAS Creswell 9.33am 1.45pm Visitors Centre 9.38am 1.48pm Shoal Bus Tel: 02 4423 2122 Vincentia 9.48am 1.58pm Email: [email protected] Bus Departs To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 9.50am – Stuarts Coaches (Via -

Booderee National Park Management Plan 2015-2025

(THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK – INSIDE FRONT COVER) Booderee National Park MANAGEMENT PLAN 2015- 2025 Management Plan 2015-2025 3 © Director of National Parks 2015 ISBN: 978-0-9807460-8-2 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9807460-4-4 (Online) This plan is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Director of National Parks. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director of National Parks GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 This management plan sets out how it is proposed the park will be managed for the next ten years. A copy of this plan is available online at: environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/parks-australia/publications. Photography: June Andersen, Jon Harris, Michael Nelson Front cover: Ngudjung Mothers by Ms V. E. Brown SNR © Ngudjung is the story for my painting. “It's about Women's Lore; it's about the connection of all things. It's about the seven sister dreaming, that is a story that governs our land and our universal connection to the dreaming. It is also about the connection to the ocean where our dreaming stories that come from the ocean life that feeds us, teaches us about survival, amongst the sea life. It is stories of mammals, whales and dolphins that hold sacred language codes to the universe. It is about our existence from the first sunrise to present day. We are caretakers of our mother, the land. It is in balance with the universe to maintain peace and harmony. -

Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Bill 2015

Western Australia Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Bill 2015 Contents Preamble 2 1. Short title 3 2. Commencement 3 3. Noongar lands 3 4. Purpose 3 5. Recognition of the Noongar people 3 6. Effect of this Act 4 Schedule 1 — Noongar recognition statement Schedule 2 — Noongar lands: description Schedule 3 — Noongar lands: map 112—1 page i Western Australia LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Bill 2015 A Bill for An Act for the recognition of the Noongar people as the traditional owners of lands in the south-west of the State. page 1 Noongar (Koorah, Nitja, Boordahwan) (Past, Present, Future) Recognition Bill 2015 Preamble 1 Preamble 2 A. Since time immemorial, the Noongar people have 3 inhabited lands in the south-west of the State; these 4 lands the Noongar people call Noongar boodja (Noongar 5 earth). 6 B. Under Noongar law and custom, the Noongar people are 7 the traditional owners of, and have cultural 8 responsibilities and rights in relation to, Noongar 9 boodja. 10 C. The Noongar people continue to have a living cultural, 11 spiritual, familial and social relationship with Noongar 12 boodja. 13 D. The Noongar people have made, are making, and will 14 continue to make, a significant and unique contribution 15 to the heritage, cultural identity, community and 16 economy of the State. 17 E. The Noongar people describe in Schedule 1 their 18 relationship to Noongar boodja and the benefits that all 19 Western Australians derive from that relationship. 20 F. So it is appropriate, as part of a package of measures in 21 full and final settlement of all claims by the Noongar 22 people in pending and future applications under the 23 Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) for the 24 determination of native title and for compensation 25 payable for acts affecting that native title, to recognise 26 the Noongar people as the traditional owners of the 27 lands described in this Act. -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

43. Southwest Australian Shelf.Pdf

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs 839 XIX-64 Southwest Australian Shelf: LME #43 T. Irvine, J. Keesing, N. D’Adamo, M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams The Southwest Australian Shelf LME extends from the estuary of the Murray-Darling River to Cape Leeuwin on Western Australia’s coast (~32°S). It borders both the Indian and Southern Oceans and has a narrow continental shelf until it widens in the Great Australian Bight. The LME covers an area of about 1.05 million km2, of which 2.23% is protected, with 0.03% and 0.18% of the world’s coral reefs and sea mounts, respectively, as well as 10 major estuaries (Sea Around Us, 2007). This is an area of generally high energy coast exposed to heavy wave action driven by the West Wind Belt and heavy swell generated in the Southern Ocean. However, there are a few relatively well protected areas, such as around Albany, the Recherche Archipelago off Esperance, and the Cape Leeuwin / Cape Naturaliste region, with the physical protection facilitating relatively high marine biodiversity. Climatically, the LME is generally characterised by its temperate climate, with rainfall relatively high in the west and low in the east. However, rainfall is decreasing and Western Australia is getting warmer, with a 1°C rise in Australia predicted by 2030 (CSIRO, 2007) and an increase in the number of dry days also predicted. The overall environmental quality of the waters and sediments of the region is excellent (Environmental Protection Authority, 2007). The LME is generally low in nutrients, due to the seasonal winter pressure of the tail of the tropical Leeuwin Current and limited terrestrial runoff (Fletcher and Head, 2006). -

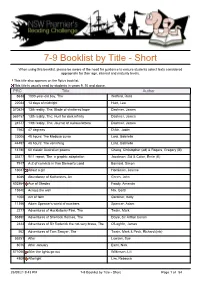

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title Author 5638 1000-year-old boy, The Welford, Ross 22034 13 days of midnight Hunt, Leo 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Dashner, James 569157 13th reality, The: Hunt for dark infinity Dashner, James 24577 13th reality, The: Journal of curious letters Dashner, James 7562 47 degrees D'Ath, Justin 23006 48 hours: The Medusa curse Lord, Gabrielle 44497 48 hours: The vanishing Lord, Gabrielle 14780 60 classic Australian poems Cheng, Christopher (ed) & Rogers, Gregory (ill) 33477 9/11 report, The: a graphic adaptation Jacobson, Sid & Colon, Ernie (ill) 7917 A-Z of convicts in Van Diemen's Land Barnard, Simon 16047 About a girl Horniman, Joanne 8086 Abundance of Katherines, An Green, John 602864 Ace of Shades Foody, Amanda 15540 Across the wall Nix, Garth 1058 Act of faith Gardiner, Kelly 11356 Adam Spencer's world of numbers Spencer, Adam 2277 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 55890 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan 2444 Adventures of Sir Roderick the not-very brave, The O'Loghlin, James 562 Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark & Peck, Richard (intr) 55251 After Lawson, Sue 8076 After January Earls, Nick 571050 After the lights go out Wilkinson, Lili 4809 Afterlight Lim, -

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. -

EARTH MOTHER CRYING: Encyclopedia of Prophecies of Peoples of The

EARTH MOTHER CRYING: Encyclopedia of Prophecies of Peoples of the Western Hemisphere, , , PART TWO of "The PROPHECYKEEPERS" TRILOGY , , Proceeds from this e-Book will eventually provide costly human translation of these prophecies into Asian Languages NORTH, , SOUTH , & CENTRAL , AMERICAN , INDIAN;, PACIFIC ISLANDER; , and AUSTRALIAN , ABORIGINAL , PROPHECIES, FROM "A" TO "Z" , Edited by Will Anderson, "BlueOtter" , , Compilation © 2001-4 , Will Anderson, Cabool, Missouri, USA , , Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson, "I am Mad Bear Anderson, and I 'walked west' in Founder of the American Indian Unity 1985. Doug Boyd wrote a book about me, Mad Bear : Movement , Spirit, Healing, and the Sacred in the Life of a Native American Medicine Man, that you might want to read. Anyhow, back in the 50s and 60s I traveled all over the Western hemisphere as a merchant seaman, and made contacts that eventually led to this current Indian Unity Movement. I always wanted to write a book like this, comparing prophecies from all over the world. The elders have always been so worried that the people of the world would wake up too late to be ready for the , events that will be happening in the last days, what the Thank You... , Hopi friends call "Purification Day." Thanks for financially supporting this lifesaving work by purchasing this e-Book." , , Our website is translated into many different languages by machine translation, which is only 55% accurate, and not reliable enough to transmit the actual meaning of these prophecies. So, please help fulfill the prophecy made by the Six Nations Iroquois Lord of the Confederacy or "Sachem" Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson -- Medicine Man to the Tuscaroras, and founder of the modern Indian Unity Movement -- by further supporting the actual human translation of these worldwide prophecy comparisons into all possible languages by making a donation, or by purchasing Book #1. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism.