2013 - Narf Case Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Magazine

UCLA Volume 27 Q Fall 2004 LAW LAW Volume 27 27 Volume Q Fall 2004 Dean Michael H. Schill Building on a Tradition of Innovation UCLA LAW The Magazine of the School of Law contents 2 Dean’s Message 4 Dean’s Events 6 Go West, Young Man 10 History of UCLA School of Law: A Tradition of Innovation 18 UCLA Clinical Education: Bridging the Gap Between the Classroom and the Courtroom 24 UCLA School of Law Think Tanks: Providing Relevant Scholarship and Reliable Data for Real Issues 30 UCLA School of Law Emphasizes an Interdisciplinary Approach 34 UCLA Students Capitalize on Third Year Opportunities 40 After the JD: A Pathbreaking Study of the Lives of Young Lawyers 46 2004 Commencement 48 Faculty 49 Focus on Faculty 53 New Faculty 58 Recent Faculty Books 64 Faculty Honors 66 Tribute to Norm Abrams, Interim Dean 68 In Memoriam 70 Events 74 Students Moot Court Student Awards In Memoriam Law Fellows Public Interest 82 Development Major Gifts Law Annual Fund 87 Alumni Innovative Alumni Alumni Events Mentor Program Class Notes Planned Giving message from the dean s I assume the deanship of impact of living wage laws on employment and bankruptcy laws UCLA School of Law, I am on corporations. A tremendously excited Throughout this magazine, you will read of the myriad ways in about the prospects for this great insti- which UCLA has approached the study of law and the development of tution. Founded only fifty-five years its programs—both curricular and extra-curricular—with a truly ago, UCLA School of Law is the original mindset. -

Kickapoo Tribe by Jacob

Kickapoo Tribe by Jacob Questions and answers: Where did the tribe live? Where do the people live now? The Kickapoo Indian people are from Michigan and in the area of Great Lakes Regions. Most Kickapoo people still live in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. What did they eat? The Kickapoo men hunted large animals like deer. They also eat com, cornbread call "'pugna" and planted squash and beans. What did they wear? The women wore wrap around skirts. Men wore breechcloths with leggings. What special ceremonies did they have? The Kickapoo people were very spiritual and connected with animals and they had special ceremonies when it came to hunting. A display of lighting and thunder, usually in early February signifies the beginning of the New Year and hence the cycle of the ceremonies. Some of the ceremonies would be hand drum, dancing and singing. What kind of homes did they build? The Kickapoo people made homes called wickiups and Indian brush shelters. 5 Interesting Facts of the Kickapoo People: 1. Story telling is very important to the Kickapoo Indian culture. 2. Kickapoo hunters & warriors used spears, clubs, bows and arrows to hunt for food. 3. Ho (pronounced like the English word Hoe) is a friendly greeting. 4. Kepilhcihi (pronounced Kehpeeehihhih) means "thank you." 5. The Kickapoo children are just like us. They go to school, like to play and help around the house.. -

John Herrington Born in Chickasaw Nation, John Bennett Herrington Is a Retired United States Naval Aviator and Former NASA Astronaut

John Herrington Born in Chickasaw Nation, John Bennett Herrington is a retired United States Naval Aviator and former NASA astronaut. In 2002, Herrington became the first enrolled member of the Native American tribe to fly in space. This was abord the Space Shuttle Endeavor’s STS-113 mission. Tom Bee and Douglas Spotted Eagle Following a three-year lobbying effort by Ellen Bello, founder of the Native American Music Awards and the Native American Music Association, the Grammy award was first presented to Tom Bee and Douglass Spotted Eagle in 2001 as the producers of the compilation album Gathering of Nations Pow Wow. In 2011, the category Best Native American Music Album was eliminated along with thirty others and replaced. Native American works will now be eligible for the Best Regional Roots Music Album category. Susan La Flesche Picotte Born on the Omaha reservation in northeastern Nebraska on June 17th, 1865, Susan La Flesche Picotte was a Native American doctor and reformer in the late 19th century. She is widely acknowledged as the first Native American to earn a medical degree. She campaigned for public health and for the formal, legal allotment of land to members of the Omaha tribe. Before becoming a place to honor and celebrate the life and word of Picotte, the Susan La Flesche Picotte Center was once a hospital named after her, then a center that cared for the elderly. She lived till 1915. Stanley Crooks From 1992 to 2012, Stanley Crooks served as the first chairman of Shakopee Mdewakanton, America’s richest Native American tribe near Minneapolis, MN. -

BOOK Revtews Send to [email protected] Digital Book Design and Publishing by Dr

BOOK REVtEWS Send to [email protected] Digital Book Design and Publishing by Dr. Douglas REFERENCE Holleley (Clarellen and earJ. Graphic Arts Press, 2001, $be T?be Art of Book: From Medievsll Mannscfipt to $39.95) is an essential reference tool for photograpllers, Graphic Novel, edited by James Behtlq (London, Victoria artists, designers and writers who want to move beyond the SZ Albert Museum Publications, 2001 dist. by Hanq' N. manuscript to the page. Based on his years of work as a Abrams, $49.50) celebrates tlre photograplier, boo rs and teaclrer, Holleley lus on the written md printed page, developed a clear and considered approach to digital book many of are treasures &om the National Art Library at the 6t design. V A Museum. In clear limpid prose, Holleley slrows the process of A tribute to tl~evast collections of &e venerable V 62 A ng from a consideration of maquette and Museum in London, &is volume features six centuries of materials, tluough printing and bookbinding, as well as a illuminated manuscripts, fine bindings, classics of children's step-by-step guide to page layout and image processing literature, comic novels, artist books, advertising, software. A how-to with a difference, this book has a rich magazines, hip contemporary artists, exploring the way and varied selection of full-color reproductions from books not only transmit information but become works of art lristorical and contemporary illustrated books and artist in their own right. books wldclr place digital books in a historical continuum. llre range is from Leonardo da Vince to Barq Moser, Where else would you find examples of bookworks from Aesop to ClwIes Dickens, Babx are Efeplmt to Maus by Spiegelman, and so much in-between. -

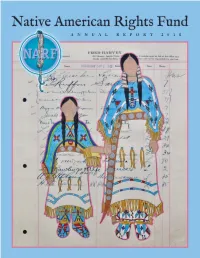

NARF Annual Report 2018(A)

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Director’s Report .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chairman’s Message ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Board of Directors and National Support Committee ........................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Preserving Tribal Existence .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Protecting Tribal Natural Resources .................................................................................................................................... 9 Promoting Human Rights .................................................................................................................................................... 17 Holding Governments Accountable .................................................................................................................................... 24 Developing Indian Law ....................................................................................................................................................... -

George Herms

GEORGE HERMS Born in Woodland, California 1935. Educated University of California, Berkeley 1955. Currently resides in Los Angeles. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2008 Lymphatic Vessels and Monoprints celebrating the life and art of Bruce Conner , Susan Inglett Gallery, New York. 2007 George Herms: Assemblages , Galerie Vallois, Paris. 2006 Select Works , Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York. 2005 George Herms: Hot Set (Walter Hopps, curator), Santa Monica Museum of Art. Pandora’s Box: The Sculpture of George Herms, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento. From George Herms with LOVE, Tobey C. Moss Gallery, Los Angeles. 2004 Sepia Jones Collages , Ace Gallery, Los Angeles 2003 Sepia Jones Collages , Ace Gallery, Los Angeles 2002 Then and Now , Seraphin Gallery, Philadelphia (catalogue) 2002 Teragrams and Roses, Mesa Nights: A Romance of the Old Southwest , Redbud Gallery, Houston, Texas 2001 Bed of Roses..., Assemblages , Catherine Clark Gallery, San Francisco 1999 Poet Heroes of My Youth, Assemblage/Sculpture , Fred Spratt Gallery in association with Larry Evans/James Willis Gallery, San Francisco, California (catalogue) 1998 Parade of Sculpture, First Street Bridge Project, Los Angeles, with laser installation by Hiro Yamagata Office of the Future, Robert Berman Gallery, Bergamot Station, Santa Monica, California 1996 George Herms: Works Saluting San Francisco, 1962-1996,” Catherine Clark Gallery, San Francisco The Beat Bar” Track 16 Gallery and Robert Berman Gallery, Bergamot Station, Santa Monica, California Crossings, Fred Spratt Gallery, San Jose, -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover cover next page > title: American Indian Holocaust and Survival : A Population History Since 1492 Civilization of the American Indian Series ; V. 186 author: Thornton, Russell. publisher: University of Oklahoma Press isbn10 | asin: 080612220X print isbn13: 9780806122205 ebook isbn13: 9780806170213 language: English subject Indians of North America--Population, America-- Population. publication date: 1987 lcc: E59.P75T48 1987eb ddc: 304.6/08997073 subject: Indians of North America--Population, America-- Population. cover next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/cover.html[1/17/2011 5:09:37 PM] page_i < previous page page_i next page > Page i The Civilization of the American Indian Series < previous page page_i next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/page_i.html[1/17/2011 5:09:38 PM] page_v < previous page page_v next page > Page v American Indian Holocaust and Survival A Population History Since 1492 by Russell Thornton University of Oklahoma Press : Norman and London < previous page page_v next page > file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX00.794/080612220X/files/page_v.html[1/17/2011 5:09:38 PM] page_vi < previous page page_vi next page > Page vi BY RUSSELL THORNTON Sociology of American Indians: A Critical Bibliography (With Mary K. Grasmick) (Bloomington, Ind., 1980) The Urbanization of American Indians: A Critical Bibliography (with Gary D. Sandefur and Harold G. Grasmick) (Bloomington, Ind., 1982) We Shall Live Again: The 1870 and 1890 Ghost Dance Movements as Demographic Repitalization (New York, 1986) American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman, 1987) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thornton, Russell, 1942 American Indian holocaust and survival. -

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments by Thomas J. Sloan, Ph.D. Kansas State Representative Contents Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments ....................................... 1 The Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas ..................... ................................................................................................................... 11 Prairie Band of Potawatomi ........................... .................................................................................................................. 15 Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska .............................................................................................................................. 17 Appendix: Constitution and By-Laws of the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas ..................................... .................. ............................................................................................... 19 iii Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments Overview of American Indian Law cal "trust" relationships. At the time of this writing, and Tribal/Federal Relations tribes from across the United States are engaged in a lawsuit against the Department of the Interior for At its simplest, a tribe is a collective of American In- mismanaging funds held in trust for the tribes. A fed- dians (most historic U.S. documents refer to "Indi- eral court is deciding whether to hold current and -

Arizona's Inspirational Women

Arizona’s Inspirational Women Patch Program Guide ARIZONA’S INSPIRATIONAL WOMEN Patch Program Guide GREETINGS! The Arizona’s Inspirational Women Program is a collection of stories about women who have demonstrated a life-time of confidence, courage, and character and have made Arizona and our world a better place. By sharing these generational stories, we believe that current Girl Scouts will find hope and inspiration and learn about how they can also make our communities a better place. WHAT “INSPIRATIONAL” MEANS TO US » Lives by the Girl Scout Promise and Law » Is dedicated to a passion or a cause of choice » Stands up for what she believes in » Shows kindness and compassion towards other women and girls The activities included for the Arizona’s Inspirational Women Patch Program are structured around three components and are available for girls in all levels of Girl Scouts. You will work with your Troop Leaders to take-action through a hands-on activity that represents the inspirational woman’s life you are exploring. This program features numerous women that you can learn about--you may choose just one or as many as you’d like! By completing the activities for one or more of the women, you will earn the main patch, and the rocker with that woman’s name. Each year, a committee of volunteers will add worthy women to this patch program, so the list of women you can learn about will grow. Annually, GSACPC will host an event where we will announce the new women who have been added to the program that year. -

Great Falls Genealogy Library Current Collection October, 2019 Page 1 GFGS # Title Subtitle Author Co-Author Copyright Date

Great Falls Genealogy Library Current Collection October, 2019 GFGS # Title Subtitle Author Co-Author Copyright Date 1st Description 4859 Ancestral Lineages Seattle Perkins, Estelle Ruth 1956 WA 10748 ??Why?? Pray, Montana Doris Whithorn 1997 MT Historical & Genealogical Soc. of 3681 'Mongst the Hills of Somerset c.1980 PA Somerset Co.,Inc 5892 "Big Dreams in a Small Town" Big Sandy Homecoming 1995 1995 Homecoming Committee 1995 MT 7621 "Come, Blackrobe" De Smet and the Indian Tragedy Killoren, John J., S.J. 2003 Indians 10896 "Enlightened Selfishness": Montana's Sun River Proj Judith Kay Fabry 1993 MT 10312 "I Will Be Meat Fo My Salish"… Bon I. Whealdon Edited by Robert Bigart 2001 INDIANS 7320 "Keystone Kuzzins" Index Volume 1 - 8 Erie Society PA 10491 "Moments to Remember" 1950-1959 Decade Reunion University of Montana The Alumni Center 1960 MT 8817 "Our Crowd" The Great Jewish Families of New York Stephen Birmingham 1967 NEW YORK 8437 "Paper Talk" Charlie Russell's American West Dippie, Brian W. Editor 1979 MT 9837 "Railroads To Rockets" 1887-1962 Diamond Jubilee Phillips County, Montana Historical Book Committee 1962 MT 296 "Second Census" of Kentucky - 1800 Clift, G. Glenn c.1954 KY "The Coming Man From Canton": Chinese Exper. In 10869 Christopher W. Merritt 2010 MT MT 1862-1943 9258 "The Golden Triangle" Homesteaading In Montana Ephretta J. Risley 1975 MT 8723 "The Whole Country was…'One Robe'" The Little Shell Tribe's America Nicholas C. P. Vrooman 2012 Indians 7461 "To Protect and Serve" Memories of a Police Officer Klemencic, Richard "Klem" 2001 MT 10471 "Yellowstone Kelly" The Memoirs of Luther S. -

Cultural Implications of Being a Cross-Border Nation

The Kickapoo of Coahuila/Texas Cultural Implications Of Being a Cross-border Nation Elisabeth A. Mager Hois* Elisabeth Mager George White Water, war chief, in front of his summer house in El Nacimiento, Coahuila. rossborder indigenous nations like the O’odham Never theless, the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas (K ttt ) (Pápagos), Cucapá, and the Kickapoo of Coahuila/ reservation is a more powerful magnet, because they set up CTexas, living on both sides of the MexicoU.S. border a casino on that fe deral land and the U.S. federal govern and continually crossing it, are subject to severe cultural in ment awards them certain benefits as an officially recognized fluences by the U.S. Their economic future is north of the tribe. Therefore, the cultural influence on them from the border, and, in power terms, the intercultural relationship be U.S. nation is determinant. In contrast, the Kickapoo com tween Mexico and the U.S. is asymmetrical, since the United munity on the Mexican side serves mainly as a ceremonial States is a world power. In addition, certain privileges enjoyed center, although in recent years, the K ttt has invested a great by U.S.origin tribes facilitate crossborder migration and deal in the countryside in this area with the profits from the their intercultural contact with the two nationstates. Kickapoo Lucky Eagle Casino. Originally from the Great Lakes, the Kickapoo of Coa Thus, crossborder migration from Mexico to the United huil a/Texas have settlements on both sides of the border. States can be explained by the attraction of the latter’s eco n omy, which simultaneously benefits the community in Coa * Professor and researcher at the UNAM School of Higher Learning huila, particularly when the exchange rate for the U.S. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Nominations Submitted to The

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Nominations Submitted to the Senate November 21, 2014 The following list does not include promotions of members of the Uniformed Services, nominations to the Service Academies, or nominations of Foreign Service Officers. Submitted January 6 Jill A. Pryor, of Georgia, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice Stanley F. Birch, Jr., retired. Carolyn B. McHugh, of Utah, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 10th Circuit, vice Michael R. Murphy, retired. Michelle T. Friedland, of California, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit, vice Raymond C. Fisher, retired. Nancy L. Moritz, of Kansas, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 10th Circuit, vice Deanell Reece Tacha, retired. John B. Owens, of California, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit, vice Stephen S. Trott, retired. David Jeremiah Barron, of Massachusetts, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the First Circuit, vice Michael Boudin, retired. Robin S. Rosenbaum, of Florida, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice Rosemary Barkett, resigned. Julie E. Carnes, of Georgia, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice James Larry Edmondson, retired. Gregg Jeffrey Costa, of Texas, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Fifth Circuit, vice Fortunato P. Benavides, retired. Rosemary Márquez, of Arizona, to be U.S. District Judge for the District of Arizona, vice Frank R. Zapata, retired. Pamela L. Reeves, of Tennessee, to be U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District of Tennessee, vice Thomas W. Phillips, retiring.