Shifting Infrastructures 367

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Community Needs and Resources Assessment for the Port Aux Basques and Burgeo Areas

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN ACTION A Community Needs and Resources Assessment for the Port aux Basques and Burgeo Areas 2013 Prepared by: Danielle Shea, RD, M.Ad.Ed. Primary Health Care Manager, Bay St. George Area Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 4 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Page 6 Survey Overview Page 6 Survey Results Page 7 Demographics Page 7 Community Services Page 8 Health Related Community Services Page 10 Community Groups Page 15 Community Concerns Page 16 Other Page 20 Focus Group Overview Page 20 Port aux Basques: Cancer Care Page 21 Highlights Page 22 Burgeo: Healthy Eating Page 23 Highlights Page 24 Port aux Basques and Burgeo Areas Overview Page 26 Statistical Data Overview Page 28 Statistical Data Page 28 Community Resource Listing Overview Page 38 Port aux Basques Community Resource Listing Page 38 Burgeo Community Resource Listing Page 44 Strengths Page 50 Recommendations Page 51 Conclusion Page 52 References Page 54 Appendix A Page 55 Primary Health Care Model Appendix B Page 57 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Policy Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Port aux Basques/ Burgeo Area Page 2 Appendix C Page 62 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Survey Appendix D Page 70 Port aux Basques Focus Group Questions Appendix E Page 72 Burgeo Focus Group Questions Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Port aux Basques/ Burgeo Area Page 3 Executive Summary Primary health care is defined as an individual’s first contact with the health system and includes the full range of services from health promotion, diagnosis, and treatment to chronic disease management. -

NEWFOUNDLAND RAILWAY the OVERLAND ROUTE Ready and Anxious to Serve Your .)/; .)/; .)/; .)/; Every Transportation Requirement

THE l'E\HOU:-IDLA:-;n QL'ARTERLY. _ PKf~lm 'T-Iluntley H.. 01 Jmm mel. Gic .... ERAI. MA.... ACa;R~ (;. \\'. Spinllc\ Caplt.al Paid up $36,000,000.00 Rest. and Undivided Profit.s 39,000,000.00 Tot.al Asset.s-In Excess of 950,000,000.00 , Fiscal Agents in London for the Dominion of Canada..$ .,¢ .$ .$ Bankers for the Government of Newfoundland. Lond.. u,laad, Bruc.hu--47 ThnadDeedle Stred., and 9 Watertoo Piace. BnDeMs in New York, QUaro, San Frucilce, aDd enry ProriDce of tile Dominion of Cuada. Newfolllldlaad-Cnrliog, Coraer Brook, Crud Fall., St. Georre',. aDd Bach... (Sob-Arency). St.. John's-C. D. HART, Manager. D. O. ATKINSON, Asst. Manager. Commercial Letters of Credit, and Tr.l\"cllt,r.-,' Lettcr~ of Credit issued available ill all parts of the world. Special altetllioa ,ifel 10 Sarin,. Ace"DI••Dit. may lie opeJled by ckposib of $1.00 aDd UPWDr" BOWRING BROTUERS, Ltd ST. JO"N'S, NEWFOUNDLAND - Established 1811 - GENERAL MERCHANTS and STEAMSHIP OWNERS \\'hole'q!e and Retail Dealers in Dry Goods, Hardware, Groceries and Ships' Stores Expurter,., {If Codfish, Codoil, Cod Liver Oil, Seal Oil and Seal Skins A,"lI for .. UOyd·... and Unrpool aDd LondoD aDd Clobe r.....uc:e Company IroD or Wooden Sew, SlUp. suitable for Arctic or Antarctic nplol1ltion aniiable for narter Sport<;men '.1110 intend \isiting Newfoundland will find no difficulty in selecting Gun!!. Ammunition, Fishing Tackle and Food Supplies from this firm. Add",••11 ~.m~"H'" BOWRING BROTHERS, Ltd., 51. J~~:;~UDdl ..d. THE NEWFOUNDLAND QUARTERLY.-I. -

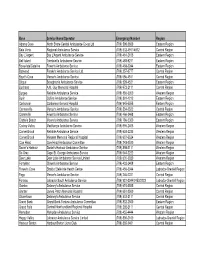

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Burgeo Lifeboat Station

Burgeo Lifeboat Station AS-BUILT DRAWING AS-BUILT DRAWING Goose Bay Marine Communications and Traffic Service (MCTS) Centre Lark Harbour Lifeboat Station AS-BUILT DRAWING AS-BUILT DRAWING Previous Port Aux Basques Marine Communications and Traffic Service (MCTS) Centre Port Aux Basques Marine Communications and Traffic Service (MCTS) Centre Port Au Choix Lifeboat Station St. Anthony Lifeboat Station St. Lewis Conservation and Protection Office Stephenville Base Twillingate Lifeboat Station C 1 2 3 4 5.1 5 4.1 6 7 8 Public Works and Travaux Publics et Government Services Services gouvernementaux Canada Canada A A BERTOIA HS TS VESTIBULE GEAR AND DRYING VESTIBULE 115 114 101 HP -005 B B RG RL LIVING/RECREATION RECYCLING OPS WR TS 112 111 110 ELECTRICAL OPS ROOM CO2 109 103 CORRIDOR 6 102 12 HP -003 12 6 TS CO2 HP -006 RG RG RG RL RL RL 2018.07.18 10 MECHANICAL 10 6 TS CO2 16 107 16 12 HP -002 HP -001 10 HP -004 20 KITCHEN RL FITNESS DDC PANEL STAIR OPS STOR ENGINEER CO OFFICE 117 RG 108 S01 106 105 104 16mm REFRIGERANT GAS AND 10mm TS TS REFRIGERANT LIQUID UP TO LEVEL 2 C C CU -001 CU -002 FOR DETAILED REFRIGERANT LINE SIZING 1 2 3 4 5.1 5 4.1 6 7 8 INFORMATION SEE HEAT PUMP SCHEMATICS DRAWING H601. 1 HEATING AND A/C PLAN - LEVEL 1 H104 SCALE 1 : 75 C 1 2 3 4 5.1 5 4.1 6 7 8 A A B B 0 ISSUED FOR TENDER 2018.07. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 84 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2009 No. 43 EMBALMERS AND FUNERAL DIRECTORS ACT, 2008 NOTICE The following is a list of names and addresses of Funeral Homes 2009 to whom licences and permits have been issued under the Embalmers and Funeral Directors Act, cE-7.1, SNL2008 as amended. Name Street 1 City Province Postal Code Barrett's Funeral Home Mt. Pearl 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Barrett's Funeral Home St. John's 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Blundon's Funeral Home-Clarenville 8 Harbour Drive Clarenville NL A5A 4H6 Botwood Funeral Home 147 Commonwealth Drive Botwood NL A0H 1E0 Broughton's Funeral Home P. O. Box 14 Brigus NL A0A 1K0 Burin Funeral Home 2 Wilson Avenue Clarenville NL A5A 2B6 Carnell's Funeral Home Ltd. P. O. Box 8567 St. John's NL A1B 3P2 Caul's Funeral Home St. John's P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Caul's Funeral Home Torbay P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Central Funeral Home--B. Falls 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--GF/Windsor 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--Springdale 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Conway's Funeral Home P. O. Box 309 Holyrood NL A0A 2R0 Coomb's Funeral Home P. O. Box 267 Placentia NL A0B 2Y0 Country Haven Funeral Home 167 Country Road Corner Brook NL A2H 4M5 Don Gibbons Ltd. -

January 2007

Volume XXV111 Number 1 January 2007 IN THIS ISSUE... VON Nurses Helping the Public Stay on Their Feet Province Introduces New Telecare Service New School Food Guidelines Sweeping the Nation Tattoos for You? Trust Awards $55,000 ARNNL www.arnnl.nf.ca Staff Executive Director Jeanette Andrews 753-6173 [email protected] Director of Regulatory Heather Hawkins 753-6181 Services [email protected] Nursing Consultant - Pegi Earle 753-6198 Health Policy & [email protected] - Council Communications Pat Pilgrim, President 2006-2008 Nursing Consultant - Colleen Kelly 753-0124 Jim Feltham, President-Elect 2006-2008 Education [email protected] Ann Shears, Public Representative 2004-2006 Nursing Consultant - Betty Lundrigan 753-6174 Ray Frew, Public Representative 2004-2006 Advanced Practice & [email protected] Kathy Watkins, St. John's Region 2006-2009 Administration Kathy Elson, Labrador Region 2005-2008 Nursing Consultant - Lynn Power 753-6193 Janice Young, Western Region 2006-2009 Practice [email protected] Bev White, Central Region 2005-2008 Project Consultant JoAnna Bennett 753-6019 Ann Marie Slaney, Eastern Region 2004-2007 QPPE (part-time) [email protected] Cindy Parrill, Northern Region 2004-2007 Accountant & Office Elizabeth Dewling 753-6197 Peggy O'Brien-Connors, Advanced Practice 2006-2009 Manager [email protected] Kathy Fitzgerald, Practice 2006-2009 Margo Cashin, Practice 2006-2007 Secretary to Executive Christine Fitzgerald 753-6183 Director and Council [email protected] Catherine Stratton, Nursing Education/Research -

Executive Notes, May 8, 2015 from the NLTA

Newfoundland and Labrador Teachers’ Association EXECUTIVE NOTES May 8, 2015 our NLTA Provincial Executive met in St. John’s rebuild and recover from the earthquake devastation. Yon May 8, 2015. Executive Notes is a summary of • The NLTA will provide $500 to the NL Federation of discussions and decisions that occurred at these meetings. School Councils to assist with their AGM. For further information contact any member of Provincial • The NLTA will sponsor St. John’s Pride to the level of Executive or the NLTA staff person as indicated. $1,000 (silver sponsorship) pending a review of the promotional material for St. John’s Pride 2015. President’s Report Since the February meeting of Provincial Executive the For further information contact James Dinn, President President has attended numerous functions and visited or Don Ash, Executive Director. schools in St. John’s, Paradise, Conne River, Milltown, Ad Hoc Committee on Substitute Teachers English Harbour West, Harbour Breton, Lewisporte, • The NLTA will lobby the districts and the Department of Campbellton and Norris Arm. He presented NLTA’s pre- Education and Early Childhood Development to increase budget consultation brief to the Minister of Finance, met substitute teachers’ access to professional development with NLESD Trustees, met with the Minister of Finance sessions. regarding pension discussions, and with the Minister of • The NLTA will consider offering professional Education and Early Childhood Development regarding development sessions specifically for substitutes, as teacher allocation cuts. He attended the 2015 International well as consider the most viable way to offer these Summit on the Teaching Profession, the substitute teacher sessions to as many substitute teachers as possible. -

Hearing Aid Providers (Including Audiologists)

Hearing Aid Providers (including Audiologists) Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 16 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2R6 1-709-489-8500 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-489-8497 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioners: Joanne Hunter, Jodine Reid Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 3 Herald Avenue Corner Brook, NL A2H 4B8 1-709-639-8501 (Corner Brook) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-639-8502 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioner: Jason Gedge Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Hearing Service 3 Paton Street St. John’s, NL A1B 4S8 1-709-726-8083 (St. John’s) 1-800-563-8083 (Toll free) 1-709-726-8111 (Fax) [email protected] www.beltone.nl.ca Audiologists: Brittany Green Hearing Aid Practitioners: Mike Edwards, David King, Kim King, Joe Lynch, Lori Mercer Satellite Locations: Bay Roberts, Bonavista, Carbonear, Clarenville, Gander, Grand Bank, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador City, Lewisporte, Marystown, New-Wes- Valley, Twillingate ________________________________ Exploits Hearing Aid Centre 9 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2S8 1-709-489-8900 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-800-563-8901 (Toll free) 1-709-489-9006 (Fax) [email protected] www.exploitshearing.ca Hearing Aid Practitioners: Dianne Earle, William Earle, Toby Penney ________________________________ Maico Hearing Service 84 Thorburn Road St. -

Student and Youth Services Agreement.Xlsx

2015-16 Student and Youth Services Agreement Approvals Organization Location Project Approved Amount BOTWOOD BOYS AND GIRLS CLUB Botwood Youth Cordinator$ 40,100 CBDC TRINITY CONCEPTION CORPORATION Carbonear Community Youth Coordinator$ 87,500 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 229,714 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 90,155 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 57,232 (PACEE) COMMUNITY YOUTH NETWORK CORNER BROOK & AREA Corner Brook Impact $ 5,071 CONSERVATION CORPS NEWFOUNDLAND AND St. John's Green Team$ 579,600 LABRADOR FOR THE LOVE OF LEARNING, INC St. John's Watering the Seeds$ 115,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Entreprensurial Skills$ 35,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Outreach Coordinator$ 52,500 HARBOUR GRACE COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Grace Changing Lanes$ 60,301 KANGIDLUASUK STUDENT PROGRAM INC Nain Student Program$ 7,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Youth Opportinities Coop Program$ 100,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Wage Subsidies for MESD$ 11,186 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 522,993 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Graduate Transition to Employment (GTEP)$ 200,000 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 331,680 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 67,732 (PACEE) NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ASSOC OF Mount Pearl Youth Ventures$ 82,000 COMMUNITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT CORPORATIONS SKILLS CANADA-NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR St. -

Labrador Shelves Bioregion

Incorporating Representativity into Marine Protected Area Network Design in the Newfoundland- Labrador Shelves Bioregion Ecosystems Management Publication Series Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0010 2014 Incorporating Representativity into Marine Protected Area Network Design in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelves Bioregion by Laura E. Park1 and Francine Mercier2 Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P. O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region, P.O. Box 5667, St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 2 Parks Canada, 25 Eddy St., 4th floor, Gatineau, QC, K1A 0M5 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014 Cat. No. Fs22-10/10-2014E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-14003-2 978-1-100-25363-3 DFO No. 2014-1939 Correct citation for this publication: Park, L. E. and Mercier F. 2014. Incorporating Representativity into Marine Protected Area Network Design in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelves Bioregion. Ecosystems Management Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region. 0010: vi + 31 p. ii Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Environment Canada and the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture in reviewing the various drafts of this document as it evolved. Particular thanks go to Karel Allard and Bobbi Rees for their valuable input. iii iv TABLE of CONTENTS ABSTRACT/RÉSUMÉ ................................................................................................................ vii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 -

Physical Oceanographic Conditions on the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelf During 2016

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2017/079 Newfoundland and Labrador Region Physical Oceanographic Conditions on the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelf during 2016 E. Colbourne, J. Holden, S. Snook, G. Han, S. Lewis, D. Senciall, W. Bailey, J. Higdon and N. Chen Science Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada PO Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 November 2017 (Errata: February 2018) Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2017 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Colbourne, E., Holden, J., Snook, S., Han, G., Lewis, S., Senciall, D., Bailey, W., Higdon, J., and Chen, N. 2017. Physical oceanographic conditions on the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelf during 2016 - Erratum. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2017/079. v + 50 p. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... IV RÉSUMÉ -

Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-20 to 30-Sep-20

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-20 to 30-Sep-20 LOVELESS, ELVIS, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2020/21 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $7,800.00 Transactions Processed as of: 30-Sep-20 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $5,850.00 Funds Available (Net of HST): $1,950.00 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 75.0% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 01-Apr-20 HOA006183 ROY DRAKE Lease payment for the Constituency Office for the District of Fortune Bay - Cape 975.00 La Hune located in Harbour Breton. 01-May-20 HOA006216 ROY DRAKE Lease payment for the Constituency Office for the District of Fortune Bay - Cape 975.00 La Hune located in Harbour Breton. 01-Jun-20 HOA006252 ROY DRAKE Lease payment for the Constituency Office for the District of Fortune Bay - Cape 975.00 La Hune located in Harbour Breton. 01-Jul-20 HOA006295 ROY DRAKE Lease payment for the Constituency Office for the District of Fortune Bay - Cape 975.00 La Hune located in Harbour Breton. 01-Aug-20 HOA006334 ROY DRAKE Lease payment for the Constituency Office for the District of Fortune Bay - Cape 975.00 La Hune located in Harbour Breton. 01-Sep-20 HOA006370 ROY DRAKE Lease payment for the Constituency Office for the District of Fortune Bay - Cape 975.00 La Hune located in Harbour Breton. Period Activity: 5,850.00 Opening Balance: 0.00 Ending Balance: 5,850.00 ---- End of Report ---- House of Assembly