Park-Above-Parking Downtown: a Spatial-Based Impact Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm to Launch "Chris Carter's British Invasion" on Little Steven Van Zandt's Underground Garage Channel

SiriusXM to Launch "Chris Carter's British Invasion" on Little Steven Van Zandt's Underground Garage Channel New weekly show featuring music from the British Invasion to be hosted by renowned British music expert and Underground Garage host, Chris Carter NEW YORK, April 3, 2013 /PRNewswire/ -- Sirius XM Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) today announced that it will premiere Chris Carter's British Invasion, a new weekly three-hour show dedicated to the artists and music of the British Invasion, on Sunday, April 7, at 9:00 am ET. (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20101014/NY82093LOGO) Chris Carter's British Invasion will cover all aspects of the British Invasion and feature artist interviews as well as hits, album tracks, B-sides, and live recordings from iconic artists including The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Mott The Hoople, The Move, The Creation, Oasis, and many more. "Chris Carter's British Invasion will be an exciting addition to our weekend lineup of music programming for the generation that lived it and for those who missed it," said Scott Greenstein, President and Chief Content Officer, SiriusXM. "There is no one better than Chris Carter to guide SiriusXM listeners nationwide through the hits and album tracks from one of the most vibrant, groundbreaking, and fun musical periods in rock." "As listeners already know, the British Invasion of 1964 to 1968 is the heart of the Underground Garage format here on SXM 21, but this will be our first show dedicated to the music and era that defines our identity," said Steven Van Zandt, creator and producer of SiriusXM's Little Steven's Underground Garage channel and E Street band member. -

State of the River 2006-07

State of the River 2006–07 iver Renaissance is the City of Portland’s initiative to reclaim the Willamette River as a community centerpiece, and sustain our connection with the Columbia River. The Willamette is the heart of Portland’s landscape, history, and culture. The Columbia is our economic and ecologic lifeline to the Pacific. River Renaissance Rpromotes and celebrates these waters as living emblems of Portland’s identity. Portland lives its river values every day in ways big and small. Together these actions are reconnecting citizens and businesses with a healthier river. The State of the River Report profiles yearly accomplishments and identifi es future actions needed to assure a clean and healthy river, a prosperous harbor, and vibrant riverfronts. Just a few of the actions detailed in this report are illustrated on this page to give some idea of how deeply Portland believes in caring for—and being cared for by—our rivers. 2006–07 State of the River Report Contents River Renaissance is a Leadership . 2 community-wide initiative to Message from the River Renaissance Directors . 3 reclaim the Willamette River Introduction . 4 as Portland’s centerpiece, and sustain our connection with the How the City that Works Works on the River . 5 Columbia River. The initiative Accomplishments and Key Actions . 7 promotes and celebrates Portland’s Progress Measures . 23 waters as our chief environmental, 2007–2008 Action Agenda . 35 economic and urban asset. Up and Down the Willamette . 55 Partners . 61 Recommended Readings . 63 The 2006–07 State of the River Report summarizes the achievements made by the City of Portland and a network of community partners to revitalize our rivers and identifies next steps needed to continue progress. -

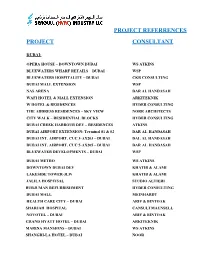

Please See a List of Our Project References

PROJECT REFERRENCES PROJECT CONSULTANT DUBAI: OPERA HOUSE – DOWNTOWN DUBAI WS ATKINS BLUEWATERS WHARF RETAILS – DUBAI WSP BLUEWATERS HOSPITALITY – DUBAI CKR CONSULTING DUBAI MALL EXTENSION WSP NAS ARENA DAR AL HANDASAH WAFI HOTEL & MALL EXTENSION ARKITEKNIK W HOTEL & RESIDENCES HYDER CONSULTING THE ADDRESS RESIDENCES – SKY VIEW NORR ARCHITECTS CITY WALK – RESIDENTIAL BLOCKS HYDER CONSULTING DUBAI CREEK HARBOUR DEV – RESIDENCES ATKINS DUBAI AIRPORT EXTENSION- Terminal 01 & 02 DAR AL HANDASAH DUBAI INT. AIRPORT, CUC 3-AX203 – DUBAI DAL AL HANDASAH DUBAI INT. AIRPORT, CUC 5-AX205 – DUBAI DAR AL HANDASAH BLUEWATER DEVELOPMENTS – DUBAI WSP DUBAI METRO WS ATKINS DOWNTOWN DUBAI DEV KHATIB & ALAMI LAKESIDE TOWER-JLW KHATIB & ALAMI JALILA HOSPITSAL STUDIO ALTIERI BURJUMAN REFURBISHMENT HYDER CONSULTING DUBAI MALL MEINHARDT HEALTH CARE CITY – DUBAI ARIF & BINTOAK SHARJAH HOSPITAL CANSULTMAUNSELL NOVOTEL – DUBAI ARIF & BINTOAK GRAND HYATT HOTEL – DUBAI ARKITEKNIK MARINA MANSIONS – DUBAI WS ATKINS SHANGRI-LA HOTEL – DUBAI NOOR PROJECT REFERRENCES PROJECT CONSULTANT AL BASSAM TOWER – DUBAI WS ATKINS REEF MALL - DUBAI RMJM BRIGHT START TOWER – DUBAI WS ATKINS DUBAI INT. FINANCIAL CENTRE – DUBAI RMJM AL SALAM TOWER – DUBAI WS ATKINS AL MANKHOOL TOWER – DUBAI WS ATKINS JUMEIRA BEACH RESIDENCE - 01 – DUBAI HYDER CONSULTING JUMEIRA BEACH RESIDENCE – 03 – DUBAI ARENCO JUMEIRA BEACH RESIDENCE – 04 – DUBAI ARIF & BINTOAK DUBAI FESTIVAL CITY – DUBAI HYDER CONSULTING BUR JUMAN EXPANSION PROJECT – DUBAI DAR AL HANDASAH DWTC HALL 8 – DUBAI RMJM DWTC HALLS 1 & 2 – DUBAI RMJM POLICE NEW HEADQUARTERS - DUBAI ARENCO ZABEEL PARK – DUBAI WS ATKINS D.I.A – FUEL STAGING AREA-AX253 DAR AL HANDASAH FLOWER CENTRE D.I.A – DUBAI WS ATKINS ATLANTIS PROJECT - DUBAI NORR GROUP IBIS HOTEL – DUBAI ARIF & BINTOAK DUBAI MARINA – SOUTH MARINA MOTT MacDONALD CINE STAR CINEMA – DUBAI RMJM KNOWLEDGE VILLAGE – DUBAI IAN BANHAM EMIRATES INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL – DUBAI CONSULTAIR H.H. -

Major Events in Portland Planning History: Pioneer Courthouse Square

Portland State University PDXScholar Ernie Bonner Collection Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 4-11-2004 Major Events in Portland Planning History: Pioneer Courthouse Square Ernest Bonner Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_bonner Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bonner, Ernest, "Major Events in Portland Planning History: Pioneer Courthouse Square" (2004). Ernie Bonner Collection. 302. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_bonner/302 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ernie Bonner Collection by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Major Events in Portland Planning History: Pioneer Courthouse Square personal files] 1980-08-22 PDC Organizational Meeting. Items discussed include: - It will take $100-200,000 for fund raising and events; - Architect will do sketch on painting the square; - Architect to provide outline of items to be donated. PDC has budgeted $50,000 for interim use related items, i.e., painting the square; - Mike Cook wants proposal from Architect on fee and product on the various phases of work, street right of way not in main contract. Will Martin notes to file [in Mark Bevins personal files] 1980-08-25 Meeting with Bob Packard (Zimmer Gunsul Frasca) on Light Rail Transit station planning. First fee breakdown by M. Bevins and J. Matteson. 1980-08-27 Meeting on street improvements. Architect asked to break down improvements into phasing for grant proposal, also must determine street profile at interface with Square. -

Siriusxm.Com/Business © 2018 Sirius XM Radio Inc

SATELLITE CHANNEL GUIDE COMMERCIAL-FREE MUSIC • ENDLESS VARIETY • EXCLUSIVE CHANNELS • ORIGINAL & RARE FORMATS • LIVE PERFORMANCES POP CHRISTIAN 02 SiriusXM Hits 1 Today’s Pop Hits 34 Lithium ’90s Alternative/Grunge 63 The Message Christian Pop & Rock 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 35 SiriusXMU New Indie Rock 64 Kirk Franklin’s Praise Kirk Franklin’s Gospel Channel 04 SiriusXM Spotlight Discover Amazing Channels 36 Alt Nation New Alternative Rock 65 enLighten Southern Gospel 05 ’50s on 5 ’50s Pop Hits 37 Octane New Hard Rock JAZZ/STANDARDS 06 ’60s on 6 Pop Hits with Cousin Brucie 38 Ozzy’s Boneyard Ozzy’s Classic Hard Rock 66 Watercolors Smooth/Contemporary Jazz 07 ’70s on 7 Pop Hits with American Top 40 39 Hair Nation ’80s Hair Bands 67 Real Jazz Classic Jazz 08 ’80s on 8 Pop Hits with Original MTV VJs 41 SiriusXM Turbo ’90s/2000s Hard Rock XL 68 Spa New Age ’90s Pop Hits 69 Escape Easy Listening 09 Pop Hits with Downtown Julie Brown HIP-HOP 10 Pop2K 2000s Pop Hits 70 SiriusXM Love Love Songs 43 Rock the Bells Radio “Classic” Hip-Hop with LL Cool J XL Siriusly Sinatra 13 Pitbull’s Globalization 71 Standards by Sinatra & More Worldwide Rhythmic Hits 44 Hip-Hop Nation Today’s Hip-Hop Hits XL The Coffee House 72 On Broadway Show Tunes 14 Acoustic/Singer-Songwriters R&B 73 ’40s Junction ’40s Pop Hits/Big Band 15 The Pulse Adult Pop Hits 42 The Joint Reggae 74 B.B. King’s Bluesville 16 The Blend Bright Pop Hits B.B. -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music -

1048 S Los Angeles Street Is Located Less Than Three Miles from the Ferrante, a Massive 1,500-Unit Construction Project, Scheduled for Completion in 2021

OFFERING MEMORANDUM A Signalized Corner Mixed-Use Retail and Office Property Ideally located in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in the Iconic Fashion District brandonmichaelsgroup.com INVESTMENT ADVISORS Brandon Michaels Senior Managing Director of Investments Senior Director, National Retail Group Tel: 818.212-2794 [email protected] CA License: 01434685 Matthew Luchs First Vice President Investments COO of The Brandon Michaels Group Tel: 818.212.2727 [email protected] CA License: 01948233 Ben Brownstein Senior Investment Associate National Retail Group National Industrial Properties Group Tel: 818.212.2812 [email protected] CA License: 02012808 Contents 04 Executive Summary 10 Property Overview 16 Area Overview 28 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS Executive Summary 4 1048 S. Los Angeles St The Offering A Signalized Corner Mixed-Use Retail and Office Property Ideally located in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in the Iconic Fashion District The Brandon Michaels Group of Marcus & Millichap has been selected to exclusively represent for sale 1048 South Los Angeles Street, a two-story multi-tenant mixed-use retail and office property ideally located on the Northeast signalized corner of Los Angeles Street and East 11th Street. The property is comprised of 15 rental units, with eight retail units on the ground floor, and seven office units on the second story. 1048 South Los Angeles Street is to undergo a $170 million renovation. currently 86% occupied. Three units are The property is located in the heart of vacant, one of which is on the ground the iconic fashion district of Downtown floor, and two of which are on the Los Angeles, which is home to over second story. -

Iii. Environmental Setting

III. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING This Section provides a brief overview of the Project Site’s regional and local setting. Additional descriptions of the environmental setting as it relates to each of the environmental issues analyzed in this EIR are included in the environmental setting discussions contained within Sections IV.A through IV.N of this EIR. A list of related projects, which is used as the basis for the discussion of cumulative impacts in each section is also provided. 1. OVERVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING a. Regional Setting b. Local Setting and Land Uses c. Surrounding Land Uses 2. RELATED PROJECTS Wilshire Grand Redevelopment Project III. Environmental Setting Draft Environmental Impact Report Page III-1 City of Los Angeles July 2010 1. OVERVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING a. Regional Setting The Project Site is located in Los Angeles County, in the Central City (downtown) area of the City of Los Angeles (the “City”) (see Section II [Project Description], Figure II-1 [Regional and Project Vicinity Map]). The Project Site is also located in the Financial Core district of downtown Los Angeles, which is bordered by South Park to the south and southwest, the Historic Core to the east and southeast, Bunker Hill to the north and northeast, and City West to the west and northwest across the US/Interstate 110 (the “Harbor Freeway”) (see Figure II-3 [Downtown Context Map] in Section II [Project Description]). Regional access to the Project Site is provided via the Harbor Freeway approximately 0.04 mile west of the Project Site. Wilshire Boulevard, Figueroa Street, and Olympic Boulevard serve as the primary arterial roadways providing access to the area surrounding the Project Site. -

Dubai Assured Approved Establishments

Dubai Assured approved establishments 19/07/2020 Hotels 2 2 اﻟﻔﻨﺎدق Attractions 27 27 ﻣﻨﺎﻃﻖ اﻟﺠﺬب اﻟﺴﯿﺎح Public parks 28 28 اﻟﺤﺪاﺋﻖ اﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ Shopping centres 29 29 ﻣﺮاﻛﺰ اﻟﺘﺴﻮق Cinemas 31 31 دور اﻟﺴﯿﻨﻤﺎ Commercial establishments 32 32 اﻟﻤﻨﺸﺂت اﻟﺘﺠﺎرﯾﺔ Souqs 34 34 اﻷﺳﻮاق Public beaches 35 35 اﻟﺸﻮاﻃﺊ اﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ Heritage sites 36 36 اﻟﻤﻮاﻗﻊ اﻟﺘﺮاﺛﯿﺔ 1 اﻟﻔﻨﺎدق Hotels ﻓﻨﺪق 24 ﺟﻮﻟﺪ ش.ذ.م.م GOLD HOTEL L.L.C 24 ﻓﻨﺪق اﯾﻪ اس ﻓﻲ ش.ذ.م.م A S V HOTEL L.L.C أﺑﯿﺪوس ﻟﻠﺸﻘﻖ اﻟﻔﻨﺪﻗﯿﻪ اﻟﺒﺮﺷﺎء ش.ذ.م.م ABIDOS HOTEL APARTMENT ALBARSHA L.L.C أﺑﯿﺪوس ﻟﻠﺸﻘﻖ اﻟﻔﻨﺪﻗﯿﻪ ش.ذ.م.م ABIDOS HOTEL APARTMENT L.L.C ﻓﻨﺪق أﺑﺠﺪ ﺟﺮاﻧﺪ ش.ذ.م.م ABJAD GRAND HOTEL L.L.C اداﺟﯿﻮ ﺑﺮﯾﻤﯿﻢ ﻟﻠﺸﻘﻖ اﻟﻔﻨﺪﻗﯿﺔ اﻟﺒﺮﺷﺎء ADAGIO PREMIUM HOTEL APARTMENT ALBARSHA اﻟﻌﻨﻮان ﺑﻮﻟﯿﻔﺎرد ش.ذ.م.م ADDRESS BOULEVARD L.L.C اﻟﻌﻨﻮان ﻓﺎوﻧﺘﻦ ﻓﯿﻮز ش.ذ.م.م ADDRESS FOUNTAIN VIEWS L.L.C اﻟﻌﻨﻮان ﺳﻜﺎي ﻓﯿﻮ ذ.م.م ADDRESS SKY VIEW L.L.C (ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﻮﺣﺪة (ذ.م.م (AL - WEHDA HOTEL (L.L.C ﻓﻨﺪق اﻻﺣﺮار AL AHRAR HOTEL ﻓﻨﺪق اﻻﻣﺎﻧﺔ AL AMANA HOTEL ﻓﻨﺪق اﻻﻧﺪﻟﺲ ش.ذ.م.م AL ANDALUS HOTEL L.L.C ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﺒﺎﺣﺔ AL BAHA HOTEL اﻟﺒﺮﺷﺎء ﻟﻠﺸﻘﻖ اﻟﻔﻨﺪﻗﯿﺔ ش.ذ.م.م AL BARSHA HOTEL APARTMENTS L.L.C - اﻟﺒﺴﺘﺎن رزﯾﺪﻧﺲ (ﻓﺮع) ﺷﺮﻛﺔ ﻣﺮﻛﺰ اﻟﺒﺴﺘﺎن - ذ. م. م (.AL BUSTAN RESUDENCE (L.L.C ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﺪار AL DAR HOTEL اﻟﻀﯿﺎﻓﺔ ﻟﻠﺸﻘﻖ اﻟﻔﻨﺪﻗﯿﺔ AL DEYAFA HOTEL APARTMENTS 3 3 ﻣﻨﺘﺠﻊ اﻟﺤﺒﺘﻮر ﻟﻠﺒﻮﻟﻮ ذ.م.م AL HABTOOR POLO RESORT L.L.C ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﻬﺎﺷﻤﻲ AL HASHEMI HOTEL 2 ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﺠﻮﻫﺮة ﺟﺎردﻧﺰ AL JAWHARA GARDENS HOTEL اﻟﺠﻮﻫﺮة ﻟﻠﺸﻘﻖ اﻟﻔﻨﺪﻗﯿﺔ AL JAWHARA HOTEL APARTMENT ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﺠﻮﻫﺮة ﻣﺘﺮو AL JAWHARA METRO HOTEL ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﺠﺰﯾﺮة AL JAZEERA HOTEL ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﻜﺮاون AL KARAWAN HOTEL ﻓﻨﺪق اﻟﻜﺮﻧﻚ ش.ذ.م.م AL KARNAK HOTEL -

District Energy Space 2019

■ North America District Energy Space 2019 Spotlighting Industry Growth 2019: More than 180 million square feet reported Over 2.5 billion square feet reported since 1990 District■ North America Energy Space 2019 Industry Growth Around the World Dedicated to the growth and utilization of district energy as a means to enhance energy efficiency, provide more sustainable, reliable and resilient energy infrastructure, and contribute to improving the global environment. The publication of District Energy Space has become an annual tradition for the International District Energy Association (IDEA) since 1990. Compilations beyond North America were initiated in 2004. This issue features a compilation of data provided by our members including the number of buildings and their area in square feet that have been committed or recommitted to district energy service in North America during calendar year 2019, or previously unreported for recent years. Each year, IDEA asks its member systems to provide information on buildings that committed or recommitted to district energy service during the previous calendar year. To qualify for consideration in District Energy Space, a renewal must be a contracted building or space that had been scheduled to expire during the calendar year and was renewed under a contract with a duration of 10 years or more. Year-to-year rollover--simple continuation of service to existing buildings is not considered renewal. Established in 1909, the International District Energy Association serves as a vital communications and information hub for the district energy industry, connecting industry professionals and advancing the technology around the world. With headquarters just outside of Boston, Mass., IDEA comprises over 2,400 district heating and cooling system executives, managers, engineers, consultants and equipment suppliers from 25 countries. -

Internet Channel Guide

STREAMING Channel Guide DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 63 Contemporary Christian Christian Pop & Rock 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 28 Adult Alternative New/Classic Alt Rock 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative 90s Alternative/Grunge 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock New Alt Rock 68 New Age New Age 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Singer-Songwriters Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 15 Pop Mix Modern Adult Pop Hits 49 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Blend of Bright Pop Hits 51 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 17 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 24 Radio Margaritaville Escape to Margaritaville 56 New Country Today’s New Country 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Radio B.B. King’s Bluesville B.B. King’s Blues Channel POP 310 Rock Hall Inducted Artists 74 04 SoulCycle Radio Music to Energize Your Soul 311 Yacht Rock Radio ’70s/’80s Smooth-Sailing Soft Rock -

Pioneer Courthouse Square Market Research Results

Portland State University PDXScholar Portland City Archives Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 1-1-1984 Pioneer Courthouse Square Market Research Results Keith L. Crawford Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityarchives Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Crawford, Keith L., "Pioneer Courthouse Square Market Research Results" (1984). Portland City Archives. 97. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityarchives/97 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Portland City Archives by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. PIONEER COURTHOUSE SQUARE MARKET RESEARCH SURVEY RESULTS Conducted in cooperation with Portland State University Under the auspices of Pioneer Courthouse Square of Portland, Inc By Keith L. Crawford Copyright 1984, all rights reserved. PIONEER COURTHOUSE SQUARE MARKET RESEARCH SURVEY TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Acknowledgements i Introduction ii The reason and the method • iii SURVEY RESULTS: All about the Brickowners Where they live 1 Their relatives before 1900 2 Their ancestors who attended Central School 3 The Portland Hotel Their stories about the Portland Hotel 4 The Meier & Frank parking lot - 5 When they visit downtown When they got involved with the Square How they heard about the fundraising 6 Most effective