Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

Dedicated J. A. B. Marshall, Esq. Members of the Lansdown Cricket

D E D I C A T E D J A B . M . ARSHAL L, ESQ HE LA SDOWN C I KE C MEMBERS OF T N R C T LUB, B Y ONE OF THEIR OLD EST MEMB ERS A ND SINCERE FRIEND , THE U HO A T R . PRE FACE T H E S E C O N D E D I T I O N. THIS Edition is greatly improved by various additions and corrections, for which we gratefully o ur . acknowledge obligations to the Rev. R . T . A King and Mr . Haygarth, as also once more . A . l . to Mr Bass and Mr. Wha t e ey Of Burton For our practical instructions on Bowling, Batting, i of and Field ng, the first players the day have o n t he been consulted, each point in which he respectively excelled . More discoveries have also been made illustrative o f the origin and early history o f Cricket and we trust nothing is want ing t o maintain the high character now accorded ” A u tho to the Cricket Field, as the Standard on f rity every part o ou r National Ga me . M a 1 8 . 1 85 4 y, . PRE FACE T H F E I R S T E D I T I O N. THE following pages are devoted to the history f and the science o o ur National Game . Isaac Walton has added a charm to the Rod and Line ; ‘ a nd Col. Hawker to the Dog and the Gun ; Nimrod and Harry Hieover to the Hunting : Field but, the Cricket Field is to this day untrodden ground . -

A Unique Experience with Albion Journeys

2020 Departures 2020 Departures A unique experience with Albion Journeys The Tudors & Stuarts in London Fenton House 4 to 11 May, 2020 - 8 Day Itinerary Sutton House $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy Eastbury Manor House The Charterhouse St Paul’s Cathedral London’s skyline today is characterised by modern high-rise Covent Garden Tower of London Banqueting House Westminster Abbey The Globe Theatre towers, but look hard and you can still see traces of its early Chelsea Physic Garden Syon Park history. The Tudor and Stuart monarchs collectively ruled Britain for over 200 years and this time was highly influential Ham House on the city’s architecture. We discover Sir Christopher Wren’s rebuilding of the city’s churches after the Great Fire of London along with visiting magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral. We also travel to the capital’s outskirts to find impressive Tudor houses waiting to be rediscovered. Kent Castles & Coasts 5 to 13 May, 2020 - 9 Day Itinerary $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy The romantic county of Kent offers a multitude of historic Windsor Castle LONDON Leeds Castle Margate treasures, from enchanting castles and stately homes to Down House imaginative gardens and delightful coastal towns. On this Chartwell Sandwich captivating break we learn about Kent’s role in shaping Hever Castle Canterbury Ightham Mote Godinton House English history, and discover some of its famous residents Sissinghurst Castle Garden such as Ann Boleyn, Charles Dickens and Winston Churchill. In Bodiam Castle a county famed for its castles, we also explore historic Hever and impressive Leeds Castle. -

The Quest for the Historical Hooker by JOHN Booty T Is Questionable to What Degree the Historian Or Biographer Can I Recover and Represent a Person out of the Past

The Quest for the Historical Hooker BY JOHN BooTY T is questionable to what degree the historian or biographer can I recover and represent a person out of the past. The task may be one of great difficulty when there is a wealth of material, as is true with regard to John Henry Newman. But the task may be infinitely more difficult where there is a scarcity of evidence, as is true with regard to William Shakespeare. In the quest for the historical Hooker we encounter a moderate amount of material, but we are also left with gaps and, as we now realize, we are confronted by some conflicting evidence, requiring the use of careful judgment. We begin with certain indisputable facts concerning Richard Hooker's life, facts which can be verified by reference to documents which the historian can examine and rely upon. 1 Hooker was born in 1554 at Heavitree in Devonshire of parents who were prominent in their locality but by no means wealthy. With the assistance of an uncle, the young Hooker was educated first at a grammar school in Exeter and then, under the patronage of John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury, entered Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Subsequently he became an instructor in the University, was made a fellow of his college and was ordained to the ministry of the Church of England. There he remained, delivering the Hebrew lecture from 1579 until he departed from Oxford in 1584. Three facts concerning his time at the University are worth noting. The first is that he became the tutor of George Cranmer, whose father was a nephew of the famous Archbishop, and of Edwin Sandys, son of the Archbishop of York who became Hooker's patron after the death of Jewel in 1571. -

Victorian England Week Twenty One the Victorian Circle: Family, Friends Wed April 3, 2019 Institute for the Study of Western Civilization

Victorian England Week Twenty One The Victorian Circle: Family, Friends Wed April 3, 2019 Institute for the Study of Western Civilization ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Victoria and Her Ministers ThursdayApril 4, 2019 THE CHILDREN (9 born 1840-1857) ThursdayApril 4, 2019 ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Victoria Albert Edward (Bertie, King Ed VII) Alice Alfred Helena Louise Arthur Leopold Beatrice ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Queen Victoria with Princess Victoria, her first-born child. (1840-1901) ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Albert and Vicky ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Princess Victoria 1840-1901 ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1858 Marriage of eldest daughter Princess Victoria (Vicky) to “Fritz”, King Fred III of Prussia Albert and Victoria adored him. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Princess Victoria (Queen of Prussia) Frederick III and two of their children. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Queen Victoria with her first grandchild (Jan, 1858) Wilhelm, future Kaiser Wilhelm II ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Queen Victoria and Vicky, the longest, most continuous, most intense relationship of all her children. 5,000 letters, 60 years. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Little baby Bertie with sister Vickie ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Albert, Edward (Bertie) Prince of Wales age 5 in 1846 1841-1910) ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1860 18 year old Prince of Wales goes to Canada and the USA ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1860 Prince of Wales touring the USA and Canada (Niagara Falls) immensely popular, able to laugh and engage the crowds. They loved him. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 His closest friend in the whole world was his sister Alice to whom he could confide anything. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1861 Bertie’s Fall: An actress, Nellie Clifden 6 Sept Curragh N. -

The Rees and Carrington Extracts

THE REES AND CARRINGTON EXTRACTS CUMULATIVE INDEX – PEOPLE, PLACES AND THINGS – TO 1936 (INCLUSIVE) This index has been compiled straight from the text of the ‘Extracts’ (from January 1914 onwards, these include the ‘Rees Extracts’. – in the Index we have differentiated between them by using the same date conventions as in the text – black date for Carrington, Red date for Rees). In listing the movements, particularly of Kipling and his family, it is not always clear when who went where and when. Thus, “R. to Academy dinner” clearly refers to Kipling himself going alone to the dinner (as, indeed would have been the case – it was, in the 1890s, a men-only affair). But “Amusing dinner, Mr. Rhodes’s” probably refers to both of them going, and has been included as an entry under both Kipling, Caroline, and Kipling, Rudyard. There are many other similar events. And there are entries recording that, e.g., “Mrs. Kipling leaves”, without any indication of when she had come – but if it’s not in the ‘Extracts’ (though it may well have been in the original diaries) then, of course, it has not been possible to index it. The date given is the date of the diary entry which is not always the date of the event. We would also emphasise that the index does not necessarily give a complete record of who the Kiplings met, where they met them and what they did. It’s only an index of what remains of Carrie’s diaries, as recorded by Carrington and Rees. (We know a lot more about those people, places and things from, for example, Kipling’s published correspondence – but if they’re not in the diary extracts, then they won’t be found in this index.) Another factor is that both Carrington and Rees quite often mentions a name without further explanation or identification. -

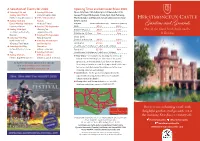

Gardens and Grounds

A Selection of Events for 2020 Opening Times and Admission Prices 2020 u Saturday 21st and u Sunday 28th June Open daily from 15th February to 1st November 2020 Sunday 22nd March Canadian Connections (except Friday 28th August), 10am–6pm (5pm February, Mother’s Day Afternoon Tea u 29th, 30th and 31st March, October and November). Last admission one hour u Sunday 12th and August before closing. Easter Monday 13th April Medieval Festival Daily Rate Gardens and Grounds only Castle Tours (extra fee) Gardens and Grounds Easter Family Fun u Sunday 13th September Adult £7.00 £3.00 u Sunday 26th April Wedding Fair Child (4–17 years) £3.50 £1.50 One of the finest brick built castles Tea Dance in the Castle (Empirical Events) Child (under 4), Carer Free Free in Britain Ballroom u Sunday 27th September u Saturday 16th May Taste of Autumn Senior (65+), Castle Night Trek u Saturday 31st October Disabled and Student £6.00 £3.00 (Chestnut Tree House) and Sunday 1st Family of 4 £17.50 N/A u Saturday 23rd May November (2 adults and 2 children or 1 adult and 3 children) National Garden Scheme Halloween Horrors Family of 5 £21.50 N/A Day u Sundays 13th and (2 adults and 3 children or 1 adult and 4 children) u Sunday 21st June 20th December u Tour times – are available by checking the website or Father’s Day Afternoon Tea Christmas Lunch and Carols calling 01323 833816 (please note that as the Castle operates as an International Study Centre for Queen’s For further information and full events calendar University in Canada, it is not freely open to the public and visit www.herstmonceux-castle.com tours are scheduled around timetables and other uses or email [email protected] including conferences/weddings). -

Elizabethan Diplomatic Networks and the Spread of News

chapter 13 Elizabethan Diplomatic Networks and the Spread of News Tracey A. Sowerby Sir Thomas Smith, Elizabeth I’s ambassador in France, wrote to her longest serving secretary, Sir William Cecil, in 1563 that “yf ye did understand and feele the peyne that Ambassadoures be in when thei can have no aunswer to ther lettres nor intilligence from ther prince, nor hir cownsell, ye wold pitie them I assure yow”. This pain was particularly acute, Smith went on to explain, when there were worrying rumours, such as those circulating at the French court that Queen Elizabeth was dead or very ill.1 Smith was far from the only Elizabethan ambassador to highlight the importance of regular news from home. Almost every resident ambassador Elizabeth sent abroad did so at some point during his mission. Practical and financial considerations meant that English ambassadors often had to wait longer than was desirable for domestic news; it was not unusual for ambassadors to go for one or two months without any news from the Queen or her Privy Council. For logistical reasons diplomats posted at courts relatively close to London were more likely to receive more regular information from court than those in more distant courts such as those of the Spanish king or Ottoman Emperor, or who were attached to semi- peripatetic courts. There were financial reasons too: sending a special post from Paris to London and back cost at least £20 in 1566.2 But sending news through estab- lished postal routes or with other ambassadors’ packets, while considerably cheaper, was also much less secure and took longer.3 A lack of news could hinder a diplomat’s ability to operate effectively. -

London and South East

London and South East nationaltrust.org.uk/groups 69 Previous page: Polesden Lacey, Surrey Pictured, this page: Ham House and Garden, Surrey; Basildon Park, Berkshire; kitchen circa 1905 at Polesden Lacey Opposite page: Chartwell, Kent; Petworth House and Park, West Sussex; Osterley Park and House, London From London living at New for 2017 Perfect for groups Top three tours Ham House on the banks Knole Polesden Lacey The Petworth experience of the River Thames Much has changed at Knole with One of the National Trust’s jewels Petworth House see page 108 to sweeping classical the opening of the new Brewhouse in the South East, Polesden Lacey has landscapes at Stowe, Café and shop, a restored formal gardens and an Edwardian rose Gatehouse Tower and the new garden. Formerly a walled kitchen elegant decay at Knole Conservation Studio. Some garden, its soft pastel-coloured roses The Churchills at Chartwell Nymans and Churchill at restored show rooms will reopen; are a particular highlight, and at their Chartwell see page 80 Chartwell – this region several others will be closed as the best in June. There are changing, themed restoration work continues. exhibits in the house throughout the year. offers year-round interest Your way from glorious gardens Polesden Lacey Nearby places to add to your visit are Basildon Park see page 75 to special walks. An intriguing story unfolds about Hatchlands Park and Box Hill. the life of Mrs Greville – her royal connections, her jet-set lifestyle and the lives of her servants who kept the Itinerary ideas house running like clockwork. -

![Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5807/complete-baronetage-of-1720-to-which-erroneous-statement-brydges-adds-845807.webp)

Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds

cs CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 092 524 374 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924092524374 : Complete JSaronetage. EDITED BY Gr. Xtl. C O- 1^ <»- lA Vi «_ VOLUME I. 1611—1625. EXETER WILLIAM POLLAKD & Co. Ltd., 39 & 40, NORTH STREET. 1900. Vo v2) / .|vt POirARD I S COMPANY^ CONTENTS. FACES. Preface ... ... ... v-xii List of Printed Baronetages, previous to 1900 xiii-xv Abbreviations used in this work ... xvi Account of the grantees and succeeding HOLDERS of THE BARONETCIES OF ENGLAND, CREATED (1611-25) BY JaMES I ... 1-222 Account of the grantees and succeeding holders of the baronetcies of ireland, created (1619-25) by James I ... 223-259 Corrigenda et Addenda ... ... 261-262 Alphabetical Index, shewing the surname and description of each grantee, as above (1611-25), and the surname of each of his successors (being Commoners) in the dignity ... ... 263-271 Prospectus of the work ... ... 272 PREFACE. This work is intended to set forth the entire Baronetage, giving a short account of all holders of the dignity, as also of their wives, with (as far as can be ascertained) the name and description of the parents of both parties. It is arranged on the same principle as The Complete Peerage (eight vols., 8vo., 1884-98), by the same Editor, save that the more convenient form of an alphabetical arrangement has, in this case, had to be abandoned for a chronological one; the former being practically impossible in treating of a dignity in which every holder may (and very many actually do) bear a different name from the grantee. -

And Humanist Learning in Tudor England a Thesis

ROGER ASCHAM AND HUMANIST LEARNING IN TUDOR ENGLAND by HARRAL E. LANDRY,, A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the Graduate School of the University of Alabama UNIVERSITY, ALABAMA 1958 PREFACE Roger Ascham was probably the greatest teacher in Elizabethan England. The period is graced with the name of his most famous and most spectacular pupil - Elizabeth Tu.dor. His life was dedicated, if indeed to anything, to the Greek ideal of "a sound mind in a sound body •." In addition, he reached a zenith as probably the greatest Latin letter writer in England. This achievement is all the more remarkable since his era was one of scholarship in the language of ancient Latium and of Rome. Yet, he is without a biographer, except in short sketches prefacing the editions of his writings. The purpose of this thesis is to collect some of the thoroughly scattered material and look a little more close ly at Ascham as a student, scholar, and particularly as a teacher. Every effort has been made to work with source material. Old English spellings have been modernized to provide continuity, uniformity, and smoothness of reading. Exceptions will be found in original book titles. Making a study of ideas is like steering a tricky passage between the perils of Scylla and Charybdis. In narrow straits the channel is often both,deep and indeter minate. The navigation of such a passage, even on my unlearned and far from comprehensive level, would have been impossible were it not for the generous assistance of a number of people. -

Thomas Philipott, Villare Cantianum, 2Nd Ed. (King's Lynn, 1776)

Thomas Philipott Villare Cantianum, 2nd edition King’s Lynn 1776 <1> VILLARE CANTIANUM: OR KENT Surveyed and Illustrated. KENT, in Latin Cantium, hath its derivation from Cant, which imports a piece of land thrust into a nook or angle; and certainly the situation hath an aspect upon the name, and makes its etymology authentic. It is divided into five Laths, viz. St. Augustins, Shepway, Scray, Alresford, and Sutton at Hone; and these again are subdivided into their several bailywicks; as namely, St. AUGUSTINS comprehends BREDGE, which contains these Hundreds: 1 Ringesloe 2 Blengate 3 Whitstaple 4 West-gate 5 Downhamford 6 Preston 7 Bredge and Petham 8 Kinghamford and EASTRY, which con= tains these: 1 Wingham 2 Eastry 3 Corniloe 4 Bewesborough SHEPWAY is divided into STOWTING, and that into these hundreds: 1 Folkstone 2 Lovingberg 3 Stowting 4 Heane and SHEPWAY into these: 1 Bircholt Franchise 2 Streat 3 Worth 4 Newchurch 5 Ham 6 Langport 7 St. Martins 8 Aloes Bridge 9 Oxney SCRAY is distinguished into MILTON. comprehends 1 Milton 2 Tenham SCRAY. 1 Feversham 2 Bocton under Blean 3 Felborough CHART and LONGBRIDGE. 1 Wye 2 Birch-Holt Ba= rony 3 Chart and Long-bridge 4 Cale-hill SEVEN HUN= DREDS. 1 Blackbourne 2 Tenderden 3 Barkley 4 Cranbrook 5 Rolvenden 6 Selbrightenden 7 Great Bern= field ALRESFORD is resolved into EYHORN is divided into 1 Eyhorn 2 Maidstone 3 Gillingham and 4 Chetham HOO 1 Hoo 2 Shamell 3 Toltingtrough 4 Larkfield 5 Wrotham and TWYFORD. 1 Twyford 2 Littlefield 3 Lowy of Tun= bridge 4 Brenchly and Hormonden 5 Marden 6 Little Bern= field 7 Wallingston 2 SUTTON at Hone, does only comprehend the bailywick of Sutton at Hone, and that lays claim to these hundreds.