Does This Mean the FBI Is After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Fourth Amendment Ramifications of Stingray Devices

SEVENTH CIRCUIT REVIEW Volume 12, Issue 2 Spring 2017 WHO’S PINGING YOUR PHONE? EXPLORING THE FOURTH AMENDMENT RAMIFICATIONS OF STINGRAY DEVICES Cite as: Karen Vaysman, Who’s Pinging Your Phone? Exploring the Fourth Amendment Ramifications of Stingray Devices, 12 SEVENTH CIRCUIT REV. 365 (2017), at www.kentlaw.iit.edu/Documents/Academic Programs/7CR/12-1/ vaysman.pdf. KAREN VAYSMAN INTRODUCTION In 2001, the Supreme Court in Kyllo v. United States profoundly declared that “[i]t would be foolish to contend that the degree of privacy secured to citizens by the Fourth Amendment has been entirely unaffected by the advance of technology.”1 No less true is this statement today than when it was made, sixteen years ago, at a time when smartphones of the kind that exist today were unheard of to the Court. The modern smartphone device possesses unprecedented capabilities. With its massive storage capacity and ability to collect, all in one place distinct types of information, the phone can reconstruct an individual’s private life, all in the palm of a hand.2 Technological progress has a dual capability to decrease privacy, yet simultaneously augment the expectation of privacy. As cellphones become more sophisticated, so too does police surveillance. With J.D. candidate, May 2017, Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology; B.S., Communications, University of Miami, 2014. 1 Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27, 33–34 (2001). 2 Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 2489 (2014). 365 SEVENTH CIRCUIT REVIEW Volume 12, Issue 2 Spring -

A Lot More Than a Pen Register, and Less Than a Wiretap

Pell and Soghoian: A Lot More than a Pen Register, and Less than a Wiretap 1 A LOT MORE THAN A PEN REGISTER, AND LESS THAN A WIRETAP: WHAT THE STINGRAY TEACHES US ABOUT HOW CONGRESS SHOULD APPROACH THE REFORM OF LAW ENFORCEMENT SURVEILLANCE 2 AUTHORITIES Stephanie K. Pell* & Christopher Soghoian** 16 YALE J.L. & TECH. 134 (2013) ABSTRACT In June 2013, through an unauthorized disclosure to the media by ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden, the public learned that the NSA, since 2006, had been collecting nearly all domestic phone call detail records and other telephony metadata pursuant to a controversial, classified interpretation of Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act. Prior to the Snowden disclosure, the existence of this intelligence program had been kept secret from the general public, though some members of Congress knew both of its existence and of the statutory interpretation the government was using to justify the bulk collection. Unfortunately, the classified nature of the Section 215 metadata program prevented them from alerting the public directly, so they were left to convey their criticisms of the program directly to certain federal agencies as part of a non-public oversight process. The efficacy of an oversight regime burdened by such strict secrecy is now the subject of justifiably intense debate. In the context of that debate, this Article examines a very different surveillance technology—one that has been used by federal, state and local law enforcement agencies for more than two decades without invoking even the muted scrutiny Congress applied to the Section 215 metadata program. -

IMSI-Catcher -Wikipedia Visited on 5/04/2018 Page 1 of 6

IMSI-catcher -Wikipedia visited on 5/04/2018 Page 1 of 6 IMSI-catcher An International Mobile Subscriber Identity-catcher, or IMSI-catcher, is a telephone eavesdropping device used for intercepting mobile phone traffic and tracking location data of mobile phone users.[1] Essentially a "fake" mobile tower acting between the target mobile phone and the service provider's real towers, it is considered a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack. The 3G wireless standard has some risk due to mutual authentication required from both the handset and the network.[2] However, sophisticated attacks may be able to downgrade 3G and LTE to non-LTE network services which do not require mutual authentication.[3] IMSI-catchers are used in the United States and other countries by law enforcement and intelligence agencies, but their use has raised significant civil liberty and privacy concerns and is strictly regulated in some countries such as under the German Strafprozessordnung (StPO / Code of Criminal Procedure).[1][4] Some countries do not even have encrypted phone data traffic (or very weak encryption), thus rendering an IMSI-catcher unnecessary. Contents Overview Functionalities Identifying an IMSI Tapping a mobile phone Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) Disclosing facts and difficulties Detection and counter-measures See also Footnotes Further reading External links Overview A virtual base transceiver station (VBTS)[5] is a device for identifying the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) of a nearby GSM mobile phone and intercepting its calls. It was patented[5] and first commercialized by Rohde & Schwarz in 2003. The device can be viewed as simply a modified cell tower with a malicious operator, and on 4 January 2012, the Court of Appeal of England and Wales held that the patent is invalid for obviousness.[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IMSI-catcher 5/4/2018 IMSI-catcher -Wikipedia visited on 5/04/2018 Page 2 of 6 The GSM specification requires the handset to authenticate to the network, but does not require the network to authenticate to the handset. -

Triggerfish, Stingrays, and Fourth Amendment Fishing Expeditions

Owsley_16 (Teixeira corrected).doc (Do Not Delete) 11/26/2014 2:23 PM TriggerFish, StingRays, and Fourth Amendment Fishing Expeditions Brian L. Owsley* Cell site simulators are an electronic surveillance device that mimics a cell tower causing all nearby cell phones to register their data and information with the cell site simulator. Law enforcement increasingly relies on these devices during the course of routine criminal investigations. The use of cell site simulators raises several concerns. First, the federal government seeks judicial authorization to use such devices via a pen register application. This approach is problematic because a cell site simulator is different than a pen register. Moreover, the standard for issuance of a pen register is very low. Instead, this Article proposes that the applicable standard for granting a request to use a cell site simulator should be based on the Fourth Amendment probable cause standard. Second, cell site simulators sweep up the data and information of innocent third-parties. The government fails to account for this problem. This Article proposes that the granting of an application for a cell site simulator should require a protocol for dealing with the third-party information that is captured. * Brian L. Owsley, Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana Tech Law School; B.A., 1988, University of Notre Dame; J.D., 1993, Columbia University School of Law; M.I.A., 1994, Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs. From 2005 until 2013, the Author served as a United States Magistrate Judge for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas. I am very grateful for valuable comments and critiques provided by Steven Friedland, Jonah Horwitz, Stephen Wm. -

The Undue Influence of Surveillance Technology Companies on Policing

JOH-FINAL.DOCX(DO NOT DELETE) 9/17/17 9:20 PM THE UNDUE INFLUENCE OF SURVEILLANCE TECHNOLOGY COMPANIES ON POLICING ELIZABETH E. JOH* Conventional wisdom assumes that the police are in control of their investigative tools. But with surveillance technologies, this is not always the case. Increasingly, police departments are consumers of surveillance technologies that are created, sold, and controlled by private companies. These surveillance technology companies exercise an undue influence over the police today in ways that aren’t widely acknowledged, but that have enormous consequences for civil liberties and police oversight. Three seemingly unrelated examples—stingray cellphone surveillance, body cameras, and big data software—demonstrate varieties of this undue influence. The companies which provide these technologies act out of private self-interest, but their decisions have considerable public impact. The harms of this private influence include the distortion of Fourth Amendment law, the undermining of accountability by design, and the erosion of transparency norms. This Essay demonstrates the increasing degree to which surveillance technology vendors can guide, shape, and limit policing in ways that are not widely recognized. Any vision of increased police accountability today cannot be complete without consideration of the role surveillance technology companies play. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 102 I. EXAMPLES OF UNDUE INFLUENCE ................................................. -

Stingray Phone Tracker - Wikipediavisited on 11/28/2016 Page 1 of 9

Stingray phone tracker - Wikipediavisited on 11/28/2016 Page 1 of 9 Stingray phone tracker From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The StingRay is an IMSI-catcher, a controversial cellular phone surveillance device, manufactured by Harris Corporation.[2] Initially developed for the military and intelligence community, the StingRay and similar Harris devices are in widespread use by local and state law enforcement agencies across the United States[3][4] and possibly covertly in the United Kingdom.[5] Stingray has also become a generic name to describe these kinds of devices.[6] A Stingray device in 2013, in Harris's trademark submission. Contents [1] ◾ 1 Technology ◾ 1.1 Active mode operations ◾ 1.2 Passive mode operations ◾ 1.3 Active (cell site simulator) capabilities ◾ 1.3.1 Extracting data from internal storage ◾ 1.3.2 Writing metadata to internal storage ◾ 1.3.3 Forcing an increase in signal transmission power ◾ 1.3.4 Forcing an abundance of signal transmissions ◾ 1.3.5 Tracking and locating ◾ 1.3.6 Denial of service ◾ 1.3.7 Interception of communications content ◾ 1.4 Passive capabilities ◾ 1.4.1 Base station (cell site) surveys ◾ 2 Usage by law enforcement ◾ 2.1 In the United States ◾ 2.2 Outside the United States ◾ 3 Secrecy ◾ 4 Criticism ◾ 5 Countermeasures ◾ 6 See also ◾ 7 References ◾ 8 Further reading Technology The StingRay is an IMSI-catcher with both passive (digital analyzer) and active (cell site simulator) capabilities. When operating in active mode, the device mimics a wireless carrier cell tower in order to force all nearby mobile phones and other cellular data devices to connect to it.[7][8][9] The StingRay family of devices can be mounted in vehicles,[8] on airplanes, helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles. -

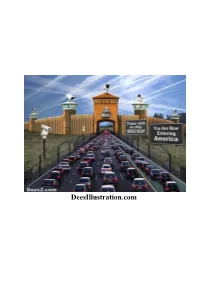

Deesillustration.Com

DeesIllustration.com PART I SURVEILLANCE AND SPYING Heterogenous Aerial Reconnaissance Team program developed by DARPA 23 DeesIllustration.com 24 ONE SURVEILLANCE Technology is being developed to insure Big Brother will know everything each citizen does, says, hears and even thinks. Fantastic surveillance technology has already been developed, and it is being used at present to track where people go, what they do, what they see and hear, and what they say. The Big Brother surveillance web is growing larger every day, and very few are able to keep from being caught in it. Space surveillance Space-based spy cameras are so ubiquitous Big Brother can watch virtually every square inch of the planet around the clock. “Every 10 seconds nearly the entire Earth’s surface is scanned by Defense Support Program (DSP) infrared surveillance satellites looking for the telltale signs of hostile missile launches. The Aerospace Corporation has been investigating the feasibility of using this existing capability to detect natural disasters and other related environmental phenomena.”1 Former Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Chairman Michael Chertoff sought to implement a plan in April of 2008, that allowed domestic law enforcement agencies to use data gathered by spy satellites. DHS planned to create a new office that would expand access by law enforcement and other civilian agencies to data gathered by powerful intelligence satellites orbiting Earth. The National Applications Office will oversee who has access to the data.2 This plan was questioned by Congressman Ed Markey, but not stopped.3 Several agencies have access to satellites cameras capable of reading newsprint. -

The Brave New World of Cell-Site Simulators

DO NOT DELETE 2/6/2015 3:18 PM THE BRAVE NEW WORLD OF CELL-SITE SIMULATORS Heath Hardman INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 3 I. PUBLIC AWARENESS ...................................................................... 3 A. Cell-Site Simulators in the Media .................................... 3 B. United States v. Rigmaiden .............................................. 8 GRAPHIC 1: STINGRAY ..................................................................... 11 II. PRIMER ON CELLULAR TECHNOLOGY ........................................ 12 A. Cell Selection .................................................................... 12 B. Location Updating ........................................................... 14 C. Paging & Calls ................................................................. 15 III. POSSIBLE METHODS OF LOCATING A CELLPHONE WITH A CELL-SITE SIMULATOR ......................................................... 17 A. Gather Historical Location Data ................................... 17 GRAPHIC 2: CELL-SITE, SECTOR, AND TIMING ADVANCE ............... 18 B. Simulate a Cell-Site and Attract the Target Cellphone ........................................................................ 18 C. Page the Target Cellphone ............................................. 19 D. Locate the Target Cellphone .......................................... 19 GRAPHIC 3: POSITION AND DIRECTION OVERLAID ON MAP ........... 20 IV. LEGAL IMPLICATIONS AND ISSUES ........................................... -

First Amendment Lawyer's Association Recent Ethical

FIRST AMENDMENT LAWYER’S ASSOCIATION QUÉBEC, QC, CANADA CONFERENCE 2019 RECENT ETHICAL ISSUES IN THE PRACTICE OF LAW BARRY NELSON COVERT, ESQ. LIPSITZ GREEN SCIME CAMBRIA LLP 42 DELAWARE AVENUE, SUITE 120, BUFFALO, NEW YORK 14202 (716) 849-1333 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Ethics of Joint Defense Agreements II. Jury Selection in the Trump Era – “Fake News” and the Corrupt FBI!!! III. Opening Arguments – Never Concede, Surrender or Back Down IV. The Government’s Direct Proof V. “Just Say No” VI. Handling a Claim of Ineffective Assistance V12 IX.Your Legal Advice Can Get You Indicted 29 XI.Ethics and Litigation XII. First Amendment Right to Record the Police...................................................34 XIII. Post Snowden Electronic Confidentiality- Beware the Invasion of “Bots” and “Malware”.....................................................................................................38 XIV. Identifying and Handling Conflicts of Interest XV. No Need to Attend the Entire Trial?..................................................................62 XVI. Fraud Behind the ‘Legal Curtain’......................................................................... XVII. Client Relations XVIII. Types of Prosecutorial Misconduct...................................................................69 1 I. The Ethics of Joint Defense Agreements A. Joint Defense Agreements and the Monolithic Defense 22 NYCRR 1200.1 Rule 1.1 states that: “A lawyer should provide competent representation to a client. Competent representation requires legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness, and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation.” Joint Defense Agreements (“JDA”) and multiple defendant trials create unique and vexing problems including relationship dynamics among co- defendants and co-counsel, as well as zealously representing your client’s best interests without harming a co-defendant. The goal of all counsel must be to uniformly challenge and undermine the government’s Theory of Prosecution. A monolithic defense. -

Criminal Law, National Security, and Privacy

INF529: Security and Privacy In Informatics Criminal law, National Security, and Privacy Prof. Clifford Neuman Lecture 10 22 March 2019 OHE 100C Course Outline • What data is out there and how is it used • Technical means of protection • Identification, Authentication, Audit • The right of or expectation of privacy • Government and Policing access to data – February15th • Mid-term, Then more on Government, Politics, and Privacy • Social Networks and the social contract – March 1st • Big data – Privacy Considerations – March 8th • Criminal law, National Security, and Privacy – March 22nd • Civil law and privacy – March 29th (also Measuring Privacy) • International law and conflict across jurisdictions – April 5th • The Internet of Things – April 12th • Technology – April 19th • The future – What can we do – April 26th Homework 2: Big Data, Due 25 March Consider the articles that have been assigned as readings in the past three weeks (from the website, and from the lecture slides). Based on these readings, and discussions in class, please answer the following question. Explain how machine learning, data mining, and statistical inference methods can use “big data” about us in ways that are against our personal well-being. How can these techniques uncover (or discover) possibly incorrect information, and how do they create or reinforce profiles and stereotypes that society has long sought to abolish. Your answer should be roughly four pages in length ( about 1600 to 2000 words), but this is not a strict limit. Please submit your answers before -

Rigmaiden-Amici-Fina

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF ARIZONA United States of America, | No. CR08-814-PHX-DGC Plaintiff | v. | Daniel David Rigmaiden, et al., | Defendant. | | ___________________________________ | BRIEF OF RESEARCHERS AND EXPERTS, PRO SE, AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT’S MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE OF ALL RELEVANT AND HELPFUL EVIDENCE WITHHELD BY THE GOVERNMENT BASED ON A CLAIM OF PRIVILEGE Table of Contents STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ........................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 2 IMSI CATCHERS HAVE BEEN SOLD BY COMMERCIAL SURVEILLANCE VENDORS FOR MORE THAN FIFTEEN YEARS ......................................................................................................... 3 SURVEILLANCE VENDORS PROUDLY ADVERTISE THEIR IMSI CATCHERS AND DESCRIBE THEIR FEATURES IN PUBLIC MARKETING MATERIALS ..................................... 4 A SUBSTANTIAL AMOUNT OF DETAILED TECHNICAL INFORMATION ABOUT IMSI CATCHERS IS ALREADY PUBLIC ................................................................................................... 7 IMSI CATCHERS CAN NOW BE BUILT FOR $1500 USING PUBLICLY AVAILABLE SOFTWARE .......................................................................................................................................... -

Big Brother Is Watching You

BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU By F. Kenton Beshore and R. William Keller World Bible Society Costa Mesa, California Big Brother Is Watching You Copyright 2011 by F. Kenton Beshore and R. William Keller Published by World Bible Society P.O. Box 5000, Costa Mesa, California 92628 Book I, First Edition, December 2011 Printed in the United States of America ISBN – 978-0-615-45545-7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise – without prior written permission of the authors, except as provided by USA copyright law. All Scripture quotations are from the American Standard Version unless otherwise noted. For information about the ministry of Dr. Beshore and the World Bible Society, visit our web site: www.worldbible.com. 2 Dedication We dedicate this book to our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ for His infallible holy Word which gives us the Blessed Hope of His return that all students of Bible prophecy eagerly look forward to by watching for the warning signs that precede it. One of those warning signs is the rise of Big Brother. 3 Acknowledgments We acknowledge the tireless efforts of Alex Jones of PrisonPlanet.com PrisonPlanet.tv and InfoWars.com – the leading researcher and filmmaker exposing the machinations of Big Brother not only in America, but the entire planet. Jones is correct that Big Brother is turning Earth into a prison planet and this book documents that fact. We also acknowledge the excellent work of other researchers, past and present, who have committed their lives to exposing the machinations of Big Brother – Eric Blair, Gary Allen, James Bamford, David Bay, John Beaty, Michael Benson, Lenn Bracken, Ray Bradbury, William Guy Carr, Count Cherep-Spiridovich, John Coleman, Jerome Corsi, Dennis Cuddy, Bill Deagle, David Dees, Stan Deyo, Mark Dice, James Drummey, Daniel Estulin, Robert Eringer, Myron Fagan, Philip Gardiner, John Gatto, David Ray Griffin, Des Griffin, G.