Perisoreus Infaustus, L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walker Marzluff 2017 Recreation Changes Lanscape Use of Corvids

Recreation changes the use of a wild landscape by corvids Author(s): Lauren E. Walker and John M. Marzluff Source: The Condor, 117(2):262-283. Published By: Cooper Ornithological Society https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Volume 117, 2015, pp. 262–283 DOI: 10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Recreation changes the use of a wild landscape by corvids Lauren E. Walker* and John M. Marzluff College of the Environment, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted October 24, 2014; Accepted February 13, 2015; Published May 6, 2015 ABSTRACT As urban areas have grown in population, use of nearby natural areas for outdoor recreation has also increased, potentially influencing bird distribution in landscapes managed for conservation. -

Corvids of Cañada

!!! ! CORVIDS OF CAÑADA COMMON RAVEN (Corvus corax) AMERICAN CROW (Corvus brachyrhyncos) YELLOW-BILLED MAGPIE (Pica nuttalli) STELLER’S JAY (Cyanocitta stelleri) WESTERN SCRUB-JAY Aphelocoma californica) Five of the ten California birds in the Family Corvidae are represented here at the Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve. Page 1 The Common Raven is the largest and can be found in the cold of the Arctic and the extreme heat of Death Valley. It has shown itself to be one of the most intelligent of all birds. It is a supreme predator and scavenger, quite sociable at certain times of the year and a devoted partner and parent with its mate. The American Crow is black, like the Raven, but noticeably smaller. Particularly in the fall, it may occur in huge foraging or roosting flocks. Crows can be a problem for farmers at times of the year and a best friend at other times, when crops are under attack from insects or when those insects are hiding in dried up leftovers such as mummified almonds. Crows know where those destructive navel orange worms are. Smaller birds do their best to harass crows because they recognize the threat they are to their eggs and young. Crows, ravens and magpies are important members of the highway clean-up crew when it comes to roadkills. The very attractive Yellow-billed Magpie tends to nest in loose colonies and forms larger flocks in late summer or fall. In the central valley of California, they can be a problem in almond and fruit orchards, but they also are adept at catching harmful insect pests. -

Finland - Easter on the Arctic Circle

Finland - Easter on the Arctic Circle Naturetrek Tour Report 14 - 18 April 2017 Bohemian Waxwing by Martin Rutz Siberian Jay by Martin Rutz Willow Tit by Martin Rutz Boreal (Tengmalm’s) Owl by Martin Rutz Report compiled by Alice Tribe Images courtesy of Martin Rutz & Alice Tribe Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Finland - Easter on the Arctic Circle Tour participants: Ari Latja & Alice Tribe (leaders) with fourteen Naturetrek clients Day 1 Friday 14th April London to Oulu After a very early morning flight from Heathrow to Helsinki, we landed with a few hours to spend in the airport. It was here that most of the group met up, had lunch and used the facilities, with all of us being rather impressed by the choice of music in the lavatories: bird song! A few members of the group commented on the fact that there was no snow outside, which was the expected sight. It was soon time for us to board our next flight to Oulu, a journey of only one hour, but during the flight the snow levels quickly built up on the ground below us. We landed around 5pm and met a few more of our group at baggage reclaim. Once everyone had collected their luggage, we exited into the Arrivals Hall where our local guide Ari was waiting to greet us. Ari and Alice then collected our vehicles and once everyone was on board, we headed to Oulu’s Finlandia Airport Hotel, our base for the next two nights, which was literally ‘just down the road’ from Oulu Airport. -

Pinyon Jay Movement, Nest Site Selection, Nest Fate

PINYON JAY MOVEMENT, NEST SITE SELECTION, NEST FATE, AND RENESTING IN CENTRAL NEW MEXICO By MICHAEL COULTER NOVAK Bachelor of Science in Zoology University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 2019 PINYON JAY MOVEMENT, NEST SITE SELECTION, NEST FATE, AND RENESTING IN CENTRAL NEW MEXICO Thesis Approved: Dr. Loren M. Smith Thesis Adviser Dr. Scott T. McMurry Dr. Craig A. Davis ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank my advisor, Dr. Loren Smith, for his expert assistance guiding me through my thesis. Through his mentorship I learned to be a more effective writer and scientist. Thank you to my committee members, Dr. Scott McMurry and Dr. Craig Davis, for their valuable input on my research. Much thanks to Oklahoma State University for providing excellent academic resources and being a great place to develop professional skills required for today’s workforce. I want to thank my parents, Michael Novak and Kathleen Murphy, who have always encouraged me to work hard and be happy. I’m especially grateful for their understanding and encouragement throughout my transient career as a seasonal field biologist. Thanks, Dad, for encouraging me to find a job where they pay me to travel. Thanks, Mom, for encouraging me to pursue higher education and for keeping me on track. Thanks to my sister, Marisol Novak, for her siblingship and being a willing ear to vent my problems to. My family has always believed in me and they inspire me to continue putting one foot in front of the other, even when things are difficult. -

Inner Mongolia Cumulative Bird List Column A

China: Inner Mongolia Cumulative Bird List Column A: total number of days that the species was recorded in 2016 Column B: maximum daily count for that particular species Column C: H = Heard only; (H) = Heard more often than seen Globally threatened species as defined by BirdLife International (2004) Threatened birds of the world 2004 CD-Rom Cambridge, U.K. BirdLife International are identified as follows: EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; NT = Near- threatened. A B C Ruddy Shelduck 2 3 Tadorna ferruginea Mandarin Duck 1 10 Aix galericulata Gadwall 2 12 Anas strepera Falcated Teal 1 4 Anas falcata Eurasian Wigeon 1 2 Anas penelope Mallard 5 40 Anas platyrhynchos Eastern Spot-billed Duck 3 12 Anas zonorhyncha Eurasian Teal 2 12 Anas crecca Baer's Pochard EN 1 4 Aythya baeri Ferruginous Pochard NT 3 49 Aythya nyroca Tufted Duck 1 1 Aythya fuligula Common Goldeneye 2 7 Bucephala clangula Hazel Grouse 4 14 Tetrastes bonasia Daurian Partridge 1 5 Perdix dauurica Brown Eared Pheasant VU 2 15 Crossoptilon mantchuricum Common Pheasant 8 10 Phasianus colchicus Little Grebe 4 60 Tachybaptus ruficollis Great Crested Grebe 3 15 Podiceps cristatus Eurasian Bittern 3 1 Botaurus stellaris Yellow Bittern 1 1 H Ixobrychus sinensis Black-crowned Night Heron 3 2 Nycticorax nycticorax Chinese Pond Heron 1 1 Ardeola bacchus Grey Heron 3 5 Ardea cinerea Great Egret 1 1 Ardea alba Little Egret 2 8 Egretta garzetta Great Cormorant 1 20 Phalacrocorax carbo Western Osprey 2 1 Pandion haliaetus Black-winged Kite 2 1 Elanus caeruleus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7, As Amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7, as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. Note for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Bureau. Compilers are strongly urged to provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of maps. FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Designation date Site Reference Number 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: Timo Asanti & Pekka Rusanen, Finnish Environment Institute, Nature Division, PO Box 140, FIN-00251 Helsinki, Finland. [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: January 2005 3. Country: Finland 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Koitelainen Mires 5. Map of site included: Refer to Annex III of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines, for detailed guidance on provision of suitable maps. a) hard copy (required for inclusion of site in the Ramsar List): Yes. b) digital (electronic) format (optional): Yes. 6. Geographical coordinates (latitude/longitude): 67º46' N / 27º10' E 7. General location: Include in which part of the country and which large administrative region(s), and the location of the nearest large town. The unbroken area is situated in central part of the province of Lapland, in the municipality of Sodankylä, 40 km northeast of Sodankylä village. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

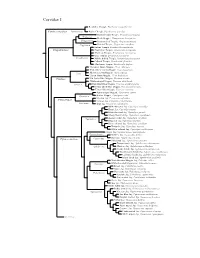

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Mate-Guarding in Siberian Jay (Perisoreus Infaustus)

Mate-guarding in Siberian jay (Perisoreus infaustus) Mate-guarding hos Lavskrikor (Perisoreus infaustus) Leo Ruth Faculty of Health, Science and Technology Biology Independent Research Project 15 hp Supervisor: Björn Arvidsson and Michael Griesser Examinor: Larry Greenberg 26/08-16 Serial number: 16:102 Abstract Mate-guarding is performed by many monogamous species, a method used by individuals to physically prevent competitors of the same sex from mating with their partners. This behaviour is most often displayed during the fertile period (i.e. when females can be fertilized). In this study I focused on the genetically and socially monogamous species, the Siberian jay (Perisoreus infaustus), in which I observed mate-guarding behaviour. The Siberian jays did change their behaviour and increased their aggression in the fertile period, a sign of mate-guarding. This result also suggests that even socially and genetically monogamous species do increase their aggression during the fertile period. This indicates that fidelity still requires an investment in mate-guarding to limit extra-pair mating opportunities. Mate- guarding should then be possible to find in species where there is at least a theoretical opportunity for extra-pair matings. Sammanfattning Mate-guarding är en metod använd utav många monogama arter, metoden används för att fysiskt hålla konkurrenter utav samma kön borta ifrån sin partner för att försäkra sin egen parning. Denna metod beskådas oftast under tiden honan är fertil. I denna studie fokuserade jag på den genetiska och sociala monogama arten Lavskrika(Perisoreus infaustus) där jag observerade mate-guarding beteende. Lavskrikans beteende förändrades mellan perioden då honan icke var receptiv och hon var fertil, aggressionen ökade för båda könen under den fertila perioden vilket är ett tecken utav mate-guarding beteende. -

Studies of Less Familiar Birds 162 Siberian Jay Arne Blomgren Photographs by Arne Blomgren and J

Studies of less familiar birds 162 Siberian Jay Arne Blomgren Photographs by Arne Blomgren and J. B. and S. Bottomley Plates 1-8 The Siberian Jay Perisoreus infaustus is a bird of the great belt of coniferous forest which stretches from Scandinavia east through northern Russia and right across Siberia. It breeds in Norway, Sweden and Finland from Lapland south roughly to 61°N (Lovenskiold 1947, Curry-Lindahl 1963, Merikallio 1958) with only occasional wanderings south of this line to the level of southern Norway, but in the Soviet Union it follows the more southerly spread of the conifers (Dementiev and Gladkov 1951-54). In European Russia it extends down to the region of Moscow and the southern Urals, and in Asia it breeds south to the Altai, northern Mongolia and probably north-east Manchuria, east to Anadyr, the Sea of Okhotsk, Sakhalin and Ussuriland (Vaurie 1959). In the north it nests up to the conifer limit and also occurs in areas of mountain birch Be tula tortuosa where Ekmau (1944) said that it was not known to breed, though Blair (1936) found it 'nesting in both birch woods and pine forests' in the Syd Varanger. Most records from the birch are probably casual visitors from the conifers near-by. It is replaced in the mountains of China from central Sinkiang to northern Szechwan by the related Szechwan Grey Jay P. internigrans (Vaurie 1959), while a third species, the Canada Jay P. canadensis, occupies similar conifer habitats in North America from Alaska, Mackenzie and Labrador south to Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico, Minnesota and northern New York (Bent 1946). -

The Common Magpie, Pica Pica

The complexity of neophobia in a generalist foraging corvid: the common magpie, Pica pica Submitted by Toni Vernelli to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology April 2013 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all the material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university. Signature: __Toni Vernelli_________ 1 ABSTRACT It is often suggested that species differences in neophobia are related to differences in feeding or habitat specialisation. Generalist species, which have more to gain from exploring novel resources, tend to be less neophobic than specialists. However, some successful generalists including ravens, brown rats and coyotes also demonstrate high levels of neophobia. I explored this paradox using common magpies, a widespread generalist opportunist that displays behaviour indicative of high neophobia. Using a combination of field and short- term captive studies, I investigated whether novelty reactions were a fixed trait or varied according to object features and context as well as for different categories of novelty (i.e. objects, food, location). I found that novelty reactions in magpies were not influenced by object features such as colour, shape or size but varied greatly depending on environmental context and novelty category. Birds did not show avoidance of novel objects presented in novel environments but were extremely wary of similar novel objects presented in familiar environments, suggesting that violation of expectations may be more important than absolute novelty. -

Pellet-Casting by a Western Scrub-Jay Mary J

NOTES PELLET-CASTING BY A WESTERN SCRUB-JAY MARY J. ELPERS, Starr Ranch Bird Observatory, 100 Bell Canyon Rd., Trabuco Canyon, California 92679 (current address: 3920 Kentwood Ct., Reno, Nevada 89503); [email protected] JEFF B. KNIGHT, State of Nevada Department of Agriculture, Insect Survey and Identification, 350 Capitol Hill Ave., Reno, Nevada 89502 Pellet casting in birds of prey, particularly owls, is widely known. It is less well known that a wide array of avian species casts pellets, especially when their diets contain large amounts of arthropod exoskeletons or vertebrate bones. Currently pellet casting has been documented for some 330 species in more than 60 families (Tucker 1944, Glue 1985). Among the passerines reported to cast pellets are eight species of corvids: the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) (Lamore 1958, Tarvin and Woolfenden 1999), Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) (Balda 2002), Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) (Strickland and Ouellet 1993), Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) (Trost 1999), Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nuttalli) (Reynolds 1995), American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) (Verbeek and Caffrey 2002), Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) (Butler 1974), and Common Raven (Corvus corax) (Temple 1974, Harlow et al. 1975, Stiehl and Trautwein 1991, Boarman and Heinrich 1999). However, the behavior has not been recorded in the four species of Aphelocoma jays (Curry et al. 2002, Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick 1996, Curry and Delaney 2002, Brown 1994). Here we report an observation of regurgitation of a pellet by a Western Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma californica) and describe the specimen and its contents. The Western Scrub-Jay is omnivorous and forages on a variety of arthropods as well as plant seeds and small vertebrates (Curry et al.