3.1 Measuring Tobacco Use Behaviours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price Name Price Name €13.20 €13.20 €13.20 €13.20 €13.20

Cigarette Price List Effective 09th October 2019 Price Name Price Name €18.20 B&H Maxi Box 28’s €13.20 Superkings Black €18.20 Silk Cut Blue 28’s €13.20 Superkings Blue €18.20 Silk Cut Purple 28’s €13.20 Superkings Green Menthol €17.00 Marlboro Gold KS Big Box 28s €13.20 Pall Mall 24’s Big Box €16.65 Major 25’s €13.20 JPS Red 24’s €16.40 John Player Blue Big Box 27’s €13.20 JPS Blue 24’s €16.00 Mayfair Superking Original 27’s €13.00 Silk Cut Choice Super Line 20s €16.00 Mayfair Original 27’s €13.00 John Player Blue €16.00 Pall Mall Red 30’s €13.00 John Player Bright Blue €16.00 Pall Mall Blue 30’s €13.00 John Player Blue 100’s €15.50 JPS Blue 29’s €13.00 Lambert & Butler Silver €15.20 Silk Cut Blue 23’s €12.70 B&H Silver 20’s €15.20 Silk Cut Purple 23’s €12.70 B&H Select €15.20 B&H Gold 23’s €12.70 B&H Select 100’s €14.80 John Player Blue Big Box 24’s €12.70 Camel Filters €14.30 Carroll’s Number 1 23 Pack €12.70 Camel Blue €14.20 Mayfair Original 24’s €12.30 Vogue Green €13.70 Players Navy Cut €12.30 Vogue Blue Capsule €13.70 Regal €11.80 Mayfair Double Capsule €13.70 Rothmans €11.80 John Player Blue Compact €13.70 Consulate €11.80 Mayfair Original €13.70 Dunhill International €11.80 Pall Mall Red €13.50 B&H Gold 100’s 20s €11.80 Pall Mall Blue €13.50 Carroll’s No.1 €11.80 Pall Mall Red 100’s €13.50 B&H K.S. -

Young People's Perceptions of Tobacco Packaging

Downloaded from http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on November 14, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com Open Access Research Young people’s perceptions of tobacco packaging: a comparison of EU Tobacco Products Directive & Ireland’s Standardisation of Tobacco Act Kate Babineau, Luke Clancy To cite: Babineau K, ABSTRACT ’ Strengths and limitations of this study Clancy L. Young people s Objectives: To measure young people’s perceptions perceptions of tobacco of tobacco packaging according to two current pieces ▪ ’ packaging: a comparison of This is the first study to compare young people s of legislation: The EU Tobacco Products Directive perceptions of tobacco packs according to EU Tobacco Products ’ Directive & Ireland’s (TPD) and Ireland s Public Health (Standardisation of current regulatory standards established by the Standardisation of Tobacco Tobacco Products) Act. EU Tobacco Products Directive and Ireland’s Act. BMJ Open 2015;5: Design: Within-subject experimental cross-sectional Standardisation of Tobacco Products Act. This e007352. doi:10.1136/ survey of a representative sample of secondary school makes it extremely topical in the on-going public bmjopen-2014-007352 students. School-based pen and paper survey. discussion surrounding these legislative actions. Setting: 27 secondary schools across Ireland, ▪ Draws on a nationwide, representative sample of ▸ Prepublication history and randomly stratified for size, geographic location, young people aged 16–17 in Ireland. additional material is gender, religious affiliation and school-level ▪ Provides applicable, up-to-date evidence on the available. To view please visit socioeconomic status. Data were collected between tobacco packaging debate. the journal (http://dx.doi.org/ March and May 2014. ▪ The study relies on a within-subject design 10.1136/bmjopen-2014- Participants: 1378 fifth year secondary school rather than a between-subject design. -

JTI Response to the UK Department of Health's Consultation on the Future

Response to the UK Department of Health’s Consultation on the Future of Tobacco Control 5 September 2008 Japan Tobacco International is a subsidiary of Japan Tobacco Inc., the world’s third largest global tobacco company. It produces three of the top five worldwide cigarette brands: Winston, Mild Seven and Camel. Other international brands include Benson & Hedges, Silk Cut, Sobranie of London, Glamour and LD. With headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, and net sales of USD 8 billion in the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007, Japan Tobacco International has more than 22,000 employees and operations in 120 countries. Since April 2007, Gallaher Limited (“Gallaher”), the UK-based tobacco products manufacturer, has also formed part of the Japan Tobacco Group. In this response to the FTC Document, we use the term “JTI” to refer collectively to Japan Tobacco International and Gallaher. JTI, which has its UK headquarters in Weybridge, Surrey, has a long-standing, significant presence in the UK market. Its UK cigarette brand portfolio includes Benson & Hedges, Silk Cut, Camel, Mayfair, Sovereign and More, as well as a number of other tobacco products including cigars (such as Hamlet), roll-your-own tobacco and pipe tobacco. JTI manufactures product for the UK market at sites in the UK (in Northern Ireland and Cardiff) and outside it (for example, in Germany). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY JTI agrees with the key policy rationale underlying the Department of Health’s Consultation on the Future of Tobacco Control (the FTC Document): “children and young people” should not smoke, and should not be able to buy tobacco products. -

38 2000 Tobacco Industry Projects—A Listing (173 Pp.) Project “A”: American Tobacco Co. Plan from 1959 to Enlist Professor

38 2000 Tobacco Industry Projects—a Listing (173 pp.) Project “A”: American Tobacco Co. plan from 1959 to enlist Professors Hirsch and Shapiro of NYU’s Institute of Mathematical Science to evaluate “statistical material purporting to show association between smoking and lung cancer.” Hirsch and Shapiro concluded that “such analysis is not feasible because the studies did not employ the methods of mathematical science but represent merely a collection of random data, or counting noses as it were.” Statistical studies of the lung cancer- smoking relation were “utterly meaningless from the mathematical point of view” and that it was “impossible to proceed with a mathematical analysis of the proposition that cigarette smoking is a cause of lung cancer.” AT management concluded that this result was “not surprising” given the “utter paucity of any direct evidence linking smoking with lung canner.”112 Project A: Tobacco Institute plan from 1967 to air three television spots on smoking & health. Continued goal of the Institute to test its ability “to alter public opinion and knowledge of the asserted health hazards of cigarette smoking by using paid print media space.” CEOs in the fall of 1967 had approved the plan, which was supposed to involve “before-and-after opinion surveys on elements of the smoking and health controversy” to measure the impact of TI propaganda on this issue.”113 Spots were apparently refused by the networks in 1970, so plan shifted to Project B. Project A-040: Brown and Williamson effort from 1972 to 114 Project AA: Secret RJR effort from 1982-84 to find out how to improve “the RJR share of market among young adult women.” Appeal would 112 Janet C. -

The Illicit Tobacco Trade Review 2013 JTI Position on the Illegal Trade of Tobacco Contents

The illicit tobacco trade review 2013 JTI POSITION ON THE ILLEGAL TRADE OF TOBACCO CONTENTS The fight against the illegal tobacco trade 01 Introduction 2 05 Why the illegal tobacco trade Government actions - is an important business priority for JTI John Freda, JTI Ireland General Manager has potential to grow 17 against the illegal tobacco trade 31 Ireland. Success against this trade requires Current economic climate 19 - An Garda Síochána ‘Operation Decipher’ cooperation between government and 02 Executive summary 4 - Revenue Customs Service Multi-Annual Consumer downtrading 19 the industry, something JTI Ireland is fully Strategy committed to. 03 Our company at a glance 6 Legislation as a driver of the illegal trade 20 - Department of Social Protection - Revised EU Tobacco Products Directive - Oireachtas Committee on Jobs, 04 Why the illegal tobacco market The potential impact of the proposal Enterprise and Innovation exists 9 to introduce plain packaging 21 JTI actions - International growth 10 No credible evidence 22 against the illegal tobacco trade 32 The scale of illegal tobacco in Ireland 12 Negative effect on the retail trade 22 - Assisting Law Enforcement - Empty Pack Survey (EPS) - All Ireland Illicit Tobacco Trade Bulletin Increasing the illegal trade 23 Drivers of the illegal tobacco trade - Anti Illicit Trade Manager in Ireland A worrying precedent 24 in Ireland 12 - Codentify - High Taxation Alternative solutions 25 Potential solutions to the illegal tobacco - Highly Regulated Market Views on the plain packaging proposal -

TNCO Levels and Ratio's

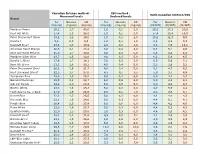

Canadian Intense method - ISO method - Ratio Canadian Intense/ISO Measured levels Declared levels Brand Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) Marlboro Prime 26,1 1,7 40,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 26,1 17,2 20,0 Kent HD White 17,4 1,3 28,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 17,4 13,4 14,0 Peter Stuyvesant Silver 15,2 1,2 19,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 15,2 12,3 9,5 Karelia I 9,6 0,9 9,3 1,0 0,1 1,0 9,6 8,6 9,3 Davidoff Blue* 23,6 1,7 30,9 2,9 0,2 2,6 8,3 7,0 12,1 American Spirit Orange 20,5 2,1 18,4 3,0 0,4 4,0 6,8 5,1 4,6 Kent Surround Menthol 25,0 1,7 30,8 4,0 0,4 5,0 6,3 4,3 6,2 Marlboro Silver Blue 24,7 1,5 32,6 4,0 0,3 5,0 6,2 5,0 6,5 Karelia L (Blue) 17,6 1,7 14,1 3,0 0,3 2,0 5,9 5,6 7,1 Kent HD Silver 21,1 1,6 26,2 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,3 3,9 5,2 Peter Stuyvesant Blue* 20,2 1,6 21,7 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,1 4,7 4,3 Kent Surround Silver* 22,5 1,7 27,0 4,5 0,5 5,5 5,0 3,7 4,9 Templeton Blue 25,0 1,8 26,2 5,0 0,4 6,0 5,0 4,4 4,4 Belinda Filterkings 29,9 2,2 24,7 6,0 0,5 6,0 5,0 4,3 4,1 Silk Cut Purple 24,9 2,0 23,4 5,0 0,5 5,0 5,0 4,0 4,7 Boston White 23,3 1,6 25,3 5,0 0,3 6,0 4,7 5,5 4,2 Mark Adams No. -

Taryield Brand Nicotine Yield CO Yield 1 SILK CUT SILVER KING SIZE 0.1 1 1 MAYFAIR FINE 0.1

file:///J|/eattree/special_licence/6737/mrdoc/pdf/code_frames/cig09.txt UK Data Archive Study Number SN 6716 - General Lifestyle Survey: Secure Access TarYield Brand Nicotine Yield CO Yield 1 SILK CUT SILVER KING SIZE 0.1 1 1 MAYFAIR FINE 0.1 1 2 LAMBERT & BUTLER WHITE 0.2 1 3 MARLBORO KING SIZE (SILVER) 0.3 3 3 SILK CUT BLUE KING SIZE 0.3 3 3 SUPERKINGS WHITE 0.4 3 4 SILK CUT MENTHOL KING SIZE 0.4 5 5 PALL MALL ORANGE 0.5 5 5 RICHMOND KING SIZE MENTHOL 0.4 5 5 LAMBERT & BUTLER GOLD 0.4 5 5 LAMBERT & BUTLER MENTHOL 0.5 5 5 RICHMOND SMOOTH KING SIZE 0.4 6 5 SILK CUT PURPLE KING SIZE 0.5 5 5 JPS KING SIZE WHITE 0.5 6 5 SILK CUT 100S 0.5 6 5 MAYFAIR MENTHOL KING SIZE 0.6 6 5 SUPREME SUPERKINGS WHITE 0.5 5 5 MAXIM SUPERKINGS GOLD 0.5 5 5 BALMORAL SUPERKINGS BLUE 0.5 5 6 LONDIS SUPERKINGS WHITES 0.5 6 6 MARLBORO KING SIZE (GOLD) 0.5 6 6 PARK ROAD SUPERKINGS BLUE 0.6 6 6 NATURAL AMERICAN SPIRIT (YELLOW) 0.7 6 6 SKY WHITE SUPERKINGS 0.5 5 6 JPS KING SIZE GREEN 0.5 6 6 WARWICK SUPERKINGS WHITE 0.5 5 6 BALMORAL KING SIZE BLUE 0.5 7 6 WINSTON BLUE KING SIZE 0.5 7 6 SILK CUT SUPER SLIM 0.7 5 6 MARLBORO MENTHOL KING SIZE 0.5 7 6 CAMEL BLUE 0.5 7 6 JPS KING SIZE SILVER 0.5 7 6 SILK CUT SLIMS PURPLE 0.6 7 6 ROTHMANS ROYALS KING SIZE (BLUE) 0.6 6 6 DORCHESTER SUPERKINGS SMOOTH 0.6 7 6 RED BAND SUPERKINGS WHITE 0.5 6 6 SILK CUT SUPER SLIM MENTHOL 0.7 5 6 DORCHESTER SUPERKINGS MENTHOL 0.6 6 6 WINDSOR BLUE KING SIZE SMOOTH 0.5 7 6 RONSON SUPERKINGS SMOOTH 0.6 7 6 DAVIDOFF GOLD 0.6 6 file:///J|/eattree/special_licence/6737/mrdoc/pdf/code_frames/cig09.txt -

Cigarette Stick As Valuable Communicative Real Estate

Brief report Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053148 on 16 August 2016. Downloaded from Cigarette stick as valuable communicative real estate: a content analysis of cigarettes from 14 low-income and middle-income countries Katherine C Smith,1,2 Carmen Washington,2 Kevin Welding,2 Laura Kroart,2 Adami Osho,2 Joanna E Cohen1,2 1Department of Health, Behavior ABSTRACT cigarette packaging are associated with increased and Society, Johns Hopkins Background The current cigarette market is heavily sales and also influence sensory perceptions around Bloomberg School of Public cigarettes in ways that are key to smoking behav- Health, Baltimore, Maryland, focused on low-income and middle-income countries. USA Branding of tobacco products is key to establishing and iour and addiction. 2Institute for Global Tobacco maintaining a customer base. Greater restrictions on The communicative potential of the product Control, Johns Hopkins marketing and advertising of tobacco products create an itself is considerable; Hammond5 estimated that a Bloomberg School of Public incentive for companies to focus more on branding via pack-a-day smoker would be exposed to a tobacco Health, Baltimore, Maryland, ∼ USA the product itself. We consider how tobacco sticks are pack 7000 times per year. Following this logic, used for communicative purposes in 14 low-income and using a conservative estimate of 10 puffs per cigar- Correspondence to middle-income countries with extensive tobacco markets. ette, the same pack-a-day (20 cigarettes) smoker Dr Katherine Clegg Smith, Methods In 2013, we collected and coded 3232 would encounter a cigarette ∼70 000 times per Department of Health, Behavior cigarette and kretek packs that were purchased from year. -

Drug and Alcohol Dependence First Cigarette on Waking and Time of Day As Predictors of Puffing Behaviour in UK Adult Smokers

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 101 (2009) 191–195 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Drug and Alcohol Dependence journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugalcdep First cigarette on waking and time of day as predictors of puffing behaviour in UK adult smokers Matthew J. Grainge a,∗, Lion Shahab b, David Hammond c, Richard J. O’Connor d, Ann McNeill a a Division of Epidemiology & Public Health, University of Nottingham, UK b Department of Epidemiology & Public Health, University College London, UK c Department of Health Studies & Gerontology, University of Waterloo, Canada d Department of Health Behavior, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, USA article info abstract Article history: Background: There is known inter- and intra-individual variation in how cigarettes are smoked. The aim Received 4 September 2008 of this study was to explore the influence of diurnal factors, particularly the first cigarette of the day, on Received in revised form 17 December 2008 puffing behaviour in a sample of adult smokers. Accepted 12 January 2009 Methods: We recruited 130 adults aged 18–60 years who were smoking one of seven cigarette brands pop- Available online 4 March 2009 ular in the UK. Puffing behaviour was measured using a portable smoking device (CReSSmicro) through which participants smoked their cigarettes over a 24 h study period. The primary outcome was total Keywords: smoke volume per cigarette (obtained by summing the puff volumes for each cigarette). Secondary out- Puffing behaviour Smoking deprivation come measures were puffing frequency, average puff volume, average puff flow, average puff duration Diurnal effects and inter-puff interval. Results: Total smoke volume was found to be significantly associated with the time the cigarette was smoked (P < 0.001), with cigarettes smoked between 2 and 10 a.m. -

JTI UK's Response to Tobacco and Related Products Regulation And

Consultation on the Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 and the Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations 2015 Response submitted on behalf of JTI UK 19 March 2021 About JTI Japan Tobacco International (JTI) is part of the Japan Tobacco group of companies, a leading international tobacco and e-cigarette manufacturer. JTI has its UK headquarters in Weybridge, Surrey, and has a long-standing and significant presence in the UK, with a national distribution centre in Crewe and a nationwide field-based Sales force. Its brand portfolio includes Benson & Hedges, Silk Cut, Mayfair, Sovereign and Sterling, as well as a number of other tobacco products including roll-your-own tobacco (RYO), also known as hand-rolling tobacco (such as Amber Leaf), cigars (such as Hamlet) and pipe tobacco (such as Condor). JTI sells nicotine pouches under its brand, Nordic Spirit. JTI is also a major player in reduced risk products with its brand, Logic, and heated tobacco brand, Ploom. JTI’s UK excise contributions on its tobacco products amounted to around £5.5 billion in 2020. The Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 Question 1: How far do you agree or disagree that the introduction of rotating combined (photo and text) health warnings on cigarette and hand rolling tobacco has encouraged smokers to quit? • Strongly agree • Agree • Neither agree or disagree • Disagree • Strongly disagree • Don’t know There is no credible evidence to suggest that the introduction of rotating combined (photo and text) health warnings on cigarettes and hand rolling tobacco has encouraged smokers to quit. Smoking rates were already in decline well before the introduction of such regulations with the most recent Smoking Toolkit Study showing that an estimated 14.8% of adults smoked in 2020, compared with a rate of 21.4% in 2010 and 18.0% in 2016 (1). -

2017 Results & 2018 Forecast Supplemental

Financial Results Supplemental Material FY2017 Fourth Quarter [This slide intentionally left blank] Data Sheets Terms Definitions Operating profit + amortization cost of acquired intangibles arising from business acquisitions + adjusted items (income and costs)* Adjusted Operating Profit *Adjusted items (income and costs) = impairment losses on goodwill ± restructuring income and costs ± others Consolidated Adjusted For International Tobacco Business, the same foreign exchange rates between local Operating Profit currencies vs USD and JPY vs USD as same period in previous fiscal year are applied at Constant FX Total Shipment Volume Includes fine cut, cigars, pipe tobacco, snus and kretek but excludes contract (International Tobacco Business) manufactured products, waterpipe tobacco, and Reduced-Risk Products Core Revenue Includes revenue from waterpipe tobacco and Reduced-Risk Products, but excludes (International Tobacco Business) revenues from distribution, contract manufacturing and other peripheral businesses Core Revenue/ Adjusted Operating Profit The same foreign exchange rates between local currencies vs USD as same period in at Constant FX previous fiscal year are applied (International Tobacco Busines) Includes revenue from domestic duty free, the China business and Reduced-Risk Core Revenue Products such as Ploom TECH devices and capsules but excludes revenue from (Japanese Domestic Tobacco distribution of imported tobacco in the Japanese domestic tobacco business, among Business) others Japanese Domestic Tobacco Industry Volume -

Customs and Tobacco Report 2010

Publisher Date of publication [World Customs Organization [June 2011 Customs and Tobacco Report Rue du marché 30 [ B-1210 Brussels Belgium 2010 Tel. : +32 (0)2 209 92 11 Fax. : +32 (0)2 209 92 92 E-mail : [email protected] Web site : http://www.wcoomd.org Rights and permissions Copyright © 2011 World Customs Organization. All rights reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning translation, reproduction and adaptation rights should be addressed to [email protected]. D/2011/0448/7 WORLD CUSTOMS ORGANIZATION For official use only Foreword FOREWORD whether, laws are flouted, consumers’ health gling of smaller consignments showed a sig - is damaged, governments lose revenues, or nificant increase. This is partially explained legitimate businesses lose trade. by some Members not having filed finalized reports at the date of publishing, improved We have witnessed an unparalleled growth anti smuggling techniques and the introduc - in illicit trade of tobacco products over tion of stricter measures in some countries recent years and we need to step up our such as, increased penalties, and enhanced I am pleased to present the ninth issue of efforts to tackle this problem. The present seizure or confiscation provisions in relation the WCO’s Customs and Tobacco report. report makes very clear that Customs to vehicles and personal assets. This annual publication correlates and administrations worldwide are committed to rising to meet this challenge. analyses the information provided by Specific patterns of the illicit trade in tobacco Members in relation to the worldwide trade products vary from region to region. One The substantive content of the 2010 report in illicit tobacco products.