Pavel Kohout's Play Makbeth and Its Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visione Del Mondo

Weltanschauung - Visione del mondo Art Forum Würth Capena 14.09.09 – 07.08.10 Opere e testi di: Kofi Annan, Louise Bourgeois, Abdellatif Laâbi, Imre Bukta, Saul Bellow, John Nixon, Bei Dao, Xu Bing, Branko Ruzic, Richard von Weizsäcker, Anselm Kiefer, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Marcos Benjamin, Twins Seven Seven, Paavo Haavikko, Hic sunt leones, Nelson Mandela, Kyung Hwan Oh, Jean Baudrillard, Huang Yong Ping, Nagib Machfus, Inge Thiess-Böttner, Guido Ceronetti, Richard Long, Yasar Kemal, Igor Kopystiansky, Imre Kertèsz, Svetlana Kopystiansky, Kazuo Katase, Milan Kundera, Frederich William Ayer, Günter Uecker, Durs Grünbein, Mehmed Zaimovic, Enzo Cucchi, Vera Pavlova, Franz-Erhard Walther, Charles D. Simic, Horacio Sapere, Susan Sontag, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, George Steiner, Nicole Guiraud, Bernard Noël, Mattia Moreni, George Tabori, Richard Killeen, Abdourahman A. Waberi, Roser Bru, Doris Runge, Grazina Didelyte, Gérard Titus-Carmel, Edoardo Sanguineti, Mimmo Rotella, Adam Zagajewski, Piero Gilardi, Günter Grass, Anise Koltz, Moritz Ney, Lavinia Greenlaw, Xico Chaves, Liliane Welch, Fátima Martini, Dario Fo, Tom Wesselmann, Ernesto Tatafiore, Emmanuel B. Dongala, Olavi Lanu, Martin Walser, Roman Opalka, Kostas Koutsourelis, Emilio Vedova, Dalai Lama, Gino Gorza, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Robert Indiana, Nadine Gordimer, Efiaimbelo, Les Murray, Arthur Stoll, Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, Boris Orlov, Carlos Fuentes, Klaus Staeck, Alì Renani, Wolfang Leber, Alì Aramideh Ahar, Sogyal Rinpoche, Ulrike Rosembach, Andrea Zanzotto, Adriena Simotova, Jürgen -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Cze0s, Hit Dubeek, Hint at CIA Links

Cze0s, Hit Dubeek, Hint at CIA Links • By Dusko Doder The program included schedule advisories or guid- „.iisshington Post Porelirn Service the ominous-sounding state- ance papers. PRAGUE, March 10 — ment that alle ged "con- The radio, which was once Czechoslovakia's govern- nectfons of the opposition financed by the CIA, broad- ment launched a major at- people will be judged in casts daily to Czechoslova- tack On former Communist forums other than this" in- Ida, Hungary, Romania, Po- Party = elader Alexander terview. land and Bulgaria. It often Dtbeek and his supporters Political observers here uses material smuggled out tonight, strongly hinting interpreted the public at- of Communist countries to that they' have maintained tack on the leaders of the the West links with the U.S. Central "Prague Spring" — the brief The only clear reference intelligence Agency. period of liberalizing re. to Dubcek in the papers The 'charges were made forms that Dubcek intro- shown on the screen was a during a 45-minate televi- duced in 1968 before it was letter he wrote 0after. the sion interview with Capt. crsuhed by the Soviet-led in- death of Josef Smrkovsky, a Pavel Minarek, a Czech' in- vasion — as a clear warning prominent leader of the telligente agent who infil- against dissident activities "Prague Spring." trated the TJ.S.-operated Ra- between now and next The thrust of Minarik's re- dio Free Europe. The inter- month's Communist Party marks was that RFE is still view, broadcast live here, congress. a branch of the CIA and was also carried over Inter- These observers said that that Czechoslovak dissidents vision, the network linking theer are no indications that were knowingly working for 111 Soviet-bloc countries. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

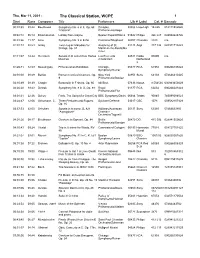

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Mar 11, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 39:42 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Dresden 03086 LaserLight 15 825 018111582520 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Kegel 00:42:1205:14 Khachaturian Lullaby from Gayne Boston Pops/Williams 01542 Philips 426 247 028942624726 00:48:2611:17 Arne Symphony No. 3 in E flat Cantilena/Shepherd 00957 Chandos 8403 n/a 01:01:13 08:54 Grieg Two Elegiac Melodies for Academy of St. 01144 Argo 417 132 028941713223 Strings, Op. 34 Martin-in-the-Fields/Ma rriner 01:11:0714:24 Reincken Sonata in D minor from Hortus Les Eléments 04531 Radio 93009 n/a Musicus Amsterdam Netherland s 01:26:3132:59 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Chicago 05877 RCA 61958 090266195824 Symphony/Reiner 02:01:00 08:49 Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture, Op. New York 02950 Sony 64103 074646410325 9 Philharmonic/Boulez 02:10:4908:39 Chopin Barcarolle in F sharp, Op. 60 Idil Biret 07436 Naxos 8.554536 636943453629 02:20:2839:23 Dvorak Symphony No. 8 in G, Op. 88 Royal 01377 RCA 60234 090266023424 Philharmonic/Flor 03:01:2122:26 Delius Paris, The Song of a Great City BBC Symphony/Davis 06684 Teldec 90845 745099084523 03:24:4712:06 Schumann, C. Three Preludes and Fugues, Sylviane Deferne 03017 CBC 1078 059582107829 Op. 16 03:37:53 22:03 Schubert Sonata in A minor, D. 821 Williams/Australian 05137 Sony 63385 07464633850 "Arpeggione" Chamber Orchestra/Tognetti 04:01:2608:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. -

Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre

Masters i Constructing the Sensorium: Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre A dissertation submitted by Paul Masters in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama Tufts University May 2016 Adviser: Natalya Baldyga Masters ii Abstract: Associated with a broad range of theatrical events and experiences, the term immersive has become synonymous with an experiential, spectacle-laden brand of contemporary theatre. From large-scale productions such as Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More (2008, 2011) to small-scale and customizable experiences (Third Rail Projects, Shunt, and dreamthinkspeak), marketing campaigns and critical reviews cite immersion as both a descriptive and prescriptive term. Examining technologies and conventions drawn from a range of so-called immersive events, this project asks how these productions refract and replicate the technological and ideological constructs of the digital age. Traversing disciplines such as posthumanism, contemporary art, and gaming studies, immersion represents an extension of a cultural landscape obsessed with simulated realities and self-surveillance. As an aesthetic, immersive events rely on sensual experiences, narrative agency, and media installations to convey the presence and atmosphere of otherworldly spaces. By turns haunting, visceral, and seductive spheres of interaction, these theatres also engage in a neoliberal project: one that pretends to greater freedoms than traditional theater while delimiting freedom and concealing the boundaries -

The Tragedy of Macbeth William Shakespeare 1564–1616

3HAKESPEARean DrAMA The TRAGedy of Macbeth Drama by William ShakESPEARE READING 2B COMPARe and CONTRAST the similarities and VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML12-346A DIFFERENCes in classical plaYs with their modern day noVel, plaY, or film versions. 4 EVALUAte how THE STRUCTURe and elements of drAMA -EET the AUTHOR CHANGe in the wORKs of British DRAMAtists across literARy periods. William ShakESPEARe 1564–1616 In 1592—the first time William TOAST of the TOwn In 1594, Shakespeare Shakespeare was recognized as an actor, joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the poet, and playwright—rival dramatist most prestigious theater company in Robert Greene referred to him as an England. A measure of their success was DId You know? “upstart crow.” Greene was probably that the theater company frequently jealous. Audiences had already begun to performed before Queen Elizabeth I and William ShakESPEARe . notice the young Shakespeare’s promise. her court. In 1599, they were also able to • is oFten rEFERRed To as Of course, they couldn’t have foreseen purchase and rebuild a theater across the “the Bard”—an ancienT Celtic term for a poet that in time he would be considered the Thames called the Globe. greatest writer in the English language. who composed songs The company’s domination of the ABOUT heroes. Stage-Struck Shakespeare probably London theater scene continued • INTRODUCed more than arrived in London and began his career after Elizabeth’s Scottish cousin 1,700 new wORds inTo in the late 1580s. He left his wife, Anne James succeeded her in 1603. James the English languagE. Hathaway, and their three children behind became the patron, or chief sponsor, • has had his work in Stratford. -

CZECHOSLOVAK NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED by the COUNCIL of FREE CZECHOSLOVAKIA 420 East 71 Street, New York, NY 10021

CZECHOSLOVAK NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY THE COUNCIL OF FREE CZECHOSLOVAKIA 420 East 71 Street, New York, NY 10021 Vol. IV, No. 9/10 (36/37) September-October 1979 CONTENTS The Kohout Case ............................................ p. 1 Religion under Communism .................... p. 3 Foreign Trade Problems ........................ p. 3 Czech Literature Today .............................. p. 6 Dissidents Convicted in Prague . p. 8 Council's Thanks to the Pope ... p. 11 THE KOHOUT CASE The Czech writer Pavel Kohout has been stripped of his Czechoslovak citizen ship, he was informed by the Czechoslovak embassy in Vienna on October 8. Kohout, author of Poor Murderer and the model for the hero of Tom Stoppard's Dogg's Hamlet, Cahoot's Macbeth, left his native Czechoslovakia with his wife Jelena last October 28 to serve as director of the Burgtheater in Vienna. The Czechoslovak authorities granted them a one-year exit visa on the understanding that Kohout would avoid political activity while he was abroad. On his arrival in Vienna Kohout stated that, while he did not renounce anything he had said or writ ten in Czechoslovakia, he preferred to speak out on political matters in his home land. While he was abroad, he said,.he looked forward to attending the opening of productions of some of his plays and to the publication of his novel The Hangwoman (banned in Czechoslovakia, but to be put out in English by G. P. Putnam's Sons early next year). On October 4, three weeks before the expiry of their visa, Kohout and his wife drove to the Austro-Czechoslovak border at Nová Bystřice. -

The ESSE Messenger

The ESSE Messenger A Publication of ESSE (The European Society for the Study of English Vol. 25-2 Winter 2016 ISSN 2518-3567 All material published in the ESSE Messenger is © Copyright of ESSE and of individual contributors, unless otherwise stated. Requests for permissions to reproduce such material should be addressed to the Editor. Editor: Dr. Adrian Radu Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Faculty of Letters Department of English Str. Horea nr. 31 400202 Cluj-Napoca Romania Email address: [email protected] Cover illustration: Gower Memorial to Shakespeare, Stratford-upon-Avon This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Picture credit: Immanuel Giel Contents Shakespeare Lives 5 Europe, like Hamlet; or, Hamlet as a mousetrap 5 J. Manuel Barbeito Varela 5 Star-crossed Lovers in Sarajevo in 2002 14 Ifeta Čirić-Fazlija 14 Shakespeare on Screen 26 José Ramón Díaz Fernández 26 The Interaction of Fate and Free Will in Shakespeare’s Hamlet 27 Özge Özkan Gürcü 27 The Relationship between Literature and Popular Fiction in Shakespeare’s Richard III 37 Jelena Pataki 37 Re-thinking Hamlet in the 21st Century 49 Ana Penjak 49 Reviews 61 Mark Sebba, Shahrzad Mahootian and Carla Jonsson (eds.), Language Mixing and Code-Switching in Writing: Approaches to Mixed-Language Written Discourse (New York & London: Routledge, 2014). 61 Bernard De Meyer and Neil Ten Kortenaar (eds.), The Changing Face of African Literature / Les nouveaux visages de la litterature africaine (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2009). 63 Derek Hand, A History of the Irish Novel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). -

Language, Memory, and Exile in the Writing of Milan Kundera

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-13-2016 Language, Memory, and Exile in the Writing of Milan Kundera Christopher Michael McCauley Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McCauley, Christopher Michael, "Language, Memory, and Exile in the Writing of Milan Kundera" (2016). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3047. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3041 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Language, Memory, and Exile in the Writing of Milan Kundera by Christopher Michael McCauley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in French Thesis Committee: Annabelle Dolidon, Chair Jennifer Perlmutter Gina Greco Portland State University 2016 © 2016 Christopher Michael McCauley i Abstract During the twentieth century, the former Czechoslovakia was at the forefront of Communist takeover and control. Soviet influence regulated all aspects of life in the country. As a result, many well-known political figures, writers, and artists were forced to flee the country in order to evade imprisonment or death. One of the more notable examples is the writer Milan Kundera, who fled to France in 1975. Once in France, the notion of exile became a prominent theme in his writing as he sought to expose the political situation of his country to the western world—one of the main reasons why he chose to publish his work in French rather than in Czech. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Francophonie and Human Rights: Diasporic Networks Narrate Social Suffering Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sr5c9kj Author Livescu, Simona Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Francophonie and Human Rights: Diasporic Networks Narrate Social Suffering A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Simona Liliana Livescu 2013 © Copyright by Simona Liliana Livescu 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Francophonie and Human Rights: Diasporic Networks Narrate Social Suffering by Simona Liliana Livescu Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Efrain Kristal, Co-Chair Professor Suzanne E. Slyomovics, Co-Chair This dissertation explores exilic human rights literature as the literary genre encompassing under its aegis thematic and textual concerns and characteristics contiguous with dissident literature, resistance literature, postcolonial literature, and feminist literature. Departing from the ethics of recognition advanced by literary critics Kay Schaffer and Sidonie Smith, my study explores how human rights and narrated lives generate larger discursive practices and how, in their fight for justice, diasporic intellectual networks in France debate ideas, oppressive institutions, cultural practices, Arab and European Enlightenment legacies, different traditions of philosophical and religious principles, and global transformations. I conceptualize the term francité d’urgence , definitory to the literary work and intellectual trajectories of those writers who, forced by the difficult political situation in their home countries, make a paradoxical aesthetic use of France, its ii territory, or its language to promote local, regional, and global social justice via broader audiences. -

Günter Grass Et La France

Günter Grass et la France Pour Étienne François S’il fallait nommer un seul élément significatif du lien entre Günter Grass et la France, ce serait celui-ci : c’est « chez nous » — on admettra quelque autodérision dans cette exclamation chauvine —, c’est « chez nous » donc, dans la capitale française, que Günter Grass a écrit Le Tambour, ce chef-d’œuvre de roman tonitruant qui, quarante-six ans après sa paru- tion (en 1959), reste l’un des plus importants romans allemands de l’après-guerre. L’épisode parisien occupe assurément une place à part dans les souve- nirs personnels de l’écrivain, qui l’évoque volontiers dans les nombreux essais d’auto-interprétation auxquels il se livre régulièrement, par exemple sa « Rétrospective sur Le Tambour ou l’Auteur comme témoin suspect » de 1973, ou encore dans les pages consacrées aux années 1956-1958 dans sa chronique très personnelle du XXe siècle, Mon siècle (1999). Encore aujourd’hui, dans l’autobiographie de sa jeunesse et de sa propre genèse comme écrivain qu’il serait en train de préparer et qui devrait être publiée en 2006, comme il l’a révélé dans la presse, le prix Nobel de littérature 1999 terminerait le récit de ses années d’apprentissage précisément sur ce tournant majeur, mettant l’accent sur la période parisienne précédant la consécration littéraire. Il ne fait donc aucun doute que, de l’aveu même de l’écrivain, les années parisiennes ont joué un rôle déterminant dans son devenir et ont contribué à façonner dans le long terme sa vision du monde en général (et bien sûr de la France en particulier).