Reflections on Some Major Lincolnshire Place-Names Part One: Algarkirk to Melton Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sabrina Times July 2007 Editorial Library This Issue Is a Short One and It's Late

E 17 July 2007 Severnside Branch SSaabbrriinnaa TTiimmeess Branch Organiser's Bit I have just reviewed my last piece for the newsletter and find I made a comment about how the weather would surely be better for our May fieldtrip. How wrong I was! Although the day before had been lovely, Sunday 13th May was very overcast and wet. The Cat's Back was not visible through the cloud but I was impressed by the number of members who turned out in such weather. It was great to see you all. Also, well done and thank you to Duncan who was able to offer us an alternative, lower route, avoiding the cloud if not the rain, and still filled the day with interesting Ever wonder where the exposures. “Sabrina” name comes Our trip to Flat Holm in June was fully booked; from? Here's your answer. as is the week’s trip to Kindrogan in July. Unlike One of a series of carved the Cat's Back trip, the weather for Flat Holm oak statues near the Old was good. It was an excellent day out, and I'd Railway Station, Tintern, like to thank Chris Lee for guiding us. it is dedicated to the Jan and Linda are running a shoestring trip to legend of the Celtic the Sierras in Central Spain in September. goddess, whose latinised There are still spaces on this. In addition to the name is Sabrina. The geology there are many medieval towns in the inset is of the signboard area to explore; not to mention Madrid. -

Treasure Annu Al Report 2005/6

TREASURE ANNUAL REPORT 2005/6 REPORT ANNUAL TREASURE TREASURE ANNUAL REPORT 2005/6 TREASURE ANNUAL REPORT 2005/6 Foreword 4 Introduction 6 Tables 7 List of contributors 10 Distribution maps of Treasure cases 14 Catalogue England 1. Artefacts A. Bronze Age 16 B. Iron Age 54 C. Roman 58 D. Early Medieval 72 E. Medieval 104 F. Post-Medieval 134 G. 18th–20th centuries and Undiagnostic 170 2. Coins A. Iron Age 184 B. Roman 188 C. Early Medieval 207 D. Medieval 209 E. Post-Medieval 215 Wales 220 Northern Ireland 231 References 232 Valuations 238 Index 243 Illustrations 269 Cover: Iron Age electrum torc (no. 82), c. 200–50 BC. Found in Newark, Nottinghamshire, by Mr M Richardson while metal-detecting in February 2005. CONTENTS 2 3 This is the eighth Annual Report to Parliament on I would also like to praise the contribution made Following a consultation by my Department we the operation of the Treasure Act 1996. Like its by the staff of the British Museum and the staff of transferred the administrative responsibilities for predecessors, it lists all the finds that were reported as the National Museum Wales. The Treasure process Treasure to the British Museum in March 2007. potential Treasure to the British Museum, the National requires input from their curators, conservators, The British Museum has recruited two full-time Museums & Galleries of Wales, and the Environment scientists and a central treasure registry, all of whom and one part-time post in order to deal with these and Heritage Service, Northern Ireland. This Report continue to achieve high standards of service despite additional responsibilities and both organisations contains details of 592 and 665 new cases reported an increased workload. -

![LINCOLN.] Farmers-Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2008/lincoln-farmers-continued-172008.webp)

LINCOLN.] Farmers-Continued

TltADES DIRlW'l;ORY.] 415 FAR [LINCOLN.] FARMERs-continued. Cottingham Edmund, Snarford, Market Coy D. Central Wingland, Wisbech Cook John Hall, Salmonby, Horncastle Rasen Coy J. Donington Spalding Cook Joseph, Owston ferry, Bawtry Cottingham Edwin, Snarford, Market Coy J. Epworth, Bawtry CookJosephWilliam,Kirton-in-Linusey Rasen Coy T. Fen, Gosberton, Spalding Cook Mrs. M. Nettleton, Caistor Cottingham Mrs. Elizabeth, West Craft J. Fen, Algarkirk, Spalding Cook R. Holton-le-Moor, Caistor Barkwith, Wragby Cragg D. Westborough, Grantham Cook T. West Ashby, Horncastle Cottingham H. Linwood, Blankney, Cragg J. Tydd St. Mary, Wisbech Cook W. Gayton-le-.Marsh, Alford Sleaford Cragg W. Sutton St. James, Wisbech Cook W. Hemingby, Horncastle Cottingham J.Scotter,Kirton-in-Lindsy Cram T. Burgh-in-the-Marsh, Boston Cook W. Tattershall, Boston Cottingham Mrs. M. Friesthorpe, Cramp ton J. Cow bit, Spalding Cook W. G. S. Upton, Gainsborough Market Rasen Crane Mrs. E. Moulton, Spalding Cooke B. Station rd. Postland,Crowland Cottrill B. N orthOwersby, MarketRasen Crane J. Ealand, Crow le, Bawtry Cooke E. Friskney Boston Coulam G. Withem, Alford Crane J. Quadring, Spalding Cooke H. Postland, Crowland Coulbeck W. & H. Cleethorpes, Great Crane W. Fleet, Wisbech Cooke James, Pode hole, Spalding Grimsby Cranidge E. Crowle, Bawtry Cooke John, North Thorsby, Louth Coulbeck R. Ashby, Brigg Cranidge John, Crowle, Bawtry Cooke John, Wainfleet, Boston CoulbeckR.Barrow-on-Humber,Ulceby Cranidge Jonathan, Crowle, Bawtry Cooke John, Wyberton, Boston Coulbeck W. Apple by, Brigg Cranidge J osepb Margrave,. Crowle, CookeR. Navenby, Grantham Coulbeck W. Broughton, Brigg Bawtry Cooke Robert D. Everard house, Post- Coulman E. Belton, Bawtry Cranidge P. -

Lincolnshire.. Far 683

TRADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE.. FAR 683 Darnell William, Bardney, Lincoln Dawson William, Nettleton, Caistor Dickinson Thomas, Friskney, Boston Darnill George, Orby, Boston Dawson Wm. Skeldyke, Kirton, Boston DickinsonW.Sandpits,Westhorpe,Spaldg Darnill Jn. Jack, Grainthorpe, Grimsby Dawson William, Union road, Caistor Dickinson Wm. Westhorpe, Spalding Daubeny Jabez, North Kyme, Lincoln Day Edward Jas. Messingham, Brigg Dickson Frederick, Tumby, Boston Dauber John William, Ruckland, Louth Day John, Wood Enderby, Boston Diggle E. Suttun St. Edmunds, Wisbech Daubney C. Hagworthingham, Spilsby Day John Wm. Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Diggle J.H. Loosegate rd. Moultn.Spldng Dau bney Charles, Leake, Boston Day Ro bt. Scotter Hig hfield, Ki rtonLindsy DiggleJ ohnHarber, j u n. Moulton, Spaldng Daubney Charles, jun. Leake, Boston Day Robert,Scotterthorpe,KirtonLindsy Diggle Thos. Ewerby Thorpe, Sleaford Daubney George, Belchford, Horncastle Day Thomas, Church street, Caistor Diggle Thomas, Weston, Spalding Daubney H.Manor frm.Canwick, Lincoln Day William, Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Dilworth James, Horse Shoe rd.Spaldmg Daubney Henry, Wyberton, Boston Day Wm. Cotehouses, 0 wston Ferry Dimbleby W .BishopNortn. Kirtn.Lindsy Daubney James, Navenby S.O Dean Arthur W. Dowsby, Falkingham Dinnis Thomas, Anderby, Alford Daulton Austin, West Keal, Spilsby Dean Edward, Algarkirk, Boston Dinnison Thomas Hy. Burr la. Spalding Daulton Henry, Bilsby, Alford Dean John, Drayton, Swineshead,Boston Dinsdale John, Nth.Killingholme, Ulceby Daulton Jesse, The Grange, East Keal Dean John, Drove end, Wisbech Dion Frederick, Sibsey, Boston Coates, East Keal, Spilsby Dean John, Goxhill, Hull Dion James, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Joseph, Keal Coates, Spilsby Dean John Chas. Drove end, Wisbech Dion Jesse, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Thomas, East Kirkby, Spilsby Dean John Hy. -

Memoirs of an Infantry Auctioneer

Memoirs of an Infantry Auctioneer Selling G.B. Read’s Champion Bullock at Horncastle Fat Stock Show. R. H. Bell, Mareham Grange 4th Lincolns at Ripon 1939-1940: Back row: Robert Bell, Gordon Spratt, John Gaunt, ?, Tony Bell; Front row: Charles Spratt, Jack Wynn, ?. 1996 Memoirs of an Infantry Auctioneer R. H. Bell, Mareham Grange 1996 1 Copyright © 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, whether recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the copyright holder. Printed by Cupit Print, The Ropewalk, Horncastle, Lincolnshire, LN9 5ED 2 Introduction by Robert Lawrence Hay Bell aving the same names as his father (and same initials as his grandfather) it was perhaps inevitable that Robert Hay Bell would follow his father Hinto the family business of Land Agency. But by the tender age of 28 he had experienced more than many of us see in the whole of our lives. He was born during the First World War at Lansdowne, Spilsby Road, Horncastle, the fourth child of six and the eldest son. His father was an auctioneer and land agent and came from a family of factors or land agents who had started in Perthshire. His great grandfather, George Bell, had secured the post of resident land agent on the Revesby Estate in 1842 bringing his family to Lincolnshire. His quick open mind fostered an interest in a wide variety of subjects including, centrally, agriculture. It was his perseverance that kept Horncastle cattle market going (perhaps beyond its natural life). -

Horncastle, Fulletby & West Ashby

Lincolnshire Walks Be a responsible walker Walk Information Introduction Please remember the countryside is a place where people live Horncastle, Fulletby Walk Location: Horncastle lies 35km (22 miles) Horncastle is an attractive market town lying at the south-west foot and work and where wildlife makes its home. To protect the of the Lincolnshire Wolds and noted for its antique shops. The east of Lincoln on the A158. Lincolnshire countryside for other visitors please respect it and & West Ashby town is located where the Rivers Bain and Waring meet, and on the on every visit follow the Countryside Code. Thank you. Starting point: The Market Place, Horncastle site of the Roman fort or Bannovallum. LN9 5JQ. Grid reference TF 258 696. • Be safe - plan ahead and follow any signs Horncastle means ‘the Roman town on a horn-shaped piece of land’, • Leave gates and property as you find them Parking: Pay and Display car parks are located at The the Old English ‘Horna’ is a projecting horn-shaped piece of land, • Protect plants and animals, and take litter home Bain (Tesco) and St Lawrence Street, Horncastle. especially one formed in a river bend. • Keep dogs under close control • Consider other people Public Transport: The Interconnect 6 bus service operates This walk follows part of the Viking Way, the long distance footpath between Lincoln and Skegness and stopping in Horncastle. For between the Humber and Rutland Water, to gently ascend into the Most of all enjoy your visit to the further information and times call the Traveline on 0871 2002233 Lincolnshire Wolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and Lincolnshire countryside or visit www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/busrailtravel or the village of Fulletby. -

Lincoln in the Viking Age: a 'Town' in Context

Lincoln in the Viking Age: A 'Town' in Context Aleida Tessa Ten Harke! A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield March 2010 Volume 1 Paginated blank pages are scanned as found in original thesis No information • • • IS missing ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of Lincoln in the period c. 870-1000 AD. Traditional approaches to urban settlements often focus on chronology, and treat towns in isolation from their surrounding regions. Taking Lincoln as a case study, this PhD research, in contrast, analyses the identities of the settlement and its inhabitants from a regional perspective, focusing on the historic region of Lindsey, and places it in the context of the Scandinavian settlement. Developing an integrated and interdisciplinary approach that can be applied to datasets from different regions and time periods, this thesis analyses four categories of material culture - funerary deposits, coinage, metalwork and pottery - each of which occur in significant numbers inside and outside Lincoln. Chapter 1 summarises previous work on late Anglo-Saxon towns and introduces the approach adopted in this thesis. Chapter 2 provides a discussion of Lincoln's development during the Anglo-Saxon period, and introduces the datasets. Highlighting problems encountered during past investigations, this chapter also discusses the main methodological considerations relevant to the wide range of different categories of material culture that stand central to this thesis, which are retrieved through a combination of intrusive and non-intrusive methods under varying circumstances. Chapters 3-6 focus on funerary deposits, coinage, metalwork and pottery respectively, through analysis of distribution patterns and the impact of changes in production processes on the identity of Lincoln and its inhabitants. -

Our Resource Is the Gospel, and Our Aim Is Simple;

Bolingbroke Deanery GGr raappeeVViinnee MAY 2016 ISSUE 479 • Mission Statement The Diocese of Lincoln is called by God to faithful worship, confident discipleship and joyful service. • Vision Statement To be a healthy, vibrant and sustainable church, transforming lives in Greater Lincolnshire 50p 1 Bishop’s Letter Dear Friends, Many of us will have experienced moments of awful isolation in our lives, or of panic, or of sheer joy. The range of situations, and of emotions, to which we can be exposed is huge. These things help to form the richness of human living. But in themselves they can sometimes be immensely difficult to handle. Jesus’ promise was to be with his friends. Although they experienced the crushing sadness of his death, and the huge sense of betrayal that most of them felt in terms of their own abandonment of him, they also experienced the joy of his resurrection and the happiness of new times spent with him. They would naturally have understood that his promise to ‘be with them’ meant that he would not physically leave them. However, what Jesus meant when he said that they would not be left on their own was that the Holy Spirit would always be with them. It is the Spirit, the third Person of the Holy Trinity, that we celebrate during the month of May. Jesus is taken from us, body and all, but the Holy Spirit is poured out for us and on to us. The Feast of the Holy Spirit is Pentecost. It happens at the end of Eastertide, and thus marks the very last transition that began weeks before when, on Ash Wednesday, we entered the wilderness in preparation for Holy Week and Eastertide to come. -

Wilsthorpe Road, Braceborough

Wilsthorpe Road, Braceborough 4 Bedrooms, Detached Bungalow Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 4NX Offers In Excess Of £600,000 | For Sale 4 Bedrooms, Detached Bungalow Wilsthorpe Road, Braceborough Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 4NX Offers In Excess Of £600,000 | For Sale Features Four Bedroomed Detached Family This immaculate detached bungalow is situated on the edge of the village of Bungalow Braceborough with stunning open countryside views to the front and side of the property. Church View is set back from the road with ample off road parking to the Open Countryside Views to the front of the property with double garaging. This spacious family home offers bright Front and Side. living space over a large area. Pretty Village Location The accommodation comprises of a large living room with a bay fronted window to Living Room with Wood Burner the front and patio door to the side overlooking country views and a log burning stove. A large well equipped kitchen breakfast, separate dining room, study, long Dining Room hallway leading to master bedroom with en suite shower room, three further Kitchen/Breakfast Room bedrooms and family bathroom. Family Bathroom, Shower Room to Outside, the gardens to the front and side are low maintenance with a tarmac Master Bedroom driveway leading to a double garage. To the rear is a well maintained garden with Four Bedrooms & Study patio area and vegetable patch. There are borders with mature trees and shrubs. Gardens to the Front, Side and Rear. Re-locating buyers with Having 14 offices across London Important we would like to inform prospecti ve purchasers that these sales particul ars have been prepared as a general guide onl y. -

Flat Holm Island

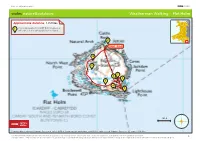

bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles 1 This walk begins in Cardiff Bay where you will catch the boat across to the island. 2 Start / End 10 9 7 8 6 3 4 5 N 500 ft W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to the TV programme only. Routes and conditions may have changed since the programme was made. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check weather conditions before heading out. 1 bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles A race against the tide to look at wartime relics and a stunning lighthouse on this beautiful island in the Bristol Channel. 1. The Cardiff Bay Barrage 4. Flat Holm Lighthouse This is where you will catch the boat to the The first light on the island was a simple island. The Barrage lies across the mouth brazier mounted on a wooden frame, which of Cardiff Bay between Queen Alexandra stood on the high eastern part of the island. Dock and Penarth Head and was one of The construction of a tower lighthouse with the largest civil engineering projects in lantern light was finished in 1737. Europe during the 1990s. Today it’s solar powered and the light from its three 100 watt bulbs can be seen up to 16 miles away. -

July 2007 Volume XXVI1 Issue

Fete Volume XXVI1 Issue July 2007 mistakes increases. “Is that possible?” I For the parishes of TSUNAMI BOOK APPEAL hear you ask. Careby, with Aunby & You will all recall the tsunami Holywell, Castle Bytham, disaster when so many people of all Creeton with Counthorpe and Little Bytham. nat io nalit ies lo st so m u ch - LOCAL G OVERNMENT possessions, family and friends - even W it h Lit tle Bytham’s Par ish Editor - Peter Cox, 23 High Street, Castle Bytham. NG33 their lives Council now being formed, the local 4RZ Tel 410457 (E-Mail: In Sri Lanka, 500 miles of coastal elections are complete. Five people [email protected] were nominated, leaving two vacancies Representatives - region were devastated and everything Careby (with Aunby & lost. Much effort has gone into to be filled.Those nominated were:- Holywell) - Judith Smith John Sharpe Thistlecroft, Careby PE9 4EA repairing the physical and material Tel 410420 losses and damage but one small area W enda Murphy Castle Bytham - Diana Hill, 6, which needs help is children’s books. Peter Jones Regal Gardens, Castle Bytham Creeton (with Counthorpe)- Sri Lanka has one of the highest Diana Harris Anne Garbutt, 2, Brownlow Farm literacy rates in the world so the lack Kirstie Bland Cottages, Creeton. Tel: 410563 Little Bytham:- Sheila Jones, Hill of books has hit the children there View, Station Road, Little particularly hard. So can we help? If W HEELIE BINS Bytham Tel 410232 your children have grown up why not I think the greatest problem with Hon. Treasurer & Distribution - Geoff Clapinson, donate the books they have finished wheelie bins, generally, is difficulty in 17 Cumberland Gardens, Castle with or if they are still young and under standing w hat go es w her e. -

The Provincial Priory Lincolnshire

THE MALTA DEGREE The Provincial Priory The historic “Knights of the Order of St John of of Jerusalem” (Knights Hospitaller) were founded in Jerusalem during the first Crusade, about the year 1099, by the association of many pious Knights with the Lincolnshire Brothers of St John’s Hospital, which had been founded earlier that same century, for the relief of pilgrims travelling to worship at the Holy Sepulchre. INTRODUCTION In Masonic terms, the Malta Degree is conferred on Candidates who have already been Installed as Knights THE ORDER of KNIGHTS TEMPLAR Templar. The regalia and ceremony are very different from that of Knights Templar Freemasonry as the Malta The Provincial Prior of Lincolnshire, Malcom Bilton hopes degree is in fact a separate Sovereign Order; hence the you will find this leaflet interesting and informative. It is an full name of the Great Priory being “The Great Priory of introduction to the Masonic and Military Orders of the The United Religious, Military and Masonic Orders of The Temple and of St John of Jerusalem, Palestine, Rhodes Temple and of St John of Jerusalem, Palestine, Rhodes and Malta, commonly known as the "United Orders", or and Malta of England and Wales and its Provinces simply “KT”. They are beautiful Christian masonic orders Overseas”. Knight Reginald Brittan with a rich and colourful history and have flourished in in Malta regalia Lincolnshire since 1879. The Province now consists of 9 The ceremony is based on the movement of the Knights Hospitaller from their units, known as Preceptories, situated within the old inception in Jerusalem, to their settling on the Island of Malta in 1522 (having County boundary of Lincolnshire.