The Two-Tiered System: Discrimination, Modern Slavery And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Investigation Report Into China's Marine Trash Fish Fisheries

An investigation report into China’s marine trash fish fisheries Media Briefing Greenpeace East Asia The past 30 years have witnessed the aggravation of overfishing as the biggest obstacle for the sustainable development of China's domestic marine fisheries. The official data for China’s marine total allowance catch is 8 to 9 million tons every year1. However, according to China Fisheries Statistic Year Book, China’s marine catch exceed this limit and kept growing since 1994. In 2015, China's marine catch reached 13.14 million tons. Greenpeace East Asia observations show that, although the volume of catch and value of China’s fishing industry has maintained stability overall, its structure has undergone massive changes over the last 50 years. A large part of the total marine catch is now 2 comprised of so called “trash fish” , a mixture of juvenile and undersized fish. Mass fishing of trash fish is causing further damage to China’s coastal marine ecosystem and hindering the much-needed structural adjustment of domestic fisheries. Now we have encountered new opportunities under China’s 13th five year plan, with new policy frameworks in place and ambitious management goals put forward. Tackling trash fish is key to promoting China’s sustainable fisheries development, protecting the marine ecosystem and promoting a sustainable marine economy. In order to better understand China’s trash fish fisheries, Greenpeace East Asia conducted on-site sampling surveys at 22 fishing ports located across the 8 main fishing 3 provinces in the country, including questionnaires for local fishermen, random sampling of trash fish, and collection and analysis of previously documented data and statistics. -

Fukushima Daiichi 2011-2021 the Decontamination Myth and a Decade of Human Rights Violations

Fukushima Daiichi 2011-2021 The decontamination myth and a decade of human rights violations March 2021 01 Contents Executive summary 1 The reality of contamination in Fukushima 2 The decontamination myth 3 Greenpeace surveys 4 Areas where evacuation orders have been lifted – Iitate and Namie 5 Iitate district 6 Namie town and district 7 Namie ‘difficult-to-return’ exclusion zone 8 Strontium-90 – an additional threat 9 Ten years of evacuation, displacement and human rights violations 10 The future of difficult-to-return exclusion zones 11 Conclusion and recommendations Endnotes Cover: Nuclear waste storage area in Iitate, Fukushima prefecture. (October 1, 2017) Page 2-3: Greenpeace survey team in Namie, Fukushima prefecture. (March 26, 2011) © Christian Åslund / Greenpeace 02 Acknowledgements Radiation survey team 2020 Report team 2021 Coordinator and Lead Radiation Protection: Survey data compilation: Jan Vande Putte, Greenpeace Belgium Mai Suzuki, Greenpeace Japan and Mai Suzuki, Greenpeace Japan Researcher: Daisuke Miyachi, Greenpeace Japan Report and analysis : Shaun Burnie, Greenpeace East Asia; Technical support: Jan Vande Putte, Greenpeace Jan vande Putte, Greenpeace Belgium; and Heinz Smital, Belgium and Heinz Smital, Greenpeace Germany Greenpeace Germany Communication/photography support: Review and Editing: Dr Rianne Teule (Greenpeace RPA Mitsuhisa Kawase, Greenpeace Japan coordinator); Kazue Suzuki, Greenpeace Japan; Insung Lee, Greenpeace East Asia; Caroline Roberts Survey teams 2011-2020 Photographs: Christian Aslund; Shaun -

Annual Report 2013

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL CONTENTS 01 Message from the Executive Director 03 02 Message from our Board Chair 04 Our Board Of Directors 05 03 The Global Programme 06 A new way of working 08 The Greenpeace fleet 10 Renewing energy 12 Saving the Arctic 14 Saving the Arctic: The Arctic 30 16 Protecting our forests 20 Defending our oceans 22 Detoxing our world 24 Celebrating ecological food and farming 26 04 People power 28 Our dedicated volunteers 30 Your support: Thank you! 32 05 Organisation Director’s report 36 Greenpeace worldwide abbreviated financial statements 38 Greenpeace International abbreviated financial statements 42 Environmental report 46 Staff members on permanent contract 48 06 Office contact details 50 Written and edited by: Matt Farquharson, Edwin Nichols. We would also like to thank everybody who contributed to this Annual Report. Art Direction and Design by: Atomo Design www.atomodesign.nl Cover image: © Daniel Beltrá / Greenpeace JN 472 © Rose Sjölander / Greenpeace © Rose Sjölander / Greenpeace 2 Greenpeace International Annual Report 2013 SECTION MESSAGE 01 FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Campaigning for a peaceful, just and green future is no longer the job of a specialised few, but the common struggle of all. As the distance between rich and poor grows, and the grip of old power systems wreaks ever more havoc on the natural world, our struggle will and must intensify. The old, polluting industries will not give up without a fight. They have had several hundred years at the top, they exert a corrupting influence at every level of our governments and institutions. We must break their grip on all forms of power. -

2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor Or Forced Labor

From Unknown to Known: Asking the Right Questions to The Story Behind Our Stuff Trace Abuses in Global Supply Chains DOWNLOAD ILAB’S COMPLY CHAIN AND APPS TODAY! Explore the key elements Discover of social best practice COMPLY CHAIN compliance 8 guidance Reduce child labor and forced systems 3 labor in global supply chains! 7 4 NEW! Explore more than 50 real 6 Assess risks Learn from world examples of best practices! 5 and impacts innovative in supply chains NEW! Discover topics like company responsible recruitment and examples worker voice! NEW! Learn to improve engagement with stakeholders on issues of social compliance! ¡Disponible en español! Disponible en français! Check Browse goods countries' produced with efforts to child labor or eliminate forced labor 1,000+ pages of research in child labor the palm of your hand! NEW! Examine child labor data on 131 countries! Review Find child NEW! Check out the Mexico laws and labor data country profile for the first time! ratifications NEW! Uncover details on 25 additions and 1 removal for the List of Goods! How to Access Our Reports We’ve got you covered! Access our reports in the way that works best for you. On Your Computer All three of the U.S. Department of Labor’s (USDOL) flagship reports on international child labor and forced labor are available on the USDOL website in HTML and PDF formats at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor. These reports include Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, as required by the Trade and Development Act of 2000; List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, as required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005; and List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, as required by Executive Order 13126. -

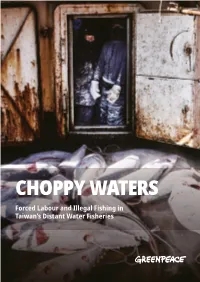

Choppy Waters Report

CHOPPY WATERS Forced Labour and Illegal Fishing in Taiwan’s Distant Water Fisheries TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Introduction 3 Published in March 2020 by: Greenpeace East Asia 3. Methodology 6 No.109, Sec. 1, Chongqing S. Rd, Zhongzheng Dist., Taipei City 10045, Taiwan This report is written by Greenpeace East Asia (hereafter re- 4. Findings 8 ferred to as Greenpeace) to assist public education and scien- Indications of forced labour in Taiwan’s distant water fisheries: Cases and evidence 9 tific research, to encourage press coverage and to promote Reports of the fisher story 9 the awareness of environmental protection. Reading this report is considered as you have carefully read and fully un- Reports of abusive working and living conditions 12 derstand this copyright statement and disclaimer, and agree Possible violations of international standards and Taiwanese labour regulations 13 to be bound by the following terms. Potential cases of IUU fishing 18 Copyright Statement: Potential at-sea transshipments based on AIS records 19 This report is published by Greenpeace. Greenpeace is the exclusive owner of the copyright of this report. 5. How tainted tuna catch could enter the market 22 Disclaimer: FCF’s global reach 22 1. This report is originally written in English and translated How tainted catch might enter the global supply chain via FCF 23 into Chinese subsequently. In case of a discrepancy, the English version prevails. 2. This report is ONLY for the purposes of information sha- ring, environmental protection and public interests. There- 6. Taiwan’s responsibilities 25 fore should not be used as the reference of any investment The international environmental and social responsibility of seafood companies 27 or other decision-making process. -

Report Title

Greenpeace Warns of High Risk for Further Waves of New Coal Plant Approvals in China: data English Summary 29 March 2021 _____________________________________________________________________ On 29 March, 2021, Greenpeace East Asia’s Beijing office released a briefing on research that tracked coal approvals across China. The research briefing includes data on coal approvals across the four fiscal quarters of 2020 and across the five years from 2016 to 2020 (the 13th Five-year plan period). This English summary of that briefing includes: 1. Key findings Pg. 1 2. A new coal boom Pg. 2 3. Figures and tables 1. Figure 1: New approved coal v. overcapacity risk alerts Pg. 3 2. Table 1: 2020 new approved coal by province by quarter Pg. 4 3. Table 2: 13th FYP new approved coal by province by year Pg. 5 4. Overcapacity risks Pg. 6 5. Regional discrepancies in coal approval and energy intensity Pg. 6 6. International impacts of China’s new coal approval spree Pg. 6 7. Recommendations Pg. 7 Key findings 1. 46.1 gigawatts (GW) of coal-fired power plants were approved by local development and reform commissions (DRCs) in China during 2020, 231.6% more capacity than was approved in 2019, and a total 31.9% of the total capacity approved during the 13th Five-year Plan period (2016 - 2020). 2. Twelve provinces continued to approve coal projects in the fourth quarter, notably after the government’s announcement of a carbon emissions reduction target of Net Zero by 2060. These twelve provinces together approved a total 8.1GW(17.5% of the total capacity approved in 2020) during the fourth quarter. -

Annual Report 2020

Greenpeace Japan Annual Report 2020 1 Annual Report 2020 © Taishi Takahashi / Greenpeace Takahashi © Taishi Reflecting on 2020 2020 was the year when COVID-19 transformed that they will stop investing in new coal fired the way we live our lives and altered societal power plants. 2020 was also the year when norms. It was also a year when many of us were Japan, China and South Korea - three of the reminded of the deep connection between world’s most carbon polluting countries - all human health and the natural environment, as we made carbon neutral pledges. Both of these are were warned that the destruction of ecosystems important victories that were possible only with will increase the chances of us being exposed to our donors’ support. similar novel viruses in the future. In Japan and around the world, people’s day to day lives were 2020 was also a significant year for fashion greatly impacted by lockdowns, national states and the environment, with 80 global fashion of emergency and stay-at-home requests. At brands working towards zero toxic chemical Greenpeace Japan we shifted to remote working, emissions by 2020 as part of Greenpeace’s a transition that fortunately did not cause too “Detox Campaign”, which has been running since much disruption, being an organisation that 2011. Following meetings between Greenpeace is used to holding online meetings with staff Japan and Fast Retailing’s (owners of UNIQLO) members all around the world. President Tadashi Yanai and management, the company announced in 2013 that it would 2020 was also a year when climate change- eliminate the usage and emission of all toxic related extreme weather events such as wildfires, chemicals by 2020. -

Greenpeace Dirty Laundry Report

Dirty Laundry Unravelling the corporate connections to toxic water pollution in China image Wastewater being discharged from a pipe from the Youngor textiles factory, in Yinzhou district, Ningbo. Youngor is a major apparel and textiles brand in China. Contents Executive Summary 4 For more information contact: [email protected] Section 1 Introduction: Water crisis, toxic pollution 10 Acknowledgements: and the textile industry We would like to thank the following people who contributed to the creation of this report. If we have forgotten anyone, Section 2 Polluters and their customers – the chain of evidence 32 they know that that our gratitude is also extended to them: Case Study 1: Youngor Textile Complex, Yangtze River Delta 36 Jamie Choi, Madeleine Cobbing, Case Study 2: Well Dyeing Factory, Pearl River Delta 46 Tommy Crawford, Steve Erwood, Marietta Harjono, Martin Hojsík, Zhang Kai, Li Yifang, Tony Sadownichick, Section 3 The need for corporate responsibility 54 Melissa Shinn, Daniel Simons, Ilze Smit, Ma Tianjie, Diana Guio Torres, Vivien Yau, Yue Yihua, Zheng Yu, Lai Yun, Lei Yuting Section 4 Championing a toxic-free future: Prospects 72 Designed by: and recommendations Atomo Design Cover photograph: Appendix 1 81 Pipe on the north side of the 1) Main brands that have a business relationship Youngor factory has finished with Youngor Textile Complex dumping wastewater. The black 2) Main brands that have a business relationship with polluted discharge is clearly visible Well Dyeing Factory Limited © Greenpeace / Qiu Bo 3) The global market shares of sportwear companies JN 372 Appendix 2 92 Profiles of other brands linked with Youngor Textile Complex Published by Appendix 3 96 Greenpeace International Background information on the hazardous Ottho Heldringstraat 5 chemicals found in the sampling 1066 AZ Amsterdam The Netherlands References 102 greenpeace.org Note to the reader Throughout this report we refer to the terms ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’ to describe two distinct groups of countries. -

Greenpeace International Financial Statements 2014

GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL AND RELATED ENTITIES COMBINED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Year ended 31 December 2014 Contents Page: 2. Board report Combined Financial Statements 5. Combined Statement of Financial Position 6. Combined Statement of Comprehensive Income for the year 7. Combined Statement of Changes of Equity for the year 8. Combined Statement of Cash Flows for the year 9. Notes to the Combined Financial Statements Stichting Greenpeace Council Financial Statements 32. Stichting Greenpeace Council Statement of Financial Position 33. Stichting Greenpeace Council Statement of Comprehensive Income for the year 34. Stichting Greenpeace Council Statement of Changes of Equity for the year 35. Stichting Greenpeace Council Notes to the Financial Statements Other information 45. Appropriation of result 46. Independent auditors’ report 1 GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL & RELATED ENTITIES Board report 2014 Board Report The Board of Stichting Greenpeace Council and related entities hereby presents its financial statements for the year ended on 31 December 2014. General Information These financial statements refer to Greenpeace International (GPI) and related entities only. Greenpeace International is an independent, campaigning organisation which uses non-violent, creative confrontation to expose global environmental problems, and to promote the solutions which are essential to a green and peaceful future. Greenpeace's goal is to ensure the ability of the earth to nurture life in all its diversity. Greenpeace International monitors the organisational development of 26 independent Greenpeace organisations, oversees the development and maintenance of our the Greenpeace ships, enables global campaigns, and monitors compliance with core policies. The 26 independent Greenpeace National & Regional organisations are based across the globe. The National & Regional Organisations (NROs) are independent organisations who share common values and campaign together to expose and resolve global environmental problems. -

The Myth of China's Endless Coal Demand

THE MYTH OF CHINA’S ENDLESS COAL DEMAND: A Missing Market For US Exports © Todd Warshaw/ Greenpeace THE MYTH OF CHINA’S ENDLESS COAL DEMAND: A Missing Market For US Exports Table of contents 1. A DESPERATE INDUSTRY—NOT SOUND ECONOMICS— IS DRIVING US COAL EXPORT PROPOSALS P. 4 2. CHina produces nearly all OF THE coal it consumes P. 5 3. CHina’S economic groWTH is sloWing P. 6 4. Coal use in CHina is Flattening out P. 7 5. CHinese policy caps on coal production and consumption Will decouple economic groWTH From coal P. 8 SPOTLIGHT: ReneWABle Energy is Surging in CHina P. 9 Greenpeace is an 6. ReneWABle energy is on THE rise independent campaigning P. 10 organization that acts to expose global 7. CHinese society IS resisting coal and Becoming more environmental problems AWare OF its impacts on HealtH and Water P. 11 and achieve solutions that are essential to a green and SPOTLIGHT: PUBlic Outrage over Air Pollution Curtails Coal peaceful future. Use IN Eastern CHina P. 12 8. UnstaBle Asian demand Has sunK US coal export proposals in THE past Written by Lifeng Fang P. 13 Published February 2013 by Greenpeace USA 9. International competitors recogniZE Flagging CHinese 702 H Street NW Suite 300 demand P. 14 Washington, DC 20001 Tel/ 202.462.1177 10. Summary P. 15 For media inquiries, contact [email protected] book design by andrew fournier THE MYTH OF CHINA’S ENDLESS COAL DEMAND: A MISSING MARKET FOR US EXPORTS The US coal industry—reeling from sagging domestic demand, plum- meting profits, and tanking stock prices—is desperate for a new market Dan Nan wind farm in Nan’ao. -

Greenpeace International Annual Report 2016

2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning organisation that acts to change attitudes and behaviour, to protect and conserve the environment and to promote peace. A Message from the Greenpeace International Executive Directors 4 Greenpeace International’s Board of Directors 5 A Message from the Board Chair 6 Our Work 7 Forests 8 Detox 10 Climate & Energy 12 Food For Life 14 Save the Arctic 16 Oceans 18 Our Ships 20 Our People 22 Greenpeace International Abbreviated Financial Statements 26 Greenpeace Worldwide Abbreviated Financial Statements 28 Environmental Report 30 Office Contact Details 31 3 Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning organisation that acts to change attitudes and behaviour, to protect and conserve the environment and to promote peace. Foreword This is the 2016 Annual Report for Stichting Greenpeace Council. Stichting Greenpeace Council commonly works under its operational name: Greenpeace International. Greenpeace is a network consisting of Greenpeace International and 26 independent National and Regional Organisations (NROs) across the globe. See page [31] for office contact details. For convenience and reading ease, in this annual report Greenpeace is also used to identify Greenpeace International (GPI) and/or one or more Greenpeace NROs. Further information about the NROs involved in specific campaign projects is available online and/or via [email protected]. The words ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ in this report may refer to Greenpeace International, and/or NROs, and supporters. ‘You’ may refer to the reader of this report, and to existing and potential Greenpeace supporters across the world. Greenpeace International’s activities in 2016 In accordance with the Operating Model as agreed by the Greenpeace network in 2014, Greenpeace International has in 2016 further delivered on its coordinating and enabling role for the global Greenpeace network. -

Greenpeace International

Greenpeace International Annual Report to the INGO Accountability Charter, 2013 Submitted: 30 September 2014, by Edwin Nichols, Unit Head of the Performance, Accountability & Learning (PAL) Unit. Greenpeace International Accountability Report 2013 1 Table of Contents. Table of Contents. 2 1. Strategy and Analysis. 4 1.1 Statement of most senior decision-maker. 4 2. Organisational Profile. 6 2.1 Name of the organisation. 6 2.2 Primary activities. 6 2.3 Operational structure. 6 2.4 Location of organisation's headquarters. 7 2.5 Number of countries where the organisation operates, and names of countries with either major operations or that are specifically relevant to the sustainability issues covered in the report. 7 2.6 Nature of ownership and legal form. Details and current status of not-for-profit registration. 7 2.7 Target audience: Groups of people you serve including geographic breakdown.7 2.8 Scale of the reporting organisation including global annual budget; annual income and expenditure, number of e.g. members, supporters, volunteers, employees; total capitalisation in terms of assets and liabilities; scope and scale of activities or services provided. 8 2.9 Significant changes during the reporting period regarding size, structure, governance or ownership. 9 2.10 Awards received in the reporting period. 10 3. Report Parameters. 11 3.1 Reporting period (e.g., fiscal/calendar year) for information provided. 11 3.2 Date of most recent previous report (if any). 11 3.4 Contact points for questions regarding the report or its contents. 11 3.5 Process for defining reporting content and using reporting process.