The Hudson-Fulton-Champlain Quadricentennial Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Poughkeepsie's Upper

A Short History of Poughkeepsie’s Upper Landing Written by Michael Diaz Chapter 1: Native Americans, the Dutch, and the English When Henry Hudson and his crew first sailed past what is now the City of Poughkeepsie in 1609, they sailed into a region that had been inhabited for centuries by a mixture of Algonquin-speaking peoples from the Mahican, Lenape, and Munsee cultures. The people living closest to the waterfall called “Pooghkepesingh” were Wappinger, part of the Lenape nation. The Wappinger likely had ample reason to settle near the Pooghkepesingh falls – the river and the small stream that ran to it from the falls provided good places to fish, and the surrounding hills offered both protection and ample opportunities to hunt. As the Dutch colony of New Netherland took shape along the banks of the Hudson River, the Dutch largely bypassed the river’s east bank. The Dutch preferred settling on the river’s mouth (now New York City), its northern navigable terminus (today’s Albany), and landings on the western bank of the Hudson (such as the modern city of Kingston). As such, Europeans did not show up in force near the Pooghkepesingh falls until the late 17th century. By that time, the Dutch had lost control of their colony to the English. It was a mix of these two groups that started building what is now the city of Poughkeepsie. On May 5, 1683, a Wappinger named Massany signed a deed giving control of the land around the Pooghkepesingh falls to two Dutch settlers, Pieter Lansingh and Jan Smeedes, who planned to build a mill on the small creek running from the falls. -

Assemblymember Didi Barrett

“We have such beautiful parks and historic sites in this region for families and friends to explore together.” — Assemblymember Didi Barrett Dear Neighbors, I hope you are having a good summer, enjoying time with family and friends. We are so fortunate, here in the Hudson Valley, to have a spectacular array of beautiful parks and historic sites. From the magnificent Hudson River to the verdant Taconic Mountains, the 106th Assembly District has world-class destinations to be enjoyed by tourists and local residents alike. As a member of the Assembly Committee on Tourism and Parks, I am committed to preserving and supporting these nearby treasures where anyone can hike, bike, camp, swim or just stroll. So, go out and visit one of our terrific state and county parks. Sincerely, Didi Barrett, Member of Assembly Didi BarrettAssemblymember Poughkeepsie District Office Hudson District Office 12 Raymond Ave., Suite 105, 751 Warren St. Poughkeepsie, NY 12603 Hudson, NY 12534 845.454.1703 518.828.1961 [email protected] assembly.state.ny.us/mem/Didi-Barrett lymember Didi B Assemb Historic Sites arrett: Explore the beauty in your backyard! State Parks Rail Trails Historic Sites Lake Taghkanic James Baird State Park Harlem Valley Rail Trail Home of Franklin D. Eleanor Roosevelt Staatsburgh State Lake Taghkanic State Park, James Baird State Park, The Harlem Valley Rail Trail runs Roosevelt National National Historic Site Historic Site along Lake Taghkanic in located near Pleasant Valley, is through eastern Dutchess and Historic Site Once home to Eleanor This historic country home Columbia County, offers tent home to the James Baird State Columbia counties and currently Roosevelt, this National Historic of Ogden Mills and his wife and trailer campsites, as Also known as “Springwood,” Park Golf Course, picnic areas, includes 15 miles of paved trails Franklin D. -

Vendor Application

walkway.org/walktoberfest Page 1 of 5 ~ VENDOR APPLICATION The Walkway Over the Hudson and the Hudson Valley Rail Trail The Ultimate Hudson Valley Product Showcase TWO DAYS - Saturday and Sunday, October 3 & 4, 2020, 12 - 5 p.m. Location is the west entrance to the Walkway Over The Hudson WALKTOBERFEST – Vendor Application VENDOR SPACES ARE LIMITED. Vendors will be chosen by the Walkway Selection Committee (Vendor fees are not refundable) THIS AGREEMENT made this _______ day of _____________ 2020, between WALKWAY herein referred to as “FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT” and _____________________________ herein referred to as “VENDOR” for exhibition space in the Festival Marketplace area for the festival held at the Walkway Over The Hudson™ to be held on Saturday and Sunday October 3 – 4, 2020. Business Name: __________________________________________________________________________ Contact:__________________________________________________________________________________ Address:_________________________________________________________________________________ City__________________________________________________State___________Zip_________________ Telephone (daytime): ____________________________Cell:___________________________________ Fax: ______________________________________ E-mail:________________________________________ Website:_________________________________________________________________________________ New York Sales Tax ID#:___________________________________________________________________ # Admission Passes Needed for Staff/Owners______________________________________________ -

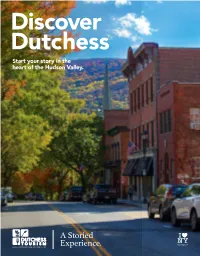

Destination Guide 2020 All Phone Numbers Are in (845) Area Code Unless Otherwise Indicated

ELCOMEELCOME Dutchess County delivers the rugged, natural beauty of the Hudson Valley, world renowned dining, and a storied history of empire builders, visionaries and artists. Take a trip here to forge indelible memories, and discover that true wealth is actually the exceptional experiences one shares in life. Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, Red Hook Table of Contents Events . 2 Eastern Dutchess . .. 30 Groups, Meetings Explore Dutchess by Community . 4 Where to Stay . 38 & Conferences . 46 Northern Dutchess . 6 Places to Eat . 42 Accessible and LGBTQ Travel . 47 Central Dutchess . 14 Colleges . 44 About Dutchess . 48 Southern Dutchess . 22 Weddings . 45 Transportation & Directions . 49 Dutchess Tourism, Inc. is On the cover: Main Street Beacon accredited by the Destination Marketing Accreditation Program (DMAP) of DutchessTourism.com #MyDutchessStory Destinations International. Notes: To the best of our knowledge, the information in this guide is correct as of March 1, 2020. Due to possible changes, we Custom publishing services provided by recommend that you contact a site before visiting. This guide lists only those facilities that wish to be included. Listings do not represent an endorsement. The programs provided by this agency are partially funded by monies received from the County of ChronogramMedia Dutchess. This travel guide is published by Dutchess Tourism, Inc., 3 Neptune Rd., Suite A11A, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601, the County of Dutchess, in cooperation with the New York State Department of Economic Development and the I Love New York 314 Wall Street, Kingston, NY 12401 campaign. ® I LOVE NEW YORK is a registered trademark and service mark of the New York State Department of Economic ChronogramMedia.com Development; used with permission. -

Dutchess Rail Trail I Hudson

d R h t Town of Poughkeepsie r 9G o 9 100 N 9W Street Dutchess 115 n Community lto Fu e College N u e d n w a F e o P a Inwood Avenue v R a R i d l r A d Morgan Lake Trailhead t a v et Ro z ar Stre l Marist i Ced l k e e E d e n w e e Main College P r t C e St et Stre A l Cedar o k W v i e e V e Walkway e e n 2.0 v 1 r k LEGEND: A u Underhill Road 55 i C d e p r Over the a n 44 y r e u e n i Hudson T Dutchess Rail Trail u V l n l Highland Buckingham Ave * i e Trailhead ie Restored Maybrook s v p K Morgan P e A l o e l t r 4 Miles + from west end of f ughk ie e Rail Line Signal r Veterans Memorial Mile n n - o s Lake a o i u Town p o 1 P P F n Walkway Over the Hudson to o e t 3.0 ughk e lt e g Sa v A City of n H end of Hudson Valley Rail Trail i u Parking h d d d a (at Tony Williams Park) s n o s a r o a e 75 G R n u * 11.0 W n V e r a F v ne l Delafield A g * l a e il Street r Portable Toilet (Closed in Winter) y Tra e W Rail Walkway Over the Hudson k n r a Pa V 9G t h e t e r t u t Elevator e o e r n F e r t Handicap Accessible Portable Toilet ek N e e (City/Town Line) r e C e S 44 e to r l r v t 55 il t h K t t Walkway A s all S i T F S l Mill Street m 38 S u s i c U e City of Poughkeepsie k 10.0 n Mile Marker Location f v e i n n n I r o r o D o Poughkeepsie t D 44 t y 2 l i 9W t s r n i i Train u v n W m l Trailhead Main b ( es e C u Street tb a DeLaval Station o m u Road o n H u d N Marple l C 44 N Place o Mid-Hudson Bridge D Town of Poughkeepsie e C g Bridge (Rail Trail goes under/over road) Road a r , m 55 r o d e R y t Main A -

Attraction Highlights

3 Neptune Rd. Suite A11A PoughKeepsie, NY 12601 DutchessTourism.com Daytrip excursions from NYC — Hudson River Valley MAP Nancy Lutz It’s so easy to reach Dutchess County from New York City by car or train. The train Director of Communications line runs along the Hudson River for a beautiful scenic ride from NYC in about an Staatsburgh State Historic Site hour & 40 minutes. Take Amtrak from Penn-Station or Metro-North Railroad from Photo: Andrew Halpern 845-463-5446 / [email protected] Grand Central Station. Amtrak Hudson River views, Great Estates, farms & markets, cultural attractions, culinary adventures, Amtrak stops in Poughkeepsie and Rhinecliff natural scenic beauty, only 90 minutes from NYC – in the heart of the Hudson Valley! Stations. Groups can request a Rails & Trails guide for a narrated journey. Attraction Highlights Amtrak.com Crown Maple at Madava Farms Metro-North Railroad Tour the world’s largest maple sugarhouse, sample handmade sugar and Service from Grand Central maple syrup including Bourbon Barrel Aged syrup, shop, dine on farm fresh Station to Beacon and food and explore the 800 acres of densely forested maple trees. Poughkeepsie. MTA.info Crown Maple at Madava Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Home, Library & Museum Enjoy a guided tour of the birthplace of America’s 32nd U.S. President and the home where he hosted dignitaries such as Winston Churchill and Great Britain’s King George VI. Then visit America’s first presidential library, originally designed by FDR himself, and the only used by a sitting president. Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site Tour the country estate and Gilded Age mansion of Frederick Vanderbilt, th Home of FDR Home of FDR one of the richest men in America of the 19 century. -

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT Moving Dutchess 2 South

FINAL DRAFT Moving Dutchess 2 Chapter 5 Since the county’s transportation system is an inter-related, multi-jurisdictional network, it is useful to first discuss it in Transportation & Resource Overview terms of corridors. Corridors, which cut across transportation modes and municipal boundaries, are the key paths for inter- Moving Dutchess 2 seeks to identify projects and plans and intra-county travel. The previous Moving Dutchess necessary to maintain the transportation system in a state of identified three key transportation corridors in Dutchess good repair and meet future travel needs, while preserving County: the Hudson, Mid-County, and Harlem Valley corridors our natural and historical resources in the most sustainable (see Figure 5-1). manner possible. Inventorying and assessing existing conditions is a necessary step in this process. This chapter Hudson Corridor provides an overview of transportation facilities and resources Located in the western portion of the county and centered on in Dutchess County. The first section discusses the key the Hudson River, the Hudson Corridor has been the components of the transportation system including roads, traditional focus of activity in the county. Its proximity to the bridges, transit, sidewalks, trails, and bicycle facilities, as well Hudson, led to the development of densely populated centers as descriptions of park-and-ride facilities, freight movement, in Beacon and Poughkeepsie. The corridor contains the most transportation safety and security, and ADA accessibility. The robust transportation system in the county, including three second section discusses key natural and historical resources major north-south highways (Routes 9, 9D, and 9G), passenger in the county, including wetlands, floodplains, air quality, agricultural land, and historic districts. -

Walkway Over the Hudson Quality of Life Impact Study

Walkway Over the Hudson Quality of Life Impact Study Quality of Life Impact Study Hudson Valley Pattern for Progress August 2018 P a g e | 2 Executive Summary Finding its way into corporate logos and panoramas over coffee-shop counters, the Walkway Over the Hudson State Historic Park (WOTH) is one of the architectural and scenic icons of the Hudson Valley region. A miracle of modern engineering when it was first constructed from an abandoned railroad bridge, it is the world's longest elevated pedestrian bridge – spanning 1.28 miles over and 212 feet above the Hudson River. With roughly half a million visitors each year, the Walkway has hosted nearly 5 million visitors since its opening in October 2009. The Walkway attracts local area residents and visitors from all 50 states and at least 42 countries and drives visits to a rich array of nearby amenities ranging from bike paths to historic sites and commercial areas.1 At the request of the Board of Directors of the Walkway Over the Hudson organization (the nonprofit friends group established to support the State Park, fund capital improvements and amenities, and host community events), Hudson Valley Pattern for Progress conducted an analysis of how the WOTH has impacted the quality of life (QoL) of the residents in the surrounding Poughkeepsie-Highland community. Several prior studies have focused on the Walkway’s ability to attract visitors to the area as well as the economic impacts of this popular tourist destination. This study reviews the impact that the Walkway has had on the everyday lives of the people living in and around the City of Poughkeepsie and the Hamlet of Highland, and whether its existence has made a measurable improvement in the QoL of local residents. -

Hudson River Valley Institute Walkway Over the Hudson Oral Histories Shirley Mcclintock

Hudson River Valley Institute Walkway Over the Hudson Oral Histories Shirley McClintock Interviewer: So I am reading through here, your mother Mary was the niece through John O’Rourke the chief engineer for the railroad bridge is that correct? Shirley McClintock: Yes that is correct. Interviewer: He chief construction of the bridge. McClintock: No during construction, his obituary, I think obituary from the New York Times Monday, July 30th 1934 and amongst the items that they comment upon. Let me see if I can see the part about the bridge there’s a heading here, “Built Poughkeepsie Bridge,” “while still a young man Mr. O’Rourke was indentified as … and was engineer [Sound goes completely out] McClintock: To finance the recovery of the O’Rourke’s who were trying to put the bridge up so that financial rescue enabled him to start all over again. 101:20 [Sound fades to whisper] So the second attempt succeeded and I’ve learned since attending the public hearing a few weeks ago that the caissons were a crucial part of the success of the bridge and I don’t know whether it was his innovation or whether it had been tried before but evidently the caissons are anchored on large stones and they are still in place and are worthy of maintaining the bridge. 101:51 [Sound completely out] 101:55 [Sound as a whisper] John O’Rourke was an engineer and an inventor, of his successes were based on his attempting things for the first time and one of the things. Camera Man: Stop things for a second, were having technical difficulty Camera Man: Will start from the top with everything McClintock: Okay. -

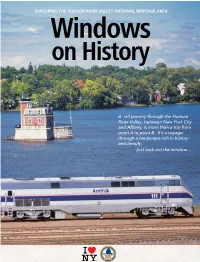

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY. -

Complete Information

Valley Greenway, partners, and sponsors. and partners, Greenway, Valley Ulster Counties. Counties. Ulster Additional support provided by Ulster County IDA, Hudson Hudson IDA, County Ulster by provided support Additional out Dutchess and and Dutchess out and snowshoeing. and Cuomo’s Regional Economic Development Council Initiative. Initiative. Council Development Economic Regional Cuomo’s - through interest Seasonal activities include mountain biking biking mountain include activities Seasonal and its I LOVE NEW YORK program under Governor Andrew Andrew Governor under program YORK NEW LOVE I its and at key points of of points key at Park, with more strenuous trails toward the peak. peak. the toward trails strenuous more with Park, made possible by grants from Empire State Development Development State Empire from grants by possible made of discovery signs signs discovery of The Greater Walkway Experience and digital presence is is presence digital and Experience Walkway Greater The swimming, and gentle hiking paths at Berean Berean at paths hiking gentle and swimming, ence 360-degrees 360-degrees ence Enjoy recreational fishing, picnicking, lake lake picnicking, fishing, recreational Enjoy - Experi Walkway Look for Greater Greater for Look the I Love NY app. app. NY Love I the A recreation zone for all levels of adventure adventure of levels all for zone recreation A Over the Hudson on on Hudson the Over Look for Walkway Walkway for Look Illinois Mountain/Berean Park Mountain/Berean Illinois Experience! Experience! Franny Reese. Reese. Franny Check out our website for more about the Greater Walkway Walkway Greater the about more for website our out Check for Scenic Hudson founding member and activist activist and member founding Hudson Scenic for scenic overlooks and 2.5 miles of trails, named named trails, of miles 2.5 and overlooks scenic walkway.org Enjoy this stunning 250-acre state park with with park state 250-acre stunning this Enjoy A wild woodland preserved preserved woodland wild A residential uses. -

Poughkeepsie Waterfront

Poughkeepsie Waterfront LED lights illuminate the Walkway over the Hudson Poughkeepsie Mid-way between Manhattan and Albany Mid-way between Nieuw Amsterdam and Beverwijck DthDutchess County t A region of PtPaten ts becomes a County with Towns The History of Upper Landing Upper Landing Committee A symbol indicates the presence of Lewis Mill on the north shore of the Fallkill Creek Poughkeepsie Once Capital of New York State now the Dutchess County Seat R. L. Livingston’s Store & Mills labeled on a 1799 map showing “Upper Landing” In 1814 the homes of Mrs. Reynolds and Mrs. Sherman are first shown 1874 Upper Landing is a Commercial Hub 1887 Sanborn Map – Hub of Industry Poughkeepsie Store Fallkill Dye Knitting Works Mill Cedar Lumber Yard Hill Mill Chair Making Dam, Flume & Saw Mill Freight Trains and Passenger Boats 1913 Central Hudson acquires Upper Landing Night Watchman, Hahn Portable Clock 4 Stations, Hourly Rounds Power & Heat: Steam Fuel: Coal Lights: Gas & Electric Building containing 2 Steam TbiTurbines Hoffman House Reynolds House Historical Significance Hoffman House and Reynolds House Mill on the Fallkill at Upper Landing The Port of Poughkeepsie was first used for shipping goods and later for transporting people. 19th Century Reynolds House was once a residential general store. Listed as Local Landmark Foundation of Hoffman House dates to early Dutch and Walloon period Upper Landing 100 years ago in the first quarter of the 1700’s. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places Listed as a Local Landmark. 2006 City of Poughkeepsie Acquires Upper Landing Reasons for Acquisition 1. Public Access – Trail connection between Waryas and Dutton Property 2.