The Making of a Radical Poetics: Modernist Forms in the Work of Bob Cobbing : Elements for an Exegesis of Cobbing’S Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'île De La Réunion Sous L'œil Du Cyclone Au Xxème Siècle. Histoire

L’île de La Réunion sous l’œil du cyclone au XXème siècle. Histoire, société et catastrophe naturelle Isabelle Mayer Jouanjean To cite this version: Isabelle Mayer Jouanjean. L’île de La Réunion sous l’œil du cyclone au XXème siècle. Histoire, société et catastrophe naturelle. Histoire. Université de la Réunion, 2011. Français. NNT : 2011LARE0030. tel-01187527v2 HAL Id: tel-01187527 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01187527v2 Submitted on 27 Aug 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE LA REUNION FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES L’île de La Réunion sous l’œil du cyclone au XXème siècle. Histoire, société et catastrophe naturelle. TOME I Thèse de doctorat en Histoire contemporaine présentée par Isabelle MAYER JOUANJEAN Sous la direction du Professeur Yvan COMBEAU Le jury : -Pascal Acot, C.R.H. C.N.R.S., H.D.R., Université de Paris I – Panthéon Sorbonne ; C.N.R.S. -Yvan Combeau, Professeur d’Histoire contemporaine, Université de La Réunion -René Favier, Professeur d’Histoire moderne, Université Pierre Mendès France – Grenoble II -Claude Prudhomme, Professeur d’Histoire contemporaine, Université Lumière - Lyon II -Claude Wanquet, Professeur d’Histoire moderne émérite, Université de La Réunion Soutenance - 23 novembre 2011 « Les effets destructeurs de ces perturbations de saison chaude, dont la fréquence maximale est constatée en février, sont bien connus, tant sur l’habitat que sur les équipements collectifs ou les cultures. -

Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry

Editorial How to Cite: Parmar, S. 2020. Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry. Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry, 12(1): 33, pp. 1–44. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/bip.3384 Published: 09 October 2020 Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro- duction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-profit publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Sandeep Parmar, ‘Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry.’ (2020) 12(1): 33 Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry. DOI: https://doi. org/10.16995/bip.3384 EDITORIAL Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry Sandeep Parmar University of Liverpool, UK [email protected] This article aims to create a set of critical and theoretical frameworks for reading race and contemporary UK poetry. By mapping histories of ‘innova- tive’ poetry from the twentieth century onwards against aesthetic and political questions of form, content and subjectivity, I argue that race and the racialised subject in poetry are informed by market forces as well as longstanding assumptions about authenticity and otherness. -

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits?

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits? Cornelia Gräbner erformance poetry in the Western world festival hall. A poem will be performed differently is a complex field—a diverse art form that if, for example, the poet knows the audience or has developed out of many different tradi- is familiar with their context. Finally, the use of Ptions. Even the term performance poetry can easily public spaces for the poetry performance makes a become misleading and, to some extent, creates strong case for poetry being a public affair. confusion. Anther term that is often applied to A third characteristic is the use of vernacu- such poetic practices is spoken-word poetry. At lars, dialects, and accents. Usually speech that is times, they are included in categories that have marked by any of the three situates the poet within a much wider scope: oral poetry, for example, or, a particular community. Oftentimes, these are in the Spanish-speaking world, polipoesía. In the marginalized communities. By using the accent in following pages, I shall stick with the term perfor- the performance, the poet reaffirms and encour- mance poetry and briefly outline some of its major ages the use of this accent and therefore, of the characteristics. group that uses it. One of the most obvious features of perfor- Finally, performance poems use elements that mance poetry is the poet’s presence on the site of appeal to the oral and the aural, and not exclu- the performance. It is controversial because the sively to the visual. This includes music, rhythm, poet, by enunciating his poem before the very recordings or imitations of nonverbal sounds, eyes of his audience, claims authorship and takes smells, and other perceptions of the senses, often- responsibility for it. -

Dick Higgins Papers, 1960-1994 (Bulk 1972-1993)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1d5n981n No online items Finding aid for the Dick Higgins papers, 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993) Finding aid prepared by Lynda Bunting. Finding aid for the Dick Higgins 870613 1 papers, 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993) ... Descriptive Summary Title: Dick Higgins papers Date (inclusive): 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993) Number: 870613 Creator/Collector: Higgins, Dick, 1938-1998 Physical Description: 108.0 linear feet(81 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: American artist, poet, writer, publisher, composer, and educator. The archive contains papers collected or generated by Higgins, documenting his involvement with Fluxus and happenings, pattern and concrete poetry, new music, and small press publishing from 1972 to 1994, with some letters dated as early as 1960. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Dick Higgins is known for his extensive literary, artistic and theoretical activities. Along with his writings in poetry, theory and scholarship, Higgins published the well-known Something Else Press and was a cooperative member of Unpublished/Printed Editions; co-founded Fluxus and Happenings; wrote performance and graphic notations for theatre, music, and non-plays; and produced and created paintings, sculpture, films and the large graphics series 7.7.73. Higgins received numerous grants and prizes in support of his many endeavors. Born Richard Carter Higgins in Cambridge, England, March 15, 1938, Higgins studied at Columbia University, New York (where he received a bachelors degree in English, 1960), the Manhattan School of Printing, New York, and the New School of Social Research, 1958-59, with John Cage and Henry Cowell. -

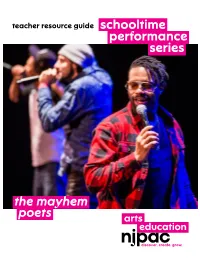

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

Word Is Seeking Poetry, Prose, Poetics, Criticism, Reviews, and Visuals for Upcoming Issues

Word For/ Word is seeking poetry, prose, poetics, criticism, reviews, and visuals for upcoming issues. We read submissions year-round. Issue #30 is scheduled for September 2017. Please direct queries and submissions to: Word For/ Word c/o Jonathan Minton 546 Center Avenue Weston, WV 26452 Submissions should be a reasonable length (i.e., 3 to 6 poems, or prose between 50 and 2000 words) and include a biographical note and publication history (or at least a friendly introduction), plus an SASE with appropriate postage for a reply. A brief statement regarding the process, praxis or parole of the submitted work is encouraged, but not required. Please allow one to three months for a response. We will consider simultaneous submissions, but please let us know if any portion of it is accepted elsewhere. We do not consider previously published work. Email queries and submissions may be sent to: [email protected]. Email submissions should be attached as a single .doc, .rtf, .pdf or .txt file. Visuals should be attached individually as .jpg, .png, .gif, or .bmp files. Please include the word "submission" in the subject line of your email. Word For/ Word acquires exclusive first-time printing rights (online or otherwise) for all published works, which are also archived online and may be featured in special print editions of Word For/Word. All rights revert to the authors after publication in Word For/ Word; however, we ask that we be acknowledged if the work is republished elsewhere. Word For/ Word is open to all types of poetry, prose and visual art, but prefers innovative and post-avant work with an astute awareness of the materials, rhythms, trajectories and emerging forms of the contemporary. -

All of a Sudden: the Role of Ἐξαίφνης in Plato's Dialogues

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 1-1-2014 All of a Sudden: The Role of Ἐξαιφ́ νης in Plato's Dialogues Joseph J. Cimakasky Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cimakasky, J. (2014). All of a Sudden: The Role of Ἐξαιφ́ νης in Plato's Dialogues (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/68 This Worldwide Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALL OF A SUDDEN: THE ROLE OF ἘΧΑΙΦΝΗΣ IN PLATO’S DIALOGUES A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Joseph Cimakasky May 2014 Copyright by Joseph Cimakasky 2014 ALL OF A SUDDEN: THE ROLE OF ἘΧΑΙΦΝΗΣ IN PLATO’S DIALOGUES By Joseph Cimakasky Approved April 9, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Ronald Polansky Patrick Lee Miller Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ John W. McGinley Professor of Philosophy (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Ronald Polansky Dean, McAnulty College Chair, Philosophy Department Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT ALL OF A SUDDEN: THE ROLE OF ἘΧΑΙΦΝΗΣ IN PLATO’S DIALOGUES By Joseph Cimakasky May 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Ronald Polansky There are thirty-six appearances of the Greek word ἐξαίφνης in Plato’s dialogues. -

Pure Psychic Chance Radio: 2016 Jim Leftwich

Pure Psychic Chance Radio: 2016 Jim Leftwich Table of Contents Pure Psychic Chance Radio: Essays 2016 1. Permission slips: Thinking and breathing among John Crouse's UNFORBIDDENS 2. ACTs (improvised moderate militiamen: "Makeshift merger provost!") 3. Applied Experimental Sdvigology / Theoretical and Historical Sdvigology 4. HOW DO YOU THINK IT FEELS: On The Memorial Edition of Frank O’Hara’s In Memory of My Feelings 5. mirror lungeyser: On Cy Twombly, Poems to the Sea XIX 6. My Own Crude Rituals 7. A Preliminary Historiography of an Imagined Ongoing: 1830, 1896, 1962, 2028... 8. In The Recombinative Syntax Zone. Two Bennett poems partially erased by Lucien Suel. In the Recombinative Grammar Zone. 9. Three In The Morning: Reading 2 Poems By Bay Kelley from LAFT 35 10. The Glue Is On The Sausage: Reading A Poem by Crag Hill in LAFT 32 11. My Wrong Notes: On Joe Maneri, Microtones, Asemic Writing, The Iskra, and The Unnecessary Neurosis of Influence 12. Noisic Elements: Micro-tours, The Stool Sample Ensemble, Speaking Zaum To Power 13. TOTAL ASSAULT ON THE CULTURE: The Fuck You APO-33, Fantasy Politics, Mis-hearing the MC5... 14. DIRTY VISPO: Da Vinci To Pollock To d.a.levy 15. WHERE DO THEY LEARN THIS STUFF? An email exchange with John Crouse 16. FURTHER SUBVERSION SEEMS IN ORDER: Reading Poems by Basinski, Ackerman and Surllama in LAFT 33 17. A Collage by Tom Cassidy, Sent With The MinneDaDa 1984 Mail Art Show Doc, Postmarked Minneapolis MN 07 Sep '16 18. DIRTY VISPO II (Henri Michaux, Christian Dotremont, derek beaulieu, Scott MacLeod, Joel Lipman on d.a.levy, Lori Emerson on the history of the term "dirty concrete poetry", Albert Ayler, Jungian mandalas) 19. -

Tomberg Rare Books Corrected Proof

catalog one tomberg rare books CATALOG ONE: Rare Books, Mimeograph Magazines, Art & Ephemera PLEASE DIRECT ORDERS TO: tomberg rare books 56 North Ridge Road Old Greenwich, CT 06870 (203) 223-5412 Email: [email protected] Website: www.tombergrarebooks.com TERMS: All items are offered subject to prior sale. Please email or call to reserve. Returns will be accepted for any reason with notification and within 14 days of receipt. Payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit cards or Paypal. Institutions may be billed according to their needs. Reciprocal courtesies to the trade. ALL BOOKS are first edition (meaning first printing) hardcovers in original dust jackets; exceptions noted. All items are guaranteed as described and in very good or better condition unless stated otherwise. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed and may be returned at any time if proven not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Medial mail can be requested and billed. INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING will vary depending upon destination and weight. Above: Item 4 Left: Item 19 Cover: Item 19, detail 1. [Artists’ Books]. RJS & KRYSS, T.L. DIALOGUE IN PALE BLUE Cleveland: Broken Press, 1969. First edition. One of 200 copies, each unique and assembled by hand. Consists entirely of pasted in, cut and folded blue paper constructions. Oblong, small quarto. Stiff wrappers with stamped labels. Light sunning to wrappers, one corner crease. Very good. rjs and tl kryss were planning on a mimeo collaboration but the mimeograph broke, leaving them with only paper. -

„To See Beneath the Surface of Lives“: Sherwood Andersons Winesburg

„T O SEE BENEATH THE SURFACE OF LIVES “: SHERWOOD ANDERSONS WINESBURG , OHIO , GERTRUDE STEIN UND DIE KUNST DER MODERNE Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philologie der Universität Hamburg Fakultät für Geistes- und Kulturwissenschaften, Institut Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Fachbereich Sprache, Literatur und Kultur Nordamerikas vorgelegt von Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach aus Hamburg Hamburg, 2007 Erstgutachter: Professor Dr. phil. Joseph C. Schöpp Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. phil. Bettina Friedl Tag des Vollzugs der Promotion 19. Juli 2006 1 Die Dinge sind alle nicht so fassbar und sagbar, als man uns meistens glauben machen möchte; die meisten Ereignisse sind unsagbar, vollziehen sich in einem Raume, den nie ein Wort betreten hat, und unsagbarer als alle sind die Kunstwerke, geheimnisvolle Existenzen, deren Leben neben dem unseren, das vergeht, dauert. (Rainer Maria Rilke) 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Modern Times ...............................................................................................................6 1.1 Die titelgebende Widmung ............................................................................................6 1.2 How to Read – und die Frage nach dem Schreiben.......................................................10 1.3.1 Gertrude Stein als „Mother of Modernism“?.............................................................14 1.3.2.1 Biographische Notiz ..............................................................................................15 1.3.2.2 Ansätze und Wege.................................................................................................17 -

Lee Harwood the INDEPENDENT, 5TH VERSION., Aug 14Odt

' Poet and climber, Lee Harwood is a pivotal figure in what’s still termed the British Poetry Revival. He published widely since 1963, gaining awards and readers here and in America. His name evokes pioneering publishers of the last half-century. His translations of poet Tristan Tzara were published in diverse editions. Harwood enjoyed a wide acquaintance among the poets of California, New York and England. His poetry was hailed by writers as diverse as Peter Ackroyd, Anne Stevenson, Edward Dorn and Paul Auster . Lee Harwood was born months before World War II in Leicester. An only child to parents Wilfred and Grace, he lived in Chertsey. He survived a German air raid, his bedroom window blown in across his bed one night as he slept. His grandmother Pansy helped raise him from the next street while his young maths teacher father served in the war and on to 1947 in Africa. She and Grace's father inspired in Lee a passion for stories. Delicate, gentle, candid and attentive - Lee called his poetry stories. Iain Sinclair described him as 'full-lipped, fine-featured : clear (blue) eyes set on a horizon we can't bring into focus. Harwood's work, from whatever era, is youthful and optimistic: open.' Lee met Jenny Goodgame, in the English class above him at Queen Mary College, London in 1958. They married in 1961. They published single issues of Night Scene, Night Train, Soho and Horde. Lee’s first home was Brick Lane in Aldgate East, then Stepney where their son Blake was born. He wrote 'Cable Street', a prose collage of location and anti fascist testimonial. -

Atsignofreinep00fran.Pdf

Design by Aubrey Beardsley OAK ST. Rn<5F Return this book on or before the Latest Date stamped below. University of Illinois Library DEC 1 3 195 -UIBR.AR.Y OF THE. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT THE SIGN OF THE REINE PEDAUQUE I Return this book on or betore the Latest Date stamped below. A rue T>EFiNiTive AT THE SIGN of the REINE PEDAUQUE DODD-MEAD & COMPANY Published in U. S. A.. 192?, by DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, INC, PRINTED IN u. s. A, PAGB vii PREFACE i CHAPTER I 4 II 15 " III 21 iv 26 "V 44 VI 53 VII 60 " VIII 66 IX 7i X 79 XI 87 XII 92 " XIII 106 XIV no XV 127 " XVI 134 " XVII 165 " XVIII 188 XIX 247 XX 255 XXI 259 " XXII 263 " XXIII 266 " XXIV 272 I 1 67239 INTRODUCTION HE novel of which the following pages are a translation was pub- lished in 1893, the author's forty- ninth year, and comes more or less midway in the chronological list of his works. It thus marks the flood tide of his genius, when his imagina- tive power at its brightest came into conjunction with the full ripeness of his scholarship. It is, per- haps, the most characteristic example of that elu- sive point of view which makes for the magic of Anatole France. No writer is more personal. No writer views human affairs from a more imper- sonal standpoint. He hovers over the world like a disembodied spirit, wise with the learning of all times and with the knowledge of all hearts that have beaten, yet not so serene and unfleshly as not to have preserved a certain tricksiness, a capacity for puckish laughter which echoes through his pages and haunts the ear when the covers of the book are closed.