Southlight 28 Master Corrected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elenco Film Dal 2015 Al 2020

7 Minuti Regia: Michele Placido Cast: Cristiana Capotondi, Violante Placido, Ambra Angiolini, Ottavia Piccolo Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Koch Media Srl Uscita: 03 novembre 2016 7 Sconosciuti Al El Royale Regia: Drew Goddard Cast: Chris Hemsworth, Dakota Johnson, Jeff Bridges, Nick Offerman, Cailee Spaeny Genere: Thriller Distributore: 20th Century Fox Uscita: 25 ottobre 2018 7 Uomini A Mollo Regia: Gilles Lellouche Cast: Mathieu Amalric, Guillaume Canet, Benoît Poelvoorde, Jean-hugues Anglade Genere: Commedia Distributore: Eagle Pictures Uscita: 20 dicembre 2018 '71 Regia: Yann Demange Cast: Jack O'connell, Sam Reid Genere: Thriller Distributore: Good Films Srl Uscita: 09 luglio 2015 77 Giorni Regia: Hantang Zhao Cast: Hantang Zhao, Yiyan Jiang Genere: Avventura Distributore: Mescalito Uscita: 15 maggio 2018 87 Ore Regia: Costanza Quatriglio Genere: Documentario Distributore: Cineama Uscita: 19 novembre 2015 A Beautiful Day Regia: Lynne Ramsay Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Alessandro Nivola, Alex Manette, John Doman, Judith Roberts Genere: Thriller Distributore: Europictures Srl Uscita: 01 maggio 2018 A Bigger Splash Regia: Luca Guadagnino Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Dakota Johnson Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Lucky Red Uscita: 26 novembre 2015 3 Generations - Una Famiglia Quasi Perfetta Regia: Gaby Dellal Cast: Elle Fanning, Naomi Watts, Susan Sarandon, Tate Donovan, Maria Dizzia Genere: Commedia Distributore: Videa S.p.a. Uscita: 24 novembre 2016 40 Sono I Nuovi 20 Regia: Hallie Meyers-shyer Cast: Reese Witherspoon, Michael Sheen, Candice -

Hellstorm, the Death of Nazi Germany

00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page i hellstorm 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page ii 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page iii hellstorm The Death of Nazi Germany 1944–1947 by Thomas Goodrich ABERDEEN BOOKS Sheridan, Colorado 2010 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page iv Hellstorm: The Death of Nazi Germany, 1944‒1947 By Thomas Goodrich First printing, 2010 Aberdeen Books 3890 South Federal Boulevard Sheridan, Colorado 80110 303-795-1890 [email protected] · www.aberdeenbookstore.com isbn 978-0-9713852-2-11494775069 © 2010 Aberdeen Books All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Design by Ariane C. Smith Capital A Publications, llc Spokane, Washington 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page v To the voiceless victims of the world’s worst war 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page vi 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page vii Table of Contents Prologue 1 1 Hell from Above 13 2 The Dead and the Dead to Be 43 3 Between Fire and Ice 69 4 Crescendo of Destruction 95 5 The Devil’s Laughter 129 6 The Last Bullet 161 7 A Sea of Blood 185 8 Unspeakable 225 9 A War without End 277 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page viii 10 The Halls of Hell 299 11 Crime of the Age 325 Epilogue: Of Victors and Victims 347 Bibliography 361 Index 367 00-FM pgd 3/27/10 4:18 PM Page ix Illustrations Ilya Ehrenburg 261 Hamburg 261 After the Fire Storm 262 Arthur Harris 262 The “Good War” 263 The Wilhelm Gustloff 264 Yalta: Winston -

Korn Albums Download

Korn albums download click here to download Banda: Korn. Gênero: Nu Metal, Metal Alternativo. Período em Atividade: - Atualmente. Integrantes: Jonathan Davis, James "Munky". 28 abr. Korn (às vezes escrito como KoRn ou KoЯn, para imitar o símbolo da banda) é uma banda de metal alternativo de Bakersfield, Califórnia, que .. Como Baixar / How To Download. .. Falling Away From Me (Album Version). Korn [stylized as "KoЯn"] is a Grammy Award winning Metal band from Bakersfield, . Korn - Korn album art Korn - Take A Look In The Mirror album art. Find Korn discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. Korn's cathartic alternative metal sound positioned the group among the most popular and Essential Albums Korn - See You on the Other Side (Songbook) . Korn - Korn - www.doorway.ru Music. Korn - Follow The Leader Audio CD. Korn .. David Silveria's drumming is the best of all KoRn's albums by far, he pounds the $hit out of the drums with great style and incredible fills all the way . Download. KORN (FREE DOWNLOAD) FULL ALBUM Studio Albums Korn () Life Is Peachy () Follow the Leader () Issues (). Listen to music from Korn like Freak on a Leash, Falling Away From Me & more. Find the latest tracks, albums, and images from Korn. Released: October 15, (US); Label: Immortal, Epic; Formats: CD, cassette, LP, digital download. 3, 26, 21, 32, 24, 85, 87, 1. Jonathan Davis on the new Korn album, his solo record, trap metal and You brought your solo project over to Download earlier this year. Korn (printed as KoЯn) is the debut studio album by American nu metal band Korn. -

Preacher's Magazine Volume 04 Number 03 J

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Preacher's Magazine Church of the Nazarene 3-1929 Preacher's Magazine Volume 04 Number 03 J. B. Chapman (Editor) Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, J. B. (Editor), "Preacher's Magazine Volume 04 Number 03" (1929). Preacher's Magazine. 45. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm/45 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Church of the Nazarene at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Preacher's Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Preacher’s Magazine A monthly journal devoted to the interests of those who preach the full gospel J. B. Chapman, Editor Published monthly by the Nazarene Publishing House, 2923 Troosi Ave., Kansas City, Mo., maintained by and in the interest of the Church of the Nazarene. Subscription price $1.00 per year. Entered as second class matter at the Postoffice at Kansas City, Mo. Acceptance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in Section 1103, Act of October 3, 1917, authorized December 30, 1925. V o l u m e 4 March, 1929 N u m b e r 3 ON PASTORAL VISITING LL EFFORTS to divorce the preacher and the pastor have failed. The man who preaches to the people is the man to visit in their homes, for each phase of the work is the counterpart of the other. -

The Lone Wolf0 a Melodrama Louis Joseph Vance

The Lone Wolf0 A Melodrama Louis Joseph Vance The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Lone Wolf, by Louis Joseph Vance #2 in our series by Louis Joseph Vance Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Lone Wolf A Melodrama Author: Louis Joseph Vance Release Date: November, 2005 [EBook #9378] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on September 26, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LONE WOLF *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Jayam Subramanian and PG Distributed Proofreaders THE LONE WOLF By LOUIS JOSEPH VANCE 1914 CONTENTS I. TROYON'S II. RETURN III. A POINT OF INTERROGATION IV. A STRATAGEM V. ANTICLIMAX VI. THE PACK GIVES TONGUE VII. -

Arthur Morrison, the 'Jago', and the Realist

ARTHUR MORRISON, THE ‘JAGO’, AND THE REALIST REPRESENTATION OF PLACE Submitted in Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy UCL Department of English Language and Literature Eliza Cubitt 2015 ABSTRACT In vitriolic exchanges with the critic H.D. Traill, Arthur Morrison (1863-1945) argued that the term ‘realist’ was impossible to define and must be innately subjective. Traill asserted that Morrison’s A Child of the Jago (1896) was a failure of realism, conjuring a place that ‘never did and never could exist.’ And yet, by 1900, the East End slum fictionalised in Morrison’s novel had been supplanted by the realist mythology of his account: ‘Jago’ had become, and remains, an accepted term to describe the real historical slum, the Nichol. This thesis examines Morrison’s contribution to the late-Victorian realist representation of the urban place. It responds to recent renewed interest about realism in literary studies, and to revived debates surrounding marginal writers of urban literature. Opening with a biographical study, I investigate Morrison’s fraught but intimate lifelong relationship with the East End. Morrison’s unadorned prose represents the late-Victorian East End as a site of absolute ordinariness rather than absolute poverty. Eschewing the views of outsiders, Morrison re- placed the East End. Since the formation of The Arthur Morrison Society in 2007, Morrison has increasingly been the subject of critical examination. Studies have so frequently focused on evaluating the reality behind Morrison’s fiction that his significance to late-nineteenth century “New Realism” and the debates surrounding it has been overlooked. This thesis redresses this gap, and states that Morrison’s work signifies an artistic and temporal boundary of realism. -

Growing in Goodness Towards a Symbiotic Ethics

1 Growing in Goodness Towards a Symbiotic Ethics Submitted by Alexander Badman-King, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in philosophy; 12/2016 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without prop- er acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been iden- tified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) Alexander Badman-King 1 2 ABSTRACT At its core, this thesis represents an attempt to outline and clarify a concept of ‘wis- dom’. Building upon a fairly well established tradition of ‘philosophy as a way of life’ the discussion sets out an understanding of a model of philosophy which sets a un- ion of the virtues as its ultimate goal (finding models of non-ethical and primarily ac- ademic philosophy to be lacking). Aristotle’s practical wisdom and Plato’s humble, human wisdom are found to be complimentary in certain key respects and useful (in conjunction) in describing the nature of this ‘wisdom’ as a state of moral expertise and broad insight (an understanding of, and action according to, that which is most important). An account is given of the kind of moderate moral realism which is able to account for the ‘moral facts’ which are necessary to render this sort of moral knowledge viable. This moderate realism is founded upon a similarly moderate or compromising epistemology which will itself constitute a recurring theme of this ‘wis- dom’. -

Loudwire.Com/Ozzy-Osbourne-Rob-Zombie-Ozzfest-2018-Photos- Recap/ A

JANUARY 1, 2019 Link to article: https://loudwire.com/ozzy-osbourne-rob-zombie-ozzfest-2018-photos- recap/ A Courtesy of MSO Ozzfest has taken many forms over the years, but on Dec. 31, 2018 it served as a way send out 2018 with a major location-based event and ring in 2019 with some of rock and metal's finest throwing a bash to remember. Ozzy Osbourne, who months earlier had to postpone a Los Angeles concert due to health issues, returned to the concert stage at the Forum full of energy and ready to count down the final minutes of the year. But before that, a stellar lineup rocked fans inside and outdoors at the Forum during a brisk but sunny afternoon. Wednesday 13 kicked off the festivities at 2:30PM, with a crew member getting in the spirit by shooting fake snow into the crowd. Their high energy set gave way to a more crushing performance from Dez Fafara and his DevilDriver crew. The moshpits started to form in the Forum parking lot as Fafara rallied the audience into a frenzy. The singer and guitarist Mike Spreitzer also showed their appreciation hanging around to meet with fans and take photos following their set. As DevilDriver came to a close, the almighty Zakk Wylde rolled up on a golf cart, greeted fans and signed autographs as he made is way to the stage. Other than Osbourne of course, Wylde may very well have been on the most Ozzfests between playing with Ozzy and Black Label Society. Wylde, fresh off the "Generation Axe" tour, played an hour-long set with his tribute band Zakk Sabbath, riffing through classics like “Snowblind,” “Into the Void,” and “N.I.B.” With the sun starting to fade, it was time to move the show indoors for the remainder of the night. -

XCLUSIVE the Rise of Hip-Hop's Hottest Honey

whatson.guide Issue 331 New York 2018 Raye whatsOn Apps Angelina Jolie Download FREE YMCA +NY Special +WIN Prizes Cardi-O! XCLUSIVE The Rise of Hip-Hop’s Hottest Honey 100REASONS TO VISIT REASON NO.3: 100 YEARS OF RAF STORIES FREE ADMISSION rafmuseum.org Colindale 01 XCLUSIVEON 005 Agenda> NewsOn 007 Dispatch> Nugen 008 Fashion> NY 011 Report> 5 Ways 013 Interview> Raye 015 Report> Immigration 017 Xclusive> Cardi B 02 WHATSON 019 Action> Things To Do 020 Arts> Performance 023 Books> Q&A 025 Events> Festivals 027 Film> TV 029 Gigs> Clubs 031 Music> Releases 033 Sports> Games 03 GUIDEON 037 Best Picks> Briefing 053 Classified> Jobs JOAN SMALLS- 059 Ikon> GameOn RODRIGUEZ This tanned beauty from Puerto 063 SceneOn> Reviews Rico has been regarded as one of the New Supers in the 065 Take10> Challenge Trump fashion business. Joan has also made history, because in 066 WinOn> PlayOn 2011 she acquired the status of first Latina model to represent Estée Lauder cosmetics. Ads> T +44(0)121 655 1122 [email protected] Editorial> [email protected] About> whatsOn connects people with essential culture, events & news. Values> Diversity, Equality, Participation, Solidarity. Team WhatsOn>Managing Director Sam Alim Creative Director Setsu Adachi Assistant Editor Hannah Montgomery Editoral Assistants Juthy Saha, Shiuly Rina, Poushi Sarker Clubs Editor Nicole Lowe Features Naomi Round, Robert Elsmore Film Editor Mark Goddard Games Luke Allen Music Editor Gary Trueman Sports Bradley Montgomery TV Mar Martínez Graphic Designer Tarun Miah Asst Creative -

17 3Rd WORLD ELECTRIC (Feat. Roine Stolt)

24-7 SPYZ 6 – 8 3rd AND THE MORTAL Painting on glass - 17 3rd WORLD ELECTRIC (feat. Roine Stolt) Kilimanjaro secret brew digipack - 18 3RDEGREE Ones & zeros: volume I - 18 45 GRAVE Only the good die young – 18 46000 FIBRES )featuring Nik Turner) Site specific 2CD – 20 48 CAMERAS Me, my youth & a bass drum – 17 A KEW’S TAG Silence of the sirens - 20 A LIQUID LANDSCAPE Nightinagel express – 15 A LIQUID LANDSCAPE Nightingale express digipack – 17 A NEW’S TAG Solence of the sirens – 18 A SILVER MT ZION Destroy all dreamers on / Debt 6 depression digipack – 10 A SPIRALE Come una lastra – 8 AARDVARK (UK) Same - 17 ABACUS European stories (new album) – 17 ABDULLAH Graveyard poetry – 10 ABDULLAH Same – 10 ABIGAIL'S GHOST Black plastic sun - 18 ABRAXIS Same – 17 ABRETE GANDUL Enjambre sismico – 16 ABYSMAL GRIEF Feretri – 16 ABYSMAL GRIEF Reveal nothing - 16 ABYSMAL GRIEF Strange rites of evil – 16 AC/DC Let there be rock DVD Paris 1979 - 15 AC/DC Back in black digipack – 16 AC/DC Rock or bust – 21 AC/DC The razor’s edge digipack – 16 ACHE Green man / De homine urbano – 17 ACHIM REICHEL & MACHINES Echo & A. R. IV 2CD - 23 ACHIM REICHEL Grüne reise & Erholung - 17 ACID BATH Pagan terrorism tactics – 10 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE MELTING PARAISO U.F.O. Live in occident digipack – 17 ACINTYA La citè des dieux oublies – 18 ACQUA FRAGILE Mass media stars (Esoteric) - 18 ACQUA FRAGILE Same (Esoteric) – 18 ACTIVE HEED Higher dimensions – 18 ADEKAEM Same – 20 ADICTS Smart alex – 17 ADICTS Sound of music – 17 ADMIRAL SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVELL Don’t hear it…fear it (Rise Above) – 18 ADRIAN SHAW & ROD GOODWAY Oxygen thieves digipack – 15 ADRIAN SHAW Colours - 17 ADRIANO MONTEDURO E LA REALE ACCADEMIA DI MUSICA Same (Japanes edition) – 18 ADTVI La banda gastrica – 8 ADVENT Silent sentinel digisleeve – 18 AELIAN A tree under the colours – 8 AEONSGATE Pentalpha – 17 AEROSMITH Live and F.I.N.E. -

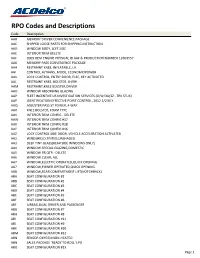

RPO Codes and Descriptions

RPO Codes and Descriptions Code Description AAB MEMORY DRIVER CONVENIENCE PACKAGE AAC SHIPPED LOOSE PARTS FOR SHIPPING INSTRUCTION AAD WINDOW BODY, LEFT SIDE AAE INTERIOR TRIM DELETE AAF 2009 OEM ENGINE PHYSICAL ID AAF & PRODUCTION NUMBER 12603557 AAG MEMORY PASS CONVENIENCE PACKAGE AAH RESTRAINT KNEE, INFLATABLE, LH AAI CONTROL A/TRANS, MODE, ECONOMY/POWER AAK LOCK CONTROL, ENTRY DOOR, ELEC, KEY ACTIVATED AAL RESTRAINT KNEE, BOLSTER, LH/RH AAM RESTRAINT,KNEE BOLSTER,DRIVER AAO WINDOW ABSORBING GLAZING AAP FLEET INCENTIVE US INVESTIGATION SERVICES (D/W/3A/3Z - TRK STUX) AAP IDENTIFICATION EFFECTIVE POINT CONTROL, 2012 1/2 M.Y. AAQ ADJUSTER PASS ST POWER, 4 WAY AAR KNEE BOLSTER, FOAM TYPE AAV INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG - DELETE AAW INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG #17 AAX INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG #18 AAY INTERIOR TRIM CONFIG #16 AAZ LOCK CONTROL SIDE DOOR, VEHICLE ACCELERATION ACTIVATED AA2 WINDSHIELD,TINTED,UNSHADED AA3 DEEP TINT GLASS(REAR SIDE WINDOWS ONLY) AA4 WINDOW SPECIAL GLAZING,DOMESTIC AA5 WINDOW RR QTR - DELETE AA6 WINDOW CLEAR, ALL AA7 WINDOW,ELECTRIC OPERATED,QUICK OPENING AA7 WINDOW,POWER OPERATED,QUICK OPENING AA8 WINDOW,REAR COMPARTMENT LIFT(NOTCHBACK) ABA SEAT CONFIGURATION #1 ABB SEAT CONFIGURATION #2 ABC SEAT CONFIGURATION #3 ABD SEAT CONFIGURATION #4 ABE SEAT CONFIGURATION #5 ABF SEAT CONFIGURATION #6 ABF AIRBAG,DUAL DRIVER AND PASSENGER ABG SEAT CONFIGURATION #7 ABH SEAT CONFIGURATION #8 ABI SEAT CONFIGURATION #11 ABJ SEAT CONFIGURATION #9 ABK SEAT CONFIGURATION #10 ABM SEAT CONFIGURATION #12 ABN SENSOR OXYGEN NON-HEATED ABN SALES PACKAGE -

The Union and Journal

NUMBER 27. VOLUME XXV. A MwUI her one* 1'nrtiml Cunoiitu from fliUlral TtJtit. Jf, />, IAnet* are wonderful 1 keep young still, no bit® of refreshment, Spare Itntitf foril .lftrrrti%r»unt%. The* p'rarrics roomy. thought but no no mt from thai fkt crow one I would let out entirely; exhjlanting draft, Ck clnion aiii Journal spell mywlf Cling la thr Might Onr, r». luiix, 19 I bad juat finiahed my iuf|*r, uxl win enjoy- How to make a clean inwp—waah him. aa cai#c to her all the save when mot her held a corcus, and decided that baby, long night, Id griff ( lltb xU, 11 u rctLi- Mu# it kit raiP4T »r iny Clio* thy cipir on the deck, when 1 hoard a man Mgpn««» lots for sale the man ami ing my A blanker baaa—kiaaing the wrong girt. "house was old an<l blind it took too big stretched out his hands Cling In the IN; Ooo, llrb. I. 13 she gi ttiup like, great in a load roleo, to two or three at- J. 12. BUTLEIl, II* relief. IV # declaiming, man—* taker. OXvT ST. too wv of took for an hour, and let him glrta exrl, An ill-bread tick POOL long and cost mncli to up the leg* the^btby play lixtcncn intet»l«| for Ktlitor » n «l Proprii'tor. Cling to th« (Iracioui Ow, !•». 4 tentive (but evidently O r i<* warn ire con- with his watch to him m*i are men a !*uujm- thy munourln; tinging trousers, and m> I a stop to it, and »plcn<lkl keep quiet.