2002-GINA.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission Report

Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission Report 29 January 2019 Commissioner Bret Walker SC 29 January 2019 His Excellency the Honourable Hieu Van Le AC Governor of South Australia Government House GPO Box 2373 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Your Excellency In accordance with the letters patent issued to me on 23 January 2018, I enclose my report. I note that I have been able to take account of materials available as at 11 January 2019. Yours sincerely Bret Walker Commissioner Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission Report Bret Walker SC Commissioner 29 January 2019 © Government of South Australia ISBN 978-0-6484670-1-4 (paperback) 978-0-6484670-2-1 (online resource) Creative Commons Licence With the exception of the South Australian Coat of Arms, any logos and any images, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Suggested attribution: South Australia, Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission, Report (2019). Contents Acknowledgments 1 Terms of Reference 5 Overview 9 Responses to Terms of Reference, Key Findings & Recommendations 45 1. History 77 2. Constitutional Basis of the Water Act 99 3. ESLT Interpretation 127 4. Guide to the Proposed Basin Plan 163 5. ESLT Process 185 6. Climate Change 241 7. The SDL Adjustment Mechanism 285 8. Constraints 347 9. Efficiency Measures & the 450 GL 381 10. Northern Basin Review 427 11. Aboriginal Engagement 465 12. Water Resource Plans 509 13. -

The Scientific Legacy of the 20Th Century

the Pontifical academy of ScienceS Plenary Session on The Scientific Legacy of the 20th Century 28 October-1 November 2010 • Casina Pio IV Prologue p . 3 Programme p. 4 List of Participants p. 8 Memorandum p. 10 em ad ia c S a c i e a n i t c i i a f i r t V n m o P VatICaN CIty 2010 ertainly the Church acknowledges that “with the help of science and technol - ogy…, man has extended his mastery over almost the whole of nature”, and thus C“he now produces by his own enterprise benefits once looked for from heavenly powers” ( Gaudium et Spes , 33). at the same time, Christianity does not posit an in - evitable conflict between supernatural faith and scientific progress. the very starting- point of Biblical revelation is the affirmation that God created human beings, endowed them with reason, and set them over all the creatures of the earth. In this way, man has become the steward of creation and God’s “helper”. If we think, for example, of how modern science, by predicting natural phenomena, has contributed to the protec - tion of the environment, the progress of developing nations, the fight against epidemics, and an increase in life expectancy, it becomes clear that there is no conflict between God’s providence and human enterprise. Indeed, we could say that the work of predict - ing, controlling and governing nature, which science today renders more practicable than in the past, is itself a part of the Creator’s plan. Science, however, while giving generously, gives only what it is meant to give. -

Table of Contents (PDF)

EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY Impact factor: journal 5.992 CHIEF EDITORS Anh Tuan Dinh-Xuan Vito Brusasco CONTENTS Dept of Cardiorespiratory Dept of Internal Medicine, Medicine, Medical School, VOLUME 39 / NUMBER 6 / JUNE 2012 Cochin Hospital, University of Genoa, University Paris Descartes, viale Benedetto XV, 6, 27, rue du faubourg 16132 Genoa, Saint-Jacques, Italy IN MEMORIAM 75014 Paris, Tel: 39 0103537690 France Fax: 39 0103537690 1283 Prof. Andrzej Szczeklik, 1938–2012: aspirin-induced Tel: 33 158412341 E-mail: [email protected] asthma and much more Fax: 33 158412345 Sven-Erik Dahlén, Barbro Dahlén and Klaus F. Rabe; E-mail: [email protected] Ewa Nizankowska-Mogilnicka, Jacek Musial, Marek Sanak and Piotr Gajewski ASSISTANT TO THE CHIEF EDITORS Sy Duong-Quy Tel: 33 158411942 Fax: 33 158412345 EDITORIALS E-mail: [email protected] 1287 Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction for emphysema: PUBLICATIONS OFFICE where next? Managing Editors: Elin Reeves and Neil Bullen Pallav L. Shah and Nicholas S. Hopkinson 442 Glossop Road, Sheffi eld, S10 2PX, UK 1290 Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Eastern Europe: still Tel: +44 114 267 2860 Fax: +44 114 266 5064 on the increase? E-mail: [email protected]/[email protected] Giovanni Battista Migliori, Masoud Dara, Pierpaolo de Colombani, Hans Kluge and Mario C. Raviglione ASSOCIATE EDITORS N. Ambrosino J. Müller-Quernheim 1292 Pre-implantation genetic testing for hereditary pulmonary Pisa, Italy Freiburg, Germany arterial hypertension: promise and caution I. Annesi-Maesano R. Naeije Rizwan Hamid and James Loyd Paris, France Brussels, Belgium J.L. Black M.I. -

Andrzej Szczeklik Krakow, Poland, 29 July 1938 - 3 Feb

Andrzej Szczeklik Krakow, Poland, 29 July 1938 - 3 Feb. 2012 Nomination 16 Oct. 1994 Field Medicine Title Professor Commemoration – I am honored and grateful to speak in memory of our beloved colleague Andrezej Szczeklik. I met him for the first time at our Academy in 1994 and I will always remember his self-presentation, modest and to the point. He gave a moving testimony of his admiration and love for Pope John Paul II. A few years later he gave me as a gift his inspiring book Catharsis: On the Art of Medicine with a foreword by the great Polish humanist and poet Czes#aw Mi#osz. A continuation of this book is called Kore#: On Sickness, the Sick, and the Search for the Soul of Medicine, a suggestive title that reveals the spirit and mission of a man totally dedicated to his patients and to science. Andrezej Szczeklik was born in 1938 in Cracow, where he studied medicine. He did post-doctoral training and research at the Karolinska Institut, Uppsala University and North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He became professor and chairman of the Jagiellonian University School of Medicine, Cracow, and president of the Copernicus Academy of Medicine. He was a member of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Royal College of Physicians, the American College of Physicians and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He became an active participant in all our Plenary Sessions. He received honorary doctorates from the Schools of Medicine of Wroc#aw, Warsaw, Katowice and #o#dz. He was awarded the Gloria Medicinae Medal by the Polish Society of Medicine. -

Rights Guide

COUNTERPOINT | SOFT SKULL FRANKFURT 2012 | RIGHTS GUIDE CONTACT US: Rights: Judy Klein, Kleinworks Agency [email protected] Liz Parker, Publishing Manager [email protected] HOT LIST Counterpoint | Soft Skull MOTHERLAND by Maria Hummel World English | FICTION | January 2014 | Counterpoint | MSS February 2013 Lifted from the stories of the author’s father and his German childhood and letters be- tween her grandparents that were hidden in an attic wall for fifty years,Motherland focuses on a German family during WWII: a reconstructive surgeon loses his wife in childbirth and two months later marries a young woman who must look after the baby and his two griev- ing sons when he is drafted into medical military service. We follow her attempts to keep them safe as their German city is bombed by the Allies, their town is faced with the swell- ing population of desperate refugees, and one son begins to mentally unravel. Each family member’s fateful choices lead them deeper into questions of complicity and innocence, to the novel’s unforgettable conclusion. Maria Hummel is a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and her work has appeared in Ploughshares, The Sun, The Believer and has won a Pushcart Prize. Her first novel,Wilderness Run (SMP, 2002) was an alternate selection of Doubleday Lit Guild. Remaining Rights: Brandt & Hochman PEERLESS FOUR by Victoria Patterson World English | FICTION | November 2013 | Counterpoint | MSS January 2013 This slender yet powerful novel reimagines the true story of four young women who were among the first females to ever compete in the Olympic Games. It was the summer of 1928, and Valerie Patterson sensitively captures the time and place, the drama and the desire, the glory and the catastrophe of how these girls got there and what happened to them in Amsterdam that year. -

Andrzej Szczeklik: Visionary, Pathfinder, Renaissance Man

Andrzej Szczeklik: visionary, pathfinder, Renaissance man Jacek Hawiger Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, United States Upon hearing the stunning news about Andrzej Szczeklik’s untimely death, I was overwhelmed by its suddenness. I learned from Andrzej’s wife, Maria, and daughter, Ania, how he was in the thick of things until his last days, planning the next Symposium, preparing his next book, and arranging the next trip. He was a patient in his beloved “Klinika”, the 2nd Department of Med- icine of the Jagiellonian University Medical Col- lege in Krakow. “Klinika” was his brainchild and work in progress ever since the communist au- thorities assigned Andrzej in 1972 to the Depart- ment of Allergy and Clinical Immunology while some of us, his peers, were getting junior faculty positions in Poland and abroad. Andrzej had cho- sen to stay in his native Poland and by espous- ing the philosophy of “Organic Work” had turned around his “Post”, the old dilapidated Tubercu- losis Hospital, into a modern marvel of Internal Medicine; he became its Chairman in 1989. By overcoming huge barriers, he transformed grim wards into functional patient rooms; a new wing was built with diagnostic and research labora- tories furnished with the state of the art equip- ment; a new lecture hall and conference rooms FIGURE 20 Professor Szczeklik in the Tatra Mountains were added, where Andrzej’s guests from Euro- that offered to him solace and inspiration; picture taken pean and American universities were sharing ad- by the author in 1992 vanced concepts and techno logical breakthroughs. A new cadre of students and fellows was rigorously trained to become highly accomplished physician- exploration of the vast range of genetic diversity -scientists and scientists. -

Curriculum Vitae Andrzej Ryś

Curriculum Vitae Andrzej Ryś PERSONAL INFORMATION Andrzej Ryś Office B-232 08/135 Rue de Breydel 4 (Brussels, Belgium) Telf: (+32) 229 69667 Emai: [email protected] WORK EXPERIENCE 2014 - Present Director of Health Systems, Medical Products and Innovation Directorate DG SANTE, European Commission, Brussels ▪ Management of 5 units in the Directorate ▪ Development of health technology assessment legislation ▪ Implementation of EU legislation in the field of blood, tissues and organs transplantation, pharmaceuticals, tobacco products directive and patients' rights in cross border- health care ▪ International collaboration in the field of health and pharmaceuticals ▪ Working with stakeholders, including industry and professional organizations ▪ Member of IMI GB (from the beginning) and alternate member of EMA MB 2010 - 2014 Director of Health Systems and Products Directorate DG SANCO, European Commission, Brussels ▪ Management of 5 units in the Directorate ▪ Development of; tobacco products directive , clinical trials regulation, veterinary medicines regulation ▪ Implantation of; patients' rights in cross border- health care directive and pharmaceutical regulations (including newly adopted pharmacovigilance and falsified medicines directives) ▪ Implementation of EU legislation in the field of blood, tissues and organs transplantation ▪ Development of new dossier in the field of health systems (suitability, health economics, work forces, investment in health, including structure funds) ▪ International collaboration in the field of health -

WINTER 2015 | WINTER ASSOCIATION BAR NSW the of JOURNAL the ���THE JOURNAL Ofne�S the NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 201

THE JOURNAL OF THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2015 barTHE JOURNAL OFnes THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 201 Parental responsibilities and the bar PLUS ‘Barristers work’ and ADR The NSW Bar and the Red Cross Missing and Wounded Enquiry Bureau William Lee barnewsTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2015 Contents 2 Editor’s note 54 Bench and Bar Dinner 2015 Red Cross Missing and Wounded Enquiry Bureau 3 President’s column 56 Practice Barristers v Solicitors rugby match, Technology, flexibility and the Uniform Rule 11, ‘barristers’ work’ 1956 twenty-first century advocate and barristers conducting ADR processes 83 Bullfry 4 Chambers Expected value and decision making QC, or not QC? The opening of New Chambers under conditions of uncertainty 85 Appointments 5 Bar Practice Course 01/2015 Learning the art of court performance The Hon Justice R McClelland 6 Recent developments Chambers employment with a The Hon Justice D Fagan difference 28 Features 87 Obituaries Parental responsibilities and the bar The Best Practice Guidelines Geoffrey James Graham (1934–2014) 73 Bar history The powers of the ICAC to 89 Book reviews investigate William Lee: first barrister of 96 Poetry Corrupt conduct: The ICAC’s Chinese descent admitted to the Cunneen Inquiry NSW Bar Alternatives to Australia’s war on drugs Bar News Editorial Committee ISSN 0817-0002 © 2015 New South Wales Bar Association Jeremy Stoljar SC (chair) Views expressed by contributors to Bar News are This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, and subsequent amendments, no part may be Greg Burton SC not necessarily those of the New South Wales Bar reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or Richard Beasley SC Association. -

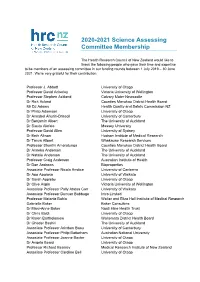

2020-2021 Science Assessing Committee Membership

2020-2021 Science Assessing Committee Membership The Health Research Council of New Zealand would like to thank the following people who gave their time and expertise to be members of an assessing committee in our funding rounds between 1 July 2019 – 30 June 2021. We’re very grateful for their contribution. Professor J. Abbott University of Otago Professor David Ackerley Victoria University of Wellington Professor Stephen Ackland Calvary Mater Newcastle Dr Rick Acland Counties Manukau District Health Board Mr DJ Adams Health Quality and Safety Commission NZ Dr Philip Adamson University of Otago Dr Annabel Ahuriri-Driscoll University of Canterbury Dr Benjamin Albert The University of Auckland Dr Siautu Alefaio Massey University Professor David Allen University of Sydney Dr Beth Allison Hudson Institute of Medical Research Dr Tanya Allport Whakauae Research Services Professor Shanthi Ameratunga Counties Manukau District Health Board Dr Anneka Anderson The University of Auckland Dr Natalie Anderson The University of Auckland Professor Craig Anderson Australian Institute of Health Dr Dan Andrews Bioproperties Associate Professor Nicola Anstice University of Canberra Dr Apo Aporosa University of Waikato Dr Sarah Appleby University of Otago Dr Clive Aspin Victoria University of Wellington Associate Professor Polly Atatoa Carr University of Waikato Associate Professor Duncan Babbage Intro Limited Professor Melanie Bahlo Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research Gabrielle Baker Baker Consulting Dr Mary-Anne Baker Ngati Hine Health Trust -

Professor Andrew Szczeklik: How I Will Remember Him

Professor Andrew Szczeklik: how I will remember him Eugeniusz J. Kucharz Department of Internal Medicine and Rheumatology, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland The name Szczeklik has been well known to Pol‑ I was working in. When I cast back my mind, I am ish medical students for the last half of the cen‑ still experiencing the same thrilling excitement tury at least. It also applies to me. When I was we had in those days. Finally, Poles made an aston‑ a third‑year medical student, one of my course ishing contribution to the world’s medicine after requirements was to thoroughly study the basic so many years of not being significantly visible. handbook on the introduction to clinical medicine, The turn of the 1970s/1980s brought about the book on physical examination, and bed side di‑ meaningful political changes. The Solidarity Union agnostics authored by Professor Edward Szczek‑ was founded in 1980 and, a year later, was crushed lik, the father of Professor Andrew Szczeklik. This down by brutal martial law imposed by the author‑ book, which the students nicknamed “The Small ities of the People’s Republic of Poland. After years, Szczeklik”,1 was the fundamental source of knowl‑ I learnt that Professor Andrew Szczeklik active‑ edge for numerous generations of Polish stu‑ ly participated in the movement of freedom and dents of medicine. The last course of my medical suffered persecution because of his actions. In education required that all students be studying the dark days of the martial law, the 16th Interna‑ “The Big Szczeklik”,2 a two‑volume handbook of tional Congress of Internal Medicine took place in inter nal medicine also edited by Professor Edward the neighboring country, Czechoslovakia (Prague). -

2019 the MRINZ Is New Zealand’S Leading Independent Medical Research Institute and Is a Charitable Trust

2019 The MRINZ is New Zealand’s leading independent medical research institute and is a charitable trust. Our medical scientists are dedicated to investigating the causes of important public health problems, to use this knowledge to improve the prevention and treatment of diseases, and to provide a base for specialist training in medical research. Our particular focus is on research which has the potential to lead to improvements in clinical management. Chairman’s Report It is with great pleasure that I write the preface for the 2019 Annual Report of the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand. A highlight for the year was the benchmarking of the research performance of the MRINZ with the eight universities in New Zealand. This assessment using independent metrics derived from SciVal showed the impact of the research undertaken by the MRINZ markedly outperformed that of the New Zealand universities, and the quality of the publications was also better. These findings reflect the commitment of the MRINZ to undertake quality research that challenges dogma, and has the potential to increase knowledge and change clinical practice. The MRINZ continues to make a major international impact with its clinically-based research aimed at improving the treatment of common medical conditions. The MRINZ has research programmes in the fields of alternative and complementary medicine, asthma, cardiothoracic surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), education, emerging therapeutics, intensive care, Māori and Pacific Health, medicinal cannabis, oxygen therapy, pharmacy, pleural disease, respiratory physiology, rhinothermy, stroke and rehabilitation. Major advances have been made in many of these fields in the last year with the research findings having a significant impact on medical management and public health policy. -

In Memory of Professor Andrzej Szczeklik

In memory of Professor Andrzej Szczeklik J. Christian Virchow Jr, J. Christian Virchow Sr Abteilung für Pneumologie, Intensive Care Medicine, Klinik I, Zentrum für Innere Medizin, Rostock, Germany Andrew Szczeklik visited the Hochgebirgsklinik patients. Andrew later co‑organised a number of Davos for the first time in 1978. At that time, meetings held in Davos together with Christian the clinic was the largest center for chron‑ Virchow Sr. Andrew’s excellent network helped to ic obstructive lung diseases in Western Europe. attract not only the relevant leaders in the field, The cold war was still on. Professor Szczeklik, but also helped to identify future talents. His upon invitation by Christian Virchow Sr man‑ name, however, also attracted a large audience aged to attend the first of a series of focused meet‑ at each one of these meetings. He personally con‑ ings devoted to intrinsic asthma and especially tributed to these conferences with numerous lec‑ aspirin‑induced asthma. He thanked for the in‑ tures. He also brought an aspiring, lovely, young vitation to the first meeting “looking forward to lady from his laboratory with him who impressed a fruitful co‑operation”, which indeed became everybody with her excellent clinical research in true. At that time, leukotrienes had recently been the field of aspirin‑sensitive asthma and with her discovered and Bengt Samuelsson was about to re‑ language skills. Her name was Ewa Niżankowska‑ ceive the Nobel Prize for this in 1982. In addition Mogilnicka who under Andrew’s supervision be‑ to leukotrienes, platelet‑activating factor (PAF) came a world‑known leader in the field, too.