The Quaternary Cuban Platyrrhine Paralouatta Varonai and the Origin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Current Status of the Newworld Monkey Phylogeny Anais Da Academia Brasileira De Ciências, Vol

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências ISSN: 0001-3765 [email protected] Academia Brasileira de Ciências Brasil Schneider, Horacio The current status of the NewWorld Monkey Phylogeny Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, vol. 72, núm. 2, jun;, 2000, pp. 165-172 Academia Brasileira de Ciências Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32772205 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Current Status of the New World Monkey Phylogeny∗ ∗∗ HORACIO SCHNEIDER Campus Universitário de Bragança, Universidade Federal do Pará, Alameda Leandro Ribeiro, s/n – 68600-000 Bragança, Pará, Brazil Manuscript received on January 31, 2000; accepted for publication on February 2, 2000 ABSTRACT Four DNA datasets were combined in tandem (6700 bp) and Maximum parsimony and Neighbor-Joining analyses were performed. The results suggest three groups emerging almost at the same time: Atelidae, Pitheciidae and Cebidae. The total analysis strongly supports the monophyly of the Cebidae family, group- ing Aotus, Cebus and Saimiri with the small callitrichines. In the callitrichines, the data link Cebuela to Callithrix, place Callimico as a sister group of Callithrix/Cebuella, and show Saguinus to be the earliest offshoot of the callitrichines. In the family Pithecidae, Callicebus is the basal genus. Finally, combined molecular data showed congruent branching in the atelid clade, setting up Alouatta as the basal lineage and Brachyteles-Lagothrix as a sister group and the most derived branch. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut Und Museum Alexander Koenig, Bonn

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 2001-2003 Band/Volume: 50 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hutterer Rainer Artikel/Article: Two replacement names and a note on the author of the shrew family Soricidae (Mammalia) 369-370 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at Bonn. zool. Beitr. Bd. 50 H. 4 S. 369-370 Bonn, Januar 2003 Two replacement names and a note on the author of the shrew family Soricidae (Mammalia) Rainer Hutterer In the course of long-term revisionary studies of the fossil and living taxa of the Soricidae G. Fischer, 1817 (Hutterer 1 995 ), and during work for a chapter of the new edition of the world checklist of mammals (Wilson & Reeder in prep.), a number of taxonomic and nomenclatural problems were encountered. These also include two cases of homonymy, which are discussed here and for which replacement names are proposed in accordance with article 60 of the code (ICZN 1999). 1. Replacement name for Stirtonia Gureev, 1979 The genus Limnoecus Stirton, 1930 currently includes two taxa, L. tricuspis Stirton, 1930 and L. niobrarensis Macdonald, 1947 (Harris 1998). James (1963) who compared the type specimens of both taxa concluded that L. niobrarensis was a synonym of L. tricuspis, a view not shared by Repenning (1967). Gureev (1979) concluded that both species were not closely related and he placed L. niobrarensis in a new genus Stirtonia. From the descriptions of both taxa given by Stirton ( 1 930), Macdonald ( 1 947) and James ( 1 963) I am inclined to concur with Gureev (1979). -

Morphometric Variation of Extant Platyrrhine Molars: Taxonomic Implications for Fossil Platyrrhines

A peer-reviewed version of this preprint was published in PeerJ on 11 May 2016. View the peer-reviewed version (peerj.com/articles/1967), which is the preferred citable publication unless you specifically need to cite this preprint. Nova Delgado M, Galbany J, Pérez-Pérez A. 2016. Morphometric variation of extant platyrrhine molars: taxonomic implications for fossil platyrrhines. PeerJ 4:e1967 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1967 Morphometric variation of extant platyrrhine molars: taxonomic implications for fossil platyrrhines Mónica Nova Delgado, Jordi Galbany, Alejandro Pérez-Pérez The phylogenetic position of many fossil platyrrhines with respect to extant ones is not yet clear. Two main hypotheses have been proposed: the layered or successive radiations hypothesis suggests that Patagonian fossils are Middle Miocene stem platyrrhines lacking modern descendants, whereas the long lineage hypothesis argues for an evolutionary continuity of all fossil platyrrhines with the extant ones. Our geometric morphometric analysis of a 15 landmark-based configuration of platyrrhines' first and second lower molars suggest that morphological stasis, may explain the reduced molar shape variation observed. Platyrrhine lower molar shape might be a primitive retention of the ancestral state affected by strong ecological constraints thoughout the radiation the main platyrrhine families. The Patagonian fossil specimens showed two distinct morphological patterns of lower molars, Callicebus -like and Saguinus -like, which might be the precursors of the extant forms, whereas the Middle Miocene specimens, though showing morphological resemblances with the Patagonian fossils, also displayed new, derived molar patternss, Alouatta- like and Pitheciinae -like, thereby suggesting that despite the overall morphological stasis of molars, phenotypic diversification of molar shape was already settled during the Middle Miocene. -

First North American Fossil Monkey and Early Miocene Tropical Biotic Interchange Jonathan I

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature17415 First North American fossil monkey and early Miocene tropical biotic interchange Jonathan I. Bloch1, Emily D. Woodruff1,2, Aaron R. Wood1,3, Aldo F. Rincon1,4, Arianna R. Harrington1,2,5, Gary S. Morgan6, David A. Foster4, Camilo Montes7, Carlos A. Jaramillo8, Nathan A. Jud1, Douglas S. Jones1 & Bruce J. MacFadden1 New World monkeys (platyrrhines) are a diverse part of modern Primates Linnaeus, 1758 tropical ecosystems in North and South America, yet their early Anthropoidea Mivart, 1864 evolutionary history in the tropics is largely unknown. Molecular Platyrrhini Geoffroy, 1812 divergence estimates suggest that primates arrived in tropical Cebidae Bonaparte, 1831 Central America, the southern-most extent of the North American Panamacebus transitus gen. et sp. nov. landmass, with several dispersals from South America starting with the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama 3–4 million years Etymology. Generic name combines ‘Panama’ with ‘Cebus’, root taxon ago (Ma)1. The complete absence of primate fossils from Central for Cebidae. Specific name ‘transit’ (Latin, crossing) refers to its implied America has, however, limited our understanding of their history early Miocene dispersal between South and North America. in the New World. Here we present the first description of a fossil Holotype. UF 280128, left upper first molar (M1; Fig. 2a, b). monkey recovered from the North American landmass, the oldest Referred material. Left upper second molar (M2; UF 281001; Fig. 2a, b), known crown platyrrhine, from a precisely dated 20.9-Ma layer in partial left lower first incisor (I1; UF 280130), right lower second the Las Cascadas Formation in the Panama Canal Basin, Panama. -

New Platyrrhine Tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, Illinois 60115

Daniel L. Gebo New platyrrhine tali from La Venta, Colombia Department of Anthropology, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois 60115. U.S.A. Two new primate tali were discovered from the middle Miocene of South America at La Venta, Colombia. IGM-KU 8802 is similar in morphology to Callicebus and Aotus, and is allocated to cf. Aotus dindensis, while IGM-KU Marian Dagosto 8803, associated with a dentition of a new cebine primate, is similar to Saimiri. Both tali differ from the other known fossil platyrrhine tali, Departments of Cell, Molecular, and Dolichocebus and Cebupithecia, and increase our knowledge of the locomotor Structural Biology and Anthropology, diversity of the La Venta primate fauna. hrorthrerestern lJniuersi;v, Euanston, Illinois 60208, U.S.A. Alfred L. Rosenberger Department of Anthropology, L’niuersity of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60680, U.S.A. Takeshi Setoguchi Primate Research Institute, Kyoto C’niniuersiQ,Inuyama Cily, Aichi 484, Japan Received 18 April 1989 Revision received 4 December 1989and accepted 2 1 December 1989 Keywords: Platyrrhini, La Venta, foot bones, locomotion. Journal of Human Evolution (1990) 19,737-746 Introduction Two new platyrrhine tali were discovered at La Venta, Colombia, by the Japanese/American field team working in conjunction with INGEOMINAS (Instituto National de Investigaciones Geologico-Mineras) during the field season of 1988. These two fossils add to the rare but growing number of postcranial remains of extinct platyrrhines from the Miocene of South America (Stirton, 1951; Gebo & Simons, 1987; Anapol & Fleagle, 1988; Ford, 1990). They represent the first new primate postcranials to be described from La Venta in nearly four decades. -

La Venta Submitted to Primates 11-27-09

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kent Academic Repository 1 Community Ecology of the Middle Miocene Primates of La Venta, 2 Colombia: the Relationship between Ecological Diversity, Divergence 3 Time, and Phylogenetic Richness 4 5 The final publication is available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10764-010-9419-1 6 7 8 Brandon C. Wheeler 9 Interdepartmental Doctoral Program in Anthropological Sciences 10 Stony Brook University 11 Stony Brook, NY 11794-4364 USA 12 Phone: 1-631-675-6412 13 Fax: 1-631-632-9165 14 E-mail: [email protected] 15 16 17 Size of the manuscript: 18 Word count (whole file): 4,622 19 Word count abstract: 229 20 3 tables & 8 figures 21 22 Originally submitted to Primates on July 15, 2009 23 Revision submitted on November 26, 2009 24 1 25 26 2 27 Abstract 28 It has been suggested that the degree of ecological diversity that characterizes a primate 29 community correlates positively with both its phylogenetic richness 30 and the time since the members of that community diverged (Fleagle and Reed 1999). It is 31 therefore questionable whether or not a community with a relatively recent divergence time 32 but high phylogenetic richness would be as ecologically variable as a community with 33 similar phylogenetic richness but a more distant divergence time. To address this question, 34 the ecological diversity of a fossil primate community from La Venta, Colombia, a Middle 35 Miocene platyrrhine community with phylogenetic diversity comparable to extant 36 platyrrhine communities but a relatively short time since divergence, was compared with 37 that of modern neotropical primate communities. -

An Extinct Monkey from Haiti and the Origins of the Greater Antillean Primates

An extinct monkey from Haiti and the origins of the Greater Antillean primates Siobhán B. Cookea,b,c,1, Alfred L. Rosenbergera,b,d,e, and Samuel Turveyf aGraduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016; bNew York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY 10016; cDepartment of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708; dDepartment of Anthropology and Archaeology, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY 11210; eDepartment of Mammalogy, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024; and fInstitute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London NW1 4RY, United Kingdom Edited* by Elwyn L. Simons, Duke University, Durham, NC, and approved December 30, 2010 (received for review June 29, 2010) A new extinct Late Quaternary platyrrhine from Haiti, Insulacebus fragment (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The latter preserves alveoli from toussaintiana, is described here from the most complete Caribbean left P4 to the right canine. subfossil primate dentition yet recorded, demonstrating the likely coexistence of two primate species on Hispaniola. Like other Carib- Etymology bean platyrrhines, I. toussaintiana exhibits primitive features resem- Insula (L.) means island, and cebus (Gr.) means monkey; The bling early Middle Miocene Patagonian fossils, reflecting an early species name, toussaintiana, is in honor of Toussainte Louverture derivation before the Amazonian community of modern New World (1743–1803), a Haitian hero and a founding father of the nation. anthropoids was configured. This, in combination with the young age of the fossils, provides a unique opportunity to examine a different Type Locality and Site Description parallel radiation of platyrrhines that survived into modern times, but The material was recovered in June 1984 from Late Quaternary ′ ′ is only distantly related to extant mainland forms. -

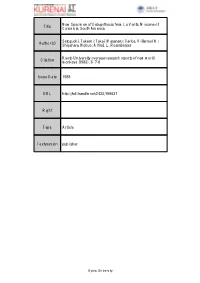

Title New Specimen of Cebupithecia From

New Specimen of Cebupithecia from La Venta, Miocene of Title Colombia, South America Setoguchi, Takeshi; Takai, Masanaru; Carlos, Villarroel A.; Author(s) Shigehara, Nobuo; Alfred, L. Rosenberger Kyoto University overseas research reports of new world Citation monkeys (1988), 6: 7-9 Issue Date 1988 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/199637 Right Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University 7 N ew Specimen of Cebupithecia from La Venta , Miocene of Colombia , South America Takeshi Takeshi SETOGUCHI, Masanaru TAKAI Primate Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Jnuyama City, Aichi 484, Japan Carlos Carlos VILLARROEL A., Department of Geology, Nation αl University Bogota 8, Colombia Nobuo SHIGEHARA, Department of Anatomy, .Dokkyo School of Medicine, Mibu, Tochigi Tochigi 321 ・02, Japan. & Alfred L. ROSENBERGER Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois at Chicago, Illinois Illinois 60680, US.A. SYSTEMATIC ACCOUNTS Cebupithecia Cebupithecia sarmientoi STIRON and SAVAGE, 1951 (Figure (Figure 1) Material: Material: IGM-KU 8602 (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Geologico ・Min eras [INGEOMINAS] -Kyoto University) ,a right maxilla with C and P2. Locality: Locality: Locality 9・86 ・B in the El Dinde area, probably within the Monkey Unit of the Honda Formation (FIELDS, 1959), in the Tatacoa desert, Huila Department, Republic of Colombia. Colombia. Age: Age: Middle Miocene , Friasian Land Mammal Age , 12 ・15 Myr. Description :必 though the upper canine of IGM-KU 8602 is of the almost same size and shape shape as the holotype of this species ) UCMP 38762, the anterior and the posterior blades are more sharply defined in the former than in the latter. 百ie vertical groove on the lingual face between the anterior blade and the central torus is deeper in the former. -

30 Tejedor.Pmd

Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, v.66, n.1, p.251-269, jan./mar.2008 ISSN 0365-4508 THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEOTROPICAL PRIMATES 1 (With 4 figures) MARCELO F. TEJEDOR 2 ABSTRACT: A significant event in the early evolution of Primates is the origin and radiation of anthropoids, with records in North Africa and Asia. The New World Primates, Infraorder Platyrrhini, have probably originated among these earliest anthropoids morphologically and temporally previous to the catarrhine/platyrrhine branching. The platyrrhine fossil record comes from distant regions in the Neotropics. The oldest are from the late Oligocene of Bolivia, with difficult taxonomic attribution. The two richest fossiliferous sites are located in the middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, and to the south in early to middle Miocene sites from the Argentine Patagonia and Chile. The absolute ages of these sedimentary deposits are ranging from 12 to 20 Ma, the oldest in Patagonia and Chile. These northern and southern regions have a remarkable taxonomic diversity and several extinct taxa certainly represent living clades. In addition, in younger sediments ranging from late Miocene through Pleistocene, three genera have been described for the Greater Antilles, two genera in eastern Brazil, and at least three forms for Río Acre. In general, the fossil record of South American primates sheds light on the old radiations of the Pitheciinae, Cebinae, and Atelinae. However, several taxa are still controversial. Key words: Neotropical Primates. Origin. Evolution. RESUMO: Origem e evolução dos primatas neotropicais. Um evento significativo durante o início da evolução dos primatas é a origem e a radiação dos antropóides, com registros no norte da África e da Ásia. -

Taxonomy of the Genus Brachyteles Spix, 1823 and Its Phylogenetic

MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Taxonomy of the genus Brachyteles Spix, 1823 and its phylogenetic position within the subfamily Atelinae Gray, 1825 José Eduardo Serrano Villavicencio São Paulo 2016 MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MASTOZOOLOGIA JOSÉ EDUARDO SERRANO VILLAVICENCIO Taxonomy of the genus Brachyteles Spix, 1823 and its phylogenetic position within the subfamily Atelinae Gray, 1825 Dissertação apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação do Museu de Zoologia da universidade de São Paulo para o obtenção de titulo de Mestre em Sistemática, Taxonomia Animal e Biodiversidade Orientador: Prof. Dr. Mario de Vivo São Paulo 2016 Ficha catalográfica Serrano-Villavicencio, José Eduardo Taxonomy of the genus Brachyteles Spix, 1823 and its phylogenetic position within the subfamily Atelinae Gray, 1825; orientador Mario de Vivo. – São Paulo, SP: 2016. 198 p.; 56 figs; 10 tabs. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Programa de Pós-graduação em Sistemática, Taxonomia Animal e Biodiversidade, Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, 2016. 1. Brachyteles, 2. Filogenia - Brachyteles, 3. Atelinae I. Vivo, Mario de. II. Título. Banca Examinadora _______________________________ ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Prof. Dr. Instituição: Instituição: Julgamento Julgamento: _______________________________ Prof. Dr. Mario de Vivo (Orientador) Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo ©Stephen Nash Con todo mi amor para Elisa y Juan que son mi razón para jamás desistir. Nunca terminaré de agradecer cada uno de sus sacrificios. Agradecimentos Aunque la gran mayoría del presente trabajo se encuentra redactado en inglés, quise tomarme la libertad de expresar mis agradecimientos más sinceros en mi lengua materna para no dejar ningún sentimiento al aire. En primer lugar, me gustaría agradecer a mi orientador Mario de Vivo quien se arriesgó a aceptar un desconocido biólogo peruano sin mayor experiencia. -

Stem Taxa, Homoplasy, Long Lineages, and the Phylogenetic Position of Dolichocebus

Journal of Human Evolution 59 (2010) 218e222 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol News and Views Stem taxa, homoplasy, long lineages, and the phylogenetic position of Dolichocebus Richard F. Kay a,*, John G. Fleagle b a Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA b Department of Anatomical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794-8081, USA article info identifying them as being members of a clade. In our analysis, a suite of derived anatomical features that are generally lacking in Article history: the Patagonian taxa unites all living, or crown, platyrrhines. Among Received 16 November 2009 other things, compared with the Patagonian taxa, crown platyr- Accepted 12 February 2010 rhines have a shorter rostrum, a more transversely arched palate, Keywords: more convergent orbits, reorganization of the arrangement of the Platyrrhini bones at pterion, larger, more transversely positioned premolar Phylogenetics metaconids, loss of molar hypoconulids and of a postentoconid Anthropoidea sulcus, and reduction of molar roots. It is the absence of the above- Molecular clocks listed derived features of crown platyrrhines in the Patagonian taxa that suggests each of them is a stem platyrrhine, and outside of the modern radiation. The Patagonian taxa may belong to a separate stem clade or they may be a paraphyletic group, one species of which may prove to be the sister to the most recent common In his reply to our recent paper (Kay et al., 2008) entitled “The ancestor of living platyrrhines. Either way, Dolichocebus, Trem- anatomy of Dolichocebus gaimanensis, a stem platyrrhine monkey acebus and the other less-well known Patagonian early Miocene from Argentina,” Rosenberger (2010: p.1) addresses a wide range of monkeys are stem platyrrhines.